Baroque (Italian barocco through the Spanish bar-ruecco from the Portuguese. Barroco - freaky, wrong, bad, spoiled) is one of the most difficult and meaningful terms of the history of art.  The word “baroque” refers to a number of historical and regional artistic styles of European art of the XVII-XVIII centuries, the last, critical stages of development of other styles, the tendency of a restless, romantic attitude, thinking in expressive, unbalanced forms.

The word “baroque” refers to a number of historical and regional artistic styles of European art of the XVII-XVIII centuries, the last, critical stages of development of other styles, the tendency of a restless, romantic attitude, thinking in expressive, unbalanced forms.

The word “baroque” is also used as a metaphor in bold historical and cultural generalizations: “Baroque epoch”, “Baroque world”, “Baroque man”, “Baroque life” (Italian: La vita Barocca).  In each historical period of the development of art, they see their own “baroque” - the peak of creative growth, concentration of emotions, tension of forms. Researchers talk and write about the qualities of Baroque as an inherent property of individual national cultures and historical types of art. Finally, the styles of Neo-Baroque, Second Baroque, Ultra Baroque are known. Initially, the slang term “baroque” was used by Portuguese sailors to denote irregular, distorted shapes of rejected gems.

In each historical period of the development of art, they see their own “baroque” - the peak of creative growth, concentration of emotions, tension of forms. Researchers talk and write about the qualities of Baroque as an inherent property of individual national cultures and historical types of art. Finally, the styles of Neo-Baroque, Second Baroque, Ultra Baroque are known. Initially, the slang term “baroque” was used by Portuguese sailors to denote irregular, distorted shapes of rejected gems.

But in the middle of the XVI century. This word appeared in colloquial Italian as a synonym for everything coarse, phony, clumsy.  Among French jewelers, the word baroquer means to soften the contour, to make the shape soft, picturesque. In French dictionaries, the word "baroque" appears since 1718 and is interpreted as an abusive expression. For a long time it could not become the name of the style. Back in 1904-1905. the largest French researcher S. Reinac does not seem to notice this style and an entire era in the development of European art, only casually and disparagingly recalling the “bustling Jesuit style” as having no virtues and being a “mental delusion”.

Among French jewelers, the word baroquer means to soften the contour, to make the shape soft, picturesque. In French dictionaries, the word "baroque" appears since 1718 and is interpreted as an abusive expression. For a long time it could not become the name of the style. Back in 1904-1905. the largest French researcher S. Reinac does not seem to notice this style and an entire era in the development of European art, only casually and disparagingly recalling the “bustling Jesuit style” as having no virtues and being a “mental delusion”.

The first made the word "Baroque" typological category X. Wölflin. In the book Renaissance and Baroque (1888), written by him in Rome, and subsequent works, Wolflin defined Baroque as the highest, critical stage of development of any artistic style: the first stage is archaic, the second is classical, and the third is baroque.  In his famous “pairs” of formal concepts: linearity and picturesqueness, plane and depth, closed and open form, plurality and unity, clarity and vagueness — the first part Wölflin referred to the art of the classics, the second to the Baroque. Hence the opposition of Classicism and Baroque not only as concrete historical artistic styles of art, but also as the forms of shaping that are constantly repeated and updated in the history of the development phases.

In his famous “pairs” of formal concepts: linearity and picturesqueness, plane and depth, closed and open form, plurality and unity, clarity and vagueness — the first part Wölflin referred to the art of the classics, the second to the Baroque. Hence the opposition of Classicism and Baroque not only as concrete historical artistic styles of art, but also as the forms of shaping that are constantly repeated and updated in the history of the development phases.

The outstanding historian and philosopher of art M. Dvorak, an opponent of Wölflin, considered the Baroque style a product of Mannerism, but at the same time a higher level of "development of the spirit" in comparison with Classicism. The German cultural historian G. Weise "deduced" the Baroque style of the northern countries directly from the Gothic and considered him "the true embodiment of the German spirit" (Gemiit). The Baroque style was studied by X. Zedlmayr, a student of M. Dvorak, he finally approved the division of style introduced by Wölflin into the “early baroque” of the XVI-XVII centuries. (it. Fruhbarock) and "later Baroque" XVII-XVIII centuries. (Spat-barock). E. Malle, French scholar and scholar, in the 1920s. defined the Baroque as the "highest embodiment of the ideas of Christian art." Much later, the works of C. Gurlitt were discovered, which in the book The History of the Baroque Style in Italy (1887) anticipated many of the thoughts of X. Wölflin. Features of the art of "late Gothic" (Spatgotik) Gurlitt mystically brought together with the "spirit of the Baroque" (Gemut Barock). However, the classic Baroque country is still considered to be Italy.

The new art of the Baroque style has grown on the forms of Renaissance Classicism. The previous century in Italy was so strong in terms of art that its ideas, despite all the tragic collisions, could not disappear suddenly, they continued to have a significant impact on people's minds. And the masterpieces of the art of “High Renaissance” - works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael - seemed inaccessible. This is the essence of all the contradictions of the "Baroque era".  It was a time of painful changes in worldview, unexpected turns of human thought, partly caused by great geographical and natural-scientific discoveries.

It was a time of painful changes in worldview, unexpected turns of human thought, partly caused by great geographical and natural-scientific discoveries.

In 1445 I. Gutenberg laid the foundation for typography, in 1492 X. Columbus discovered America, Vasco da Gama in 1498 - the sea route to India. In 1519-1522 Magellan made the first circumnavigation of the world, by 1533, the discovery of the Earth movement around the Sun by Copernicus began to win recognition. The studies of Galileo, Kepler and the Newtonian "celestial mechanics" destroyed the previous familiar notions of a closed and immobile world, in the center of which is the Earth and man himself.

What had previously seemed absolutely clear, unshakable and eternal, began to literally crumble before our eyes.  Until that time, man, for example, was absolutely sure that the Earth was a flat saucer, and the Sun was setting behind its edge, which made it dark at night. Now they began to convince that the Earth is not a pancake, but a ball, and it also revolves around the sun. This was contrary to visual impressions. The man continued to see as before: flat, stationary earth and the movement of celestial bodies above his head. He felt the hardness of material objects, but scientists began to argue that this was just an appearance, but in reality nothing more than a multitude of pulsating centers of electrical forces. It was something to come into disarray.

Until that time, man, for example, was absolutely sure that the Earth was a flat saucer, and the Sun was setting behind its edge, which made it dark at night. Now they began to convince that the Earth is not a pancake, but a ball, and it also revolves around the sun. This was contrary to visual impressions. The man continued to see as before: flat, stationary earth and the movement of celestial bodies above his head. He felt the hardness of material objects, but scientists began to argue that this was just an appearance, but in reality nothing more than a multitude of pulsating centers of electrical forces. It was something to come into disarray.

True, the laws of Kepler were consistent with the Pythagorean theory of the music of the Heavenly Spheres, and Newton was in no hurry to make public his discoveries.  But, one way or another, these sciences came into conflict with the experience and the visible image of the world. An irrevocable psychological breakdown occurred - the basis of the future Baroque style. In the late XVI - early XVII centuries. discoveries in the field of natural and exact sciences have significantly shaken the image of a complete, motionless and harmonious universe, in the center of which is the “crown of Creation” - man himself. If recently, during the Renaissance, humanist scholar Pico della Mirandola argued in “Speech about human dignity” that a person in the very center of the world is omnipotent and can “see everything ... and own what he wants”, then in the 17th century Pascal wrote his famous words: a man is only a “thinking reed”, his inheritance is tragic, since, being on the verge of two abysses of “infinity and non-existence,” he is unable to grasp either one thing or the other, and turns out to be something average between everything and nothing ...

But, one way or another, these sciences came into conflict with the experience and the visible image of the world. An irrevocable psychological breakdown occurred - the basis of the future Baroque style. In the late XVI - early XVII centuries. discoveries in the field of natural and exact sciences have significantly shaken the image of a complete, motionless and harmonious universe, in the center of which is the “crown of Creation” - man himself. If recently, during the Renaissance, humanist scholar Pico della Mirandola argued in “Speech about human dignity” that a person in the very center of the world is omnipotent and can “see everything ... and own what he wants”, then in the 17th century Pascal wrote his famous words: a man is only a “thinking reed”, his inheritance is tragic, since, being on the verge of two abysses of “infinity and non-existence,” he is unable to grasp either one thing or the other, and turns out to be something average between everything and nothing ...

He perceives only the appearance of phenomena, for he is unable to know either their beginning or end. ”  And these are the words of the great mathematician! What are the opposite judgments on the same subject! Two epochs, two worldviews.

And these are the words of the great mathematician! What are the opposite judgments on the same subject! Two epochs, two worldviews.

Even earlier, in the first third of the 16th century, man began to acutely sense the contradictions between appearance and knowledge, the ideal and reality, illusion and truth. It was during these years that the views were formed, according to which, the more improbable a work of art, the more sharply it differs from that observed in life, the more interesting and attractive it is from an artistic point of view.

But this aesthetics was no longer consistent with the “Divine Ideal” of Raphael’s art; it was something else, an art that was later called Mannerism.

Baroque style slowly matured (to explode unexpectedly) in the architecture and sculpture of "High Renaissance". Amazingly, the greatest epoch in the history of fine art was short, only about ten to fifteen years. In 1519, Leonardo da Vinci was no longer alive, in 1520 Raphael died.  In addition, several opposing stylistic currents were destructive in this era, all of them were unstable and “did not correspond to reality”.

In addition, several opposing stylistic currents were destructive in this era, all of them were unstable and “did not correspond to reality”.

In this circumstance, the key to understanding the words of I. Grabar: “The High Renaissance is already three quarters of the Baroque”. Further, in the article “The Spirit of Baroque”, the Russian artist and art historian wrote: “Every day it became clearer that Alberti was“ not exactly what was needed ”, that even Bramante was already slightly pedantic and“ dry ”and was not so enchanting the abracadabra of the famous "golden cut" and the mathematics of proportions given in the facade of its "Cancelleria". And only when the frantic Michelanzhelo opened his Sistine booth and started capitol buildings, everyone understood what everyone was sick and hid in his heart ... and the new style - Baroque - was created. ”  We add that most of the murals on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Michelangelo “opened up”, removing the forests in 1509. And this was the highest peak of the “High Renaissance” in Italy!

We add that most of the murals on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Michelangelo “opened up”, removing the forests in 1509. And this was the highest peak of the “High Renaissance” in Italy!

The great Michelangelo by the power and expression of his individual style in one moment destroyed all the usual ideas about the "rules" of drawing and composition. Mighty figures painted by him on the ceiling visually “destroyed” the visual space reserved for them; they corresponded neither to the scenario, nor to the space of the architecture itself. Everything was anti-class here. J. Vasari, the famous chronicler of the Renaissance, amazed, like others, called this style "fancy, out of the ordinary and new."

Other works by Michelangelo: the architectural ensemble of the Capitol in Rome, the interior of the Medici Chapel and the lobby of the Library of San Lorenzo in Florence, showed classicistic forms, but all of them were covered with extraordinary tension and excitement. The old elements of architecture were used in a new way, primarily not in accordance with their constructive function. So in the lobby of the library of San Lorenzo Michelangelo did something completely inexplicable. The columns are doubled, but hidden in the recesses of the walls and do not support anything, so their capitals are some strange endings. The volutes hanging underneath them do not perform any function at all.  On the walls - imaginary, blank windows. But most of all surprises staircase lobby. According to the witty remark of J. Burckhardt, “it is suitable only for those who want to break their neck”. On the sides, where necessary, the stairs do not have a railing. But they are in the middle, but too low to be supported. Extreme steps rounded with completely useless curls at the corners. By itself, the staircase fills almost all the free space of the lobby, which is generally contrary to common sense, it does not invite, but only obstructs the entrance. In the project of the Cathedral of St. Peter (1546), Michelangelo, in contradiction to Bramante, who started construction, subordinated the entire architectural space to the central dome, making the building dynamic. Pilaster beams, twinned columns, dome edges depict a consistent, powerful upward movement. In comparison with the sketches of Michelangelo, the executor of the project Giacomo della Porta in 1588-1590. strengthened this dynamic by sharpening the dome; he made it not hemispherical, as was customary in the art of the Renaissance, but elongated, parabolic. Thus, the classic ideal of equilibrium was abolished, in which the visual aspiration from the bottom up seemed to be extinguished by the static nature of the semi-circular form. The new silhouette emphasized a powerful movement skyward.

On the walls - imaginary, blank windows. But most of all surprises staircase lobby. According to the witty remark of J. Burckhardt, “it is suitable only for those who want to break their neck”. On the sides, where necessary, the stairs do not have a railing. But they are in the middle, but too low to be supported. Extreme steps rounded with completely useless curls at the corners. By itself, the staircase fills almost all the free space of the lobby, which is generally contrary to common sense, it does not invite, but only obstructs the entrance. In the project of the Cathedral of St. Peter (1546), Michelangelo, in contradiction to Bramante, who started construction, subordinated the entire architectural space to the central dome, making the building dynamic. Pilaster beams, twinned columns, dome edges depict a consistent, powerful upward movement. In comparison with the sketches of Michelangelo, the executor of the project Giacomo della Porta in 1588-1590. strengthened this dynamic by sharpening the dome; he made it not hemispherical, as was customary in the art of the Renaissance, but elongated, parabolic. Thus, the classic ideal of equilibrium was abolished, in which the visual aspiration from the bottom up seemed to be extinguished by the static nature of the semi-circular form. The new silhouette emphasized a powerful movement skyward.

In 1607-1617 K. Maderno, who continued the construction, attached an elongated nave to the centric building and thus gave it a powerful horizontal dynamic. So as a result of rethinking the architectural space was born Baroque style. In a sense, there was a return to the ideals of Gothic. The same organic growth of forms, the same dynamics, irrationality, the predominance of the vertical over the horizontal.

"The Baroque style returned to the ideas of infinity," he not only "preserved, but even strengthened the sensual beginning of architecture." Not everyone could understand the new style. Even the romantics of the beginning of the XIX century, the Gothic admirers, considered him ridiculous.  The writer V. Hugo, who praised both the ancient and Gothic architecture, called the Cathedral of St. Peter in Rome "Pantheon piled on the Parthenon." At first, the architecture of the Roman Baroque still retained the classical composition, the symmetry of the facades, only enhancing verticalism and the picturesqueness of the order design of the walls. No wonder they notice that the early Baroque is close to the architecture of ancient Rome. At the same time, the Roman baroque churches, with their basilical plan and high, symmetrically located towers on the main facade, are strikingly reminiscent of Gothic ones in composition.

The writer V. Hugo, who praised both the ancient and Gothic architecture, called the Cathedral of St. Peter in Rome "Pantheon piled on the Parthenon." At first, the architecture of the Roman Baroque still retained the classical composition, the symmetry of the facades, only enhancing verticalism and the picturesqueness of the order design of the walls. No wonder they notice that the early Baroque is close to the architecture of ancient Rome. At the same time, the Roman baroque churches, with their basilical plan and high, symmetrically located towers on the main facade, are strikingly reminiscent of Gothic ones in composition.

It is characteristic that in the Baroque era, the facades of the Romanesque churches were converted into Baroque, because they seemed insufficiently expressive, and the Gothic ones remained intact. In many European cities, ancient cathedrals have towers with a new baroque end and the same baroque portals, in the interiors - baroque altars. Both Gothic and Baroque are united by expression, an irrational understanding of the architectural space. The advent of the Baroque era meant the return of romance to the architecture of Christian churches. After the centric buildings of F. Brunelleschi and D. Bramante, who do not respond to religious spirituality (after all, the Pazzi or Tempietto chapel is less like a temple), a revival of true Christian art took place. In this sense, O. Spengler’s statement about the evolution of Michelangelo’s creativity is remarkable: “Out of the deepest dissatisfaction with art for which he spent his life, his everlasting need for expression smashed the Renaissance architecton canon and created the Roman Baroque ...” And in the face of Michelangelo the sculptor "The history of European sculpture has ended."

Indeed, Michelangelo is a true “father of Baroque”, since in his statues, buildings, drawings there is, at the same time, a return to the spiritual values of the Middle Ages and the consistent discovery of new principles of shaping.  This brilliant artist, having exhausted the possibilities of classic plastics, in the late period of his work created unprecedented expressive forms. His titanic figures are depicted not by the rules of plastic anatomy, which served as the norm for the same Michelangelo only some ten years ago, but according to other, irrational shaping forces caused by the imagination of the artist himself. One of the first signs of Baroque art: excess funds and a mixture of scales. In the art of classicism, all forms are clearly defined and delimited from each other. They are commensurate with the viewer; sculpture and architecture are also separated, and although decorative statues and paintings are associated with the architectural space, they always have framing and clear compositional boundaries. Michelangelo's “Sistine ceiling” is therefore the first work of the Baroque style that a collision of painted but sculpted figures by the tactile nature and an incredible architectural frame painted on the ceiling, not at all coordinated with the real space of architecture, occurred in it. The size of the figures also mislead the viewer, they do not harmonize, but dissonate even with the picturesque, illusory space created for them by the artist.

This brilliant artist, having exhausted the possibilities of classic plastics, in the late period of his work created unprecedented expressive forms. His titanic figures are depicted not by the rules of plastic anatomy, which served as the norm for the same Michelangelo only some ten years ago, but according to other, irrational shaping forces caused by the imagination of the artist himself. One of the first signs of Baroque art: excess funds and a mixture of scales. In the art of classicism, all forms are clearly defined and delimited from each other. They are commensurate with the viewer; sculpture and architecture are also separated, and although decorative statues and paintings are associated with the architectural space, they always have framing and clear compositional boundaries. Michelangelo's “Sistine ceiling” is therefore the first work of the Baroque style that a collision of painted but sculpted figures by the tactile nature and an incredible architectural frame painted on the ceiling, not at all coordinated with the real space of architecture, occurred in it. The size of the figures also mislead the viewer, they do not harmonize, but dissonate even with the picturesque, illusory space created for them by the artist.

The architecture of Baroque strikes "inhuman" scale. Portals and windows ten times more than human growth became the norm. Rule - infinite repetition, duplication of the same techniques. I. Grabar writes about the Roman architecture of the Baroque epoch: “Neurasthenic enthusiasm doubles and triples all means of expression: there are few individual columns, and they are replaced with steam where possible; one pediment seems insufficiently expressive, and they do not hesitate to break it, in order to repeat in it another, smaller scale. In pursuit of the pictorial play of light, the architect opens the viewer not all forms at once, but presents them gradually, repeating them two, three, and five times.  The eye is confused and lost in these intoxicating waves of forms and perceives such a complex system of rising, descending, departing and impending, now stressed, now lost lines, that you do not know, which of them is correct? Hence the impression of some kind of movement, the continuous running of lines and the flow of forms. This principle reaches its highest expression in the reception of “raskrepovok”, in that repeated crushing of the entablature, which causes at the top of the building an intricately curving line of the cornice.

The eye is confused and lost in these intoxicating waves of forms and perceives such a complex system of rising, descending, departing and impending, now stressed, now lost lines, that you do not know, which of them is correct? Hence the impression of some kind of movement, the continuous running of lines and the flow of forms. This principle reaches its highest expression in the reception of “raskrepovok”, in that repeated crushing of the entablature, which causes at the top of the building an intricately curving line of the cornice.

This reception was erected by baroque craftsmen into a whole system, unusually complex and complete. This also includes the reception of group pilasters, when pilasters still get half pilasters on the sides, as well as the reception of flat frames framing the inter-pilaster intervals. ”  The harmony created a "ghostly feeling."

The harmony created a "ghostly feeling."

The compositional techniques listed by I. Grabar can be combined with the concept of forcing a form (Italian forzare from lat. Fortis - force), enhancing it with rhythmic repetitions, giving the impression of visual syncopation (from the Greek. Synkope - reduction, loss). The use of such a technique is indicative: inscribing a triangular pediment into an arched one (in the relatively restrained baroque facade of the Il-Gesu church in Rome, built by Giacomo della Porta according to the design of J. Vignola in 1575-1584). Strengthening the irrationality of architecture led to the fact that the facade no longer “told” what was inside the building, but, on the contrary, obscured the building, became a decoration, and the inner space, its grandeur, proportions and extraordinary dimensions should have been a surprise to the viewer.  The calculation was made on surprise, contrast, surprise of the impression. Instead of centric in terms of buildings created elongated basilic. It is also characterized by a return from Classicism to Gothic, and even to Romanesque prototypes. A decorative type of the facade, like a theater curtain or even a “backdrop” covering the volume of the church building, was formed in the art of the Italian Renaissance, but received a complete expression in the Baroque era. The circle, the favorite form of Renaissance artists, gives way to a more dynamic oval, the square is replaced by a rectangle; a rational system of proportions based on the relations of simple integers, so long improved and so brilliantly demonstrated in the buildings of A. Palladio, is again replaced by Gothic triangulation - constructions based on a triangle - the symbol of Divine harmony. Fantasy architect spent on creating fancy plans of cleverly composed triangles, ovals, stars and pentagrams. These plans themselves are not visible, but they gave impetus to unexpectedly dynamic exteriors and interiors. Such are the buildings of the outstanding Roman Baroque architect F. Borromini, a disciple of C.Maderno.

The calculation was made on surprise, contrast, surprise of the impression. Instead of centric in terms of buildings created elongated basilic. It is also characterized by a return from Classicism to Gothic, and even to Romanesque prototypes. A decorative type of the facade, like a theater curtain or even a “backdrop” covering the volume of the church building, was formed in the art of the Italian Renaissance, but received a complete expression in the Baroque era. The circle, the favorite form of Renaissance artists, gives way to a more dynamic oval, the square is replaced by a rectangle; a rational system of proportions based on the relations of simple integers, so long improved and so brilliantly demonstrated in the buildings of A. Palladio, is again replaced by Gothic triangulation - constructions based on a triangle - the symbol of Divine harmony. Fantasy architect spent on creating fancy plans of cleverly composed triangles, ovals, stars and pentagrams. These plans themselves are not visible, but they gave impetus to unexpectedly dynamic exteriors and interiors. Such are the buildings of the outstanding Roman Baroque architect F. Borromini, a disciple of C.Maderno.

In the church of San Ivo, built by Borromini in 1642-1660. (see “Jesuit style”), the structure of the plan consists of two crossed equilateral triangles - “Star of David”, and instead of the traditional dome a spiral is screwed into the sky with semi-exotic semi-baroque turrets-phials and some kind of crown with a ball and a cross at the top.  The facade of the church of San Carlo "at the four fountains" in Rome (1638-1667) Borromini decided in the form of a combination of convex and concave walls and cornices with a huge oval cartouche, causing concern because of its enormous dimensions and ambiguity of attachment. The most important feature of Baroque architecture can be defined as the tendency to change the tectonic beginning of the aectonic, sculptural - plastic, graphic - pictorial.

The facade of the church of San Carlo "at the four fountains" in Rome (1638-1667) Borromini decided in the form of a combination of convex and concave walls and cornices with a huge oval cartouche, causing concern because of its enormous dimensions and ambiguity of attachment. The most important feature of Baroque architecture can be defined as the tendency to change the tectonic beginning of the aectonic, sculptural - plastic, graphic - pictorial.

If the architecture of Classicism is built on a clear visual division of the carrier and bearing parts, then in the buildings of the Baroque style, these relationships are intentionally confused. In the Greek Parthenon, the gaps between the columns are as essential as the supports themselves, but their functions are different not only in a constructive, but also in a compositional sense. Verticals contrasted with contours, flutes with abacus, triglyphs with metopes.  For Baroque art is characterized by "fear of emptiness" (lat. Horror vacui). And this is not just a beautiful metaphor, but a consistently held principle of shaping.

For Baroque art is characterized by "fear of emptiness" (lat. Horror vacui). And this is not just a beautiful metaphor, but a consistently held principle of shaping.

The space of architecture, the plane of the wall or the ceiling is filled with an abundance of details so that they hide constructive partitions. The sculptural principle, characterized by clarity of boundaries and closure of forms (both in the sculpture itself and in architecture and decorative paintings), is supplanted by the opposite - plastic principle, meaning the freedom of the “flow” of form from one part of it to another. Everything together creates a picturesque, in which the boundaries of architectural design, sculptural, relief and picturesque decor disappear.  Such methods of deliberately mixing the “framing” and “filling” functions, arrhythmias, “going out of the frame” are called anacoluf in the literature (Greek anakoloythos - inconsistent, incorrect). An additional means of "forcing the beauty" is the play of color and light, the streams of which flow from everywhere, from the most unexpected sources and in contrasting directions. Not only the columns, but also the walls are no longer perceived as pillars, delimiting the internal space from the external; they seem to be the “excitement of the masses” who are about to explode from within. This is another distinction of Baroque architecture from the buildings in the style of Mannerism, in which the wall also visually depreciates, but remains a ghostly screen, a transparent wall in a richly ornamented frame.

Such methods of deliberately mixing the “framing” and “filling” functions, arrhythmias, “going out of the frame” are called anacoluf in the literature (Greek anakoloythos - inconsistent, incorrect). An additional means of "forcing the beauty" is the play of color and light, the streams of which flow from everywhere, from the most unexpected sources and in contrasting directions. Not only the columns, but also the walls are no longer perceived as pillars, delimiting the internal space from the external; they seem to be the “excitement of the masses” who are about to explode from within. This is another distinction of Baroque architecture from the buildings in the style of Mannerism, in which the wall also visually depreciates, but remains a ghostly screen, a transparent wall in a richly ornamented frame.

In authentic Baroque, the wall is aggressive, tense and dynamic. Particularly interesting are the concave facades, as if drawing in the surrounding space together with suitable people who are too close, and walls converging at an acute angle, cutting the space like a knife. The columns of the most magnificent Corinthian order were placed on high pedestals. But this also seemed insufficient: the columns gathered in groups, bunches and, moving away from the wall, together with the powerfully unfixed eaves, created a feeling of uncertainty — now the speakers, now the receding volumes.

Chiaroscuro intensified the effect. Statues in the niches and on the roof of buildings along with balustrades also created a feeling of fragility, blurring of boundaries, dissolving architectural forms in space. The next principle of formation, opened in the art of Baroque style, is the monumentalization of decor. For art of previous eras, especially Gothic, is characterized by a different principle - miniaturization. The forms prevailing in the architecture — columns, arches, domes — diminished and became elements of the decoration of furniture and metal products. Thus, the Gothic silver monstrans reliquaries are a reproduction of a Gothic cathedral in miniature. The architectonic miniature altars and Zion are the same. The furniture, the construction of which followed the architecture, was decorated with arcatures, turrets, spiers, balustrades. In Baroque - the opposite is true. As far back as the Renaissance, F. Brunelleschi decorated the lantern of the dome of the Florentine cathedral with what he saw in ancient monuments with krashteynami. He turned them on ninety degrees and turned into decorative curls - volutes. Baroque made these volutes gigantic. It is these volutes that we see on the facade of the Il-Gesu church in Rome. The volute's shape is extraordinarily dynamic, it picturesquely connects the vertical and horizontal, top and bottom, softens the corners and this is loved by many Baroque-style artists. The most famous opus of the monumental decor was created by the “genius of the Baroque” - L. Bernini. In the interior of St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, above the tomb of Apostle Peter, he erected a huge, unreasonably enlarged tent — a civorium 29 meters high (the height of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome). From a distance, a tent of blackened and gilded bronze on four twisted columns with "curtains" and statues from the nave of the cathedral seems just a toy, a fad of interior decoration. But close - stunning and depressing, turning out to be a colossus of inhuman scales, which is why the dome above it seems as immense as the sky.

Another famous Italian Baroque architect, G. Gvarini, worked mainly in Turin, was a mathematician and professor of philosophy. Based on the absolute harmony of mathematical relationships, Guarini most paradoxically, in the spirit of the Baroque, was able to create a mystical sensation in her buildings. In Rome, built K. Rainaldi, a follower of Bernini. In Venice - B. Longena, the creator of the original baroque architecture of the church of Santa Marna della Salute (1631- 1682). Important for the development of Baroque architecture was the construction of the Palazzo Barberini in Rome. Bolonets S. Serlio, a theorist of the late Renaissance architecture who was inclined to Mannerism, tried to substantiate the methods of dissonance, mixing of scales and principles of proportioning. He proposed that each next floor of the building be made one quarter lower than the previous one. Seen from below, it created a “forzato” feeling.

Even more clearly, this feature of the Baroque style was expressed in the works of the architect and sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 - 1680). The main features of Bernini's creativity are unnatural, artificiality, theatricality, and fake. It becomes clear dismissive and hostile attitude to the art of Baroque from the "classics" and "academics". In front of St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, Bernini built a colonnade - typically theatrical scenery. It hides the chaotic building of the city behind it and at the same time forms an illusory, not corresponding to real, space of the square.

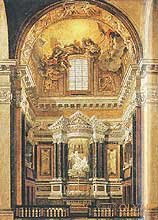

Such are also other Roman projects of Bernini the architect: squares with fountains and obelisks, streets “pierced” in defiance of the existing layout of the city, theatrical facades covering the buildings. In the interior of the Cathedral of St. Peter, the main author of which was also Bernini, not only a huge ciborium, but all the decoration - giant sculptures (they would seem alive, if not for their incredible size), a chair with statues in streams of light pouring from above - all it is a theater, an irrational theater. As a person moves towards the crosshair and the altar changes, space grows. Twisted columns of the civorium are screwed up, the dome rises to a dizzying height, light streams, statues hang and at some point a person begins to feel completely crushed, lost before the superhuman, monstrous scale of what he saw. This is truly a cosmic surge of matter! The forms themselves are naturalistic, they are only put in extraordinary conditions. This creates a paradox. This is how Bernini works. Roughly and straightforwardly, it forms an artistic image by primitive non-artistic means. His compositions give a sham, tasteless theatricality. Bernini proudly declared that in sculpture he subjugated to himself the form, "making marble as flexible as wax." We can say that he makes his spectator as soft as clay. This artist attracts, then repels, and even completely crushes with its power and unbearably coarse effects.

Stendal at the beginning of the XIX century. rightly remarked: "If a foreigner, having come to the Cathedral of St. Peter, decides to inspect everything, he will experience a severe headache." In the famous composition “Ecstasy of St. Theresa”, in the chapel of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria (1647-1622), the heavy marble of the figures, pierced by streams of light, pouring from above, seems soaring, weightless. The sculptural group turns into a mystical vision (Fig. 495). Bernini is a master of artistic mystification, his statement that he made marble as flexible as wax has a continuation: “With this I was able to combine sculpture with painting to some extent.” This artist combined marbles of different colors, and the heavy details of gilded bronze — the garments of the figures — develop through the air, as if there is no gravity. There is a dematerialization of forms. It is also one of the characteristic features of the Baroque style.

The architecture becomes extremely picturesque, and the sculpture and painting are "incorporeal." The artistic style of the Italian Baroque is closely connected with the ideology of Catholicism and the movement of the Counter Reformation. Increased expressiveness, mysticism, illusionism, immateriality peculiar to the Baroque, are inherent in the Catholic worldview. Therefore, in Italy XVI-XVII centuries. there was a combination of baroque forms created by artists as a result of the natural evolution of the art of classicism, and the official ideology of the Vatican. It is not by chance that one of the main stylistic currents of the Italian Baroque is called “Jesuit style”, or Trentino. He was headed by an architect, painter, sculptor and art theorist, a member of the Jesuit Order A. Pozzo. This artist is the author of the painting of the ceiling of the Church of St. Ignatius in Rome (1684). The theme of the composition is “Apotheosis” - deification, the ascension of the head of the Jesuit Order Ignatius Loyola to the sky. The painting is striking in its illusiveness and, at the same time, the power of fantasy, religious ecstaticism. Ceiling paintings - a favorite type of Baroque art. The ceiling or surface of the dome made it possible to create illusionary decorations of colonnades and arches that go up and using the means of painting and “open” the sky, as in the hyperal temples of antiquity, with figures of angels and saints hovering in it, not subject to the laws of the earth, but fantasy and the power of religious feeling . This experience is well expressed in the words of I. Loyola himself: “There is no spectacle more beautiful than the host of Saints who are carried away to infinity.” New artistic ideas were freed from everyday reality that binds them, conditions of “credibility”, from classical canons. This made it possible to eliminate material constraints: visually “break through the plane of a wall or ceiling, ignore frames, constructive partitions of architecture, or create new ones, illusory ones. Picturesque compositions that depict “fraudulent” architectural details that create a smooth, imperceptible transition from real architecture to fictional, invented by the painter, have become typical. Sometimes the ceiling depicted the inner space of a dome with a hole, as in the Roman Pantheon, through which the sky could be seen with soaring clouds. The main artistic idea of the Baroque is active influence, psychological submission, but not for silent awe, intimate, in-depth contemplation, but for action, movement. Baroque is active, dynamic, it requires unconditional obedience.

In the XVII century. in Italian Catholicism there was a course of Quietism (from the Latin. quietus - quiet, serene), associated with the approval of the submissive and absolutely impassive submission of man to the divine will and ecclesiastical authorities. The fact that the great secular, Flemish baroque painter P. Rubens in his youth studied at the Latin Jesuit school in Antwerp indirectly testifies to the role of Catholicism’s ideology in the spread of Baroque outside the “Jesuit style” itself. There he received a brilliant knowledge of Latin, ancient mythology and mastered six more languages. The ideological duality of the Baroque style was expressed in the fact that instead of the traditional concept of composition, introduced by L.A. Alberti, a theorist of the art of the Italian Renaissance, the expression “mixtum compositum” (Latin “mixed mix”) turned out to be more suitable. It accurately conveys the idea of connecting the incompatible - the quintessence of baroque. But the main criterion, as in the aesthetics of Classicism, remains “beauty”, it is interpreted only ideally: “you can get close to it, but it cannot be mastered”. Bernini said that nature is weak and insignificant, and therefore to achieve beauty, it is necessary to transform it with a force of spirit similar to religious ecstasy; art above nature as well as spirit above matter, as a mystical illumination above the prose of being. Baroque artists were looking for beauty not in nature, but in their imagination, and found it, paradoxically, in classical forms. After all, ancient statues already contained an idealized nature. Therefore, Bernini advised to begin learning art not by working from life, but by drawing molds of ancient sculpture. Here the aesthetics of the Baroque style merged with the ideas of academic art. Following the beauty, the theorists of Baroque art called the category of grace (Latin gratia - charm, elegance), or Cortesia (Italian cortesia - politeness, tenderness, warmth). These qualities gave the art form plasticity, variability, fluidity.

Another important category - “decorum” - the selection of relevant topics and stories. They include only the "worthy": historical, heroic. Still life and landscape are declared lower, "unworthy" genres, and traditional mythological subjects are subjected to "processing" and "censorship." Portrait - is recognized only when he expresses "nobility and greatness." Bernini often speaks of "big style" and "big style" - these are his favorite terms. He resorts to them when he wants to emphasize solemnity, special pathos and decorative scope of true Baroque. The category of “majestic” gradually comes to the first place, it is denoted by the Latin word “sublimis” - high, large, elevated. In the ceremonial portraits of the Baroque epoch, the enlarged, weighted forms of luxurious robes, draperies, and architectural background are permanent. Standard accessories: colonnades, balustrades, flying geniuses of Glory, ancient altars, and figures portrayed in growth, likened to the monuments, gave rise to the name - "a large statuary style." Famous masters of this style were A. Van Dyck and J. Reynolds in England, S. Lebrun and I. Rigaud in France (see “The Big Style”), V. Borovikovsky in Russia (see Catherine’s Classicism).  Artificial exaltation, theatricality has become: luxurious, divine, brilliant, magnificent.

Artificial exaltation, theatricality has become: luxurious, divine, brilliant, magnificent.

& nbs

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)