Already for countless millennia, all kinds of living creatures have lived on earth; entire worlds of heterogeneous plants and animals, partly found in petrified form under the earth's surface, had time to emerge and disappear when a man appeared, took possession of the earth as his heritage, and began to conquer all other cohabitants or force them to serve themselves as far as he needed. When the end of this phenomenon comes, it cannot be said. Its beginning is shrouded in darkness, which has become illuminated by the first, weak and dim rays, thanks to the discoveries and findings of prehistoric times made by the last generations of people. The most ancient epoch, in which undoubted traces of human activity are discovered, is still a “Quaternary epoch”.

French researchers (de Mortilla) see the oldest traces of a quaternary man in France, in a warm, damp "preglacial era", medium - in the actual "glacial epoch", and later in the "new glacial epoch". We must, however, provide these questions to natural science. In any case, undoubtedly, the glaciers of the diluvial glacial epoch were already diminishing at a time when the inhabitants of Europe, north of the Pyrenees and the Alps, hunted the hairy rhino, mammoth, horse, reindeer and cave bear. Most Belgian scientists, namely Dupont and van Overloop, argue that the era of the mammoth preceded the era of the reindeer. The great English explorers of prehistoric times, such as Löbbock and Boyd-Daukins, do not attach importance to this division; in fact, judging by the layers in which fossils are found, reindeer from the very beginning comes along with the mammoth, but the mammoth disappears much earlier than the deer. Therefore, the era of the reindeer can be called the entire period under consideration, the era of the mammoth - only the first half of it.

The European of this gray-haired antiquity stood on the steps of the so-called lower primitive peoples. He was a hunter and fisherman, he did not know any dwellings, except caves, other roofs, except natural canopies of rocks or tree branches, to which, perhaps, he attached tents made of stakes and animal skins, did not know any other clothes than hides, other yarns and ropes, in addition to belts made from animal skin, veins and intestines, and other implements, except for wooden, bone, horn, and stone. From the very beginning we see him as the owner of the fire. "Coals and fragments of flint," says Johann Ranke, "are the most ancient traces left by man on earth." Perhaps the then European already knew how to weave baskets and mats, but he could neither spin, weave, nor sow, nor collect the harvest. We can’t even attribute to this diluvial person even the ability to make pots of clay and burn them. The dog has not yet become his companion, and he has not yet started other domestic animals; apparently, even the horse and cattle were known to him only as objects of hunting.

The main signs of this stage of human development are, on the one hand, the unfamiliarity of people with metals, and on the other, the preference they gave stone, especially flint, for making weapons and tools. Therefore, this stage is also called the Stone Age. However, this epoch embraces not only the period of mammoth and reindeer, but also the next closest major stage of human development, usually contrasted by the oldest stone, or Paleolithic, era, and we will first of all talk about art, calling it the newest stone, or neolithic, an era.

Traces of the oldest, actually diluvial stone age, which, according to Virkhov, is removed from us, "perhaps for tens of thousands of years or more," we find both in Central and Southern Europe, and in Africa, Asia and America, but only In the west of Central Europe, traces of human activity of this ancient era that have artistic significance have been found. The most ancient products of human hands in Central Europe are tools and weapons, but the goal of each individual item belonging to them is not always easy to determine. Between them there are axes, hammers, scrapers, stone knives, made mainly of flint, daggers, drill bits, stone or bone lances of spears and arrows, sewed, needles, fishing rods, harpoons with hooks made of bone or antler, mainly deer.

The difference between the oldest and later stone eras is most clearly seen in the difference in the shapes of stone utensils. Stone tools of the most ancient stone era are not yet polished and not polished; they were only pounded out for smoothness with a flat stone, and subsequently leveled by means of pressure (pfiriode de la pierre taillfie), covered with strips by scraping and sharpened symmetrically.

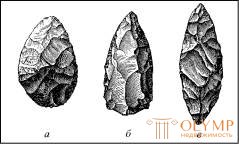

Fig. 2. The flint edges of the oldest stone age

The edges of the spears or arrows of the diluvial era in Solutra are already known for their shape, resembling a bay leaf or a willow leaf, and their surface is covered with regular stripes. French science has created a whole history of the development of diluvial flint utensils, thanks to extremely rich finds in France; four stages of this history are commonly referred to by science according to the types prevailing in Shell (Seine and Marne), Le Moustier (Dordogne), Solutre (Saône and Loire) and La Madeleine (Dordogne); Recently, Salmon, eliminating the third stage, established three Paleolithic and three Neolithic stages, and thus divided the entire Stone Age into six divisions. In all these divisions, of course, there are many arbitrary. But just look at the pictures in fig. 2 and stored in the museum in Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Saint-Germain-en-Laye) flint tips to see that from type A from Shell to type B from Le Moustier, and from the last to type in from Solutre In these objects, noticeably improved form, indicating internal development, the first development in the field of human dexterity and skill, which deserves our attention.

Further, glimpses of the striving for art among the Europeans of the Paleolithic era are found in the numerous components of the chains, which were used for decoration and made of animals pierced and strung on a tooth chain, shells, ammonites, roughly processed pieces of bone or stone, objects obtained from the diluvial layers. in various localities. There are also untreated pieces of amber and remnants of red paint, which primitive people used to grind themselves. Self-decoration everywhere was a man's innate need.

However, the history of art would not have had a reason to climb into the inhospitable caves of the glacial age, if the first rays of real, free art, which aimed solely for itself, did not shine from their dark depths with magical light. Since the revival of this original art from the depths of the earth, only one generation has lived, but thanks to more and more new discoveries and discoveries, the character of this art becomes more and more apparent with each decade.

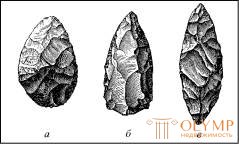

Fig. 3. Drawings on the bone and stone implements of the most ancient times of the Stone Age. According to Lart and Christie (1, 2, 6, 13), de Mortilla (4, 8, 9), Merck (5, 7, 10, 11) and Kartalyaku (12)

Although at the head of this art, as we shall see, there is an image of a man and in it linear ornamentation plays even an independent role, however, this art attracts us mainly with its simple, life-like truthful images of animals, partly carved with a flint cutter or knife, like plastic figures from deer horns , bones or mammoth fangs, part of a flint-point that has been scratched in the form of contours on stone slabs or on things made of deer horn or bone, and the contours are sometimes so deep that the figures animal half is embedded in the subject. Herbivores, which can be observed in a more peaceful state, are depicted much more often than predators; most of all there are images of deer and wild horses of small breed with a thick head. They are represented quietly standing or herding, sometimes running or lying, and herd animals, like horses and reindeer, are often depicted three or four, running or standing one after another.

We will have to meet more than once the fact that a primitive person who is at the level of hunting and fishing peoples is more likely to catch the eye of the animal world, which they have to wage a constant struggle than the world of plants, and that therefore the artistic images of animals are more basic. cultural stage. Only in relation to the world of animals, the hunter exercises his eye and hand, only the world of animals can he understand so subtly and so clearly convey that their images make a true, vital and, therefore, artistic impression. Images of plants, even decorations from plants, are almost completely absent in this primitive art.

The best images of animals belonging to the most ancient stone age are on strange objects made of bone or pieces of deer antler, on the broad end of which one or several round holes were drilled (Fig. 3, 10-13). At first, these pieces served as military weapons, and then with the rods of military leaders or even the insignia of the leaders. Boyd-Daukins, comparing them with similar, but even more rough and angular objects of the Eskimos, recognizes them as tools for pulling arrows. All in all, it seems to come closer to the truth of the Reinachs, saying that these sticks did not at all serve as any tools, but were luxuries, mainly hunting trophies. We will call them simply decorative sticks, without giving this name special meaning.

The vast majority of artfully decorated objects of the diluvial era are found in the caves of South-Eastern France. From the time when Larte and Christie in 1863 explored the caves of the Weser Valley in the Dordogne department and there, in the cave of Les Eyzies and under the sheds of the La Madeleine and Laugerie Basse cliffs, little by little they discovered the objects of art that they described during the next decade in the work "Reliquiae Aquitannicae", since then the number of finds in these areas has increased to such an extent that it is almost impossible to list them. The greatest number of the most curious works of this kind are found in caves at the foot of the Pyrenees. The excavations of Piett were especially successful here, who also undertook the publication of a large essay about his research. The collection of his finds from Ma-d'Asil attracted the attention of visitors to the Paris World Exhibition of 1889; His later excavations at Brassampui deserve even more amazement.

In England, namely, in a cave in Derbyshire, as they say, only one piece of bone with a horse's head scratched on it was found. The caves of the diluvial era in Belgium were also not rich in works of this kind. In Austria, in Löss, near Brunn, the broken figure of a naked man carved out of a mammoth's fang was dug out, which we, together with Makovsky, refer to the diluvial era, as it is, in its style, close to the finds in the Dordogne. In Germany, near Andernach, only one piece of deer antler was found, carved in the shape of a bird; It is kept in the provincial Bonn Museum. The finds in France are not inferior in meaning to the artistic monuments of the diluvial stone age, discovered in 18731874. in German Switzerland, in the Shafgauzensky canton, in Kesslerloh, near Taingen, Merck, and in 1892 near Schafgausen Nyush. These two sites of excavation belong to the most important of all, hitherto known. A great surprise was aroused by Tayingen antiquities, which were the subject of detailed study at the anthropological congress in Constanta in 1877. Some German scientists doubt the authenticity of the whole find, while images of a fox and a bear engraved on bones are considered rude forgeries attached to this find only afterwards. In particular, doubting scientists found it difficult to recognize as genuine the famous "grazing reindeer" (see Fig. 3, 11), which Game pointed out, namely as a result of the art with which he was traced. But for an experienced eye, developed in artistic and historical terms, the conclusion is quite the opposite: the images of the fox and the bear, now kept in the British Museum, with their form, completely dissimilar to all other products of this kind, prove the authenticity of other drawings.

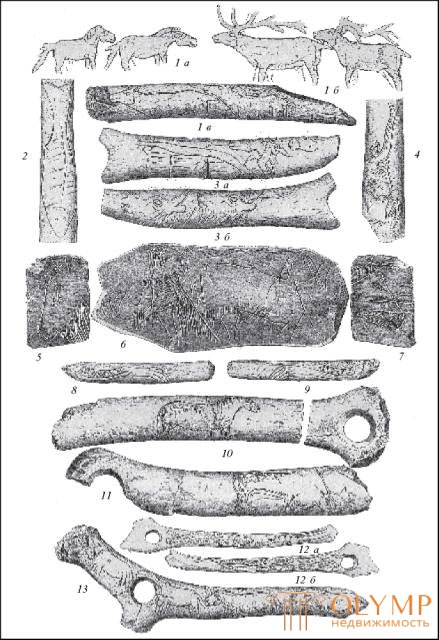

Fig. 4. Venus Brassampouy. By piett

The first who tried to build the history of the development of the original art we considered on the basis of French finds was Piett. Since Görnes (Hoernes) in his extensive work on the original history of the figurative arts joined the views of Piett, these views have gained universal importance. Unfortunately, we cannot verify their correctness by studying the sequence of layers in which these finds are made, but the well-known natural correct sequence undoubtedly favors the above-mentioned views. They proclaim that the round plastic is ancient than the relief and scratching of images, that the image of a person is older than the image of animals, and the image of animals is older than a geometric ornament.

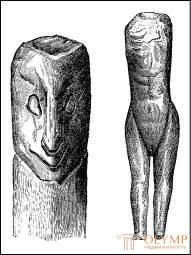

The oldest surviving round plastic statues, and therefore the oldest of the works of art that have come down to us all over the world, are, according to the data, fragments of small female figures of the mammoth age carved from tusks (found in 1892 and 1894 in Brassampui, in the south of France, and are kept in the Pietta collection in Ryumini), primarily the female torso, dubbed "Venus Brassampouy" (Fig. 4) and distinguished by a somewhat awkward completeness of its forms. A similar torso in the same collection is found in Ma d'Azil. To these finds is a female figure found near Menton and described by Reinach; suspicion of its authenticity is probably unfair. As you can see, a woman is on the verge of art. These female figures are more ancient than the oldest male figures found in Loess, near Brunn, and stored in the museum of this city.

Among the long-found human figures of the diluvial era, two are particularly noteworthy. In the collection of the Paris Anthropological School, there is a piece of deer antler, open in the Rochebertier Cave (in Charonte), at the top of which represents an ineptly carved human figure (Fig. 5, a); From the de Vibre collection, a wonderful little female torso is found, which was found in Lodge-Bass (Fig. 5, b) and is now kept in the Paris Natural History Museum. Although the torso has neither a head, nor arms, nor the lower part of the legs, however, this small figure carved out of a canine indicates that the one who made it already understood the mutual relation of the parts of the body. If the figure from Rochebrier is almost no different from the most formless idol-chumps that we see in wild nations, the figure from Lodge-Bass represents a step forward in the sense of reproducing the human body, and even ancient times do not always reach this level. These figures were probably not idols and toys, but free creations of the innate desire for art. First of all, we see in them attempts to depict a person and, judging by their fragments, we find that in their body and head they represented that strict symmetry, which Julius Lange considered to be a sign of all statues before the heyday of Greek plastics and which he called "frontality". But at the same time - what a difference, in understanding and in the transfer of forms!

Fig. 5. Human figures carved from reindeer antlers and mammoth tusks. By G. G. Muller and Kartalyaku

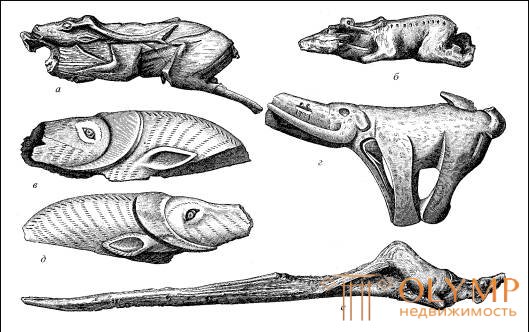

After the woman, as Görnes perfectly noted, the artist attracts the attention of wild animals, which he and his relatives hunt for. Most plastic images of animals, apparently, served as knob handles, as we can judge from the handle of the dagger from Lodgeier-Bass in the museum of Saint-Germain-en-Leu (Fig. 6, e). But this is not recognized by all. A piece of musk ox from Taingen, cut out of deer antlers and kept in the Rozgarten Museum, in Constance, which can be recognized by curved down horns (Fig. 6, c), as well as the mammoth from Brunikel (Fig. 6, g ), carved from a horn, flattened laterally, with legs joined together, stored in the British Museum, testify to some archaic lack of understanding and transmission of body forms. But the forms of the two carved reindeer from Brunikel’s fangs (Fig. 6, a and b), which are also in the British Museum since 1887, are distinguished by much greater clarity and vitality; северный же олень, вырезанный из рога и составлявший рукоятку упомянутого кинжала из Ложери-Басса, свидетельствует о таком значительном понимании форм и о таком ловком приспособлении движения животного к форме рукоятки, до каких историческое искусство дошло лишь после долгой борьбы. Взгляните, как естественно и вместе с тем "стильно" животное откинуло свою голову назад, плотно прижало рога к спине и вытянуло задние ноги, переходящие в рукоятку! Другие подобные изображения обнародованы Пиеттом (кстати, изумительно натурально воспроизведенные лошадиные головы).

Среди нацарапанных контурных рисунков и изображений, вырезанных плоским рельефом, столько переходов, что, хотя последние и можно считать вообще более древними, чем первые, однако нельзя отделить от них. Замечательны геометрические орнаменты, которые иногда встречаются на телах животных. По-видимому, это намеки на шерсть. Нечто подобное мы найдем в искусстве позднейших времен уже в виде явственно выработанного орнамента. Человеческие фигуры в произведениях этого рода встречаются только в связи с изображениями животных. Из таких фигур знаменит "охотник на зубра" из Ложери-Басса, хранящийся в коллекции Массена. Это изображение нацарапано на оленьем роге. Зубр представлен жизненнее и лучше, чем его нагой преследователь, который точно падает вперед, тогда как царапавший хотел представить его в прямом положении. Упомянем еще о куске оленьего рога из Ла-Маделена (в Сен-Жермене), на одной стороне которого изображен обращенный вправо человек с палкой на плече, слегка присевший перед двумя лошадиными головами, начерченными в гораздо более крупном масштабе; другая сторона куска украшена двумя весьма живо представленными козлиными головами (см. рис. 3, 3а и 3б). Замечательны также некоторые изображения одних только рук, кисти которых постоянно даются только с четырьмя пальцами, как это видно, например, на предметах из Ла-Маделена, хранящихся в Британском музее (см. рис. 3, 8 и 9).

Fig. 6. Plastic images of animals belonging to the oldest stone era. According to the cast of the Dresden Museum (a, b, d, e), according to Merck (c)

All animals of this kind are only in profile. It is extremely curious that at the same time the most skilled artists already knew how, at least in the image of a simple movement - step, to separate the legs, turned towards the viewer, from the legs behind. Further, two bars with images of wild horses and reindeers (see Fig. 3, 1a, b, c and 13), originating from La Madelena and stored in the British Museum, were skillfully made, as well as a fragment of fish found in the same place. on each side (see fig. 3, 2); Remarkably well-known in the Paris Natural History Museum is the famous, which made a lot of noise and triumphantly defeated all the nagging images of a mammoth on the canine teeth of this animal, found in La Madeleine (see Fig. 3, 6), and the bar from Mongodieu (Charente), on one side fish and seals are deeply scratched, and snakes on the other (see fig. 3, 12, a and b); then, in the Pietta collection, there is a bone from the Gurdan's grotto (in Upper Garonne depot) with the clearly depicted head of antelope saiga (see fig. 3, 4), and in the Zurich Museum there are finds from the Schweitzersbild cave: a decorative bar with two excellent images of wild horses, a similar bar engraved with a reindeer and a piece of antler with a picture of a fish. But the most perfect images of animals in this way adorn some objects found in Kesslerloh, near Taingen. The aforementioned "grazing deer", extremely naturally and vividly depicted on a decorative bar (see Fig. 3, 11), kept in the Rozgarten Museum, in Constance, is exhibited in most French and English works on this subject even as the best work of its kind. However, a wild donkey on the decorative bar of the Shafgausen Museum (see Fig. 3, 10) is hardly inferior to the “grazing deer”; two heads of animals are especially good (see fig. 3, 5 and 7) on both sides of the agate plate, which is also one of the decorations of the Rozgarten museum.

A special category is stone slabs, on which images of animals are scratched, without distinction of top and bottom, they can only be separated from each other with difficulty. These include a snake plate from Lodgery-Bass, with three reindeers inscribed on it, stored in the Natural History Museum in Paris, and a wonderful limestone slab from Schweizsersbilda, located in the Zurich Museum; although on this slab the contour lines intersect randomly, however, on one side there are clearly images of a reindeer and two wild donkeys, and on the other two wild horses, a steppe donkey and an elephant-like animal (probably a mammoth). These stones, apparently, served as an exercise and the artists tested themselves on them before they began to decorate decorative bars and other works in this way.

Fig. 7. Tools of the oldest stone era with linear decorations. By Merck, Lart and Christie

Here the question naturally arises: have there been such drawings on the walls of the caves of the diluvial era? Probably, the most ancient wall images, which are still known to this day, are in the grotto of La Mute, which E. Rivière found. Here, a bison and an animal resembling a horse are engraved on the stone, and the contours are filled with ocher. However, it is impossible to decide whether these images belong to the later stone period or the earlier one. Anyway, it is in any case the most ancient of the engraved works of this kind available to the modern researcher.

Some objects of the diluvial cave epoch, however, are also equipped with linear ornaments. The transition from images of animals to other objects we see in Fig. 7, a: this is the spearhead from La Madeleine, stored in Saint-Germain. It is decorated with an image of a dangling animal or animal skin, and below with rosettes, which could be considered the oldest in the world, if it were possible to prove that this is really an image of vegetable rosettes, not sea stars, sea urchins or something like that. ; It should be noted that the latter assumption is more likely. Objects (Fig. 7, b and c) originate from Taingen and are kept in the Rozgarten Museum in Constance, while others are from Lodgeier-Bass and are located in the Museum of Saint-Germain-en-Leu. The harpoon (Fig. 7, b) is bordered with a ribbon-like ornament, which we also find on a similar object from the Dordogne; perhaps, it was executed in imitation of belts made from animal skins, which were twisted around the tips, when they were attached to wooden rods. A beautiful decoration on the tip (Fig. 7, c), consisting of longitudinal, alternating strips and elevations, appearing in the form of buttons, complicated by zigzag lines, repeats on the object in fig. 7, g, and wavelike - on the subject of fig. 7, d; in fig. 7, е, - in a pure form an ornament from wavy or snake-like lines, and a subject on fig. 7, well, it is decorated with a strip provided with teeth on both edges and resembling a snout-fish snout or a pattern on the back of some species of snakes. Even more remarkable are the ornaments made public by Piett and stored in his collection; these are concentric circles and spirals that do not have anything like themselves in the previously known diluvial ornamentation and are similar only to some of the ornaments from the end of the later Stone Age. It is remarkable, however, that in Wezher (VezHre) and on the Upper Rhine there are extremely complex decorative patterns of exactly the same kind, this testifies to the reciprocal internal connection of all such artistic attempts. But what can we say about the origin and meaning of these decorations? Whether the artists and lovers of those times looked at them only as a play of lines and buttons, just as we are currently watching, or did they understand these decorations as performed in the well-known style of reproducing objects around them, or, finally, for them were signs, symbols of spiritual representations, something like letters, or images in which religious content lurked? Perhaps the study of the restored by the new science of the decorative art of a somewhat closer time to us will throw some light on this prehistoric ornamentation.

All this art, although so tactile for us, but having, apparently, no beginning, no end, no cause, no effect, infinitely far away from us, obviously, developed and did not end in a continuation of any decade, and not even of a single human generation: it has been developing for a long time, perhaps for many centuries. We had the opportunity to note the main features of this development, but we would not be able to trace its gradual course even if we had submitted to the arguments of Piett, who was so gifted with such a rich imagination. Some of his attempts to distinguish between several local schools are more convincing. With all the similarities in the works of art of this epoch among themselves, the works found in the Dordogne are distinguished by a simple, crude character in comparison with the more natural and at the same time showing the richer imagination of the works of localities near the Pyrenees; the best drawings are from Taingen, with their immediate, subtly felt naturalness, again constitute a separate group.

But more sharply than all these differences, we are struck by the similarity of the essence of all these works of art, found from the Pyrenees to Lake Constance and to the Meuse, and maybe even further, to England and Moravia. We feel that they were created by people of the same spirit, in the whole of this vast area, hunting for animals, fishing, living in caves or in other secluded corners and brightening up their unpretentious, seemingly peaceful life by creating such works of art. Which tribe can be attributed to these people - a question not directly related to the history of art, which provides its solution to natural science, anthropology and ethnography. The work of the science of art is only to point out that for it all these works of art of a diluvial prehistoric era are extremely important, primarily as phenomena that undoubtedly existed, although without any direct connection with the art of the subsequent time. The fact is that these attempts at artistic creativity are clearer than any later prehistoric and even historical creations of art show what naturalness and truthfulness were achieved, despite all their simplicity, taken from the outside world images of primitive and completely naive humanity, and how well he developed an understanding style, despite the extreme scarcity of technical means - the natural consequence of a completely still infant worldview.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)