Introduction Architecture

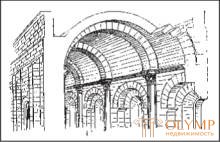

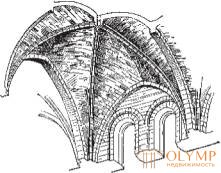

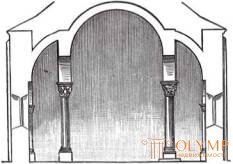

Fig. 148. Korobov vault with arches. By Degio and Bezold

France is a beautiful country, the nationality of which was formed from a happy fusion of the Celtic, Germanic and Romanesque races, at the time we considered it was divided, both by language and artistically, into two halves - the northern and the southern; the border between them was the river Loire. These two halves, differing sharply from one another, nevertheless, were already on the path to spiritual union. With regard to art, France at that time undoubtedly played a major role in Western Europe. North Spain, in the southern half of which flourished Moorish art (see t. 1, Fig. 653), was, with regard to the arts, nothing more than a province of southern France; in England, conquered in 1066 by the Normans, who were completely French by that time, art developed, which even in its individual forms was a branch of Norman-North French art. Both great powers of the medieval world — chivalry and monasticism — flourished in it. In France, the fire of enthusiasm to win the Holy Land from the infidels was inflated all over earlier and more successfully. The capital of France has become the main center of scholasticism, turned gray in the service of the Church and tried to rely in its constructions on Aristotle's medieval philosophy, which the dialectical house of cards designed by itself was skillful and in keeping with its goals. In France, however, a movement arose, which resulted in the renewal of the whole monastic life, which until that time did not go beyond the framework indicated by St. Benedict of Nursia. Monasteries were still the main centers of artistic life. Of particular importance in the history of art are the monastic orders of Clunyans and Cistercians, whose birthplace was Burgundy (Cluny and Sito, or the Cistercium).

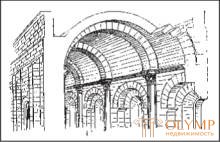

Fig. 149. The capital of the column from choral bypass in the church of Sts. Trophime in Arles. According to Bezold

Thanks to them, the Burgundian architecture got a completely new character; but besides Burgundy and other provinces of modern France each went their own way.

In general, hardly any other country Romanesque architecture has evolved as versatile as in France. The influx of elements from the Hellenistic, Syrian, and Asia Minor East into this architecture, traveling as often through Marseille as through Ravenna and Milan, and in some cases through Rome, ended in the preceding era. What now developed from these elements was, both in the north and in the south of France, already French property; especially in the north, a vivid artistic feeling immediately began to independently process the Romanesque circular arch style into a new, national architectural style.

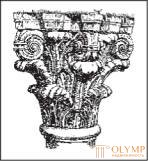

Fig. 150. Simple cross vault. From drawing

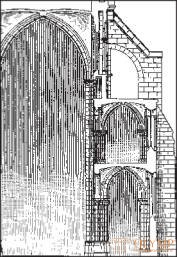

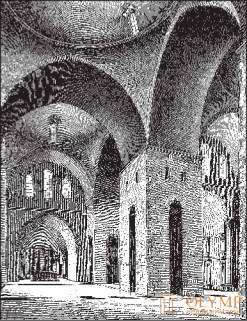

Whereas the architecture in the south of France, where vaulted coverings were used primarily for the archway (fig. 148) and the dome, was also almost a continuation of ancient art at that time, and even tried to retain its individual forms (fig. 149), after a brief period of reflection, correctly understanding the essence of the cross vault (Fig. 150), went straight to that constructive system, which is called Gothic. Therefore, to consider the birth and growth of the Gothic style (Fig. 151) can not particularly from the history of the Romanesque style in France. Some elements of the Gothic style, such as, for example, the lancet arch, a vault with ribs (Fig. 152), a complex pillar (a column decorated with semi-columns or three-quarter longitudinal sections of the columns), circular bypass in the choir and natural foliage pattern borrowed from the local flora, appear one after another in various Romanesque buildings. This development ends first of all on the banks of the Seine, in the heart of most of the German-Frankish Northern France, a point that was soon to become the heart of all of France, and at the same time in neighboring Picardy; but here, in the birthplace of the real Gothic, the Romanesque style received an insignificant development, while in the rest of France, in spite of all the elements of the transitional style, it reached a flourishing in its pure form.

It’s not easy to make a complete and correct picture of the most perfect works of Romanesque architecture in France, because most of its monuments, and, moreover, the most beautiful and significant, have either died or come down to us in the form of picturesque ruins. True, thanks to diligent scientific research, many of these monuments became the property of history. In France, researchers such as Kisheri, de Lasteyri, Corwaye and Anlar worked on the development of new questions or on a set of data obtained earlier, following Viollet de Duc and de Comon, and in Germany, after Schnazé, Otte and Lubcke, especially von Degio, von Bezold, Borrmann, Neuwirth, Cornelius Gurlitt and Witting.

Fig. 151. Early gothic system. A cross-section of the longitudinal part of the Noyon Cathedral. By Degio and Bezold

Among the dead architectural monuments belong to the bottom of the church in Central France, which at one time were ranked among the largest and most beautiful buildings in Europe - the church of St. Martina on Tour, which was considered to be one of the main works of Western architecture back in the pre-Carolingian era, and a monastery church in Cluny, at least from Ottonian time, attributed to the most wonderful creatures of architecture. Both of these churches already had curious features in architectural and historical terms when they were rebuilt in the era of mature romance. Church of sv. Martina after the fire of 997 was restored in the form of a cruciform five-nave basilica with a flat covering, with a single-nave transept, but with a double semicircular choral circuit and a crown of chapels. The latter architectural motive became later typical of French church architecture. In the 12th century, the restructuring of this church was carried out with the aim of its overlap with arches. Five towers, of which two survived, the only remnants of this magnificent building, adorned the center of the cross, the southern and northern sides of the transept and the western facade. The original church of the Cluny Abbey was rebuilt into another, consecrated in 981 (see kn. 2, II, 3); and we should consider it as a basilica with a flat covering and columns. Its peculiarity consisted in the arrangement of the choir: it received an ending straight-line quadrangle choir with two rectangular chapels that played the role of side choirs, and, in addition, five apses, of which three were in three choir choirs and one each at the ends of the transept; on the western side two large towers towered above the narthex. We will see that this successful plan, in the creation of which, perhaps, the Lombardman William of Ivreis took part, who built the famous column basilica with a rounded choir in Dijon around 1000, was widely used and imitated itself in northern France, Germany and Italy The third Cluny Church, begun in 1089 and consecrated in 1095 - a monument to the highest prosperity of the Cluny Order - sacrificed its old simplicity in favor of greater monumentality and pomp. True, because of this, she, as Degio proved, did not have such a wide influence on the church architecture of the epoch as the second church, but it became an exemplary building for the entire late 12th century Burgundian school. Her five-nave longitudinal hull was cut by two single-nave transepts; the semicircular choir with an internal circuit and the crown of the chapel was borrowed from the church of Sts. Martina on Tour; the middle nave was covered by a box-shaped vault with spring-loaded arches, the low side aisles - by the cross vaults. From Corinthian fluted pilasters, formed by the projections of the main pillars, high column bunches (complex pillars), supporting the arch arches of the vaulted roof, rose. Under the windows of the middle nave stretched, in imitation of the emporic side aisles, the so-called gallery of triforia, whose arches, like the arches of the windows, were semi-circular; but the main arcades of the longitudinal hull were already pointed. "The later victories of the Gothic," said Degio, "were already half won in Cluny."

Fig. 152. Cross vault with ribs. By Degio and Bezold

In southern France, the Romanesque architecture of which was thoroughly investigated by Revual, church architecture at that time developed, as mentioned above, in close dependence on ancient forms, moving away from them only step by step. In various places in Southern France, many architectural samples were preserved in the magnificent Roman-Hellenistic buildings, which were abundant outside with Corinthian columns and pilasters and often covered inside with box-shaped vaults. It is enough to recall at least the temple of the princes Guy and Lucius (Maison Caree) in Nimes, the theater and the arch of Tiberius in Orange (vol. 1, fig. 497), the amphitheaters in Arles and Nimes.

From the South French basil with a flat surface only the Church of Sts. Aphrodisia in Beziers, whose facade, decorated with arcades, resembles similarly decorated Pizan and Lucca facades (see Fig. 138). In southern France, as well as in the Christian East, it was already quite early to try to solve the problem of replacing wooden fireproof ceilings with stone vaults. Influenced by Rome and the East, a box dome came into use here, which, however, often supplanted the dome system, and just as it happened in the East, these experiments of the vaulted roof lost the taste for basilic architecture, the essence of which is more compared to with the height of the side walls, the height of the middle nave, illuminated by holes in its walls. The South French churches consist, with rare exceptions, either from one nave, or from three naves of approximately the same height (churches of the hall system), or they are buildings of the central type, quite often ascending directly to the eastern patterns.

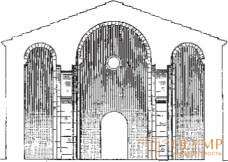

Fig. 153. Plan of the cathedral in Orange. According to Bezold

The single-nave, overlaid churches in their purest form do not have a transept; in this case, in the altar space in front of the semi-circular apse, the floor is usually elevated or the floor of this space is made higher and even often turns into a dome. Korobov vault of the nave, mostly pointed (lancet), was cut by arches, which in Provence rely on antique-style pilasters, and further to the west, in Languedoc and Aquitaine, into semi-columns. Of the buildings of this kind to the second half of the XI century is the cathedral in Avignon; its octahedral domed tower above the altar space is decorated outside with Corinthian columns, and the ancient forms in the portal decoration (fluted Corinthian columns and a cornice bearing the meander motif above the three-member entablame) are so clean as if they were made in late-Roman architecture. The extensive and beautiful inside the cathedral in Orange, similar in plan to Avignon (fig. 153), belongs in its essential parts to the 12th century. The Toulouse Cathedral, grandiose in its proportions, built at the beginning of the XIII century, therefore, in the era of transitional style domination, was already blocked by the cross vaults. C. Gurlitt said about him: "We do not know in France of a single ancient vaulted building at least about the same efficiency as the Cathedral of Toulouse."

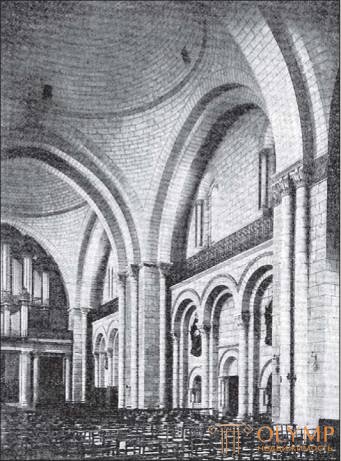

Fig. 154. The interior of Angouleme Cathedral. According to Gurlitt

Strictly speaking, a number of domed churches in South-Western France are also referred to as single-nave churches, the significance of which Felix de Verneuil first drew attention to, and in Germany Felix Witting. In these churches, the massive pilasters, strongly protruding inward, carry on themselves, instead of sections of the box arch, separated from one another by spring arches, along a flat dome over each square of the plan; in earlier churches, the pandantes of these domes are still folded in a primitive way, through the release of overlapping rows of stone. In its simplest form, this type of church architecture is before us in the Cagorsky Cathedral (about 1100), which does not have a transept. The most magnificent single-nave, but equipped with transepts, churches of this kind are the Angouleme Cathedral (fig. 154) and the Fontevro Abbey church, the buildings of the first half of the 12th century. In both churches, the rounded choir is provided with a crown of chapels. But Angouleme Cathedral is notable for the greater luxury of the sculptural ornamentation of the facades and the beautifully dissected towers over the wings of the transept, and the church of the Abbey of Fontevro has a magnificent colonnade of detours inside its choir. In its highest development, this Romanesque dome architecture of Aquitaine is in the central part of the majestic, frequently mentioned church of Sts. Frona in Perigueux (Fig. 155), built after 1120. This is a five-domed church with a plan in the shape of a Greek cross. Its close relationship with the Eastern churches and the Venetian Cathedral of St.. Mark is so striking that one cannot deny its connection with Byzantine patterns. St. Fron (Saint-Fron) and the outside had the appearance of a Byzantine domed temple, until its five domes of the same height were covered by one common roof at a later time. It is worthy, however, of attention, that the main arches are under the domes, but only they are alone, already pointed; the pandanteus of the domes are still formed by issuing rows of stone forward one above the other. Inside the church there are no marble and mosaic decorations, but with a modest decoration of the walls with deaf arcades of the Corinthian character, it gives the impression of an exceptionally noble simplicity of its location and harmonious proportions. The spectacular appearance of the building increases its luxuriously dissected tower, topped with a round superstructure, decorated with columns, which resembles the upper tier of the Julius Tomb near San Remi.

Fig. 155. The interior of the church of sv. Fron in Perigueux. Lubka

Assuming that domed buildings of this kind arose under the influence of the eastern ones, and towers under the influence of western-antique designs, one should not detract from the independence of their builders who freely processed borrowed architectural motifs.

Even more common than the single-nave churches were the three-nave churches in the whole of southern France, which were covered with boxed arches. True, in such churches all three naves are only rarely of exactly the same height. A distinctive feature of these churches is that the upper walls of the semi-dark middle nave are either not at all, or they are not high enough to make windows comfortable in them. The hall system, which allows for a different location of the choir, is most clearly displayed in those churches in which the aisles are not divided into two floors and do not have empores, but in which there are three parallel vaulted vaults, although dissected by the arches, cover all three naves in the longitudinal direction . To the oldest churches of this kind belong churches of sv. Fees in Leran (Fig. 156) and of sv. Martina (St. Martin d'Ainay) in Lyon. The circular arc style was consistently held in the Leisterpian church, which has unusually narrow side aisles; church of sv. St. Nicholas in Sivre, whose facade is decorated with fantastic fantastical sculptures, is already covered with pointed arched vaults; finally the church of sv. Nazariya in Carcassonne is a noble hall structure, the middle nave of which is covered with pointed doors, and the side naves - with circled duct vaults.

Fig. 156. A cross-section of the church of Sts. Fee for leran. By Reeual

Fig. 157. Cross-section of the church in Granson, in Switzerland. By Rana

In some respects, we see the transition to the Gothic construction in churches, one-story side naves of which are covered with duct half-arches, opening like supporting arches (arches), in the middle nave, covered with a full duct arch. This circular-arched system appears, for example, in the Granson church in Switzerland (fig. 157), while the beautiful church in Fonfruad, which has graceful pointed arches, belongs to a transitional style.

There are also such churches of the hall system, in which the main nave is covered with a crown, and the side - with the cross vaults; среди них особенно замечательны церковь в Сен-Савэне, на непомерно высокие колонны которой, снабженные уродливыми базами, можно смотреть как на круглые столбы, и церковь Богоматери Великой (Notre-Dame la Grande) в Пуатье, в которой боковые нефы столь низки, что ее можно причислить к церквам зальной системы только по лишенным окон стенам среднего нефа; она знаменита также фантастическими скульптурными украшениями своих фасадов.

Наконец, некоторые трехнефные церкви зальной системы, очень красивые и гармоничные внутри, имеют сводчатое покрытие в форме куполообразных крестовых сводов, что дает право, например Дегио, причислять их к разряду однонефных купольных церквей типа Ангулемского собора или церкви Фонтевроского аббатства. Первым зданием этого рода был собор в Анжере, на правом берегу Луары. Главный памятник подобной архитектуры к югу от Луары — заложенный в 1161 г. собор св. Петра в Пуатье, в котором, по словам Дегио, «куполообразный крестовый свод с нервюрами и древнефранцузская зальная система образуют одно из самых удачных сочетаний». Куполообразному крестовому своду соответствует и форма столбов. Переход к готике виден здесь с особенной ясностью.

Всем этим церквам зальной системы с одноэтажными боковыми нефами должны быть противопоставлены перекрытые коробовыми сводами церкви той же системы с эмпорами — здания, в которых нижние этажи боковых нефов имеют крестовые своды, а верхние открываются в средний неф коробовыми полусводами. Хор в таких церквах чаще всего состоит из полукруглого обхода на колоннах, с венцом капелл; над средокрестием поднимается высокий восьмигранный свод в виде купола (так называемый монастырский, сомкнутый, или котельный свод). Арки — почти всегда еще полуциркульные, а над колоннами хорового обхода — повышенные; их орнаментальные формы — коринфского характера.

Как на типичное сооружение в этом роде можно указать на церковь Богоматери (Notre-Dame-du-Port) в Клермон-Ферране, красиво расположенной столице Оверни. Но самое замечательное сооружение этого овернского стиля находится не в самой Оверни, а дальше на юго-западе, в Тулузе, старинной, славившейся ученостью столице Лангедока. Church of sv. Сернена (или св. Сатурнина) в Тулузе, главные части которой принадлежат XII столетию, — один из самых величественных памятников романской архитектуры. По своему плану, с пятинефным продольным корпусом, который пересечен трехнефным трансептом, с венцом капелл и ясно выраженным средокрестием, эта церковь как бы восходит по прямой линии к церкви св. Мартина в Туре. Ее архитектура, как мы сказали, овернская. Подпружным аркам коробового свода соответствуют полуколонны столбов. Эмпоры боковых нефов открываются полуциркульными арками, имеющими такую же ширину, как и лежащие под ними главные арки, но разделенными каждая на две грациозные арочки. Продольный корпус освещен окнами, проделанными в стенах крайних боковых нефов. Интерьер церкви, хотя и освещен недостаточно сильно, прельщает взоры своим красивым расчленением, а царствующий в нем таинственный полумрак возбуждает в душе мистический трепет.

It means that we’ve seen the whole constructive system. Step by Step in Nevers, it is so low that there is still space for the windows above them. Doric capitals of the choral bypass

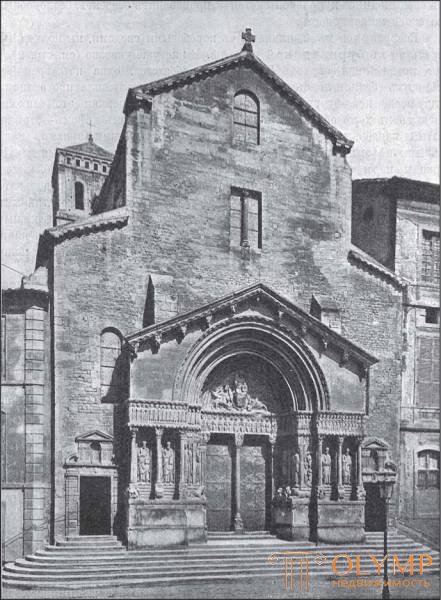

Basilicas with Korobov vaults in Provence and Languedoc, where the middle aisles are not used to seeing freely outstanding, had a heavy thickening of the pillars and a narrowing of small naves, which were overlapped by the koromovy semi-arches. Church of sv. Trophime in Arles and the Church of Sts. Paul in Trois-Chateau, built in the XII century, exhibits all the features of this style: the first has an archery, the second is a circular-arched duct vaults. The oldest cross vaults with ribs are located in the crypt of the ruins of the church of Saint-Gilles (St. Egidius) in Provence. Proto-renaissance of the facades of the churches of St. Trophime (fig. 158) and sv. Aegis, luxuriously decorated with sculptures, resembles the Florentine church of San Miniato (see Fig. 137).

Finally, two domed churches of a special kind should be counted among the vaulted basilicas of southern France. The first of these, the Church of Our Lady at Le Puy, is a three-nave basilica with three choir straight in plan and original T-shaped columns of the middle cross, decorated with double columns of oriental character, and interconnected elevated arches. The dome above its midcross is spherical, most of the domes of the longitudinal body are octahedral. The second church, Saint-Hiller-le-Grand (St. Gilaria) in Poitiers, one of the most revered sanctuaries in France, has as many as seven naves. Her choral bypass is endowed with a crown of numerous chapels. The side aisles are covered with transversely laid double box walls, and the square compartments of the main nave are domed. In both churches, the light falling through the windows in the upper walls of the middle nave, in conjunction with the dome system, produces an effect unmatched in its picturesqueness.

Returning to the basilicas with baskets, we are approaching the Burgundian school. It has already been pointed out above that the later church of the Cluny Abbey, one of the grandest basilic with basilic vaults, served as a prototype for the whole Novoburgund school. The typical churches of this school have a column bypass in the choir, an arched box-shaped vault dissected by spring arches above the main aisle, and a cross vault above the small aisles, decorative arcades under the windows of the middle nave instead of empores. In the design prevails everywhere lancet arch; we find it in the arcades of the longitudinal hull. Semicircular arch is more common in decorative forms; by the way, it runs out of windows. At the same time, the individual forms of these buildings are strikingly close to the ancient ones; for example, the pillars consist of fluted Corinthian pilasters, resembling the forms of the Renaissance.

Fig. 158. The facade of the church of sv. Trophime in Arles. With photos of Girodon

In the south of Burgundy, which, like the Cluny itself, entirely belongs to the southern half of France, the Lyon and Viennese cathedrals present many deviations from the pure Cluny style. The main churches of this kind are in the north of Burgundy; but although they belong to the northern half of France, they should not be considered separately from the churches of Southern Burgundy. The most characteristic monuments of the later Cluynian style are the church in Pare-le-Moniale and the cathedral in Atene. Both buildings belong to the XII century. In the first of these, in the dismemberment of the walls, the Romanesque half-columns alternate with ancient pilasters. In the Aenean Cathedral, the dismemberment of the walls in the ancient spirit by pilasters was carried out very consistently. In connection with these churches, we must also point here to two more Northern Burgundian churches, the geographical position of which is already manifested in the fact that their middle naves are blocked not by chests but by cross vaults. This is, firstly, a beautiful cathedral in Langres, with the still ancient dismemberment of the walls through pilasters, and, secondly, the Church of the Vessels Abbey, similar in architecture to these churches, which differs, with somewhat compressed proportions inside, with an amazingly beautiful portal. These two churches in many ways already represent the transition to the Gothic.

On the border of Northern Burgundy is also Sito - the birthplace of the Cistercian Order, whose architecture spread everywhere wherever the sermon of the Order's brethren penetrated. Sito Abbey was founded in 1098 as a cloister filial in relation to Cluny Abbey. From Sieve of sv. Bernard Klervosky preached a second crusade; from here he sent his envoys all over the world, and here the building principles of the Cistercian order were worked out. His slogan was simplicity and severity. The Cistercian churches returned to straight-ended choirs, equipped with small abscies, to the choirs of the old Cluny churches (see figs. 152 and 153). They are also related to the latter by the absence of a crypt under the choir; besides, they did not have towers, empor, deaf arcades and fake galleries (triphoria) over the side naves. On the west side was a low open porch. The ornamental forms were limited to the most necessary, but were carried out carefully, in noble and simple proportions.

Unfortunately, the first Burgundian buildings of this style did not reach us, but that they also had a lancet vault over the middle nave, proves, for example, the small Cistercian church in Fontenay, in Burgundy, belonging, as it should be, to the first half of the XII century. As the best example of the French Cistercian architectural style of the second half of the XII century, it should point to the church at Pontinha Abbey, on the border of Champagne. The surviving church is a new building from 1150, which originally had a direct end to the choir and received its current choir tour with the crown of polygonal chapels in 1180. It is dominated by a cross vault with a developed system of ribs everywhere, abutting on half-columns of pillars; the arched arch also prevails, even in the windows, which in the North French early Gothic still often end in a semicircular arc. But, on the other hand, it still has no supporting arches and the windows do not occupy the entire surface of the wall. Indeed, the church in Pontigny is a transitional stage from the Romanesque to the Gothic. All the same, whether we call this Burgundian style late Roman, early Gothic or transitional, is not the name; only the term “rudimentary gothic”, proposed to refer to this style, cannot be considered quite successful.

Along with all the church buildings, both in the south and in the north of France, with which we got acquainted, there are some civilian buildings that belong to our time (in Cluny and Caussade); but the closest consideration of them would lead us away.

Looking once more into the whole area of the Romanesque architecture of southern France, we are convinced of how little this rich, noble in form and expressive art contains what is called the Romanesque style in Germany. The connection of this art with the ancient one is preserved both as a whole and in particular. At the same time, with regard to Southern France, as well as with respect to Italy, we consider it more correct to speak of the continuous continuity of the ancient traditions, which have now reached new heyday, than of their revival. Although the Romanesque art of southern France is separated from Roman art for centuries of barbaric understanding of ancient forms, however, in this transitional period, the only desire was to create further on an ancient basis. Not survived only intermediate steps. That new, medieval, which, along with the old forms, peeps in the southern French architecture of the time in question, flowed into it from the north of France, saturated with German elements.

Plastics

In the Romanesque period, plasticity again returned to the monumental tasks that, in the early Middle Ages, under the influence of the early Christian and Byzantine views on art, were thrown by it; Moreover, medieval plasticity, constantly rising from modest buds to the fullness, richness and splendor of sculptural decoration of gigantic Gothic cathedrals, understood these tasks in some respects even wider than classical antiquity. While antique plastics sought out monumental grandeur and found it to ensure that the free surfaces of the building were reserved for it, the facade sculpture of the mature Middle Ages, which drew its content mainly from worship and mysteries, merged to such an extent with the individual plates that were part of the outer the decoration of the building, that the style of not only its compositions, but also individual figures was often determined by the shape of the stone, which, in turn, depended on its architectural purpose.

The medieval sculpture of facades and portals, at the time of its highest development, covered huge buildings with thousands of luxurious, artfully placed statues to their full height, both standing and seated, many bas-reliefs and high-reliefs, closely related to architectural elements, is a magnificent and original western industry artistic activities. The latter, in particular, should not be overlooked when it is assumed that the forms of this sculpture are still echoing in their particular Greco-Roman art and that at the same time it in many cases, especially where there was a lack of Greco-Roman patterns, resorted to through the East Christian , predominantly Byzantine applied art, diligently executed works of which were common and highly valued throughout the West. From them, the medieval monumental plasticity borrowed many types and individual motifs of the compositions, for which she studied the dressing of hair and the drapery styling. But when translating these parts to a larger scale, it went on its own, in different countries in different ways; in its general character, this art is directly opposite to Byzantine art, in which monumental plastics never existed. The transition of the antique style of monumental sculpture to medieval is nowhere to be seen with such clarity as in France. The Romanesque plastic facade of the south of France follows the successors of the antique direction; in the north of France, a new monumental style of sculpture was formed along with the Gothic. In addition to the talented French researchers Viollet de Duc, Emeric-David A. de Bodot, L. Courageot, L. Gons and A. Marignan, German scientists V. Lubcke, Paul Klemen, V. Feoger and others took part in studying the development of medieval sculpture. Fege turned this study to a completely new direction, and in our further exposition we will adhere in the main features of the conclusions reached by this scientist.

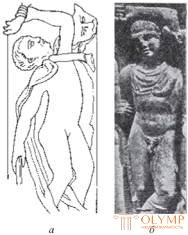

Fig. 159. The Evangelist John. Statue at the portal of the church of sv. Trophime in Arles. According to Föge

The rudiments of the monumental style of medieval sculpture should be sought in Provence; it was here, where there was no lack of plastic works of the late Roman and early Christian era, that these rudiments naturally surround late antique sculpture. The most important works has Arles. Statues of the apostles in the north wing of the gallery cloister at the church of St.. Trophimes belonging to the beginning of the XI century, still belong to the Late Antique style. This is proved by the free performance of hair and drapery styling. Then worthy of attention are the sculptures of the portal of the same church, made probably around 1150, although they are often referred to a later time. The tympanum depicts the Savior sitting on the throne in the middle of the symbols of the evangelists; On the architrave of the doors - 12 seated apostles. On the walls near the portal are placed on both sides large, life-size statues of the apostles (Fig. 159) and saints, made of high relief; above them is a relief frieze with images of biblical scenes. Just as the architectural forms of this portal have an antique character, so its sculpture bears an antique imprint on itself. The male figure on the socle is apparently copied from the figure of a naked young man in a Roman sarcophagus, in the Museum of Arles (Fig. 160). A comparison of the figures of the apostles in the gallery of the cloister with the apostles on the facade shows how medieval art in some cases instinctively returned to the archaism of ancient Greek art. The bukli and strands of hair are becoming sketchy again, the styling of draperies is smaller, more beautiful and more refined.

Such plastic decorations cover the three portals of the church of the neighboring St. Gilles Abbey, the facade of which is completely in the character of the facades of the Renaissance. And here on the tympanum of the middle portal is depicted Christ between the four symbols of the evangelists, on the tympanum of the left portal - the Mother of God sitting on the throne, on the tympanum of the right portal - Crucifixion. Luxurious plastic decorations of the walls are connected into one whole by columns, the capitals of which are partly ornamented by figures of animals and angels. Feuge cited compelling evidence that the facade of the Saint-Housing Church was built later than the facade of the Arles church of Sts. Trophime Both of them serve as a brilliant testimony to the power achieved by Provencal sculpture in the 12th century.

Fig. 160. The figure of the porch in the church of St.. Trophime in Arles (a) and a figure on the same antique sarcophagus in the Museum of Arles (b). According to Föge

In Languedoc, especially in Toulouse and Moissac, the parallel development of monumental plastics, which here, however, from the very beginning further deviated from the ancient tradition and allows you to see more clearly the Byzantine influence in particular, can be traced from 1100 From the works of the early school in Toulouse, the sculptures adorning the church of Sts. Petra in Moissac. The most antique character are the figures of saints on the pillars. Then noteworthy are the marble sculptures in the choral bypass of the church of Sts. Cernin in Toulouse; The image of the Savior on the throne, surrounded by an oval nimbus, especially characterizes the lower relief and the more barbaric language of the forms, which distinguish the early Toulouse school from the Provençal one. The folds on the tight-fitting clothes are shown quite schematically. “Everywhere,” Föge said, “the same ornamental face pattern is repeated: eyes circled like glasses, long straight nose with disfigured nostrils, mostly tiny ears, puffy cheeks, sketchy, braided hair” .

From the early school of Toulouse came the later, the main works of which are sculptures of the southern portal of the church of Sts. Cernin in Toulouse, the western portal of the church of Sts. Petra in Moissac and the porch of the same church. In the vestibule of the Moissac church, under relief friezes depicting episodes of the Savior’s youth, large allegorical figures of “virtues” are placed on one side, and “mortal sins” and expected punishments for them on the other. Above the door is Christ sitting on the throne with four evangelists and twenty-four apocalyptic elders; on the doorposts are the apostles Peter and Paul, two prophets and

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)