India, bounded from the north by the highest mountain range in the world with its snowy summits reaching the clouds, from the northwest by the Indus valley, from the northeast by the region of Brahmaputra, the greatest of the tributaries of the sacred Ganges, from the other sides washed by the dark ocean waters, is a luxurious tropical world, in which richly cultivated areas alternate with impassable primeval forests, swamps covered with bamboo, are replaced by an impassable jungle thicket, plateaus - river valleys. The bearer of the historical culture of ancient India was one related to us Aryan tribe, which, having appeared from the north for 2000 years BC. e., penetrated to the Indus, and then to the Ganges, gradually, though not completely, conquered the natives and spread their culture, powerful and fruitful, to the whole peninsula. It was a tribe that had already lived its stone and bronze centuries, had become fully acquainted with the use of metals, had fully learned agriculture and cattle breeding, but had exchanged its northern homeland for the sultry south; it was the people of priests and warriors, whose castes were sharply separated from the two lower castes, from the workers and servants, the people of prophets and poets, who inherited artistic riches from the ancestors writing and spelled out their beliefs, piety, law and customs in sacred songs.

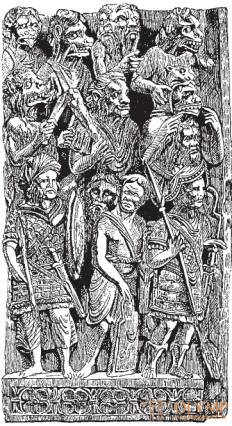

Fig. 555. The host of the demons of Mary. Gandhara relief. According to Grunwedel

After the time of the addition of the hymns of the Ved, there followed the time of the appearance of the heroic poems of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, which should be attributed to 1000 BC e. In these poems, the ancient Brahman teachings about the gods were prepared on the basis of the pantheistic general ideas of the Ved era, which eventually led to the recognition of three great, main deities: Brahma as a creator, Vishnu as a guardian and Shiva as a destroyer, and in individual states of this huge country, primacy passed on to to one, then to another of these deities, with his entire retinue of countless minor gods and demigods. About 500 BC. e. The reformer of the Brahmin religion was Gautam Siddgart of the Sakyamuni clan, as Buddha, that is, "enlightened." The story of his life is full of legends. It is only credible that he "moved to Nirvana", that is, he died in 477 BC. e. After Ashoka, king of the powerful Hindu state of Magada, in 250 AD e. elevated the teachings of the Buddha to the degree of state religion, it was widely distributed and, having won in its swift, victorious march a large part of South, Middle and East Asia, became the first religion in the world. The wisdom of the Buddhists was probably the basis of the wisdom of the Brahmins. Pantheism and faith in the transmigration of souls remained completely inviolable, but numerous saints took the place of the gods; self-flagellation was replaced by a distance from the world to the monasteries, Nirvana received the value of the highest blissful state, the end point of all the wanderings of the soul, for which in this state eternity comes without dreams and worries. Of course, in the popular Buddhist religion, the Buddha himself soon became a deity. Lassen said: "The nature of Buddhism suggests that initially he was a stranger to all mythology; but since his followers were Hindus, who had extensive teachings about gods, he had to remain free from the influence of this doctrine for a short time." The buddhas themselves multiplied. True buddhas were born even before Gautama, they could have been born after him. These minor buddhas are called “bodhisattvas,” and every pious person can strive to reappear in the form of a bodhisattva after his death. Thus, a host of hordes of minor gods and demonic demigods joined the host of celestials, who often personify abstract concepts like the goddess of beauty, Sri (Shiri).

Meanwhile, Buddhism was asserted more and more in Ceylon, in Indochina, in the Sunda Islands, in Tibet, China and Japan, in India itself since the 6th century BC. n e. We are absorbing the old polytheistic folk religion, which has gained predominance as the Novobrakhmanism. Already from the VII century. Buddhist monuments in West India are found less and less, and in the VIII century. almost completely disappear. Only a few of them belong to the XI century.

Novobrahmanism, the former, like Buddhism, not only religious but also artistic power, was in full bloom when Islam began, at the end of the eleventh century, to conquer India itself. Millions of Hindus converted to Mohammedanism, and numerous mosques appeared near the temples of Vishnu and Shiva. However, in the history of Indian art, only artistic works of Brahmanism and Buddhism are subject to consideration.

Despite all the good faith, with which such researchers as Ferguson, Burgess, Kenningham, Smith, Kohl, Le Bon, Mendron, Bühler and Grunwedel studied and described the numerous surviving monuments of Indian art, its history is just beginning to receive a scientific formulation. True, we can already distinguish between local features that can be attributed to various influences; but we know very little about the internal progressive development of Indian art. Grunwedel, whose views we share in many cases, even claimed that he sees in Indian art only a movement backwards.

Since the surviving ancient Indian works of art are almost exclusively monuments of monumental religious art, we can assume that the thousand-year old Brahmin art (up to 250 BC) was followed by the thousand-year Buddhist (and up to 750 AD), and behind him again the thousand-year Novrahmanskoye. From the ancient Brahmin era, however, no Indian artistic monuments survived. The oldest of them belong to the time of King Ashoka and the recognition of Buddhism as the state religion. But it would be a mistake to conclude from this that Ancient Brahman art did not exist at all. The traceless disappearance of the works of this art, distinguished by the richness of colors and sung in the great Indian heroic poems, is explained by the fragility of the materials used by Indian architecture and sculpture; they were predominantly wood, and as proved by Zemper, plastered bricks and broken clay. Of course, in the hot climate of India, neither one nor the other could survive after several centuries.

Thus, the history of Indian art monuments begins approximately only from 250 BC. e. - from the time when Indian art passed to stone buildings. Obviously, Indian stone architecture arose due to the religiousness of King Ashoka, who wanted to perpetuate numerous buildings erected by him in honor of the Buddha. In this transition to stone buildings, some of their forms were borrowed from the architecture of the great neighboring Western states, which was quite natural, since these states had already been in contact with India for centuries. First of all, it is necessary to point out some forms borrowed from Asia Minor through the medium of Persia, such as the bell-shaped capitals of the columns, similar to an overturned flower cup, animal figures above the capitals, supporting the architrave (fig. 556 and fig. 249), winged animals and fantastic creatures scattered throughout the ornaments, and so-called palmettic and lotus ornaments, stylized in the spirit of Western art. Then it is necessary to point out some somewhat later statues found in Mathur, in the upper Ganges region, even completely Greek in appearance (see fig. 554). In the art of the northwestern borderland of India, in the art of Gandhara in the Swat region, during the first centuries AD e. the Greco-Roman element to the extent prevails in the totality of artistic forms with a purely Buddhist content that all connoisseurs of the history of art come to wonder (see. Fig. 553).

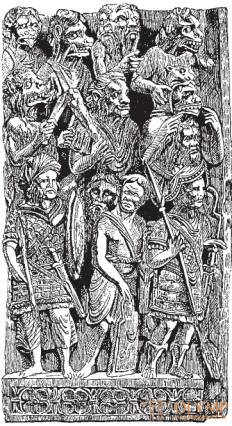

Fig. 556. Relief of the right pilaster of the eastern gate in Sanchi. According to Grunwedel

The question is, however, whether these facts are enough to combine, as was the case with Kenningham, all the Buddhist art of India into one Persian-Indian and Greek-Indian, so that there is no place for national Indian art at all. ? The answer to this question, in our opinion, can only be negative. First of all, with regard to the so-called Persian-Indian art, in its ornamentation from the very beginning we find, next to the forms borrowed, the forms of undoubtedly local animals and plants; besides - and this is even more important! - all Indian architecture and sculpting in its forms and content is not blindly adhered to Persian designs. If the remains of the oldest wooden works of art of India were preserved, the question would have been put, quite possibly, quite differently. Further, with regard to the Greco-Buddhist art of India, then, except for the mentioned monuments of Matura, the area of its distribution was limited only to the extreme north-west of present-day India, which initially no one actually counted as India. The art of Gandhara should be recognized not as one of the sources of Indian art, but as a Greco-Roman scion. Grunwedel, who maintained the English classification in general, said: “While in the ancient Persian-Indian group the national-Indian element constitutes the main core and is further developed on Indian soil, the Gandhara school assimilates foreign, ancient forms. Later, this school influenced Indian art, but it remained itself isolated and was kept most firmly in the religious art of the northern non-Indian school. " The so-called Persian-Indian art stands for us to the fore as the ancient Buddhist art of India. The preserved Buddhist monuments of this country are of a threefold kind: commemorative pillars, stupas and cave structures.

Fig. 557. The capital of the victory column in Sankis. According to Ferguson

Let's stop first of all on the memorial pillars, supplied with inscriptions (stambha, lat). At the top of their slender fusts, we enter the aforementioned bell-shaped Persian capital, which is often above and below separated from other parts of the monument by embossed pearls and cords; sometimes on the trunk, sometimes on the pillar abacus, over the capitals, we find a fully developed palmettic or lotus ornament borrowed from Western art; but right there, on the upper platform of the monument, we find symbolic religious sculptures of a purely Indian character, for example, a wheel with knitting needles, or an elephant (Fig. 557), most often the beloved lion figure in all of Asia. Monuments of this kind, dating back to the time of King Ashoka, partly destroyed, partly transferred from one place to another, have reached us quite a lot in the whole Ganges valley, for example, in Delhi, Allagabad, Tirgut and Sankis. Such a pillar stands in front of the famous cave temple in Carly, near Bombay. Images of such monuments are found in the reliefs of the time of Ashoka. From the harmony of these pillars, which differs especially in Allagabad, it can be concluded that their forefathers were tree trunks that turned into masts.

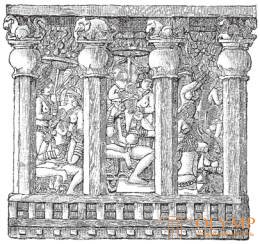

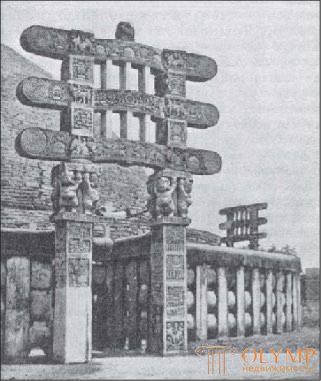

In a large number of preserved huge dome-shaped monuments of the Buddha, erected in remembrance of his earthly journey or to store his relics. These structures, called stupas (English topes), belong to the most peculiar works of Indian national art. If the remains of the Buddha are placed in them, then they are primarily called dagob (dhatugharba, dagoba). On the quadrangle terrace there is a massive dome, built of small stones, resembling a water bubble in its shape. This form symbolically expresses the fragility of all earthly things. On the flattened top of the dome is a superstructure, which serves as a reminder of the sacred fig tree, under which the Buddha received revelations. The wide base of the building is usually surrounded by a stone wall with high entrance gates, such as triumphal gates and with abundant sculptural decorations. These stone fences (English railings) with their gates, which preserved the imprint of the style of the oldest buildings of this genus, belong to the most important, and often to the most brilliant monuments of Indian art. In some places, in various regions of India, stupas have been preserved with or without their stone fences, in places, only stone fences, without stupas or with their ruins, survived. From 25 to 30 stupas, of which the stupa in Sanchi (fig. 558) is the most famous, is located not far from Bilsa, at the northern foot of the Vindgiansky mountain range, in the very heart of Hindustan. On the banks of the Ganges, near Benares, there is a Sarnati stupa. On the edge of the mountainous India, there was an Amaravati stupa; fragments of its fence are kept in the London Indian Museum. In Baragat (Bargut, between Bilsa and Sarath) and in Mathur only stone fences with gates survived; further east, in Buddha-Gaya, the stone wall in front of the “temple” belongs to the oldest Buddhist times in India.

Fig. 558. Stupa in Sanchi. Kohl

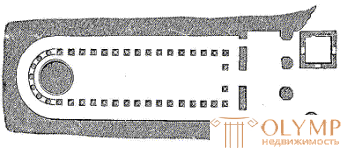

But the most numerous and remarkable monuments of ancient Indian art are cave structures that served as places of prayer meetings (chaytis), then monasteries with a large number of cells (vigars), but often consisting of a temple and adjacent cells. The cave temples we have already seen in the Egyptians (see Fig. 133); but the Buddhist striving itself to move away from the world was destined to expand, complicate, bring to monumentality and endow with abundant decorations those cave dwellings, which we have already mentioned, speaking of primitive peoples, and to which the latter resorted out of necessity. In some places, for the arrangement of such temples and monasteries, natural caves were used, but for the most part they were made with great difficulty artificially cut into solid rocks. The plan of these excavations was generally consistent with their purpose; in monasteries, a square or rectangular middle room with a ceiling supported by pillars is surrounded by small square cells. From the point of view of the history of art, no doubt, the temples themselves are more important, that is, the halls for prayer meetings, the interior of which resemble the premises of the ancient Christian basilicas, although they cannot be considered as the forerunners of the latter. In this case, the same needs led to the device of the same premises. These oblong halls, in which the side opposite to the entrance has the shape of a semicircle, are so extensive that their ceilings need props — in the pillars, which, like in Greek temples, separate the narrow aisles from the wide middle and sometimes , in the cave temples of Beds and Karli (Fig. 559), stand in a semicircle in front of the rear rounded side of the temple. Here, in front of them, there is a dome-shaped dagoba, an enlarged relic of relics; Such dagobas, or instead of them, subsequently appeared the colossal statues of the Buddha, so characteristic of many of these prayer halls. Light penetrates only from the side of the entrance, in which sometimes the door and the huge window make one hole; usually the semicircular, lancet, horseshoe-shaped or keel-like arch of the window is placed above the real portal, and before this the last is a sort of porch (veranda), bounded laterally by rocks. The hole itself is obscured by an openwork, luxuriously ornamented fence ( eng. Screen). The ceiling inside the cave halls is cut down in the form of a semi-circular or even a horseshoe-shaped vault, so that it gives the impression of a regular or convex vaulted vault. It is remarkable that such arches are usually covered with ribs, apparently borrowed from the style of wooden buildings and which sometimes, as a reminder of such buildings in the open air that existed before these cave temples and at the same time, are actually wooden.

Fig. 559. Plan cave temple in Carly. According to Ferguson

To the oldest cave structures of this genus, belonging to the III or II century BC. e., ranked temples in Bigar and Udayyadzhiri, in the Bengali east of the great Indian Peninsula. Much more numerous and important are cave temples and monasteries, excised in the solid red granite of the Ghat mountain range in the west of Western India.Cave structures in Bhaji, Kondane, Beds, Nasik, Pitalkgore, Ajante (Adyunt), dating back to the 2nd century, and in Karli - from the 1st century BC. e., as well as the later halls in Ajanta and the grotto in Kengeri on the island of Salsett, in the Bombay harbor, represent a long series of important in their value creations of ancient Indian art.

Единственная буддийская каменная постройка под открытым небом, которую относят ко времени царя Ашоки, – знаменитый девятиэтажный храм Будды-Гайи в древнем царстве Магада. По преданию, Ашока воздвиг это святилище напротив смоковницы, под которой Будда достиг высшей степени просветления. Каменная ограда, окружающая храм, действительно может быть отнесена к эпохе царя Ашоки. Сам храм в виде великолепной башни, причисленный, впрочем, Фергюссоном к разряду ступ, построен многими столетиями позже ограды, но тем не менее принадлежит к древнейшим первоначальным башенным храмам Индии. Что касается деревянных построек под открытым небом древнеиндийского стиля с вышеупомянутыми персидско-индийскими колоннами и чисто индийскими мотивами оград и арок, то с ними мы можем ознакомиться только по их изображениям в рельефах.

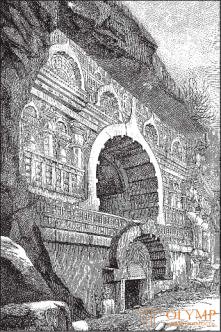

Fig. 560. Фасад пещерного храма в Насике. По Фергюссону

Ход исторического развития древнеиндийского буддийского искусства можно проследить при помощи пещерных храмов и каменных оград ступ.

Хронология древнейших пещерных храмов Индии, определяемая, впрочем, только приблизительно, дает нам понятие о постепенном переходе древних деревянных построек в каменные. Первоначальный деревянный храм, стоявший под открытым небом, представлялся как бы вдвинутым в пещеру.

In Bhaji, nests in the rock in which the logs of a wooden structure were placed are still clearly visible; the wooden ribs are still preserved in the temple of Carly (78 BC); the remains of the fence that separated the interior of the temple from the portico and which was initially wooden everywhere, can still be discerned in the tea house in Kondan. Where this wooden fence was not later replaced by a stone one, as, for example, in Badj, in the tenth (oldest) cave in Ajanta and in one of the grottoes in Pitalkgore, it is completely absent, and where it was stone, as, for example, in Beds, Nasik, Karli and other later caves, it is preserved.

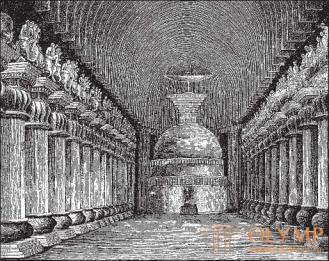

At first, the stonecutter simply imitated the forms of wooden construction, which is especially clearly seen in one of the Bigarsky caves and in the Kondan chayty, the facade of which differs from others with the greatest completeness and greatest unity, but then the builder gradually began to apply the motifs of wooden architecture at his own discretion, often as if joking , for example in Beds and Nasik (fig. 560), and even more arbitrarily in Carly; even the completely finished style of stone facades, as we see it in the V century. BC e. in the later grottoes in Ajanta, it still seems to be an imitation of carpentry work. All the friezes and wall fields of the facades are richly decorated with sculpture, and sometimes relief images of dagob, such as, for example, in Bhaji and Pitalkgor, serve as ornamental motifs. But the favorite ornament in Bhaji and Beds, as well as in Kondan and Karli, is the imitation of wattle, which was first real, and then made of wood and, finally, of stone. The ceiling supports inside the structure and their images on the facades, initially squat, simple, tetrahedral or octahedral, gradually turned into completely developed columns with bases and capitals consisting of several parts and with a short octahedral fust. Their base consists of a high pillow, serving its edge forward and lying on a quadrangular stepped plate; the capital first consisted of the above-mentioned West Asian bell, having the appearance of a flower cup turned upside down, and then began to consist of it, of the same stepped plate lying above it, as in the base, only turned upside down, and placed on this plate the aforementioned human figures or sculptures of animals that directly serve as beams. Fantastic figures like sphinxes appear on capitals already in Bhaji, and in Pitalkgora we see even real winged sphinxes. In Nasik, this ancient Indian column, which, despite the fact that some of its parts are West Asian, bears in general an Indian imprint, is in its full development; above it is decorated with the figures of the lying Indian bulls. The largest noble proportions are 30 columns of the cave temple in Carly, which is 38 meters long and more than 30 wide. On the abacus of each column there are two elephants kneeling, with Indian princes sitting on them. The general view of this temple, the most beautiful of all in India (fig. 561), is extremely unusual, and despite the inorganic nature of the transition of certain forms of its architecture to others, it gives the impression of calm and festive grandeur.

Fig. 561. The interior of the temple in Carly. According to Ferguson

The interior of the later cave temple in Ajanta, which dates back to the 5th century, makes a completely different impression. n e., namely due to the different ratios between its supports and the ceiling. Here, the columns even more clearly constitute an imitation of the former wooden supports, because above their capitals are cantilevers, as if supporting beams, and the fusts are partly covered with vegetable arabesques or elegant jewelry-like ornaments, partly richly decorated with embossed images and plastic round figures, including which now the main role is played by many times the repeating figures of the Buddha, whereas in former times only symbols were reminded of him — for example, a wheel, a shield, a hooked cross (the swastika ) Or traces of Buddha's feet (Fig. 562).

The figures of the Buddha give us a reason to go to the history of the development of Buddhist-Indian plastics. Regardless of some ancient clumsy statues on the rocks of the northwest, for example near Gwalior, we find even the oldest surviving sculptural works of India, according to the time of their origin, at that stage of development at which the characteristic signs of primitive art proper were experienced the body and the infidelity of their proportions, - on the stage where the art has already gone further than the frontality, how much the latter could not be kept in the images conceived in the mood of piety, and hen in the figures of the gods, playing the role of architectural pieces. In reliefs, all sorts of positions are transmitted, without the slightest embarrassment, starting with a strictly profile and ending with en face turning; The most free and difficult motives of movement are reproduced in round plastic. At the same time, Indian stone sculpture from the very beginning received a distinct national character. The softness of forms and flexibility of members of the Indian tribe, correctly noticed, are reflected in the sculptures. But the Indian sculpture is notable for the striking lack of even a hint of the anatomical features of the human body. Nowhere do we find a sharply grasped individuality of the person represented, nowhere does the play of muscles even receive reproduction, not a single motive of movement is traced anywhere to its anatomical causality. Nudity attracted the attention of Indian artists to a lesser extent than the luxury of gold jewelry and the tenderness of the fabrics covering the body. A whole series of artificial rather than natural laws of beauty soon brought blindness to Indian sculptors and forced them to create schemes instead of living beings.

Fig. 562. Footprints of the Buddha. Amavaratsky relief. According to Ferguson

The historical development of Indian sculpture can be traced best by those scenes that represent us sculptures on stone fences. Approximately by 200 BC. e. include fences in front of Baragat (Bargut) and Buddha-Gaia. More ancient are the reliefs of Baragat, depicting processions of elephants and lions to the sacred trees, in part, more than a hundred individual reliefs, Buddhist legends with explanatory inscriptions. The style of these reliefs, as Ferguson still insisted on and confirmed by Vincent Smith, seems, if not to take into account certain figures borrowed from the west, centaur figures, capitals of capitals and plant ornaments, in all respects more Indian, even more dry, strict and individual than the style of the subsequent time. Almost the same style we see on the fragments of reliefs of the Buddha-Gaia, depicting part of the worship of trees and Buddhist symbols, part of home scenes and floral ornaments. In the Berlin Museum of Ethnology there are some original fragments of this fence with images of winged antelopes and horses next to the natural figures of Indian animals - sheep, zebu, buffalo and horse.

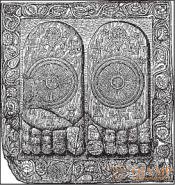

Ko II c. n e. Judging by the inscriptions made by Bühler, the famous sculptures on the four gates of the stone fence around the large stupa in Sanchi also belong. The southern gate, which, in any case, is older than the others, has been attributed to the first third of the 1st century AD. e., on the basis of the aforementioned studies should be attributed to 140 BC. e. Other gates were added a little later. Both vertical pillars of each gate, considerably exceeding the height of the fence itself, are interconnected at the top by three transverse cross-beams, which terminate in spiral discs; Between these crossbars there are three vertical columns smaller, so that above the gate we get something like a lattice. All the vertical and horizontal parts of this stone structure, which is an imitation of carpentry work, are covered from top to bottom with sculptural decorations. Images of plants and animals in the decorative part of these reliefs are usually not devoid of symbolic meaning, which can be argued at least with respect to winged animals on poles and transverse crossbars; but the vegetative ornament prevails in amazing stripes on the outside of the pillars and consists of natural and stylized, local and vegetative elements brought from the west. On one of the most beautifully ornamented fields of the eastern gate, the middle band is decorated with lotus flowers spread out in the form of wheels and buds of such flowers, while the narrow side stripes are filled with garlands of purely Indian flowers (fig. 563) - garlands for which, as Grunwedel noted, served as a garland of natural flowers, "hung in sacred places."

Fig. 563. Floral ornament on one of the pilasters of the stupa in Sanchi. According to Grunwedel

Among the reliefs of narrative content in Sanchi, we can again distinguish images of the worship of people and animals, sacred trees, sacred stupas, sacred pillars, scenes from the life of the Buddha and his later revivals (jataki). It is remarkable that at the same time the Buddha himself is never depicted, even in episodes from his life, and the relief reproduces only the incidental circumstances of the episodes, sometimes with a landscape background, executed ineptly, but sufficiently clear. But the Indian sculptors have repeated countless times the typical images of the ancient Veda god Indra with perunas in the form of a club and Sri (Lakshmi), the goddess of beauty. The goddess was depicted sitting on a lotus cup with her legs tucked under herself; to the right and left of her was placed over an elephant, which poured water on her head. Of the minor deities of Indian mythology, there are Nagi, snake men, whose king is endowed with five serpent heads, and Kinparis, a female spirit with a bird body; of the fabulous animals are depicted the Garuda birds, which, according to popular belief, are driven by gods, lions with heads of vultures and dogs, and the aforementioned bulls with a human face, pointed beard and lion's mane, forming straight strands - figures undoubtedly borrowed from the West. Thus, for example, the image of the worship of the entire animal kingdom of the sacred fig tree has quite a lot of foreigners next to the figures of Indian animals, drawn from nature. In the same way, vivid and natural, as far as was available for Indian art, human figures were reproduced, for example, in Sanchi. In their oblong heads, big eyes and thick lips, the Indian folk type is felt. In female figures, we find already unusually thin waists, spherical large breasts and very wide hips - features that are still considered in India as the main signs of female beauty.

We have already partially talked about the sculptural decorations of the most ancient Buddhist cave structures when describing the architectural forms of these structures (see Fig. 558). The reliefs of the famous cave in Udayagiri belong, probably, to the 150th. BC er these images of distant, partly still unexplained legends, executed boldly, pompously and according to artistic methods in the national Indian spirit, are capable of strongly influencing the imagination of the audience. By the first centuries BC, realistic groups of animals on the columns of the facade in Beds, a pair of human figures on the outside of the temple in Carly and the most ancient of the aforementioned magnificent figures on elephants that adorn the columns inside the temple can be attributed. All these 120 princes on 60 elephants above the capitals of the pillars of the underground temple in Carli, are purely Indian in their unconstrained decorative and beautiful postures and free soft forms.

The reliefs of the stone fence in Amaravati, sculpted only around 200 AD e. and now in the Indian Museum in London, are even more finished and ironed, but in many respects and more ordinary in execution than all the works mentioned above. But we cannot say with certainty whether, for the first time, here, along with the usual scenes of worship, images of legendary events and decoratively repeating figures of animals and boys, the Buddha himself and a halo, the shine of holiness around his head; however, the teacher is depicted still standing among his students and is still not transformed into an idol sitting with his legs tucked. Ferguson and Grunwedel believed that these reliefs were already influenced by the Gandhara school; but Vincent Smith, challenging this opinion, found in them, apparently with more thoroughness, although a slight, hardly noticeable, but direct Hellenistic influence, which can be traced along with Persian in all this ancient Indian art and, according to the aforementioned scientist, reflected here so strongly that there is doubt about the nationality of the main character of these works.

Only later, although, perhaps, immediately following the time of the execution of the Amaravati reliefs in Gandhara did the aforementioned Roman Buddhist art evolve, depicting Buddhist legends with figures in the costumes of the Greco-Roman decline (see Fig. 555). These sculptures are not so important for the history of Indian art, but for Buddhist iconography. Nevertheless, it was perfectly in the order of things that this Gandhara art initially adopted Indian images in their Indian treatment. And the figure of the standing Buddha, with which the evil spirit of Mara appears, the Gandhar artists borrowed more from the relief of Amaravati than she, on the contrary, transferred from them to him. Grunwedel noticed that the real idol of Buddha, sitting in contemplation with his legs tucked under him in the frontal position, is an invention not of the Gandhara school, and suggests that this ancient Indian type of Buddha was preserved in the clay sculpture from the Buddha-Gaya from the 6th century. (fig. 564, a). Therefore, the opinion that the dominant type of Buddha arose in the Gandhara school under the influence of the Greek ideal of Apollo is not justified in any way. Rather, the Gandhar school borrowed the Indian type of Buddha, whose place of origin is unknown, and, moreover, in its purely Indian form, with its purely Indian saggy earlobes, with its shred of hair between the eyebrows and the bulge of the skull at the back of the head, but not with all the other features belonging to among the 33 great and 18 small signs of the beauty of the "great being" given to him by written tradition and recognized as a religion, such as, for example, short straight hair on the head, which form the same curls, and sometimes look like yuchkovatyh crosses (swastika). That the Gandhar artists tried to bring the features of the Buddha closer to the features of the Greco-Roman Apollo is quite possible, but not as obvious as it is accepted to say. It is also enough that they brought closer to the Greco-Roman ideal of beauty the head of deified Indra, although they sometimes left him small oriental mustaches and, instead of dressing the hair on his head in the form of dry ring-shaped curls, gave them a shape in the late Greek taste, covering the crown with an Apollonian tuft of hair, and draperies were laid loosely ( b ). Grunwedel proved irrefutably that this Buddha of the Gandhara school, only slightly modified in the Greco-Roman spirit, served as a model for the entire Tibetan and in general for the entire northern Buddhist school. But we are no less convinced that this Buddha, with all its details, is an alien phenomenon that has penetrated from the outside, not in Indian art, but in Gandhar art.

Starting from IV c. Buddha statues are no longer a rarity in all Indian sculpture. Among the most interesting images in Ajanta are the “Childhood of the Buddha” in the 2nd and the “Temptation of the Buddha” in the 26th cave (according to the English account). Plastic V in. here it seems confident, but in form it is somewhat puffed up, but in content is mystical-Buddhist; This later time of Buddhist art also includes two commonly mentioned Buddha statues, 7 meters high, located at the ends of the portico of the cave temple in Kengeri.

In Ajanta, we have the opportunity to familiarize ourselves with the Indian wall painting, from which, in addition to little-studied remains in other caves, important, but unfortunately, more and more crumbling traces are preserved only in 13 underground halls. The most significant or at least the largest fragments of these paintings on the walls and ceilings, painted in part a fresco, part a tempera on a thin layer of plaster, are in rooms 1, 2, 9, 10, 16 and 17. The oldest of them, in the 9th and 10th halls (c), are attributed to the end of the 2nd c. n e., that is, the same time as the reliefs in Amaravati; the later ones, to which the paintings belong in the 1st and 2nd halls, may come down to the 7th century, but most of them are written in the 5th or 6th century. Their copies, which were in the South Kensington Indian Museum, are partly destroyed by fire, but the drawings exhibited instead give a great idea about this painting. John Griffiths published them in two luxurious volumes. These paintings depict scenes of the Buddha’s existence before his incarnation and his last years.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)