When mankind became acquainted with metals and began to use them, a new epoch came again - an era more rich, more brilliant, more mobile. However, metals did not obey man all at once. The best experts of all countries claim that in most regions of the globe, the time when only copper, bronze and gold were processed preceded the era when iron and other metals came into use. The transition everywhere was done gradually. But both the beginning and the end of the Bronze Age, which coincides with the beginning of the Iron Age, in different, sometimes even in neighboring places, should be attributed to very different times. We are not talking about getting to know metals at all, but about using one or the other of them. In Egypt, the use of iron changed the use of bronze at a time when in Europe bronze had just begun to replace stone. Throughout the rest of the “black” part of the world, abounding in iron, this metal began to be used before bronze, and in other areas almost all of iron was processed from all metals. On the contrary, American cultural nations still used only copper, bronze, gold, and partly silver, when the Europeans, 400 years ago, met the inhabitants of the New World. In most cultural countries of Asia, one can point to the existence of a Bronze Age; in Europe, all excavations and finds confirm the opinion of ancient Greek and Roman poets, of whom Lucretius directly stated that "the use of bronze was known earlier than the use of iron."

Bronze, or "ore" (Erz), as poets and classical archaeologists sometimes call it, is a mixture of about 5 to 15 parts of tin with 95 or 85 parts of copper. The most common ratio is the ratio of 10 to 90. It goes without saying that acquaintance with copper should precede its alloy with tin. Therefore, it was possible to consider in advance possible that people tried to process copper in its pure form, until they were convinced that the addition of tin to it makes it harder and gives it a lighter color. Indeed, in the last decade, the copper period preceding the Bronze Age has been established for vast spaces of the globe; this was proved with respect to Hungary, Pulzky (Pulszky), with respect to Switzerland - Gross, with respect to most European countries - Flies and Gampel. But since pure copper tools and weapons, usually devoid of any adornments, hardly differ in their forms from tools of the Stone Age, then, as we have already noticed, they view the short copper period not as a separate cultural stage, but as the last part of the Stone Age. . Therefore, Görnes speaks of the "impotence of copper", which could not alone overcome the stone and had to be united with the "miraculous tin" to defeat it.

Prehistoric bronze areas, especially interesting for us, lie in Central and Northern Europe. The bronze art of Egypt, the great ancient Asian monarchies and Eastern Greece cannot be separated from the historical art of these countries. With the copper and bronze era of America, we will meet when considering the art of the ancient cultural states of this part of the world. Only in Europe can one specify a bronze epoch that corresponds to a particular prehistoric stage of art, but this is not true to the same extent for all its parts. The bronze culture of the southern peninsulas and the regions of Central Europe, most accessible to its influence, especially France and parts of Austria, is so quickly absorbed by the iron culture advancing from the south, which already at the very beginning is more primitive-historical than prehistoric in nature that the bronze culture can hardly be taken into account in these localities. We can consider only the Central European and Northern European Bronze Age, which became available to us thanks to separate studies conducted in Upper Bavaria Noack, in Bohemia - Rihli, in Western Prussia - Lissauer, in Great Britain and Ireland - Evans, in Hungary - Undset and Gampel, Scandinavia - Sophus Muller and Montelius.

For the European metal culture, we cannot recognize the same originality as the European art of the Stone Age. Everything indicates that the ability to extract and process metals originates from West Asia. From here, a bronze stream glittering in gold could pour out, on the one hand, into East and North Asia, and on the other, into the Mediterranean region; but he had to take a third direction. It penetrated Northern and Central Europe, probably not through Northern Asia or through Greece, but through the shores of the Black Sea and the Danube. From the Danube countries he even moved to the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula and to Northern Italy. He reached the north of Europe, which, for his part, along the same paths as he received bronze utensils, sent to the south in exchange for it his amber, he reached without hindrance along the big German rivers. The consequence of this was that the pure bronze culture developed most fully and richer in Hungary, Switzerland and the North, where, on the one hand, Great Britain and Ireland, and on the other, Scandinavia and Northern Germany constituted the provinces of the great bronze kingdom, in which as numerous open cast products prove, bronze was first cast and only then began to be machined with a hammer and subjected to forging.

The importation of a brilliant and flexible metal produced a huge revolution in the common stock of the then European life. Most of the tools and weapons made from stone, horn and bone were made of bronze in the previous epoch. The daggers turned first into short obliques, and then into long swords. Axes and cutters took on special forms, which researchers of the Bronze Age called the collective word “Celte”. The pins received a varied decorative look and, equipped with special adaptations so that they could not be unbuttoned, were already turned into buckles (fibula), which belong to the artistic objects that characterize the next epoch - the prehistoric iron age. Many items and jewels began to be made from bronze or gold, for which in the Stone Age they used low-processed or completely unprocessed natural materials. Due to the flexibility of the metal, decorative shapes that were unknown until then appeared. Rounding came into its own. Began to cast or forge headbands, tiaras, neck rings, hand and foot bracelets, finger rings, chains and chains; clothes or household items were decorated with round bronze shields.

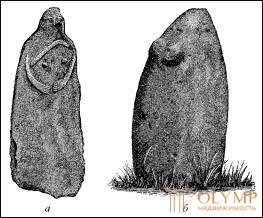

However, the basics of other arts - we are silent about the ornamentation so far - and it didn’t change immediately. Houses and huts in Northern and Central Europe continued to be built on the same principles as in the Stone Age. Swiss piling structures are still the most revealing remnants of human dwellings from the Bronze Age. They are now farther from the shore than before, and the walkways connecting these structures to the shore sometimes reach a thousand feet in length. Villages become more extensive and sometimes turn into flowering, populous places, located above the green or blue surface of the water. Pile platforms and huts are built better: piles are always hewn, weaving of rods is sometimes replaced by vertically impacted logs. The megalithic method of piling up on one another uncouth gigantic stones at the construction of tombs (see Fig. 10) gradually disappears, although for some time it drags its existence in the form of so-called cyclopean walls; in some places it survived even the Bronze Age, and in some cases, even in the north, it reached to a certain ideal greatness. The cyclopean wall is made up of huge quadrangular or polygonal boulders, the edges of which fit as closely as possible to each other and are not fixed by cement. Stone pillars continue to exist in the north right up to historical time, but many of the menhirs of France and Britain live to the Bronze Age. It is remarkable that some of them, who from the very beginning personified gods, are now supplied with hints on parts of the human body. The most interesting in this regard are the Kollorg stones (in the Gardens Depot), located in the Rhodes Museum (Fig. 16, a), - idols with childish embossed hands stuck to the body, depicting the female deities of the Champagne Stone Age (see Fig. 13 ); remarkable are the menhirs of Sardinia arranged in circles, which, judging by the women's breasts marked on them, should be considered as experiments on the personification of deities in a human form (Fig. 16, b).

Fig. 16. Stone pillars: a - kollorgsky stone; b - Sardinian menhir. By Kartalyaku

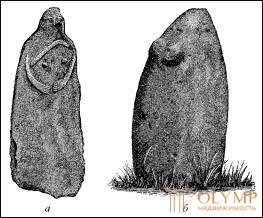

But the most remarkable example of the megalithic structures of the north is the famous Stonehenge, preserved in majestic ruins on a vast open desert desert in Salisbury, South England (Fig. 17). The sandstone pillars that make up the outer circumference of this monument, commonly mistaken for the temple of the sun, are provided at the top with protrusions that correspond to holes in the stone transverse beams resting on them. The pillars and triliths (three stones, one of which lies on two vertically standing) inner oval circles consist of Irish granite, which could only be brought here by sea. All posts are hewn from four sides. In the Stone Age, the inhabitants of England must not be allowed to achieve technical success, without which the production of this building is unthinkable, although it is usually referred to the Stone Age: towering over the graves of the Bronze Age, Stonehenge belongs to this Age itself.

Fig. 17. Stonehenge near Salisbury, in southern England. By ranke

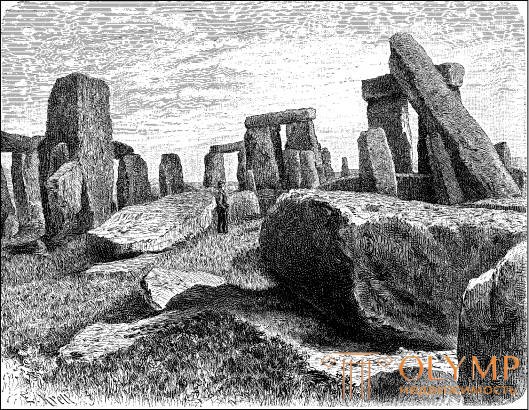

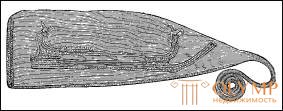

Attempts of monumental drawing art, found on dolmens, menhirs or on natural rocks in the Stone Age (stones in the form of bowls or stones for painting with dimples and other signs), in Scandinavia in the Bronze Age develop to the first steps of historical wall painting or historical relief with rich figures images. For this part, Scandinavian drawings on the rocks, commonly referred to by their Swedish name Hflllristningar, deserve attention. They are found here and there on the plates of grave chambers, but most often on open, somewhat inclined, by no means vertical, and sometimes on almost horizontal surfaces of smooth granite blocks, into which they, as opposed to contour drawings on later runic stones, are embedded with their whole plane . Most of these images, sometimes occupying a few meters in width and in height, are in the Swedish provinces of Boguslen, Östergotland and Shonen, as well as in the southeastern part of Norway adjacent to them. Balzer and Rydberg published them in a large, compiled by them essay. Often found bowl-shaped indentations and incomprehensible symbolic patterns of concentric circles, circles with crosses, spirals, wheels, etc., which can be viewed as the rudiments of shaped letters, as well as ordinary images of various weapons and various utensils, such as swords, axes, shields, reproducing Obviously, the world of forms inherent in the Bronze Age - all these drawings are not as important as the images of people, horses, bulls, ships, wagons and plows, which clearly represent the life of the heroes long past their times. The main role among these images is played by ships - partly large multi-vessel ships with numerous rowers, vessels that look large enough and strong enough to carry even more significant gravity over the sea than the Irish granite pillars mentioned above, which we see at Stonehenge. Here we also find images of rowers sitting on the benches of the ship, riders with shields and spears in their hands, farmers, following the plows. Also depicted are naval battles, mooring to the shore, horsemen’s fights and pasture scenes. There is no shortage of scenes of religious ceremonies, which, however, we cannot explain. Fig. 18, a, presents a scene in a pasture, fig. 18, b, - the battle of horsemen, depicted on one rock in Tegnebi (in Bohusleon).

Fig. 18. Drawings of the Bronze Age on the rocks of Tegnebi, in Bogusleen. By montelius

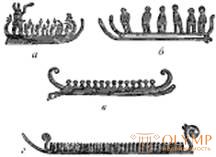

All these images are nothing more than baby talk in the language of forms. The correct attitude of individual figures and objects to each other, the spatial integrity of the picture, the skillful processing of individual forms is out of the question, but a kind of vividness and clarity of the image method give some of these paintings a kind of artistic charm; moreover, the difference of views on nature is constantly displayed in various images. In this sense, it is interesting to compare with one another the four vessels depicted on the rocks of Boguslena and reproduced in Fig. 19. In the first (a) and in the second (b) we see an attempt to impart a human image to seafarers traveling on a ship; on the third vessel (c) people are represented without members, only with heads, like pins; in the fourth (d) instead of people we find a series of identical nightstands. The question is: did the development take place in this or in the opposite direction? Shaped menhirs, as we have seen, gradually acquired separate parts of the human body, and Görnes repeatedly pointed out that in prehistoric earrings, human forms evolved from geometric figures. Nevertheless, in the case under consideration, in which the original purpose was to imitate nature, it seems more likely that in the last image of the vessel the human images of his crew were turned into geometric figures.

Fig. 19. Drawings of the Bronze Age on the rocks in Bohuslion, depicting vessels with their crew. By montelius

Fig. 20. Development of the Bronze Age

Bronze objects characterizing the entire epoch in question were cited partly in graves and urns for ashes, partly in remnants of dwellings, especially remnants of pile structures, partly in whole piles (treasures) in those places in which they were once buried on purpose -or cause or chance (Werkstattfunde, finds at the place of manufacture). All these bronze objects, taken from the earth after three millennia, now fill the prehistoric collections of different countries and, despite the fact that they are covered with blackish-green or bluish rust, they also speak in clear language for us about the taste and art of the past times. Montelius divides the millennium of the bronze domination in the north into six successive periods, beginning around 1650 BC. e. Sophus Muller recognizes only four periods, approximately 200 years each, beginning around 1150 BC. e. Here we must adhere to the main features of the general course of development.

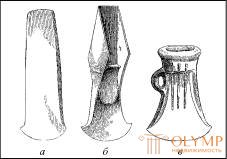

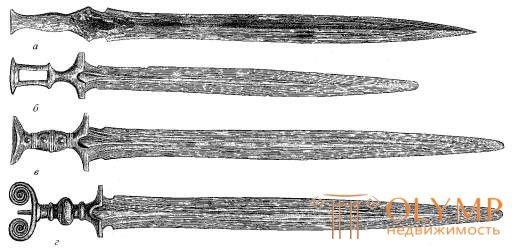

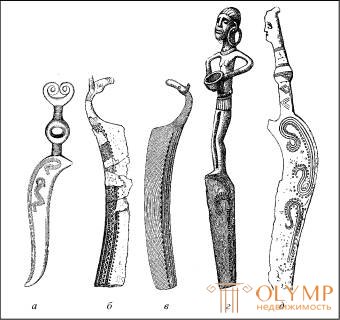

True, the question of how celites (fig. 20) evolved from flat celts (a) into celts with appendages (Paalsaben, b) and into hollow celts in, hardly relates to the history of art, since it is all just the most expedient attaching the arms to these products. But our drawing still gives a visual representation of such modifications. A more artistic character is the development of the arms of swords . Flat, tongue-shaped handles of the most ancient swords (Fig. 21, a) and slotted handles of swords of somewhat later origin (Fig. 21, b) were also supplied with a wooden or bone knob; by decorating the entire handles of the flowering pores of the bronze period (Fig. 21, c), one can follow the technique of the former attachment of such knobs. In the Antenna swords with horn-shaped handles (Fig. 21, d), the spirals both in the north and in the south of the bronze kingdom are a completely original motive of the epoch under consideration and, moreover, in the most characteristic form. The depicted swords come from Swiss pile structures: the first from Tille, the second from Auvergne, the third from Möhringen, the fourth from Corselett; the second is kept in the Neuchâtel Museum, the others are in the Gross collection, in Neuville. Antenna swords found in the north are even recognized by Scandinavian scientists for goods brought from the south.

Fig. 21. Swords of the Bronze Age. According to Gross

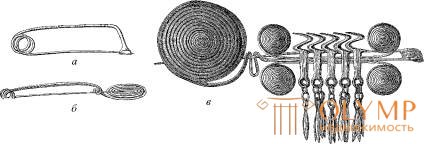

In artistic terms, the development of buckles, or brooches, endowed with its elasticity, so to speak, inner life, is even more interesting. In the Bronze Age, these buckles are not found at all in most European countries, only rarely in simple form in Mycenae, Swiss pile structures and Upper Italy; but they have already achieved some artistry in Hungary, Northern Germany and Scandinavia. Simple fibulae stored in the Budapest Museum, presented in Fig. 22, a and b; the luxurious Hungarian fibula of the same museum is also depicted here (Fig. 22, c).

Fig. 22. Hungarian fibulae. According to Undset and Gampel

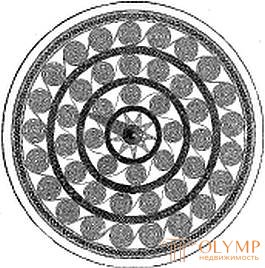

Обращая свое внимание прежде всего на художественные особенности искусства бронзовой эпохи, мы должны признать весьма важное значение за видоизменениями чисто декоративных форм – орнаментов. Орнамент в искусстве бронзовой эпохи продолжает быть в сущности геометрическим: с одной стороны, геометрические украшения бронзовых предметов представляются разработанными прямолинейными узорами каменной керамики (см. рис. 14), с другой, вследствие способности металлов гнуться, декоративные геометрические узоры составляются из кривых линий, которые лишь в отдельных случаях появлялись в конце позднейшей каменной эпохи. Орнаментация художественных изделий бронзовой эпохи изобилует кругами, полукругами, спиралями, простыми или пересекающимися по мере своего распространения волнообразными линиями ("бегущий пес" или "полоса водяных волн"). Карл фон ден Штейн говорил: "Проволочная техника монополизировала давно известную дометаллической эпохе спираль, как будто бы она была изобретением металлической эпохи". Однако наиболее выдающиеся из скандинавских исследователей доисторических времен, каковы Оскар Монтелиус и Софус Мюллер, согласны между собой и с учеными других стран в том, что спираль древнейшей скандинавской бронзовой эпохи произошла непосредственно от микенской спирали. При этом, конечно, кажется странным, отчего одновременно со спиралью не были заимствованы и прочие мотивы микенского искусства. Впрочем, относительно этого вопроса еще возможно сомнение; во всяком случае, своеобразные вариации и применения спирали в скандинавском искусстве позднейшей бронзовой эпохи – свободные изобретения этого искусства.

Fig. 23. South Swedish bronze shield with decorations. By montelius

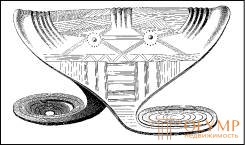

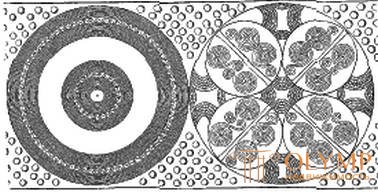

In fig. 23 depicts a South-Swedish decorated bronze shield stored in the Stockholm Museum; in fig. 24 - Bohemian shield with spiral circles and linear ornaments, located in the museum of Caslav society; in fig. 25 - decorations on the Upper Bavarian chest plate from a thick bronze sheet found on the Ringa Lake (Munich Prehistoric Museum).

Fig. 24. Bohemian hand shield. By rihley

The transition of the bronze era ornamentation from the strict forms of a circle, a semicircle and a spiral to more diverse wriggling wavy lines, to the line in the shape of the letter S and to an arbitrarily bent spiral can be traced particularly well in Scandinavian bronze art. For example, the Swedish decorated shield (see fig. 23) was made in the strict style of the Bronze Age. Decorations of a hanging vessel from Westgotland, Stockholm Museum (Fig. 26) have a freer character; especially, the shapes of the wavy twisted lines of the lines on the blades of many Scandinavian and North German bronze knives are fantastic. It is rather curious that in these ornaments, especially on the blades of knives, the same images of ships as we saw on the rocks are often repeated (see Fig. 19); these images take on more or less schematic forms, but very understandable for the initiate. For example, on the Danish knife the ship is clearly visible (Fig. 27), the Copenhagen Museum. This is also adjacent to the first experiments of Scandinavian animal ornamentation. Curvilinear decorations are sometimes supplied on one side with images of more or less easily distinguishable animal heads and turn into dragons, snakes, sea horses and other animals, as it can be seen, for example, on the lid of the hanging vessel (see Fig. 26) and even better. - on the antenna from Holland, which was previously stored in the Hamilton collection (Fig. 28, a). More specific images of animals in the form of a flat ornament, especially a number of birds on the famous shields of the Stockholm and Copenhagen museums, and close to them ornaments in the form of birds on Danish, North German and Hungarian vessels, are recognized by the Scandinavian researchers themselves of southern origin, as objects on which they are found, no longer cast, but minted, and are put in connection with the simultaneous oldest iron culture, namely the Hallstatt, with which we will meet later. On the handles of knives, plastic heads of animals are found even in the oldest Scandinavian bronze period, and horse heads are especially frequent, as, for example, on a bronze knife from Åland (fig. 28, c), the Stockholm museum, and on a knife from Holstein (fig. 28 , b), Kiel Museum.

Fig. 25. Ornaments on the Upper Bavar's breast plate made of sheet bronze. By noack

Fig. 26. Visigothland hanging vessel. By montelius

Fig. 27. Danish knife, decorated with the image of the ship. By montelius

On the handles of Scandinavian knives, we also find the best images of human figures from all that are only found in the Bronze Age. It should first of all mention the famous handle of the knife, found near Itzegoe, in Holstein, and stored in the Copenhagen collection (Fig. 28, d). She represents a half-naked, but richly decorated woman, standing straight, completely en face and holding a vessel with both hands in front of her. In her ears - huge earrings in the form of rings. The face is flat, the body is thin, but its proportions are fairly true. Almost the same head, but only one head, adorns the handle of a bronze knife from Skanderborg, from the same collection; in the same way a knife from Ditmarshen (fig. 28, e), private property. That these arms, to which several more bronzes having a human form can be counted, are the essence of the product of the north, prove, as Forrer also remarked, that adorn their blades, purely northern images of ships or dragons, characteristic of the Bronze Age. Undseth also sees only "some connection between these patterns and human figures found in the more southern and earlier group of iron culture"; and we, for our part, do not deny that they have reflected to some extent southern influence. But from modern with them there is little in Europe such that would show such an understanding of forms and attentiveness of performance, which we notice in them.

The art of pottery production in the Bronze Age in Northern and Central Europe hardly made a step forward. The thin, rectilinear, apparently, punctured patterns of the newest Stone Age disappear little by little, giving way to coarser, more plastic, although, perhaps, sometimes more effective decorative motifs.

Fig. 28. Knives of the Bronze Age. According to Montelius and Mordorf

On the one hand, bulges and warts are more common, and on the other hand, more deeply embedded grooves and recesses.

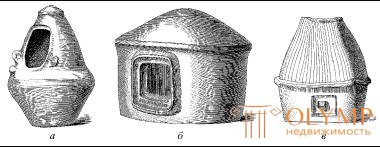

Here we can point out only two distinctive types of pottery: the urns in the form of dwellings and the front urns. True, both kinds of vessels survive the Bronze Age, and the development of the actual urn-shaped urns, at least in the north, takes place in the Iron Age; however, the predecessors of these vessels, as we have seen, belong to the Scandinavian stone age. The fact that the appearance of urns in the form of dwellings belongs to the Bronze Age is proved by Lish and confirmed by Lissauer.

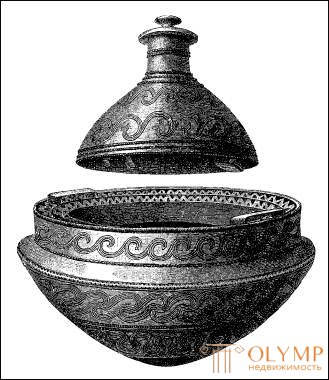

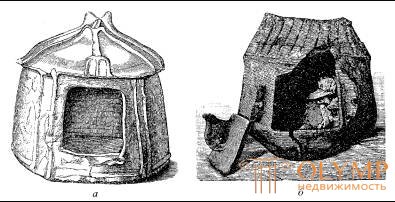

The idea underlying the urns for ash-shaped dwellings could no doubt be developed only in the later Bronze Age, when it became customary to burn the bodies of the dead. The remains of a loved one, it was desirable to arrange an attractive shelter, which is a copy of his earthly home; for the history of art, these urns in the form of dwellings are important, precisely as the similarities of houses and huts of a very remote era, especially since such urns were by no means the possession of all prehistoric peoples in general, but were used only in certain areas, mainly in Northern Germany and Middle Italy Therefore, it is impossible to consider the convincing opinion of some that the bins in the form of houses were borrowed from Central Asia. The history of the development of a dwelling house, which we have already met with the help of Montelius in the previous chapter, can be traced through the German urns, which have the form of dwellings. The simplest bins are a kind of hut with a high cone-shaped roof and with a high entrance door, to which, both outside and inside, can only be reached by a staircase, with the door being locked by a log in the form of a bolt; for example, the urn of Polleben, the provincial museum in Halle (fig. 29, a), and the urn of Unseburg and Seddin, the Berlin Museum of Ethnology; a round hut with a domed roof, something like a tent, with an entrance door placed already below; the urn of Kikindemark, the Schwerin Museum (Fig. 29, b ) is an imitation of such a house; a quadrangular hut with a high, sloping but not yet combed thatched roof towering over the ledge of the cornice, as we see in the famous Aschersleben urn, the Berlin Museum (fig. 29, c ), and an oblong peasant house with a sloping roof, roof rafters, comb and cornice, reproduced in Professor Buttner's Dessau urn (Fig. 30, a). Italian urns in the form of houses, found first in the Albanian mountains, then in Etruria, especially in Corneto and Vetulonia, belong to a higher level of culture, since they reproduce buildings with a pediment; compare with the previous Albanian urn stored in the Berlin Museum (Fig. 30, b ).

Fig. 29. Urns in the form of houses of the first bronze era. According to Lissauer and Lishu

Fig. 30. Urns in the form of houses of the second bronze era. By Becker and Lish

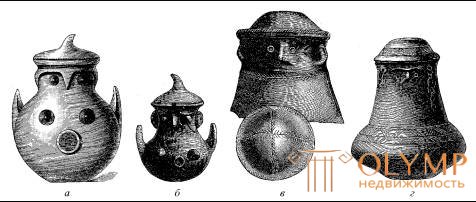

Fig. 31. The face-shaped urn of the bronze age. According to Schliemann (a, b) and Berendt (c, d)

The face-shaped urns were made with the aim of giving the clay vessels a human appearance: attempts were made to paint the entire vessel in imitation of the members of the human body; the face was depicted on the top of the vessel, especially on the neck; sometimes the most convex part of the vessel would look like a whole head. Since such bins are often found together with vessels for storing the ashes of the dead, which can be said, for example, of North German front-shaped bins, when they were made, they tried to some extent to give them something human, that is, to create a departed monument resembling a human form. But facial urns do not always have to be considered burial urns; thus, the urns dug out by Schliemann from the lower prehistoric layers of Troy are not burial in any way, and their origin does not need any other explanation than that derived from the fact that ordinary configurations of earthen vessels themselves led to an idea of the forms of the human body. After all, even without thinking about the facial urns, we are talking about the neck, leg, handles of blood vessels. Therefore, there is no need to assume that during the development of the production of facial urns, there was some connection between different localities and different times; the areas where they occur in prehistoric times are Western Asia, mainly Troy, Italy (especially Middle), and Northeastern Germany (mainly the Pommerellen region, lying to the west of the Vistula). Schliemann wrote about the trojan facial urns, Undset about the Italian urns, Berendt about the Pommerellens. As a characteristic sample of the Trojan face-shaped urns of the Bronze Age, you can point to the vessel found by Schliemann, stored in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (Fig. 31, a). The cover of it is a headdress. The face is located on the neck and is also devoid of mouth and poor features, like images of female faces dating back to the Stone Age and found in the Champagne caves. At the later Trojan urn (Fig. 31, b ), the ears, nose and eyebrows are designated more definitely; she is also in Berlin.

Fig. 32. Darslubskaya urn. According to the Convention

In spite of some local deviations, most of the Pommerellenian urn-type urns belong to the same level, such as the "imperial urn" (Kaiserurne) in the regional provincial museum in Berlin (Fig. 31, d ). Original bronze or iron rings or imitations of them, hung in the ears, nose, and sometimes around the neck of the Pommerellenic urns; they are also peculiarly subtle, barely noticeably scrawled images of animals, people, carts, and horsemen found on many of these urns. Characteristic drawings of this kind we see, for example, at the darslubskaya urn (Fig. 32), a museum in Thorn, Poland, which, however, cannot be called facial. On the Pommerellenian facial urns, especially numerous in the Danzig Provincial Museum, as well as on Poznan, Schleswig, and Semigrad vessels close to them, usually all parts of the face are marked. On better-trimmed vessels, such as, for example, the Gneshen urn (Fig. 31, c ), stored in the Poznan Museum, even the mouth is clearly marked.

We consider it inappropriate to speak here about the Egyptian, Syrian-Phoenician, Etruscan, Roman-Rhine and American facial urns; with some of them, perhaps, we will meet later. But let us note now that some phenomena that attract our attention at the initial stages of culture, at its highest levels, recede into the background before the phenomena more important.

Imagine, in conclusion of this department, the general picture of the art of stone and bronze eras, we will have to recognize that the peoples, and above all the European nations, really reached the initial stages in all the arts, the sacred fire of which must have been for an infinitely long prehistoric period. warm them up afterwards; but we have to say that the original history of art is mainly the history of primitive ornamentation.

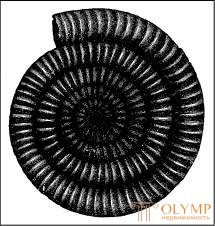

Fig. 33. Ammonite. According to Neymayru

If we again ask ourselves the question of the origin of all the ornaments that we have already met, then we will have to answer that it would be wrong to remove all the ornaments from one source; we saw that they were partly due to imitation of nature, partly due to the improvement of technology, partly due to symbolic representations. Having decorated himself, a person feels the need to decorate his own weapons and utensils too. He does not think where the jewelry originates from. He looks and imitates what he likes and seems appropriate.

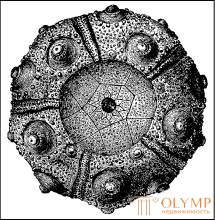

Fig. 34. Ekhinit. According to Neymayru

The first source of all kinds of jewelry, we believe imitation of nature. There is nothing to prove that all the ornaments drawn from the animal world, especially the grandiose ornamentation of the diluvial era, are based on imitation of nature. The very question of the origin of the ornamentation concerns mainly geometric ornaments, which are often and, in our opinion, incorrectly made solely from well-known technical motifs. It cannot be said that nature did not give any regular geometric patterns to follow. We have already pointed to crystalline formations in the inorganic nature, among other things to amazing snowflakes in their correctness. It is necessary to mention once more the petrified lower breeds of animals, and all the more insistently that, judging by numerous finds, people in the considered remote times fully understood the decorative value of these ammonites (fig. 33), echinites (fig. 34) and even belemnites (fig . 35). Ammonites drilled for stringing are often found not only among the inhabitants of the diluvial caves, but also in Swiss pile structures; Klopfleish argued that he found ekhinits in the graves of the Stone Age as valuable offerings to the dead. One glance at these products of nature is enough to make sure that they could serve as patterns for ornamentation. On the ekhinites we see beautiful patterns consisting of circles with round buttons in the middle and of variously arranged lines; ammonites so common are prototypes of all spirals; belemnites serve as samples of pointed round sticks.

Fig. 36. The pattern on the back of a viper. From nature

Fig. 35. Belemnite. According to Neymayru

But the world of non-extinct animals, which were so closely observed by ancient primitive peoples, is replete with all sorts of geometric patterns of this kind. Without going beyond the northern European and Central European world of animals, we point out the pattern adorning the viper's back (Fig. 36) and the pattern of a zigzag strip depicted on an ornamented bar from Mongodieu (see Fig. 7, e). Look at the circles, semicircles, parallel lines on the wings of the northern butterfly-swallowtail (Fig. 37) or on concentric circles and zigzag lines on the wings of the butterfly-shrews (Fig. 38); Look also at the movements of the snake in the grass and compare them with the twists of the stream flowing among the fields - and you will needlessly ask where did people draw such forms as zigzag and wavy lines, like circles and spirals, with which we had to meet in the diluvial art. This indication, made even before the appearance of a great work by Haeckel “The beauty of forms in nature”, we do not intend to distribute by listing the richer and more complex, but more distant forms, since only the one close to us and accessible to us can be evidence-based in the present case.

The plant world is also in abundance of symmetrical and correctly geometrical arrangements of lines. An example of such an arrangement is the calyx of any flower, each complex leaf, each horsetail. Recall already mentioning

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)