A new era has arrived. Europe at that time was no different in shape from the modern, and it was dominated by the current climate. Mammoths became extinct, reindeer moved closer to the Arctic Circle; A dog became a faithful companion of man, and he, apart from hunting and fishing, was engaged in cattle breeding, and soon afterwards in agriculture; I also learned to spin and weave, sculpt hands with clay vessels and burn them on fire, and if in some places I still lived in caves or artificially dug pits, I still mostly preferred to build huts of stakes, clay and brushwood for myself cover them with branches, reeds or straw. People in that era began to give birth to a belief in a higher power, expressed primarily in the care of the dead and in the delimitation of sacred land.

When exactly the Neolithic epoch began, the existence of which can be traced along the formation of the Earth, it is impossible to determine with precision, as the beginning of the Paleolithic epoch cannot be precisely established. But the end of the later Stone Age, which always coincides with the beginning of the era of metal processing (although the appearance of a few metal, especially copper, objects still does not give the right to conclude that the transition from one era to another has already been completed), in various areas of the inhabited earth came very different times. In Egypt and Babylonia, metals were used as early as the 4th millennium BC. e. The stone age of the North American Indians, who processed their copper only in a "cold" way, like stone, and of the Pacific islanders, who still know only imported metal products, continues until they come into contact with Europeans. As for Europe, it is possible, by an average, to take 2000 BC. e. for the approximate end of the Stone Age, although the southeast of this part of the world became acquainted with the processing of metals two or three centuries earlier, and the Scandinavian north only a few centuries later.

Representatives of the Neolithic period of development of Europe are considered to be the nationalities of the Aryan tribe, with the passage of time, winning over its dominance throughout the globe. If Europe itself is believed to be the birthplace of the Aryan tribe, then the art of the newest European Stone Age should be considered the first manifestation of the artistic aspirations of this tribe. True, in this case we are on very fragile soil. While, on the one hand, prominent scientists, headed by Solomon Reinach, advocate for the independent and independent emergence of all the prehistoric art of Northern and Central Europe, other equally prominent people of science, led by Max Görnes, about the primitive history of art, they hold the view that all the artistic creations of Europe originate indirectly from Mesopotamia and Egypt, directly from the islands and coasts of the eastern Mediterranean, ac that works in Neolithic Central Europe can see only a reflection of art south and east.

To recognize unconditionally, as well as to unconditionally deny any influence whatsoever here, is equally easy. We will always consider a significant proportion of unpretentious Neolithic forms as the common patrimonial wealth of peoples, but at the same time we must recognize the dependence of rare and complex, and therefore, later works on neighboring, more ancient and related forms. The degree of culture and art on which the newest stone age stood, which Görnes rightly separated from the first metal era from its point of view, precisely in Northern and Central Europe, still retains its own special cultural and historical imprint.

The earliest period of the later stone age hardly differs from the last diluvial era in the form of stone tools. In France, Campigny (Dep. Of the Lower Seine) are classic sites of finds dating back to the oldest period of the later Stone Age, while in the north, heaps of waste (Kjukkenmuddinger) on the Danish coast of the Baltic Sea already exist, perhaps 7,000 years ago. Similar heaps of shells and debris are found in many coastal locations in Europe, America and Asia.

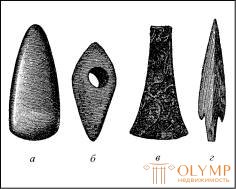

The most important places where the tools, utensils and vessels of the middle period of the later Stone Age are found are the remains of the former dwellings and the tombs belonging to them. In the dwellings and tombs find weapons, as well as smooth and polished tools, which are considered particularly characteristic of that time. Flintware was still sometimes unpolished, but most of the stones that were processed along with flint, it was really necessary to smooth and polish smoothly. The weapons used in solemn occasions were made of green or greenish stone; the most valuable axes and axes were made of jade, iadeite, or chloramelanite; A coil was also used for this kind of items. Until it was thought that jade was found only in Asia, it was easy for defenders of the origin of all these objects from that part of the world to defend their opinion. But after it became known that in Europe, jade is found in its raw form, especially since Adolf Bernhard Meyer proved that this stone, distinguished by hardness and beautiful color, comes across even in the Alpine region, these questions became easier to solve. In fig. 8 depicts several Neolithic tools: a - a jade cutter from Castrojovanni, in Sicily, stored in the university collection in Palermo, b - a pierced stone hammer from the Lüneburg steppe, located in the provincial museum in Hanover, in - an unpolished flint cutter from Schonen, the apus spearhead from Norrland; the last two items are from the Stockholm Museum.

Fig. 8. Tools of the last stone age. According to Adrian, J.G. Miller and Montelius

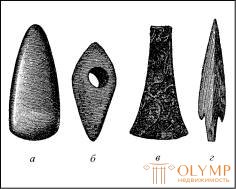

Stone, wood and horn (often the horn of an ordinary, rather than reindeer) still served as the main processing materials in the later stone age, but at the same time amber, the "gold of the north", began to play the role of a new decorative material. Amber earrings are found in the form of various figures, even, as we shall see, they sometimes have the shape of a man. In fig. 9: a large Swedish amber pendant, Stockholm Museum, b - East Prussian amber ring, Königsberg Museum of the Physico-Economic Society. But the poorer population, who lived far from the seashore, made their jewelry from bones, stone and clay, as evidenced by Johann Ranke's finds in neolithic dwellings in the cliffs of Franconian Switzerland: c and similar decorations, the Munich Prehistoric Museum.

Fig. 9. Decoration items of the last stone age. By Montelius, Klebs and Johann Ranke

In artistic terms, our attention is primarily worthy of the dwellings of these people of the later Stone Age, due to its usually round, and sometimes rectangular, pits that constitute the transition from the caves to detached huts. In Germany, such "underground dwellings-pits", as Görnes calls them, whose roof rested above the ground on low pillars, are discovered mainly in Mecklenburg and South Bavaria, as well as near Worms. But also in Austria-Hungary, in France, England and Switzerland, they were also recognized as human dwellings of the Stone Age. We said above that they deserve attention because of their round shape. In fact, only the first weak signs of artistry can be seen in the construction, when the builder’s sense of space is expressed in the correctness of the basic outline. The famous Swedish explorer of prehistoric times, Montelius, believed that the most ancient huts of prehistoric times erected on earth were round. Montelius finds that the round shape, through the intermediary shapes of the square contour, on the one hand, and the oval contour, on the other, has become rectangular; the cone-shaped or pyramidal roof of a round or square hut, being erected above a rectangular hut, first climbed to all sides on all four sides, and then gradually turned into a sloping roof and only later - into a roof with a pediment. On land, there are no remains of such huts built of piles, clay and brushwood in the Stone Age, but, oddly enough, there are many of them in the depths of inland lakes and swamps that once formed the bottom of the lakes. These are remnants of prehistoric pile structures, remnants of once-existing water villages, which, connected by means of narrow walkways to the land, were kept on piles above the surface of the lake. Buildings of this kind, originally discovered in Swiss lakes by F. Keller, which described them in detail, were later found on the edges of the lakes of various countries of the Old and New Worlds. Along with the classic Swiss pile constructions, in Germany the pile constructions of the Starnbergersky and Barmsky lakes, as well as the Shussenridersky swamp are especially remarkable; in Austria - the buildings of the Attena and Mondsky lakes and the Laibach swamp.

Science generally refers to pile constructions as a later stone age, inasmuch as the most ancient of them really arose at that time and that in some places, for example, in most lakes of Eastern Switzerland and in the Austrian Alps, they disappear at the end of the stone age (copper period), which in relation to artistry is generally on the same level as the stone one. It should, however, now stipulate that even on Lake Zurich, in Vollisgofen, a pile structure was found, probably from the Bronze Age, that pile structures in Western Switzerland existed during the entire prehistoric metal period and that some primitive peoples of all parts of the world have still and still represent the predominant type of structures.

According to the structure of the huts, there are two systems of pile structures: pile structures in the true sense of the word, typical of which is Roberghausen, in Switzerland, and buildings located on Packwerkbau logs piled on top of each other, in Niderwil. In these pile constructions, the piles that supported the entire structure were driven into the bottom of the lake so that they protruded one or two meters from the water. The piles on top were joined together by transverse beams inserted into them, and the latter, to form a deck or a platform, were connected by two rows of wooden bars superimposed on each other. The essence of another kind of construction was that the rows of beams or logs superimposed one on top of another along and across, forming a raft on which new beams were put when the tree, soaked with water, began to descend; pile up beams continued until the entire lower part of the structure fell to the bottom.

On the platform of pile constructions of alpine lakes, each individual hut was placed on a hard floor made of yellow clay; The very method of building a hut and building a roof probably did not differ from what was used in buildings on land. From the remains, it was possible to determine more than once that the walls were woven from twigs, and outside they were coated with clay, on the layer of which geometric decorative patterns were then squeezed out.

Tectonics, carpentry, and at the same time European house-building, obviously, should be considered as one of their first major successes these pile structures, of which the most ancient ones appeared to be thought to be thousands of years seven years ago. To the question why such buildings were constructed, the question that was repeatedly proposed and received very different solutions, we can, for our part, referring to the pile constructions of many primitive peoples of our time, to answer that they were forced to settle above the surface of the water. , many reasons combined. The main ones, apparently, were, firstly, the need to defend themselves from land animals, not only four-legged animals, but also snakes, and secondly, the convenience of catching fish and killing animals that came to the beach to quench their thirst. These reasons, perhaps, were joined by the need for cleanliness and, finally, the pleasure to live above the transparent green waters.

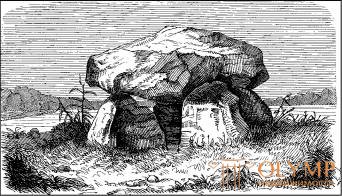

Fig. 10. South Swedish dolmen. By montelius

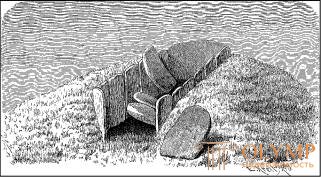

Along with these remnants of the dwellings of people of the later Stone Age, we get to know the tombs, namely, the graves of knights (Hbnengrflber), and other megalithic, that is, built of huge stones, tombs. We do not go into the question of whether these tombs and tombs arose in imitation of the cave tombs of other times and countries, as Sophus Muller believes, and whether in this case it is necessary to consider them as artificial depressions made in the rocks. If pile constructions are naturally in the geographic region of standing water, then megalithic tombs, in some areas existing even in the metal epoch, are found where there are powerful rocks. If we see the rudiments of wooden architecture in pile constructions, then in the megalithic monuments we see the first attempts at building stone with stone, and although this art has not yet been able to erect something truly artistic from huge, almost uncouth boulders, it already comes to understanding the law of maintaining and piling up in its monumental simplicity, with strength being calculated for eternal times, and the powerful tension of forces, expressed in the piling up of giant stones on each other, is devoted to the pious in spominaniyam and indicates that the heroes of antiquity, formed the flesh of our flesh, there were animated by exactly the same feelings which are peculiar to us.

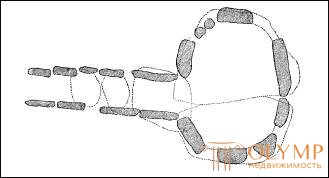

Grave structures are divided into dolmens (dolmen), graves with tunnels and graves in the form of stone boxes. Actually dolmens (Fig. 10) are free-standing grave structures: huge, sometimes slightly smoothed inside, and outside the unhewn stones form walls of four-sided, multi-faceted or nearly round grave structures; their flat roof is one huge stone, sometimes projecting far above the walls, as a result of which such a structure has the appearance of a giant table. In the north, tombs-dolmens of this kind were surrounded by earthen mounds, which have disappeared in our time. The tombs with the passages were built in the same way, but they are more spacious and covered with a bulky earthen hill, on the surface of which the ceiling stones of the inner chamber initially lay open, and the covered stone passage led from the outside (fig. 11). Large graves of this kind in the north are called "giants' rooms." “Stone boxes” are similar grave chambers, but without leading passages (fig. 12). In ancient times, in Sweden, they usually stood out from their earthen hill, poured on them, in their bronze epoch completely hidden under it. According to Scandinavian scientists, dolmens are the most ancient, and stone boxes are the latest forms of megalithic tombs. Tombs with passages that form gigantic rooms are found in addition to the northwestern part of the European continent in England, Ireland and the Iberian Peninsula. The largest structure of its kind in Northern Europe is located near New Grange, in Ireland. Even more significant is the Antekver stone grave in Spain. Having a length of 25 meters and a width of 6 meters, this grave is supported inside by pillars, which give it the character of a building of the highest rank.

Fig. 11. Tomb with a passage into it, near Falköping. By montelius

Along with real dolmens, which were sometimes only monuments in honor of the dead, there were less complex stone heaps (Steinsetzungen) and often simple pillars that can be viewed as historical monuments or as symbols of religious ideas. The desire to put stones to perpetuate any event was everywhere before the ability to create architectural or sculptural works of art from stones. Some stones of this kind, which are very often found in France, are known under the Gallic name menhir, while the groups of menhirs are called cromlechs. Menhirs, sometimes reaching enormous heights, resemble coarsely hewn obelisks of irregular shape. They are often found in groups or in the form of rows and circles. On the Karnak field, in the Morbigan Department of France, 11,000 of these menhirs, standing in eleven rows, stood, or more recently, a whole army of dumb witnesses to the powerful manifestation of forces that moved something higher than the daily needs of man and which carried him to the spiritual world of unearthly ideas. Каменные круги в Скандинавии, во Франции и Англии всегда опоясывали священные пространства, служившие, с одной стороны, для совещательных собраний, с другой – для жертвоприношений и иных религиозных действий. Еще каменному веку, по-видимому, принадлежал, например, самый обширный из так называемых "храмов друидов" в Англии, а именно окруженное валом и рвом круглое строение в Абюри, в Вильтшире, занимавшее собой площадь в 281/2 моргов.

Fig. 12. Могильный склеп в виде ящика. По Монтелиусу

Starting from southern Sweden, Denmark and mainly from South-West Germany, where the huge boulders left by the ice age, they naturally suggested that they be collected and piled on top of each other, dolmens and stone monuments stretch across hundreds of thousands of people across England and Ireland. Western France (Normandy and Brittany), from here, across northern Spain along the coast of Portugal, go into southern Spain, then, passing the sea, they are found in North Africa and across the African coast of the Mediterranean, then appear in the Crimea and Palestine, and finally in India, especially on its western coast, while within land, if they come across, it is only alone, in the space between the Baltic Sea and the Crimea, on the routes connecting East and West. It was previously thought that these are border stones that mark the path of the Aryans from India to Northern Europe.Krause wittily defended the opinion that the stones in question, on the contrary, indicate the path of Aryan tribes from Northern Europe throughout their current distribution area, up to India. But the correctness of neither one nor the other view can not be proved. In the end, megalithic structures also belong to manifestations of human forces, repeated under the same conditions among different peoples.

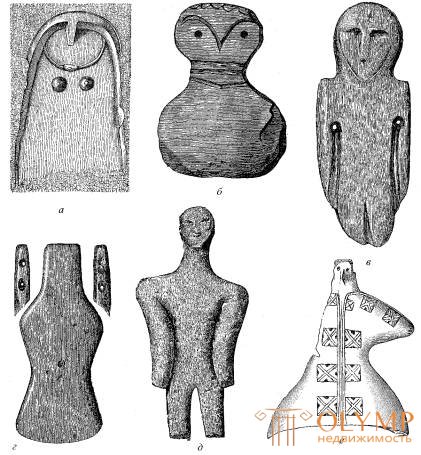

Fig. 13. Neolithic figures of people. By Kartalyak, Schliemann, Tischler, Klebs and Ranke

Sculpting and drawing did not achieve such successes as architecture in the later stone age. We even have to admit that the ability to depict animals and people has taken a step back. Some of the surviving scrawled drawings of the Neolithic era, such as the two fallow deer depicted on a horn found near Ystad and stored in the Stockholm Museum, and two deer heads on bone plates found in Franconian caves and preserved in the Munich Prehistoric Museum are like offshoots of diluvial cave art. But in most cases it is only possible to talk about inept new attempts.

On megalithic structures in France and Portugal there are semi-plastic shapes of figures on the stone. Particularly typical are female figures and, probably, figures of gods with childish outlines found in French grave chambers always to the left of the entrance, mainly in artificial grave caves of the chalk Champagne cliffs, which are a cross between natural grave caves and megalithic grave chambers. About the dismemberment of the body of these figures, the designation of their arms and legs, there can be no question. A flat, recessed niche forms a body, its upper semicircular top is roundness of the head. The hair and forehead are indicated by the rim of this upper round, serving as a bulge. From her nose drops down into a flat space, on the sides of which the eyes are set in the form of points. Only in some cases the mouth is marked with one or two thin lines; the neck is usually marked with a simple chain that serves as an ornament; below are sometimes marked breasts in the form of prominent curves (Fig. 13, a).

Other works of the same or a similar stage in the development of art have the same type. Here one has to point out the prehistoric marble idols and vases with persons found along with bronze objects; similar idols and vases were found by Schliemann in the second and third layers of Hisarlik and donated by this researcher to the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (Fig. 13, b). The amber figure (fig. 13, c) of the Stone Age in East Prussia, found in Schwarzort and stored in the Königsberg Museum, is fully included here. The same stage of development generates the same forms everywhere.

We have a lot of small plastic images of humans and animals from the later stone age. Not to mention the works of the later blooming period of Greek art, we note that the figures are found almost only in the eastern part of Central Europe. Among them, a nude female figure prevails, from which, too, this time the artistic movement takes its origin (see Fig. 5). Remarkable are the sedentary nude female figures with strongly developed lower parts of the body and with scratched ornaments, originating from the outskirts of the Philippopolis and stored in the Vienna Court Museum; No less curious are female clay figures from Cucuteni, in Romania, with flat breasts and with buttons-like heads, but with well-developed hips, covered and covered with spiral scratches along and across that resemble a tattoo. More shapeless, but with a more careful decoration of the heads, are numerous small clay figures from Butmir, near Sarajevo, in Bosnia, in whose museum they can be studied. Still small-headed, clay-clad figures from the Laibach swamp, clothed in wide clothing belong to the Stone Age, while the images of animals from the pile structure in Lake of Mondia already belong to the Copper Age. Along with attempts at realism, at the very beginning, there is a desire to depict people in the form of regular geometric shapes and bodies. The amber figure from Kruhlinenna, the Koenigsberg Museum (Fig. 13, d), which belongs to the newest stone age, shows how a rectangular shape of a human figure gradually forms from a rectangular shape by narrowing it in the middle and adding a neck; The same kind of education can be assumed in the clay sculpture from the Laibach swamp, which is stored in Rudolfinum, in Laibach, and remarkable in its patterned clothing (Fig. 13, f). Some of the bones found in Polish caves, between Krakow and Czestochowa, belong to the realistic attempts of the Stone Age, in particular, the broad-shouldered figures in the collection of the Krakow Academy of Sciences (Fig. 13, e) are worthy of attention.

However, it should be noted that the Neolithic human figures, which we can recognize as idols or talismans, despite the commonness of all of them, are different in each particular place of finds, have their own specific type, so that we cannot consider them to be simple reflections of the Aegean-Mycenaean world of art, the type of which they are only partly suitable, although they are found in Southeastern Europe more often than in Northern and Western.

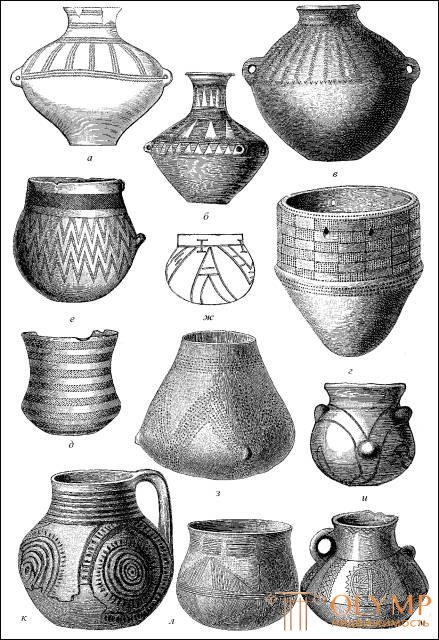

The Europeans of the cultural stage of the later Stone Age are artisan craftsmen primarily in pottery (ceramics). Here before us are really the rudiments of development going on up to the present. In the huge number of earthen vessels belonging to the Stone Age and decorated pottery shards, accumulated during the XIX century in the prehistoric collections of all European countries, first of all, it is impossible to recognize the striking uniformity of the basic character of both technique and ornamentation. But, at the same time, the differences of one of these products from others are no less obvious, depending on the fact that the development of the art of their production took place in different localities and not at the same time. An extensive scientific work aimed at clearing, grouping, interpreting and comparing all the material accumulated in this part has just been begun. For Central and East Germany, much has already been done in this direction by Virkhov, Tischler, Voss, Brummer, especially Klopflesish and Goetze; Lindenshmit, Wagner, and Könen are important for the Rhineland. In this book, we can point out only some of the main conclusions based on the studies of Klopflesch and Goetze.

The whole pottery industry of the Stone Age was unfamiliar with burning on the fire and decorating the vessels with geometric linear patterns, which before burning were pressed into the soft clay, punctured or cut into it and usually filled with white plaster mass. In Central Germany, for example, the strict and beautiful forms of amphoras and cups develop into more round, less dissected forms of pots and jans, and small handles, openings for a cord, on which a vessel is worn and hanged, turn into such handles that you can grasp , the indented decorative lines become impaled or embedded, straight lines - into twisting and rounded curves.

First of all - a few words about embossed jewelry. They begin with simple indentations with a finger in still wet clay. Repeating around the circumference of the vessel at the same height, these dents form rings, the irregularity of which largely enlivens the impression of individual parts of the overall ornamentation. More rigorous geometric figures are obtained by drawing with nails. Similar speckled ornaments, but already correct, are made with rounded sticks. Many samples of such products are found in pile structures. But the beloved depressed ornament turned out to be an impression of the ropes, which, perhaps, still soft at first, the vessel was tied up before firing. Such decoration with cords, stretched in the form of three rows of parallel lines, with vertical intermediate lines, we see on the beautiful Thuringian amphora, located in the provincial museum in Halle (Fig. 14, a).

Fig. 14. Neolithic ceramics. According to Goetze, Klopfleish, Montelius, Andrian, Ranke and Mucha

The lines of imprinted jewelery consist of points located close to one another, the shape of which depended on those used for impaling the bone tip of a wooden chip or reed. On a large urn from Bodman on Lake Constance, which is kept in the Rozgarten Museum, in Constance, the dented triangular figures, impaled, apparently, by a piece of trihedral reed, are correctly repeated. Threaded straight lines, in essence representing the most natural bases of geometric patterns, are often found in Neolithic ceramics as borders of cords or spaces, the shading of which consists of pricks. In fig. 14, b, depicts a beautiful amphora-pitcher, found in the duchy of Weimar, stored in the German Museum, in Jena, on it pinned zigzags are surrounded by a border of rifled lines. In fig. 14, c, is a vessel with rifled ornaments and depressed triangles, found in Saxony and located in the gymnasium collection in Sangerhausen. In the Swedish hanging vessel (Fig. 14, d) we see something like a pattern of a chessboard (Stockholm Museum). If a line that serves as a rod or an edge joins lines that meet at an obtuse angle (in the form of rafters), an ornament is formed, which is called differently: spruce branch, fish bone, bird feather and fern pattern. It is possible that the idea of such patterns inspired a person to observe these and similar objects of nature. All the above-mentioned patterns of the most ancient rectilinear neolithic ceramics are so geometrically simple, so convenient for execution, that there is no reason to attribute any symbolic meaning to them.

All these ceramics, adorned with pressed-in cords, chops and rifling, can be opposed to ceramics found in some places near it, but mostly later and different from it by other ornamentation, which Klopfleish called the "Neolithic ribbon ceramics ornament". While the vessels we have examined so far have been found in tombs, pots of carefully washed clay, mostly round or egg-shaped, with ribbon ornaments were found mainly in the remains of dwellings of the Stone Age. The elements of their ornamentation consist of variously winding ribbons, bounded by deep parallel lines; these ribbons often, fluttering as if on the loose, are only “reluctantly subject to the law of symmetry,” and sometimes as if attached to bulges or warts, which later appear in the ornament in later times. Along with these angled ribbon ornaments, in which the complications of the meander pattern are observed (Fig. 15), there are arcuate tape twists, in which sometimes are the rudiments of volutes (the cochlear line) and the spiral shape. Near Worms, in the tombs, pots with angular ribbon decorations were found, and pots with arc-shaped ribbon decorations were found in the dwellings. Examples of ribbon ornaments that form corners or arcs are seen in the pots shown in Fig. 14, w and and. The first of these pots was found near Sondershausen, the second in the Weimar Grand Duchy. Both are now, apparently, in private hands. The centerpiece of this ceramics was Bohemia, and to the south it is found mainly in Bosnia. Further research in the field of neolithic pottery is likely to clarify even better the historical stages of its development.

Fig. 15. Diagram of the meander

Ornamental stripes are usually considered to be broken or curved in the same way decorative stripes, which, being devoid of curb lines, cannot be considered ribbons in the true sense of the word, but consist of impressed or scratched parallel lines that are closely pulled together. These include decorations of some neolithic vessels of Sicily, such as, for example, those taken from the Villafrati cave and stored in the national museum in Palermo (Fig. 14, e); decorative patterns of vessels dug by Lindenshmit on Ginkelstein, in the Rhine Hesse, and stored in the Mainz Museum (fig. 14, l and l) should be referred in particular here. In our opinion, these vases found in the graves are located in the middle between the vessels with impaled and scratched ornament and pots of the second kind we considered, with ribbon ceramics.

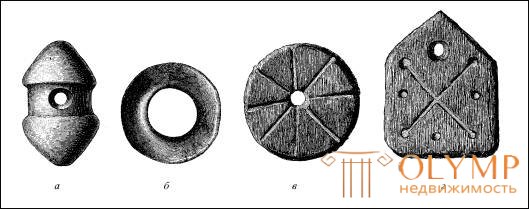

Since, staying on the Central German soil, we assume, together with Klopfleshim and Goetz, that the vessels with ribbon ornaments belong to the later Neolithic era, then we will have to admit that the vessels from the Laibach swamp (Fig. 14, m) stored in Rudolfinum, Laibach , Johanneum, Graz, and the Natural History Museum in Vienna, where crosses and circles filled with patterns appear among the spaces bordered with ribbons, signify further successes made in the mentioned era; The same can be said about the vessels extracted from the pile structures of Lake Monde, which abound with copper utensils, along with even more stone utensils, which is why it is now possible to assert, together with the Viennese researcher Mukh, who found these vessels, and their owner, and also with Gampel and others, that there existed a special copper epoch, a forerunner of the metal epoch, but according to the degree at which her art stood, which dates from the end of the later stone one. On vessels from Lake of Monde, ribbon decorations appear in conjunction with shaded triangles and quadrangles, with concentric circles, "sun wheels", crosses, even with real spirals, sometimes forming a beautiful, sometimes somewhat strange-looking whole (Fig. 14, k). Although the technique of decorative lines scribbled and filled with white paint, drawn against a dark background, has not changed here, and the patterns still consist of a strictly geometric combination of lines, but we already feel the flow of a new, different time. We cannot give an answer to the question of the symbolic meaning of many of the individual signs, but we cannot also say that this question does not have the right to be raised. We must even recognize here the possibility of the influence of the distant eastern countries, which appeared along with copper. Remarkably pointed out by the Fly is the exact similarity of the technique and decorative motifs of some pots found in the Lake of Mondas to the techniques and ornamentation of vessels and shards from the lower prehistoric settlement of Troy and the excavations on the island of Cyprus - vessels belonging to, like the pile epochs of the Lake of Mond, stone age already familiar with copper. The peculiarity of some patterns on those and other monuments does not allow the assumption that the ornamentation of some and the ornamentation of others arise independently of each other, and everything indicates that the borrowing party here, in all likelihood, was not the Mediterranean Sea, but Lake of Mondas.

This spiral, which we have already met on the Paleolithic finds, was not a product of the metal age. This is proved by the fact that it comes across on many Neolithic vessels primarily in conjunction with developed ribbon ornamentation, for example, on earthen vessels found in Butmir, in Bosnia. The spiral does not belong to those decorative motifs that could not be borrowed from nature independently of each other.

Painted earthen vessels of the later Stone Age are a great rarity. In the south they appeared earlier than in the north. Here, in Lower Austria and Moravia, the first experiments of polychrome flat images on Neolithic pots and bowls were found. Palliardi unveiled painted vessels from Tsnaim; On them white, yellow, brown and red earthen paints are covered with ribbon-like, trellis, spiral and acute-angled ornaments. The vessels of the later stone age, painted in red by glanders or iron ocher, were found only recently also in the Vorm region, near the Rhine.

As a semi-plastic increase to earthen vessels of the Stone Age, sketches of human faces on pots from Funen, Zeeland and Shonen stored in Scandinavian collections are important. These faces are connected with two handles protruding from the vessel (griff-shaped ears) and, as Sophus Muller suggests, arose due to the fact that a technically necessary component of the vessels was given, for fun, a different meaning. On the round ear, eyes were pricked or naked. The gap, which served as a pen, became a nose. Mouth was not here.

While prehistoric scholars tend to think that human figures or body parts have evolved from geometric figures or inanimate parts of one or another utensil, ethnologists insist that most of the geometric figures they dealt with come from human or animal figures. However, it is also possible that prehistoric art went one way or another, and we can agree with Karl von den Steinen, who produces geometrical ornamentation of some primitive Brazilian peoples from objects of nature, but disagree with him when recognizes a decorative motif, already known

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)