In the skill bee will instruct you

And diligence will teach the worm of the valleys;

But knowing your mind with spirits nearby puts:

Art, man, you have one.

Schiller Artists

The name "History of Art" in the language of science is understood as the history of the development of those arts whose works are created by the hand of a master and are perceived by the eye. Usually, these arts, which include architecture, the production of exquisite handicraft products, sculpture and painting with their secondary branches are called "figurative arts". In view of the fact that the works of these arts are mostly performed according to preliminary drawn sketches and can be depicted by drawings, they are also called “descriptive arts”.

The history of art certifies that it is the property of all mankind; This is a spiritual connection uniting even the most remote times and nations. Not to mention those stages of development, about which we can only speculate, there is not so far from us in time or place the cultural stage, which would not be lit up with a bright ray of art that distinguishes man from animals. In the most ancient, primitive times, as well as among the most distant and low-standing peoples still living on earth, we see that a person driven by love not only seeks to adorn himself, not only tries to give his simple utensils the most convenient and appropriate, and to supply this utensils with decorations, but also trying to create plastic or inscribed images of the existing in the surrounding world, especially in the world of animals and people, and this art of primitive and wild peoples often in unexpected ways It broadcasts to us the inner, root essence of art. Modern art history can not neglect the study of its condition in simple, primitive peoples and in prehistoric, primitive tribes. Since Ernst Grosse pointed out in a special book the need for such a study, the history of art is more and more seriously engaged in primitive life and prehistoric times of mankind, and by the end of the XIX century it can be said that this science embraced the art of all mankind.

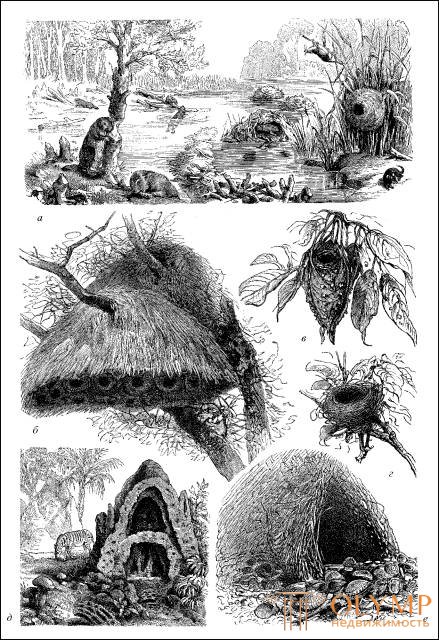

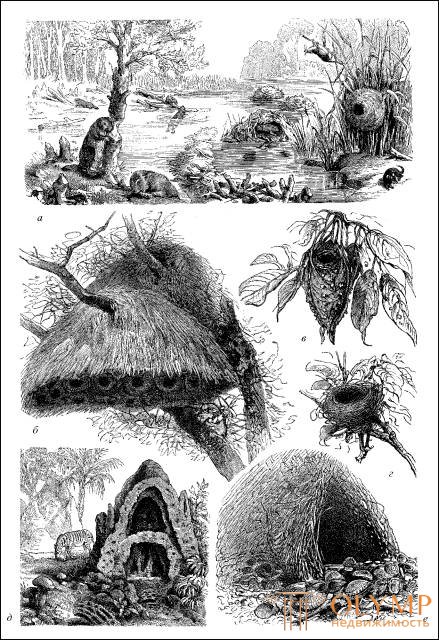

Fig. 1. "Art" in animals: a - dwellings of a beaver and a dwarf mouse; b - colony of weaver's nests; in - the dressmaker's nest; g - nest of Slav; d - construction of termites in the section; e - entertainment hut Australian hut. Drawings of Heinrich Moren from life

Convinced of the need to study primitive art, we unwittingly ask ourselves the question: should we, to understand his real beginnings, take another one further step and look for whether these beginnings already exist in the animal world, in natural history, to which to resort to clarify the first steps of history in general and questions of ethnology? The question arises: do not other creatures, besides humans, possess a real desire for art, do they reveal this desire? - and most importantly, do we have the right to believe that for animals endowed with much more subtle external senses than we are and We feel in a state of wakefulness, and in a dream, pleasant and unpleasant sensations - once and for all close the earthly paradise of artistic creativity and enjoyment of art? To answer this question is not as easy as it may seem at first glance. If we remember that already old researchers, such as Rennie and Garting, and that scientists such as Wood, Büchner and Romanes, recently recently, examined the question of animals' striving for art, we understand that before moving on, we need to familiarize ourselves with the views of these scientists and find out to what extent in the actual or perceived desire of animals for art it is permissible to see a preliminary step towards human artistic activity.

It is known that animals, like people, have a propensity for games, which others consider to be the initial desire for any artistic exercise; but the propensity to play and the pursuit of art are similar only to the fact that both of them suggest a certain excess of strength after satisfying the needs necessary to sustain the life of an individual or a whole species. Both express the need for rest, for free activity after labor. If we recognize that art in our sense begins only with such creative activity that gives tangible and visible results, we will see a very big difference between this desire for games and the true desire for art.

The right question will be the following: are there any animals that, for their own pleasure or for the pleasure of others, display a conscious or unconscious ability to create? There is no denying that to some extent the singing of many of the birds can be attributed. Rhythm and melodiousness in the singing of the nightingale seem to be the basis of all music, and that these fundamentals are the same for both the bird's and the human ear, for example, bullfinchs, who, with proper training, get used to whistling arias composed by humans, and retain their rhythm and tone.

But in the field of figurative arts, the situation is somewhat different. In animals we never find the slightest attempt at sculpting or painting - in other words, we do not find an exercise that would be directed towards the reproduction of visible objects. Consequently, these areas of art, in many respects the most important and essential, are completely inaccessible to animals. But the architecture produced by some animals is often so striking that it can shake established notions about the differences in the abilities of people and animals.

As you know, many insects achieve amazing results when building their homes. First of all, we point out wasps and bees, especially bees living in hives. The honeycombs and cells for raising young offspring and for collecting honey stores are built by these insects from homemade wax. These are amazingly clever structures. What order, what prudent allocation of space in each piece of cells! What is the correctness in each cell composed of six almost equal faces with a pyramidal bottom! Then we turn our attention to the ants, whose dwelling seems to be outside, though only as an irregular heap, but sometimes extends inside several meters below the soil surface and is an extremely clever building consisting of 30-40 floors one above the other. How hard it is for these tiny animals to carry their building materials made up of pieces of wood, knots, grass stalks, pebbles and needles of coniferous trees! How carefully the individual floors are backed up with pillars and crossbeams, sometimes up to 10 or more centimeters long! How skillfully strengthened, with the help of intersecting beams, the ceiling of a large hall located in the middle of the maze! African termites deserve special attention because they create themselves with the common forces of a dwelling height of up to 6 meters with cone-shaped roofs (Fig. 1, a). Many travelers, seeing these buildings from afar, mixed them with the round huts of the neighboring Negro tribes, because the buildings of termites often exceed their human dwellings and are always better built and trimmed inside. Their walls, molded from earth, clay, pebbles and plant parts with the help of sticky saliva secreted by termites, form a solid, solid mass that can protect all internal passages, rooms, chambers and rooms used for all possible, predetermined purposes from any external damage. public life named insects.

Perhaps even more striking are the structures of some rodents, for example, a dwarf mouse, which hangs its round nests woven from small stalks to the reeds (Fig. 1, a); but the beaver, at least North American, is especially remarkable in this respect; it builds a dwelling of sticks, brushwood, and silt near the water, on the edge of the coast (see Fig. 1, a). A beaver's almost round or oval hut towers like a flat dome; of the two entrances to it, having the appearance of irregular arches, one goes so deep into the water that it does not freeze even in the most severe winters. Even more amazing hut beaver on the ground of his construction in the water. To maintain a constant water level near their dwellings, beavers arrange artificial ponds, fencing them off with real dams from higher-level waters, and fill them with water using structures resembling gateways and long canals. In North America, dams of approximately 200 meters in length have been observed, arranged by the aggregate labor of countless beaver generations. No other animal buildings are so similar to human buildings as these buildings.

But the most remarkable architects in the animal world are some breeds of birds. One can trace a whole series of feathered art steps, from simple and irregular nests of some (fig. 1, d) to perfectly executed, so to speak super-animal constructions of others. An Indian weaver, whose nests, according to Darwin, "almost surpass the weaving of men," builds his hanging dwelling out of real fabric made of solid stems, sometimes even arranging upper and lower rooms; weavers' breeding birds in South Africa, their huge nest palaces that serve as shelters for entire societies, hang them to the branches of trees (Fig. 1, b), and dressmakers of various types sew their nests from large leaves according to all the rules of art (Fig. 1 , c), whereby they use vegetable fibers or randomly found human-made threads; they even say that, at the beginning of work, they attach these threads through nodules. The long-tailed dressmaker, found in India, she spins cotton threads herself, working with her beak and claws; Italian dressmaker uses the web for the same purpose, having processed it in a known manner. The greatest resemblance to a person, however, is represented by various kinds of Australian huts, constructing "pleasure huts", or "houses for games", which, apparently, do not even serve them as dwellings. These huts are completely different in shape. Take a closer look at the Ptilonorhynchus holoseriscus dance hall (Fig. 1, f)! Light, slightly arched passages, such as gazebos, are attached to the floor, which consists of tightly intertwined branches, with the long sides of these gazebos completely closed and the short sides open. These arches are intertwined from thin rods, the ramifications of which are always directed outwards so that there are no irregularities inside. Pergolas are always ornamented; especially the entrances are laid out in the brightest and most variegated decorations that birds can find. The motley feathers of other birds, patches of colored matter, products of human hands, shiny pebbles and snail shells are partly laid out between knots, some are scattered on the ground in front of the entrance. If these amusement houses, usually built by males, according to most naturalists who observed the life of herders, are built only to attract females, then you can still say that these huts would not reach the goal, if the birds didn’t enjoy such motley creatures of their imagination . Therefore, supporters of the Darwinian theory of development refer to the entertainment houses of Australian bowerboys more than anything else to prove that the desire for art, like all other human properties, is also observed in creatures that are much lower than it.

We do not intend to warn the conclusions of researchers in this field and are ready to admit that in some of these phenomena in the life of animals, a striving close to the human desire for art is noticed. But this does not prevent us from looking at this so-called animal art from our own point of view. First of all, we must not forget that all the examples cited as proof of the animal's inclination to art constitute only exceptions and that, in the field of arts perceived by sight, the desire for games and for the preservation of the form, probably, only among tents is a real desire. to art. This exception should be even more relevant to the exceptions confirming the general rule that monkeys, animals, most similar to humans, do not show the slightest ability to art, despite their tendency to imitate.

But even the “architecture” of animals in the vast majority of cases only serves to satisfy their need for protection, nutrition and reproduction. Their buildings are purely utilitarian structures, which usually do not even represent the basic principles of artistic proportionality, without which the structures of the person himself cannot be recognized as art. The laws of correctness, symmetry, proportionality, if at all, are observed, then only approximately and by chance. Absolutely round places for games and nests in some birds can be considered as a real exception, although the round shape is obtained here in a completely natural way and unintentionally from the movement of animals around themselves. In this respect, the only apparent exception is the hexagonal cells of the bees. The most thorough naturalists, praising the correctness of bee cells, recognize, however, that on the question of their construction there can be no talk of the conscious or unconscious intention of bees for their own pleasure to observe a mathematically correct form. The bees, according to Büchner, tend, apparently, only to stick "as many cells as possible with as little wax, space and labor as possible", which is best achieved with a hexagonal shape and a pyramidal bottom of the cells. Wit Graber even assumes that the initial shape of the cells is rather cylindrical and that they only take on the correct prismatic shape only because of pressure on one another.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the works of art of various animals of the same species — if you can even talk about such works in animals — never bear an independent imprint on themselves that is different from the creatures of the creatures like them, but always just repeat, according to to the blind, nature-inspired impulse, what millions of similar animals have done in exactly the same way for thousands of years; therefore, the development of art in animals, even though this development should have taken place in ancient times, cannot be spoken of, since freedom of creativity is an essential condition of art.

The ability of animals to create, on occasion, the correct forms is no more than a particular manifestation of the artistic force of nature, which in the world of minerals and plants still generates in a much more surprising way the correct play of lines of geometric ornamentation adopted by man. Ornamentation is the ABC of art history, and we must first stop our attention on it. We will think only about the shape of crystals, snowflakes, petrified ammonites, ekhinites and belemnites, think about the proper formation of many leaves, flower cups and stalk cuts, remember what amazing, sometimes mathematically correct drawings of nature created some of the lower animals.

Let's not deny that nature is the greatest artist. But since we oppose art, as a special concept, to nature, it presupposes free human activity, the history of which can be traced. About art, allowing its history, we can say with the poet: "Art, man, you have one."

The basis for the manifestation of the forms of this human art is the concept of space, which, as we know, Kant considered natural for man. The condition for any artistic beauty is to consider the requirement that the space filled with the work, its general form and its constituent parts make a pleasant impression on our feelings. A work of art excites an impression the more artistic, the more lively, freer and more precise it corresponds to the actually existing or mentally-drawn space, the more it answers to the laws of space proportioning, symmetry, correctness, balance, simple or rhythmic sequence that distributes space. But our eye perceives the forms of space only with the help of light, and the dismemberment of light, according to Newton's teachings, gives color.Only light and colors, combined with form, give the work of art that full, warm vitality, which through the eyes acts on our heart.

Содержание всего человеческого искусства составляет сам человек, который для себя есть мерило всех вещей. В средоточии своих художественных сооружений он ищет самого себя или своих богов, созданных им по его собственным образу и подобию. Его личные потребности, будничные или праздничные, его многоразличные действия и поступки находят себе художественное выражение в изящных ремеслах. Изображение подобных себе в ваянии и живописи является для него целью. Ваяние наиболее непосредственным образом изображает его ради него самого, в живописи же в наибольшей полноте выражаются человеческие отношения. И в ней человек видит все лишь в освещении своего помысла и собственных деяний. В мире животных он усматривает свою духовную жизнь, он влагает ее в пейзаж, если изображает его художественно. Мечтания его фантазии отражаются в сочиняемых им сказках. Вера в искупляющие божества доставляет содержание его религиозному искусству. То, что для него наиболее свято в жизни, воодушевляет его для создания величайших художественных произведений. Так или иначе, он по собственной мерке создает в своем искусстве новый мир, дабы укрываться в него от сутолоки и ничтожества обыденной жизни.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)