Architecture

North Italian, especially Lombard, architects early took an independent part in the development of Christian architecture. In the transition to the Gothic style, the Cistercian Abbey of Chiaravalle near Milan was built. But the real Gothic and here penetrated because of the Alps. The oldest Gothic church of Sant Andrea in Vercelli (1219–1224 and later) in Upper Italy, with its expansion arches outside and with beam posts inside, indicates a direct transfer of style from Paris. But the Upper Italian churches of the mendicant orders, which here are the conductors of the high Gothic, are less likely to find Tuscan than directly French influence. And here they have sometimes a flat covering or open rafters, sometimes vaulted. The earliest, all covered with arches Franciscan church of San Francesco in Bologna (1246–1261) with six cross vaults of the middle nave, a choral detour with a crown of chapels and octagonal beam columns seems to be transferred from Burgundy. But in this church expansion arches are added later. Similar device choir (1267) has a famous church of St.. Anthony in Padua (1232–1307). The combination of the Gothic choir and crown chapel with the dome system of the church of Sts. Mark in Venice, above the longitudinal body and transept. The six main squares topped with domes have semicircular arches; the arcades of the side aisles and the windows already use a pointed arch. The general impression is harmed by the lack of internal unity, but the building cannot be denied picturesqueness and impressive dimensions.

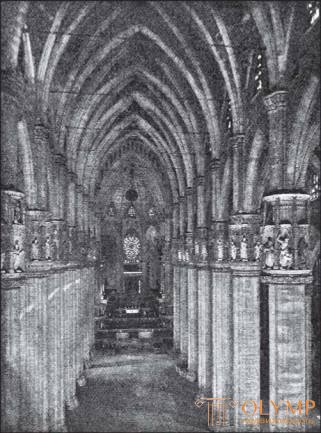

Many Upper Italian churches of mendicant orders took as a model the Tuscan type with a number of chapels on the back wall of the transept. However, the rectangular end of the choir is less common here than the performing polygonal. The Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pavia, composed of square sections, with straight choir chapels and calmly dissected pillars, is distinguished by a special clarity of the plan. Among the churches of the Venetian region, dominated by polygonal chapel ends and widely spaced round pillars, some still have a flat ceiling. The exemplary vaulted buildings of this genus, the interior of which, besides the polygonal end chapels, strikingly resemble the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, are the Franciscan Church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari (started in 1330) and the Dominican Church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo (started in 1333, Fig. 305), both in Venice. The history of their structures investigated Tode. These are simple large buildings that have become temples of art thanks to the works of sculpture and painting, which they were decorated with over the centuries.

Fig. 305. The interior of the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. With photos Alinari

A special place is occupied by the magnificent church of Certosa (the Carthusian monastery) near Pavia, begun in 1396 at the behest of the Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti; The history of its construction introduces the study of L. Beltrami. Along the three-nave longitudinal hull the rows of chapels stretch, making it look like a five-nave. The transept and the choir have the form of three completely identical wings, arranged according to the type of central structures, and each has an ending in the form of a clover leaf. The pillars are dissected, as in Gothic, the arches are pointed, but in arcades and naves they often again have a semicircular shape. However, this return to the semicircular arch here should be understood not as a restoration of the Romanesque style, but as a transition to the semicircular arch of the early Renaissance, in the style of which the magnificent main facade of this church and its other facades were later executed.

The facades of most of the Gothic churches of Upper Italy are dominated by brick style (the works of H. Shtrak and L. Gruner are devoted to him). However, the brick here is often animated by marble. The most beautiful gothic facade of Venice is the western facade of the church of Santa Maria del Orto; its lateral aisles also open to the west with magnificent pointed windows under graceful pointed arched friezes and rows of niches with statues. Of the Veronian churches, the most elegant Gothic façade of brick and marble has the small single-nave church of San Fermo. But in its purest form, this rich brick style, in essence Lombard-Romanesque, but replacing the semicircular arch of the pointed one, can be seen on the facade of the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pavia. The charming facade of San Francesco in Bologna with terracotta and majolica decorations had a great influence on Upper Italian architecture. In the marble facade of the Cathedral of Genoa, one can see the desire to adapt purely French motifs to the Old Pisanian alternation of rows of black and white stone; on the contrary, the elegantly dissected marble facade of the Cathedral of Monza clearly dates back to the brick facades.

The Gothic belfries of Upper Italy, although not always, but still quite often differ from their Romanesque types with lancet arched motifs; sometimes they turn into an octagonal shape and get a cone-shaped spire above the open top floor. An example is the tower of the San Gotardo church in Milan (1328–1379); her cheerful facing of red brick walls, alternating with white ashlar, characterizes this kind of buildings.

The two largest churches of Upper Italy are to some extent outside the general course of development and, by execution, belong to a part of the 15th century.

Church of sv. Petronius in Bologna, dedicated to the highly esteemed patron of Bologna, according to the plan of 1388, was to become the largest church in the world. But the building was discontinued in 1440, when the longitudinal case was barely ready, which still testifies to the ambitious plans of the 14th century Bolonians. The shape of the pillars, the arched spans, the general dismemberment of space borrowed from the longitudinal body of the Florence Cathedral (Fig. 306), but the proportions in the Bologna church are higher, more Gothic; extremely unsuccessful gallery on consoles deleted; and to the place of empty wall surfaces of the aisles, cut by narrow windows, there is a view of the double windows of the side chapels. Degio rightfully called this terminal part of the church of St.. Petronia is the most perfect interior in all Italian gothic.

Fig. 306. The building system of the church of sv. Petronia in Bologna (left) compared with the system of the Council of Florence (right). According to Bezold

The history of the construction of the Milan Cathedral can be found in the works of Camillo Boito, L. Beltrami and Alfred Gotthold Meyer. And here they set themselves the goal of creating a wonder of the world. Construction began in 1386 and by 1431 it was brought to the arches of the middle nave. But then even for whole centuries, separate parts of the cathedral were rebuilt, and the facade was completed only at the end of the 19th century. Milan Cathedral, which has a five-nave longitudinal body, crossed by a three-nave transept, and the end of the choir, formed by three sides of the octagon, with a detour, but without the crown of the chapel, according to the general plan and architecture with beam columns, buttresses and supporting arches, more closer to the northern Gothic than any other cathedral of italy. In terms of capacity it is the largest, in its material (white marble) - the most luxurious gothic church in the world. When the Italian architects could not cope with their task, German and French architects were called to help: Heinrich Parler from Gmünd, Ulrich von Enzingen, Miño from Paris, etc. In the end, with the help of Italian masters, the cross of the center crosses the building. The style of the Milan Cathedral, devoid of towers, can not be called purely French or German. It often affects the Italian taste, expressed in the predominance of horizontal lines over the vertical, but in its details a lot of new and original. New, in any case, capitals of pillars, consisting of statuettes arranged in a circle, although in this innovation it is impossible to see artistic success (Fig. 307); new for Italy was also the first time, probably applied in Bourges, and later the stepped lowering of the height of five naves, rooted in Spain, at which the inner side aisles occupy the middle between the outer and the middle aft. From the time of Burkardt, art criticism usually speaks very strictly about the Milan Cathedral. As for its appearance, distorted by subsequent centuries, where only the fabulous "marble mountains" can captivate our imagination, one should undoubtedly agree with these reviews. But the interior with high arches and a whole forest of pillars, with a reigning color twilight, poured - with later - painted glass windows, can not fail to charm an open-minded viewer.

Fig. 307. The interior of Milan Cathedral. With photos of Brodgy

The secular buildings of the Upper Italian Gothic cannot be compared in terms of monumentality and inner greatness with the Tuscan ones, but they surpass them in the luxury of their external decorations.

Fig. 308. Doge's Palace in Venice. With photos Alinari

A series of town halls opens the Palazzo Public of Cremona (1245) with its loggia, formed by six pointed arches. Exemplary building of this kind was the Palazzo Municipal in Piacenza (started in 1281). Its lower floor, built of sandstone, opens to the outside with a monumental gallery with five pointed arches on the pillars; the upper brick floor with ornaments of baked clay is cut by six triple windows in rich frames and surmounted by a jagged eaves protruding outward on the consoles. But the most famous and most majestic of the government palaces of Upper Italy is the Doge's Palace in Venice (Fig. 308). The façade facing the sea, which emerged between 1310 and 1340, served as a model for the façade facing Piazzetta and added in 1423–1438. The lower floor opens with wide pointed arcades on short, thick columns, they correspond to the double number of arcades of the upper floor with a luxurious through ornament, but narrower. The third and fourth upper floors rise in the form of smooth and smooth surfaces, lined with a simple pattern of rhombus and cut through a small number of windows. The heavy upper part of the building stands in the wrong ratios for both the lovely lower floors. This has been noticed many times and even more often is deprecated. But we must not forget that the reflection in the water, on which the oldest, southern facade was designed, significantly changes this ratio of parts.

Of the Upper Italian court buildings, the Palazzo della Radzhione in Padua (1192–1270) should be put in the first place, famous for its elegant two-story, still half Roman, loggia. Palazzo de Jureconsult in 1292 has a gothic appearance in Cremona with huge triple lancet-arched windows, a powerful arched frieze at the top, topped with battlements. Upper Italy has no public galleries like the Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi, nevertheless the two-arch Loggia dei Mercanti in Bologna (1332-1384), despite its closed upper, topped with battlements, the floor is perhaps the most graceful and rich brick Gothic building in all over Italy. Columns and carved window frames of white marble impart a weak colorful movement to it. Gothic residential buildings in significant numbers preserved in Upper Italy. The Palazzo Pepoli in Bologna, for example, shows what kind of Tuscan style of family castles gets with brick building material. But only Venetian apartment buildings of this epoch are really original and original. Bright, with a large number of windows, with pointed arches, the facades are often provided with galleries in the lower floor, and in the middle parts of all floors there are balconies with four or more, up to eight, with arched spans; they rise right above the mirror of the canals, their walls and columns sparkle with white marble and multi-colored rocks of stones; their foundations lay on piles driven into the soil of the lagoons; at the marble stairs of their main entrances stick gondolas. Gothic style continued to live here in the XIV century, and even the oldest buildings were preserved for the most part in the processing of this later time. Palazzo Contarini-Pheasant - one of the most charming brick unlined buildings of this kind. The huge Palazzo Foscari with a typically dissected marble facade is distinguished by the more free forms of the 15th century Gothic. Doro, who has preserved an open gallery of the lower floor from the old building, in its modern form (1424 and 1437), with a facade consisting of correctly alternating arcades and windows, may be the most delightful private building in the world.

Plastics

If in the previous epoch the Upper Italian sculpture took possession of Tuscany and Middle Italy, then in the period under review, as A. G. Meier, G. Biskaro and Diego Sant Ambrogio allow to conclude, such a strong flow from Tuscany to Upper Italy begins that this ratio becomes almost the opposite.

Milan in the reign of Visconti, Verona under the domination of the Scala dynasty, Venice in the flourishing time of the predominance of hereditary aristocracy were in Upper Italy the main cities of the artistic movement. The style of the Pisa school brought to Milan Giovanni di Balduccio. His surviving major work is the magnificent marble tomb of Peter the Martyr in the church of Sts. Evstorgiya (S. Eustorgio) with high-pitch in content and poor in technique reliefs - can not be compared with the best works of the Pisa school. Balduccio himself surpassed, apparently, while performing the tomb of Azzo Visconti, from which almost nothing is left except the figure of the duke, resting on his deathbed, in the collection of Trivoulcha in Milan.

One of the most important monuments of Lombard plastics of the second half of the 14th century is the tomb of St. Augustine (Arca di S. Agostino), now at the whim of fate standing in the cathedral of Pavia. Executed between 1362 and 1380, it was to overshadow the tomb of Peter the Martyr in Milan with wealth and pomp. The sarcophagus with the figure of Blessed Augustine lying on it, presented with the features of a life not yet extinct, stands under a marble shadow, opening on three sides in semicircular arcades. Her unusually figure-rich decoration is an instructive model for the history of the development of art. In the lower part there are still visible traces of the Pizan style of Giovanni di Balduccio, in the upper parts, together with a different sense of form and other equipment that neglects the drill, you can recognize the local, northern Italian style, with a more refined expression and personality of the heads, more slender and leaner figures. This is the style of Compionesi, sculptors from the city of Campione on Lake Lugano, who made up, apparently, an artistic fraternity, as before “Maestranza comaciana”.

The works of Campionesi, which belong to them reliably, are in Milan, Monza, Bergamo and Verona. Their participation in the creation of jewelry and sculptural decoration of the Milan Cathedral is attested by numerous documents. Let's call some names. Matteo da Campione (died in 1396) - the master of the excellent, graceful cathedral facade of the city of Monza, with a poor, but strict in style, sculptural decoration; he also owns the Imperial pulpit, which now serves as a rostrum for the choristers, - over the sculptures of the niches the statue of the Savior towers in the unusual image of a thunder-bearer.

In 1340, eight baptismal reliefs were made in Bergamo Giovanni da Campione with images from the life of the Savior, distinguished by subtle observation of nature; later, in a more monumental genus, he executed some sculptures of the northern portal of Santa Maria Maggiore - for example, a skillfully crafted equestrian statue of Sts. Alexandra.

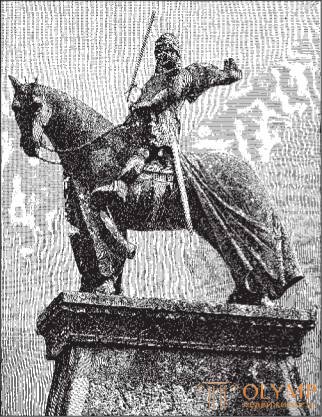

Fig. 309. Monument Kangrande della Scala in Verona. By meyer

However, the main works of Campionesi were the famous monuments of Scaliger (feudal race della Scala) in Verona. As unique works of Gothic small architecture and as monuments to the Veronese tyrants, standing in the open in a quiet, secluded part of the city, they make a special impression. In the history of Upper-Italian plasticity of the 14th century, they have an honorable place. The oldest and most impressive in their arrogance and simplicity is the monument of Kangrande della Scala (1311–1329), leaning against the wall of the old chapel of Santa Maria Antica. On a modest, devoid of decorations, a stone sarcophagus, supported by dogs, rests the figure of the deceased hero; above, in a sculpture set on the platform of a truncated pyramid, rising above the gothic canopy of the sarcophagus, he is depicted on his battle horse, covered with a large tournament blanket, with a drawn sword in his hand (Fig. 309). The author of this work is unknown. Из других памятников Скалигерам отметим монумент Мастино II (1353), также увенчанный конной статуей, и самый богатый и пышный памятник Кансильорио делла Гранде (1374), выполненный Бонинода Кампионе. Подле шестиугольного роскошного готического балдахина, возвышающегося над саркофагом с лежащей на нем фигурой умершего, поднимаются еще шесть особых угловых балдахинов, под которыми помещены статуи. Из конечностей их фронтонов и фиалов вырастает постамент с конной статуей. В целом памятники Скалигерам, выдержанные в пропорциях итальянской готики, говорят о спокойном и уверенном в себе мастерстве художников.

Тем, чем Кампионези были для Милана, Бергамо, Монца и Вероны, для венецианской области, как указал Бискаро, были Буони, Санти, мастера гробниц фамилии Каррара в церкви августинцев (Эремитани) в Падуе и братья Массенье.

В произведениях, возникших в это время в Венецианской области, чувствуется, что и здесь возбудителем нового направления явился пизанский стиль. Посредником в этом отношении между Пизой и севером можно считать Джованни Пизано, работавшего если не в Венеции, что не доказано, то, по крайней мере в Падуе для церкви Санта-Мария делль Арена (см. рис. 295). В городе св. Марка византийские художественные воззрения пустили более глубокие корни, чем в Средней Италии и Ломбардии, и лишь постепенно скульптуры, которыми продолжала украшаться церковь св. Марка, становятся романскими и готическими, не утрачивая, однако, под влиянием свойственного тосканской пластике драматизма своего внутреннего равновесия и внешнего спокойствия.

Лишь в два последних десятилетия XIV столетия законченный, мягкий стиль венецианской школы находит свое выражение в произведениях братьев Якобелло и Пьер Паоло делле Массенье. Их первая работа — большой мраморный алтарь 1388 г. в церкви Сан-Франческо в Болонье. Красивее группы небесного Коронования Богородицы, венчающего алтарь, это время не произвело ничего.

Brothers Masseni executed in 1394 statues of the apostles, Mary and St.. Mark on the altar barrier of the church of sv. Mark in Venice, full of dignity, free and complete figures; They are similar in style to the statues on the barriers of the two side aisles. Around 1399, both brothers were still working in the Milan Cathedral. The idea of Pierre Paolo is the great rich Gothic southern window of the Doge's Palace in Venice, which arose shortly after 1400. Giacomo Piero’s son was executed, for example, after 1386 the tomb of Jacopo Cavalli in the church of San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. In general, this gentle Gothic style forms in Venice a transition to the plastic of the 15th century and continues to live even in the Venetian early Renaissance.

Painting

The influence of Tuscan painting is felt in Northern Italy. True, the figures of the heroes written by Giotto in the hall for the festivities of the Palazzo Azzo Visconti in Milan have not survived, but his stay in Ravenna left traces visible to this day, and the Padua church of Santa Maria del Arena shines with eternally young beauty as the main work of the great Florentine. It is not surprising, therefore, that Giotto created a school in Upper Italy, which, apart from Venice, and here in the XIV century, public buildings were decorated with frescoes of a more or less Jott direction. True, the Djotte style encountered here everywhere with local artistic development, pursuing the same goals as Tuscan painting. But in general, the Gothic school of painting in Upper Italy itself produced so little outstanding that we can only glance at its development ...

In Romagna, where the innate softness of manners sought to be tempered on Djotte patterns, the starting point of stylistic development was, as Brach proved, the city of Rimini. This development can be traced from the golden background in yellow (i.e., golden) clothes and the light blue cover of the Madonna by Giuliano da Rimini in the Cathedral of Urbania to the New Testament frescoes of 1407 in Sant'Antonio Abate church. in Ferrara. For the time between these two dates, there are frescoes on the plots of the Old and New Testaments in the Church of Our Lady in Pomposa and in the small church in Mezzetrate, near Bologna. These murals can be partly compared with the easel paintings of masters of the Bologna school: Jacopo degli Avanzi, Simone dei Crocifessi, Vitale di Bologna, Jacopo di Paolo and others.

A little more significant were contemporary painters of the city of Treviso, of whom we already know Tommaso de Mutin (da Modena), the author of the portraits of Dominicans in San Nicolo in Treviso, who worked in Karlstejn Castle in Prague, in Bohemia. More original, within the limits of the Byzantine manner, are Venetian artists: Paolo Veneziano, from whose works, besides some paintings with his signature in his hometown, we are especially interested in The Fall of Paganism (1351) in the Stuttgart Gallery; Lorenzo Veneziano, whose “Madonna” is located in the Louvre in Paris; Niccolò Cemetikolo, the best picture of which is “The Coronation of the Virgin” (1367), in the cathedral of Padua, is full of inner life, but in a completely different way from that of the Jott painting. In which the frozen Byzantine style mosaics continued to work in Venice show, for example, the mosaics of the baptismal chapel of the church of San Marco.

Exceptions that are worth staying longer can be found in Verona and Padua. In Verona, the first famous painter Turone, the image of the Most Holy Trinity (1360) of which, in the Verona Pinakothek, does not yet have a single Jottish feature, is followed by the great Alticiero da Tcevio. Only a fresco that has arisen after 1390 in the tomb of the Cavalli family in the church of Sant'Anastasia in Verona, depicting Frederico Cavalli and his family, who bends the knee before the Madonna, can be attributed to him with certainty. He mainly worked in Padua with Assistant Avanzo, who apparently has nothing to do with the aforementioned Bolonian Jacopo degli Avanzi. The history of art since the days of Ernst Förster has repeatedly and extensively dealt with Altiquiero's relationship to this Avanzo, who, as one might think, his student, and their joint activities in Padua. Schlosser and Schubring continued similar research. The question concerns mainly two large frescoes, which, despite the closeness of their style to the Giotto school, go on and embark on new, independent paths. The earlier of these paintings (1376–1377) decorates the chapel of San Felice in the church of Sts. Anthony, patron of Padua. She depicts on the wide back wall besides the Crucifixion a series of events from the life of the Apostle James the Elder. The nature of the faces here is sharper than that of Giotto, the action develops with great realism, individual groups are no longer evenly distributed along the monumental lines of composition. Buildings and landscapes are depicted more believably, and even in some places, the transfer of airspace by changing tones is noticeable. The second painting (1377–1379) is in the chapel of St. George near the church of Sant Antoni. Large murals represent the youth of the Savior, the Crucifixion, the heavenly coronation of the Virgin, as well as the life of St.. Catherine, George and Lucia. Jotte nobility of compositions is connected here even more clearly than in the first cycle of frescoes, with new artistic truth: the size of the figures changes more correctly depending on their perspective removal, the nude body is more carefully modeled by light and shade, and a significant increase in colors makes it possible to achieve previously unknown hues. Concerning the belonging of the named frescos of Altiquiero and Avanzo or their comrades, opinions differ. For a series of paintings in the chapel of San Felice, the authorship of Altiquiero can be documented; pictures from the life of sv. Lucia signed name Avanzo. The main work of Altiquiero is rightly considered the great Crucifix in the chapel of San Felice. They, undoubtedly, also wrote a number of frescoes from the life of St.. George in the chapel of his name, while Avanzo except the cycle of St.. Lucia and some pictures from the life of St.. George belongs probably also to the “Battle of Clavigo” in the chapel of San Felice.

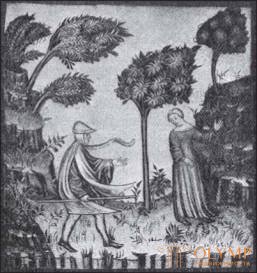

Fig. 310. The action of the north wind. Miniature from the book of the Cherruti family. According to Schlosseur

In Padua, Guarento is mentioned as a disciple of Giotto, whose work falls on 1338–1378. His name is signed Crucifixion Bassansky Pinakothek. In Padua, the remains of the frescoes of his brush remained, guided by which Shubring considered it possible to consider his style as an intermediate link between the style of Giotto and Altiquiero and called the art of both Veronians Padua.

Very interesting is the North Italian miniature painting of the 14th century. A series of miniatures of the Book of Genesis in the Rovigo Museum show how, from the middle of this century, the transfer of the depth of background space has gradually improved. The miniatures of the book Verona's Natural History in Paintings, which belonged to the Cherruti family and now kept in the Vienna Museum of Art and History, show how exactly the artists of nature could already convey (Fig. 310). Like the frescoes of Altiquiero and Avanzo in Padua, which perhaps also influenced the style of the frescoes by Antonio Veneziano in Camposanto in Pisa, these miniatures make it possible to feel the important role that Northern Italian painting was destined to play.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)