Introduction Architecture

As far as the notions of “medieval” and “renaissance” are arbitrary, it is revealed with particular clarity in the history of Italian art. As in the countries north of the Alps, in which the struggle between original origins and perceived forms is still not over, there can be no “rebirth” at all in this era, so it seems to us to be wrong for Italy - despite the awakened here in the 14th century, interest in the study of classical antiquity was to begin, together with some scholars, the history of the “renaissance” from 1300 or even from 1250. Even with Dante's “Vita nuova” nothing is being revived, but a new life of feeling, which has grown on the soil of the Middle Ages, is just beginning. In the Italian architecture around 1250, a complete break with ancient remnants was revealed, which lasted until about 1400. And the Gothic style entered Italy, as Anlar’s research established, came from France, but it didn’t appear here at first not quite in that form, and for most Italian architects generally remained unfamiliar advanced system of high Gothic. Dressing their buildings in gothic outfit, they otherwise sought to develop the building body according to their own artistic design. In addition to the lancet arches, the northern Gothic style is reminiscent only of those often used, such as schemes, phials, crabbs, and flares. Capitals, more relevant to the pillars, are rarely decorated with natural foliage, but retain the “buds” of the transitional style, and even more often - the ancient, deciduous patterns derived from acanthus. Windows with flat-cut bindings still so little tend to occupy wall spaces, as in the northern Gothic style, that the upper openings of the middle naves often come down to small round windows. The system of buttresses of the Gothic churches of Italy with the loss of the expansion arches, which are found only as an exception, loses all its character. Nevertheless, the arches of the same height are spreading more boldly, with wider spans, and the rooms of the same area overlap with arches with fewer supports than in the northern Gothic architecture. True, instead of buttresses, they appear then, least of all contributing to artistic impression, iron links and wooden beams, which (like the memory of open roofing rafters) connect the columns under the arches. Organic gothic in Italy already occupies, according to Burkgard, the not-so-often-used “spatial style” (Raumstil), in which greater importance is attached to the development of relations among themselves of free spaces as one of the main tasks of architecture than consistency and completeness. In the appearance of the building, this sequence of construction disappears completely. The towers not only do not grow organically from the western facade, as in the north, but are, like the ancient Italian bell towers, independent structures erected near the churches. The western façade remains, as it were, the ostentatious part without any connection with the body itself, literally the ostentatious side of it, since it is usually decorated with white and colored marble. Thus, Italian Gothic should be measured by its own scale: viewed independently of its individual forms, borrowed from northern architecture, in its best monuments it seems almost a special style that serves as an intermediary link in the transition from the Romanesque to the Renaissance.

The centers in which the flames of a new Italian art burned are in Tuscany and neighboring Umbria. True, the Gothic architecture, namely the Burgundian early Gothic of the Cistercian Order, penetrated into Lower Italy earlier than into Tuscany. The oldest Gothic church in Italy - the church of the Cistercian Abbey of Fossanuova between Piperno and Terracina - was consecrated as early as 1258.

Built by French craftsmen, it closely adjoins the Abbey church in Pontinha, Burgundy. In Central Italy, this architectural trend is represented by the church of the Abbey of San Galgano (near Montichiano), which was founded in 1218, in the Tuscan Maremmas [10]. The influence of the decorative forms of this church can be traced to the Gothic churches of Tuscany, at least to Siena. Soon the legacy of the Cistercians passed to the Franciscans and Dominicans: the spread of the Gothic style in Italy was their work. It was these churches of mendicant orders, intended for preaching, that first of all should have been spacious; they were the first to apply Gothic forms to the service of the Italian "spatial style" (Raumstil). The mother of the Italian Gothic is the church of San Francesco (St. Francis) in Assisi (1228-1253). Terraced soil surface caused the device of the Lower and Upper churches. According to their original plan, both of these churches are single-nave, with a single-nave transept and a simple apse. Heavy, Lower Church still gives the impression of Romanesque construction, while high, in noble proportions, the Upper Church already represents some forms of northern Gothic. Outside the round, tower-shaped buttresses resemble South French prototypes. But the smooth facade with a triangular false pediment and a “rose” above the pointed double arch portal is quite Italian. Vasari's assumption that this church was built by a German architect has been refuted by Tode. The pride of national Italian art is its wall and ceiling frescoes.

One of the founders of the Proto-Renaissance was the sculptor Niccolò Pisano (about 1220 - between 1278 and 1284), whom Vasari incorrectly called the builder of many churches. His students are architects Arnolfo di Cambio (died in 1301 or 1302), Giovanni Pisano (died after 1314), Niccolò’s son, Andrea Pisano (yes Pontedera) with sons Tommaso and Nino. The great painters of this era were Giotto (1266 or 1267–1337), Orkanya (first mentioned in 1343 or 1344–1368), Agnolo Gaddi (died in 1396).

Drawing first of all attention to the churches of the mendicant orders, we will see that, along with the Franciscan and Dominican churches with full vaulted coverage, some of the later and most mature buildings of this genus are in complete contradiction with the very essence of the Gothic style and retain the flat ceiling of the giant hall.

The transept, along with the longitudinal hull, has the ancient T shape, and on both sides there is very little prominent, straight or polygonal apse extending along the eastern wall of the transept, a series of quadrilateral chapels.

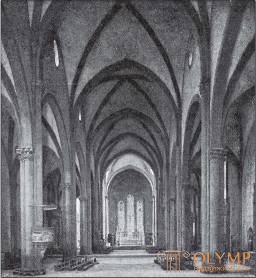

Fig. 287. The interior of the church of Santa Maria Novella. With photos Alinari

The oldest Gothic church in Florence is the Church of the Holy Trinity (Santa Trinita), built around 1250 and mistakenly attributed to Vasari Niccolò Pisano. Even now you can recognize its Cistercian origin. Ahead of the longitudinal hull with its five naves is a wide transept, barely protruding outward; naves, which were originally not blocked by chapels, consistently become lower and narrower. Behind the transept, against each nave, lies the straight-cut quadrangular choir. The cross vaults are supported by slender tetrahedral pillars. From the interior of the church there is an impression of lightness and nobility. The main Dominican building of Florence is the Santa Maria Novella (1278 - approx. 1360; fig. 287), a beautiful three-nave basilica completely covered with cross vaults, which Michelangelo called his bride. Its builders were Dominican monks, brother Sisto and brother Ristoro. Chapel choir cut straight and straight. Elegantly dissected columns consist of wide semi-columns attached to a four-sided rod, the corners of which are cut off. Only the lower parts of the rich, lined with white and black marble facade belong to this era. The most remarkable of the Franciscan buildings in Florence is the strict and majestic Church of the Holy Cross (Santa Croce), built since 1294 according to the plans of Arnolfodi Cambio. None of its interior spaces, with the exception of the polygonal (half octagon in plan) middle choir chapel, on the sides of which ten smaller rectangular chapels are arranged in a row, does not have a vaulted cover. Thus, not constrained by any constructive necessity, here could receive its full expression "spatial style". The weight of the tops is carried by simple, imposing severe force, octagonal pillars. The ratio of the parts on which all the art of architecture is based, here gave wonderful results.

In Siena, the churches of San Francesco and San Domenico belong to those single-nave buildings with open rafters, which were called “giant barns”. In Pisa, the same class of unassuming churches for preaching includes, in spite of its vaulted choir, the church of San Francesco (now a museum); but this same city has two small Gothic churches, Santa Caterina and Santa Maria della Spipa, with their magnificence reminiscent of Italian marble cathedrals of that era.

It is clear why the Gothic cathedrals of Italy are at a higher artistic level than the earlier churches of mendicant orders. In most cases, the builders of these cathedrals were rich cities, whose citizens imitated feudal lords, and the rivalry of the neighboring urban communities provoked the noble competition in the field of art, which contributes to the creation of the greatest works. The earliest of them is the Siena Cathedral, in which the magnificent façade, lined with dark, white and red marble and completely covered with sculptures, primarily composed by Giovanni Pisano (1284), primarily attracts attention. An attempt to refute the authorship of Giovanni failed. At the top, this facade is somewhat incongruously crowned with three gables in the number of portals; of these, the average is significantly higher than the rest. The same gables rise above the semicircular arches of the portals. On the sides, the facade is furnished with two corner pillars with pointed arches pierced into them. The interior of the cathedral, without communication with the side parts of the facade, is a three-nave basilica, whose chorus seems to be a continuation of the front of the building on the other side of the multi-nave transept. The wrong hexagonal dome over the middle part of the temple, in which the influence of the Pizan dome is noticeable, was only later somehow brought into contact with the plan of the cathedral. The fact that the construction of the Siena Cathedral since 1259 was led by the monks of the Abbey of San Galgano best explains the borrowing of some of the Burgundian early-Gothic forms. The variegated inlay of the walls in rows of white and dark marble was, of course, taken from Pisa (see Fig. 139). At the same time, over the four-sided pillars with half-columns, there are still semicircular arches, and only the walls of the side aisles have real Gothic windows.

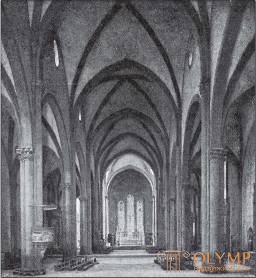

Fig. 288. Facade of Orviet Cathedral

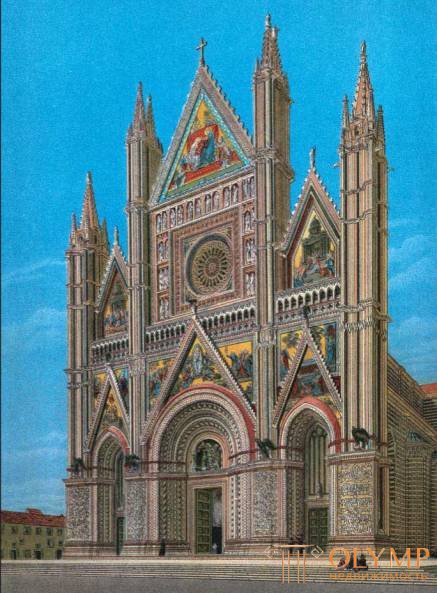

Fig. 289. Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore with the bell tower (left) in Florence. With photos Alinari

With the interior of this magnificent church of Siena, there is no resemblance to the interior of the cathedral in Orvieto, which resembles an ancient Christian basilica with open rafters. The cathedral was begun by construction even before 1285, but the charming facade of Orviet (fig. 288) is undoubtedly the younger brother of Siena. Its construction from 1310 led by Lorenzo Maitani from Siena, as Fumi proved. Its three main gables also correspond to three gables of portals. But unlike the Siena Cathedral, only the middle portal has a circular arch; Above the side doors are slender lancet windows with simple carving of columns and bindings. The unusually rich sculptural decoration of the Siena facade in Orvieto is replaced by flat fields covered with painting. The images on the lower main pillars, however, are embossed; gable imprints and wall surfaces are decorated with mosaics on brilliant gold backgrounds, though only partly from the fourteenth century.

The main work of Giovanni Pisano is the magnificent cemetery of Camposanto (1278–1283). This is a huge gallery located on a rectangle, covered with rafters, a sort of cloister's gallery, surrounding the courtyard, to which it opens with six spans with round arches and 56 large windows of the same kind, separated from one another by pillars; the upper part of these windows is framed by exquisite gothic carvings. A strong artistic impression is achieved here with majestic proportions.

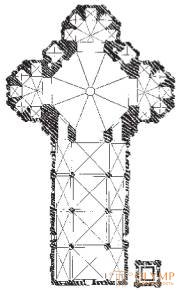

Fig. 290. Plan of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Lubka

Arnolfo di Cambio, following his Franciscan church in Florence, embarked on the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, designed to eclipse all the churches of Italy (Fig. 289). The building was entrusted to him in 1296, but it was completed only long after his death, and, moreover, with many deviations from the original plan. In the construction of this cathedral took part, one might say, the entire population of Florence and all its artistic forces. From 1334 to 1336 the building was led by the great painter Giotto di Bondone; He also owns the first project of the famous bell tower (Fig. 290 and 289). Between 1357 and 1366 there was a longitudinal body in its modern form. Its main builder was Francesco Talenti. In 1367 a large commission of artists and noble citizens finally worked out a plan for the eastern, central-domed part of the building, the construction of which lasted until the second half of the 15th century. The construction of the dome by Filippo Brunnelski (1420-1434) is even considered one of the first great works of the early Renaissance in the field of architecture. If the Florence Cathedral still counts among the wonders of the world, then it owes it above all to its bell tower and dome, the monumental and clean lines of which far dominate the valley of the yellow Arno. The interior leaves a rather vague impression. The huge three-nave longitudinal case is covered with lancet-arched vaults; the high middle nave consists of four unusually wide spans; in the eastern part, the transept and the choir are replaced by a three-winged structure of the central type, covered with an octahedral dome. Despite its gallery (see Fig. 306), often blamed for the fact that it, relying on the cantilevers, is stretched along the heels of the arches, without an organic connection with them, the longitudinal body impresses with its simplicity and powerful grandeur. Its tetrahedral pillars with broad leafy capitals served as models for the pillars of many Italian Gothic churches in the manner of their dismemberment and turned out to be strong enough to support the huge arches rising above them. The dome room suffers from darkness most of all because only four of its eight sides are open, while the rest, communicating with the side rooms with low aisles, rise to the dome with almost solid, impenetrable masses.

The Florentine taste for noble proportions, elegant marble inlays and fine sculptural details were shown one after another in the famous bell tower of the cathedral - Giotto, Andrea Pisano and Francesco Talenti, in which it was finished in 1358. The upper floors are not narrowed, but facilitated by the gradual expansion of window openings. The pointed spire, apparently part of Giotto’s plan, was not fulfilled, but it’s just the horizontal ending that makes this tower so characteristic of Italian Gothic.

Less interesting are the rest of the cathedrals of Tuscany and Central Italy. The restructuring of the Prato Cathedral (1317) was also led by Giovanni Pisano. In the cathedral of the city of Lucca with its Gothic pillars, as in Santa Maria del Fiore, everywhere under the gothic envelope is visible the core of the old Romanesque structure. Perugia Cathedral - the only Italian church of this era with three aisles of equal height (the hall church) - recalls the northern origin of the Gothic.

In the Tuscan cities, whose communities, with all their piety, lived with secular interests and tastes, along with the temples, magnificent public buildings were also preserved. In the field of Gothic applied architecture, beautiful fountains of city squares competed with chairs, altars and tombs inside churches.

In Florence, Arnolfo di Cambio finished (1299–1301) the front of the Signoria Palace (Palazzo Vecchio, or Palazzo della Signoria). Its three-story walls rise proudly with double Gothic windows framed by semicircular arches; the fourth floor, which protrudes forward on consoles, is crowned with battlements and is equipped with loopholes; towering above it, a slender four-sided watchtower, which also served as a bell tower, forms together with the building's body a somewhat fragile, but majestic whole. Similar to the Palazzo Vecchio outside the old courthouse (now the National Museum), the Palazzo del Podesta, or Bargello, whose courtyard, built between 1333–1345, with its monumental gallery on the pillars and an open, extremely stylish staircase, is especially remarkable.

The famous rectangular Orsanmichele building, started in 1337 and originally served as a bread shop, in 1366–1404. It was converted into a church with graceful pointed windows. The impression of the Gothic building, however, is no longer made by the elegant courtyard of the corner house Bigalo, which once belonged to the brotherhood of care for the foundlings, with its wealth of decorations and round arches. The complete transition to the subsequent epoch represents Loggia dei Lanzi - a portico open to the square for public celebrations, built successively by the father of Orcania, Bencha di Chone, by Orcanja himself and Simone Talenti. It opens on the Piazza della Signoria (Piazza della Signoria) with three wide semicircular arches. The general view of the loggia is just less Gothic, but the pillars are the same classical pillars of the Italian Gothic, which first appear in the Florence Cathedral.To the Gothic features of this monumental building also belong to the double shamrocks in the corners between the arches and supported by the balustrade consoles, ending at the top of this monumental building.

Florentine dwelling houses of this era, built mostly of coarse stone blocks (rustica) and more like a fortress, are very interesting for the history of this kind of architecture, as noted by Jacob Burckhard. Blocks often remained unprocessed, primarily because of a lack of funds and time; usually only their edges were hemmed at the seams. The resulting appearance of the wall was improved later, when the rustic, rough and rough, masonry began to be located on different floors. The simple, even, often octagonal pillars of the courtyards are still connected by means of semicircular arches, while the windows are dominated by the pointed arch and often the coronal eaves, or even the whole upper floor (attic) protrudes from the wall surface, resting on the arched arch consoles. Typical examples of the buildings of this kind are Spini, Castellani, Davance Quarratesi palaces. The courtyard of the Palazzo of Count Bardi with round columns, equipped with palm leaf capitals and standing on attic bases, has already the character of a Renaissance building. Even better than in Florence, preserved a number of medieval palaces in Siena. The brick Palazzo Publiko (Town Hall, 1288-1309), repeating the basic forms of the Florentine Palazzo Vecchio, is more spacious, more fun and taller than the latter. The more elegant Florentine houses-fortresses brick palace Palazzo Buonsinori. Its two upper floors have seven triple pointed windows and end with a toothed crown, lying on a powerful ledge of the frieze, which consists of a series of pointed arches. From the picturesque gothic fountains of Siena, the Fonte Brand stands out, overshadowed by a three-sided loggia and belonging to the 13th century. In Perugia - high on the mountain located in the charming capital of Umbria, the town hall (started in 1281) is a smooth stone building with beautifully framed windows and a classic semicircular portal (1340). Antique ornaments mixed with individual features of Gothic ornamentation. Especially beautiful is the fountain Fonte Maggiore (1281), made according to the drawing by Niccolò Pisano and consisting of three bodies of water, one above the other. Pistoia, Lucca, Orvieto and Viterbo are also famous for their luxurious palazzo. Carefully preserved the medieval style of its buildings a small mountain town of San Gimignano (halfway between Florence and Siena). From its quiet narrow streets, from the 13 slender Gothic towers towering above the city, it blows upon us in a far-off, artistically-inspired time.

Plastics

The mid-thirteenth century for the visual arts of Italy, especially in Tuscany, was a time of rapid artistic progress. Plastic before painting took advantage of new opportunities. Here an innovator was Niccolò Pisano (about 1220 - between 1278 and 1284). His followers are Giovanni Pisano (died after 1314); Andrea Pisano (Andrea da Pontedera; about 1290–1348 or 1349) and his sons Tommaso and Nino.

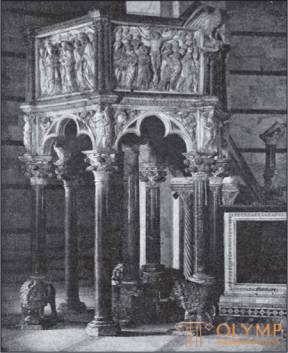

Fig. 291. Niccolò Pisano. Marble pulpit. With photos of Brodgy

Niccolò Pisano’s father was originally from Puglia, but he himself, as the inscription found by Polachek on his fountain in Perugia proves, was a pisan, and if we compare his style with the style of such earlier Tuscan works, such as the sculptures of St. Martina in nearby Lucca, then everything will become clear. At first glance, the art of Niccolò Pisano seems to be a return to antiqua, because the figures of his early works he borrowed mostly from late antique sarcophagi in his hometown, and the traces of Byzantine art seen in his works are explained by the works of his Tuscan ancestors. It is important that Niccolò became the first spokesman for a new view of nature in plastic. Crowe, Cavalcazelle, Schnaze, Hans Semper, Dobbert and Bode shared the correct opinion of the local origin of art by Niccolò Pisano. On the contrary, Venturi and Berto in Italy, P. Schubring and O. Wolf, in Germany, spoke of Lower Italian or even Byzantine origin of his style; on the other hand, Marcel Ramone and Hyacinth tried to bring him out of the French high Gothic. Ludwig Justi and Andreas Möller defended our view, which corresponds to the true meaning of the great sculptor. It must be remembered that in the plastic of the whole of Europe in the middle of the 13th century, a trend towards ancient art is found, which can be observed in Tuscany, in Lower Italy, and in Vekselburg, Bamberg, and in Reims, and then this controversial issue will lose its urgency. At the late antique sarcophagi, Niccolò Pisano studied the development of his remarkable high relief, the main figures of which appear almost like in a round plastic; from them, he borrowed a thorough polishing of the naked body, often pompous piles of clothes, work with a drill. However, it is important that Niccolò was able to recognize through the veil of oblivion the inner greatness of the ancient figures of the gods and transfer it to his Christian sacred images, which even without haloes give the impression of heralds of the extraterrestrial world. Niccolò’s earliest authentic work is a hexagonal marble pulpit in the Pisa baptismal (Fig. 291), completed in 1260. The entire structure rests on a single middle column and six corner pieces, three of which rest on the backs of marble lions. The gothic features of this department include the kidney capitals of the corner columns, the three-leaved arches connecting them, as well as the bunches of columns of red marble, which separate the balustrade reliefs from one another. On the contrary, six angular allegorical figures of the balustrade have an antique character - and not only Hercules, as the ancient personification of the Force (see fig. 294), a naked classical figure, but also female dressed, such as Vera sitting on a throne, a figure that is relief with the Crucifix is explained as "Fides". The main sculptures of the pulpit of the Pisa baptismal are large reliefs of the five sides of the balustrade; the sixth side is occupied by a staircase. In the first field, the compositions “The Annunciation” and “The Nativity of Christ” are skillfully combined into one whole, where the twice repeated matronal figure of the Mother of God is singled out in the form of Juno. The reliefs “The Adoration of the Magi” and “The Meeting in the Temple” are magnificent. In The Crucifixion, the shape of Christ’s body is as powerful as if Niccolò Pisano was Michelangelo’s immediate predecessor. Placed in the fifth field, “The Last Judgment”, with its restless general performance, reveals a new artistic feeling, noticeable in the details of the other four images. Later, the reliefs of this department are made the most mature of the sculptures of the portal of the Cathedral of St.. Martina in Lucca - the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi and - in the timpane - The removal from the cross, which we consider only to be the work of the school of Niccolò Pisano. A more balanced composition of subjects in comparison with the Pisa chair differs reliefs completed in 1267 with images from the life of St.. Dominica on his marble sarcophagus (Arca di San Domenico) in the church of this saint in Bologna. We know that here Niccolò’s assistant was his apprentice Fra Guglielmo del'Anello from Pisa, and, apparently, he was given the master a major part in the implementation of reliefs.

With many assistants, of whom we already know Arnolfo di Cambio, Niccolò created between 1266 and 1268. its second significant work was the pulpit of the Siena Cathedral, which received instead of a hexagonal octagonal shape and therefore was decorated not with five, but with seven relief images on evangelical themes (Fig. 292). The beating of babies in Bethlehem is here, and two fields are dedicated to the Last Judgment instead of one. It is instructive to see that Niccolò himself has become a different artist here, more relevant to his time. The figures are natural, their heads are more expressive, the movements are more alive than in similar images of the Pisa chair; but it is precisely because of this that they lose their characteristic classical-Roman majesty, which distinguishes the figures of the Pisan reliefs. Here, more than in Pisa, participation in the work of students is noticeable; nevertheless, these reliefs are obliged, undoubtedly, to the master himself, and not to his son Giovanni, whom he first received permission to introduce to work as a novice sculptor.

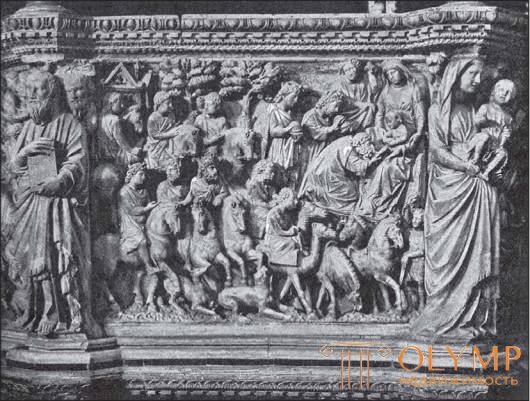

Fig. 292. Adoration of the Magi. The relief of the department of Niccolò Pisano in the Siena Cathedral. With photos Alinari

Giovanni Pisano and Arnolfo di Cambio took part in the performance of Niccolò’s last work, the “Big Fountain” in Perugia (1277–1280). The lower, 24-sided large reservoir is decorated with 48 reliefs embodying all the knowledge of that era. Around the upper part, 24 statuettes representing the persons of the Old and New Testaments stand on cantilevers under canopies. The most beautiful and lively belong, of course, Giovanni Pisano. Disagreeing with other researchers, we believe that the development of Giovanni did not go in the opposite direction with his father’s activities, but, on the contrary, under his personal supervision.

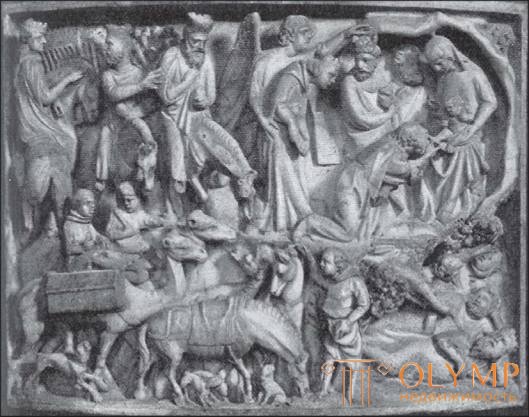

Fig. 293. Adoration of the Magi. Relief of the Department of Giovanni Pisano in the Cathedral of Pisa. With photos of Brodgy

Arnolfo di Cambio (1232–1301 or 1302) was a more significant architect than a sculptor. His sculptural works include, for example, the tomb of Cardinal de Brae in the church of San Domenico in Orvieto - a prototype of numerous later monuments depicting the deceased on his death bed, before which angels or boys kliroshane retract the veil (fancinlli del coro), while how above the saints bring the same dead person to the Mother of God. Fra Guglielmo del'Agnello from Pisa (about 1228 - after 1313), about 1270, carved the quadrilateral chair of the church of San Giovanni-outside-city in Pistoia. Her 10 reliefs, in addition to scenes from the earthly life of the Savior, are reproduced and scenes from the life of Our Lady.

Fig. 294. Niccolò Pisano. Strength. The statue at the pulpit in Pisa. From a photo of Shubring

Giovanni Pisano (approx. 1250 - after 1314), brought up not in the Pisan, but in the Siena department of his father, was one of the first to consciously break with the ancient tradition in order to take the path of direct study of nature. Instead of short, squat figures of the Pisa Niccolo department, thin, wiry figures of men and women appear. Instead of classical calm, a lively, passionate spiritual expression appears in faces and gestures. Strong in its simplicity, the story gives way to dramatic animation. The reliefs of Giovanni are even more full of figures than the reliefs of his father, but they are more skillfully placed on the plane. Supino, Max Sauerland and Ludwig Yusti were engaged in the study of the works of Giovanni Pisano, although their conclusions somewhat differ from each other. In the fountain of Perugia, Giovanni apparently belongs to the reliefs of the "free arts" and is a graceful in its movement, a widely and freely draped sit-down figure of Rome. On the magnificent facade of the Cathedral of Siena, which Justie attributed to Giovanni, are colossal statues of prophets and sibyls (circa 1290). These works, fundamentally completely new in their design, belong to the most powerful creatures of the Middle Ages. His pulpit at Sant-Andrea in Pistoia (finished in 1301) resembles the Pisa pulpit of Niccolo in appearance; but its angular figures, like the reliefs of the balustrade, reveal a transition from measured to more free movement, from stylishly wide draperies to more natural, with small folds. In full brilliance, the new style is represented by the department of the Cathedral of Pisa (1303–1311, fig. 293); it was later broken, but pieces of it were placed in the Public Museum in Pisa. To give yourself an account of the differences between Niccolò and Giovanni Pisano’s style, it’s enough to compare, as Schubring does, the “Power” of Niccolò with the “Power” of the Pisa department of Giovanni (Fig. 294 and 295). The figures of the Sibylles, of which two are in the Berlin Museum, seem almost like the ancestors of similar figures by Michelangelo.

Madonna Giovanni, whose types with their oval heads and narrow eyes created a school, is no less interesting if viewed in chronological order: the marble Madonna of Prato Cathedral, (approx. 1275); Madonna of the Berlin Museum. The Gothic bend, to which Giovanni paid tribute to the spirit of the time, appears in the Madonnas on the portals of Camposanto and the Baptistery in Pisa, and the S-shaped posture reaches its extreme expression in a figurine from a bone bone of 1299 (not 1310) stored in the sacristy Pisa Cathedral. The most pure in form is the statue of Our Lady in the church of Santa Maria del Arena in Padua.

Fig. 295. Giovanni Pisano. Strength. The statue, the remainder of the Department of the Cathedral of Pisa. From a photo of Shubring

The sculptural style of Giovanni Pisano with his mode of transmission of action, directly inspired by life, had an impact on all Tuscan art of the XIV and even XV centuries.

The great painter Giotto (1266 or 1267–1337) not only composed the project of the Florentine campanile (bell tower), but also composed compositions of both lower rows of biblical and allegorical relief images placed in polygonal or rhombic fields. They were executed, however, for the most part by Andrea Pisano, who continued to work after Giotto's death: in the bottom row, for example, the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve, the invention of tillage and spinning art, pastoral life, music, blacksmithing, winemaking, etc. ; in the top row on the west side are seven major virtues, on the south — seven works of mercy, on the east — seven pleasures, on the north — seven sacraments. The history of the development of the customs of the human race and its economic activity is presented here in pure reliefs in form and style with the help of a small number of very expressive figures. Andrea Pisano (about 1290–1348 or 1349) is an outstanding master. He transferred the plastic of the Pisans to Florence, where in 1330 he created his main work - magnificent bronze doors that now adorn the southern entrance of the baptismal. Of the 28 fields framed in gothic taste, the four lower ones are decorated with allegories of virtues sitting on thrones, and the rest contain scenes from the life of John the Baptist (fig. 296). Andrea Pisano overcame the difficulties of Giovanni’s overly complex pictorial relief style. Its relief is cleaner and not so high. With the help of a few figures with the correct proportions, the subjects are unusually clearly conveyed but simply and expressively connected to each other against the background of the background. The perfect style of the XIV century. reigns in these works in the noble enlightened beauty. The sons of Andrea, Tommaso and Nino also left us some credible works. Madonna Nino in Santa Maria Novella in Florence and in Santa Maria della Spipa in Pisa denote a peculiar further development, since in them the human manifests itself in national and household features.

The Gothic style gained its final expression in Florence in the works of the painter Andrea di Chone, called Orca (first mentioned in 1343 or 1344–1368). His main work is facing a large ciborium in Orsanmichele in Florence (1359). Inside the elegant Gothic decorations are numerous allegorical and biblical half-figures. Clear, but serious and even harsh figures represent the 12 apostles above, in the four corners of the arches; Eight scenes from the life of the Mother of God, placed on a socle, show that Orcania was able to combine, in relief, the pictorial and complex composition of Giovanni Pisano with the balanced calmness of Andrea Pisano. Backgrounds in these reliefs - solid, as in painting. Separate compositions are composed by means of dzhottovskih dignified figures, outwardly calm, but full of internal revival. It was hardly anything more attractive than the relief of the Nativity of the Mother of God (Fig. 297).

Fig. 296. Andrea Pisano. Two planks of bronze doors with the compositions “Judea before the prison of John the Baptist” and “The sermon of John the Baptist” in the Florentine baptistery. With photos Alinari

The large main relief of the back side depicts the Assumption below, the heavenly glory of the Virgin Mary at the top. Despite the multitude of figures, here too, there is calm, inspired by a deep feeling, and the look is not distracted from the whole to the particulars by too much naturalism of execution.

Fig. 297. Orkanya. Nativity of the Virgin Mary. Relief on the civoria of the Church of Orsanmichele in Florence. With photos of Brodgy

The end of the 14th century includes round medallions with allegories of virtues on Loggia dei Lanzi, made in 1383–1387. from drawings by Agnolo Gaddi, as well as sculptures with which Simone Talenti, the son of Francesco, decorated Orsanmichele. Small statues placed on internal and external window covers give the impression of graceful ornaments, whereas Madonna of 1299, in the left side nave, with the Baby still dressed in a little shirt, with its general, typical forms makes it possible to guess that even more energetic efforts were required. in the direction of living observation of nature than those that made the XIV century.

AT

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)