Day and night, light and shade. These opposites are fundamental in human life and in nature in general. For the artist, white and black are the most powerful means of expressing light and shadow. White and black are opposite in all respects, but between them there are areas of gray tones and the whole series of chromatic color. The problems of light and shade, white, black and gray, as well as the problems of light and shade of pure colors themselves, as well as their connections, must be carefully studied, because the solution of these problems turns out to be especially necessary in our creative work.

Black velvet is probably the blackest color, and barium sulfate is the whitest. There is only one maximally black and one maximally white color and an infinite number of light and dark shades of gray that can be turned into a continuous scale between white and black.

The number of visible shades of gray depends on the sensitivity of the eye and the limit of perception of the viewer. This limit can be reduced by practical exercises, and thus the number of gradual transitions distinguishable by the eye will be increased. A uniform gray color, its lifeless surface can gain mysterious activity with the help of the finest modulations of the shadow. This feature is of great importance for painters and designers, requiring them to be extremely sensitive to tonal differences.

Neutral gray is a characterless, indifferent achromatic color, easily changed by the effect of contrasting colors. He is mute, but easily excited and gives great shades. Any color can immediately bring gray from a neutral achromatic tone to the color range, giving it a shade that is complementary to the color that arouses it. This transformation takes place subjectively in our eyes, and not objectively in the color itself. Gray color is a barren, neutral color, the life and character of which is dependent on the colors adjacent to it. It softens their strength or makes them more intense. As a neutral mediator, he reconciles the bright opposites among themselves, at the same time absorbing their power and thereby, like a vampire, finding their own life. On this basis, Delacroix rejected the gray color as consuming the power of other colors.

Gray can be obtained by mixing black and white or yellow, red, blue and white, or any other pair of complementary colors.

First, we will build a consistent twelve-step series of gray tones, ranging from white to black. It is very important that the steps are lined up strictly to the same degree of dimming. The gray color of the middle tone should be located in the center of the scale, and each tier should be absolutely monochromatic and free from stains, and between the treads there should be neither a light nor a dark line. A similar scale can be made for any chromatic color. If we take the tonal range of blue, then blue is dimmed black to blue-black and lightened to white to blue-white.

These exercises are designed to develop sensitivity to color shades. Twelve tones in art is not that the system of "well-tempered clavier" in music. In the art of color, important expressive means can be not only certain intervals, but also imperceptible transitions, like a glissando in music.

The following exercises are intended to provide an in-depth understanding of the contrast between light and dark. So, choosing several gray tones from their common scale, it is necessary to create a single composition, connecting them together in any order.

After completing four or six such compositions and comparing them to each other, we find the most successful solution. Students quickly understand the meaning of well-built, convincing solutions and bad, unstable. This very simple exercise reveals the ability to master the art of contrast between light and dark.

Figure 11 shows the development of a composition of light and dark colors, arranged in a checkerboard pattern. This composition can be solved in lighter or darker tones. The task of the exercise is to cultivate the vision and sensation of the gradations of light and dark and their contrast.

Having mastered the problems of the tonal ratios of white, gray and black, one can proceed to the study of contrasts based on proportional and quantitative ratios of colors. The contrast of proportions is the opposition of big to small, long to short, wide to narrow, thick to thin. In order to master this, you need to perform exercises on the proportional ratios of light and dark, which develop not only a sense of proportions, but also a perception of positive — dark and negative — white, residual forms.

In European and East Asian art we find many works that are built exclusively on the pure contrast of light and dark. This contrast was of great importance in the ink painting of China and Japan. The basics of this art have grown from calligraphic writing. Font drawings had a huge wealth of forms. To achieve semantic and rhythmic accuracy of execution, the draftsman had to make a huge number of hand movements. The precondition for “correct” writing with a brush was also a sense of form, rhythmic flair, and intuitive plastic movements. “Just as an archer precisely marks a goal for himself, pulls the string and shoots an arrow, so the writer must concentrate, imagine the shape of the signs, and then with a strong confidence and firmly guide the brush.” So said the Chinese Chang Yie.

This manner of writing is the result of internal automatism. Just as font characters only after endless exercises, eventually, as it were, automatically flowed from the brush, so the study of nature forms in Chinese and Japanese artists continued until their reproduction was performed almost “by heart”. This automatism assumed spiritual concentration and at the same time easing physical tension. Meditative exercises in the vat or Zen Buddhism formed the basis of spiritual and physical training. Therefore, among the greatest artists working in the ink, we find many monks belonging to these sects. But the monks not only meditated to become artists, but also used brush painting as meditative exercises to achieve inner concentration.

The way of the image in woodcuts and copper engravings is also based on a comparison of dark and light. Due to the direction of the stroke and the tonal planes, the engraver can achieve a differentiated transfer of all gradations of dark and light. Using these methods, Rembrandt in his engravings sought solutions to a huge number of very different topics. And it is not surprising that in his drawings with a pen or brush, skillfully using chiaroscuro, he often achieved the strength of suggestive persuasiveness characteristic of East Asian ink painting.

Seu in his numerous drawings scientifically approached the construction of gradations of light and dark. Rationally considering point by point, he sought in his drawings, as well as in his paintings, the softest tonal transitions.

So far, we have studied the contrast of light and dark only in the area of black-and-white-gray tones. However, it is extremely important to learn to distinguish how much one color is lighter or darker than another. This ability can be developed through the following three exercises. On a sheet of paper, grafted like a chessboard, one of the cells is filled with yellow, red or blue paint. The task is to match each of these colors with equally bright or equally dark colors. It is necessary to ensure that in each exercise were used respectively yellowish, bluish or reddish colors. Also, do not confuse saturation or purity of color with its lightness. The task, the essence of which is to write all the colors as bright as yellow, is very difficult, because the fact that the yellow color is very light is not immediately known (Fig. 13). Another difficulty also arises when the yellow color should be shown as dark as red and blue. Light yellow color when dimming necessarily losing its character. Therefore, many artists have a natural desire not to obscure it. In Figure 14, all colors are given in the same darkness as the blue in the center.

Cold and warm colors are particularly difficult. Cold colors give the impression of transparency and lightness and in most cases are used too light, while warm colors, due to their opacity, are used too dark.

The same lightness or the same darkness makes colors as if related. Due to the same tonality they become as if connected and united with each other. This fact and its possibilities as an artistic tool cannot be underestimated.

The problems of light and dark in chromatic colors and in their relation to achromatic colors — black, white and gray — are particularly complex.

The color ball (Fig. 51, 52) presents both the chromatic colors of the color wheel, consisting of twelve parts, and achromatic. In contrast to the vibrant vibrations of a variety of chromatic colors, the achromatic gives the impression of rigidity, inaccessibility, and abstractness. However, with the help of chromatic colors in achromatic colors one can awaken the quivering vitality.

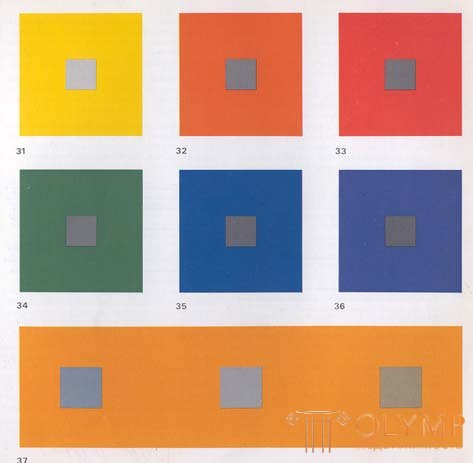

In figures 31-36, we see how the achromatic gray is so influenced by the neighboring color that it begins to seem additional to it. When chromatic and achromatic colors of one lightness are involved in and adjoin each other in the composition, the latter lose their neutral character. If the artist wants the achromatic colors to retain their character, he is forced to lighten or darken the chromatic colors. If white, gray and black colors are used in a color composition as a means of creating an abstract impression, then this composition should not have chromatic colors of the same lightness, because otherwise, as a result of simultaneous contrast, gray will give an impression of chromatic color. If in a color composition gray is used as a pictorial component, then it should be the same lightness as chromatic colors.

While the Impressionists sought a pictorial effect of gray tones, supporters of constructive and realistic painting treated black, white, and gray as a means of abstract exposure.

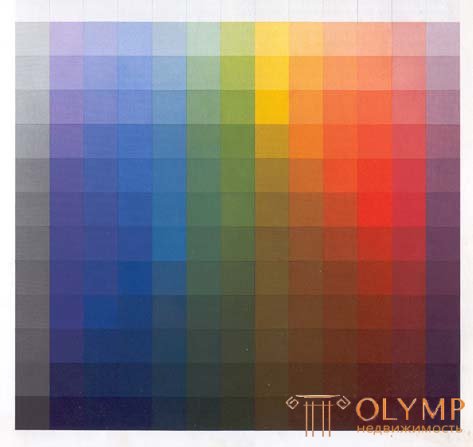

The problems of color contrasts of light and dark can easily be solved with the help of the exercise presented in Figure 15. To the twelve-part grayscale tones in its transitions from white to black, we add twelve pure colors of the color wheel, corresponding in their lightness to grayscale gray. And we see that pure yellow color corresponds to the third step of gray, orange - the fifth, red - the sixth, blue - the eighth, and purple - the tenth. The table shows that rich yellow is the brightest of the purest colors, and purple is the darkest. So the yellow color, to coincide with the dark tones of the gray scale, should be muted, starting from the fourth step. Pure red and blue are located more deeply, at a distance of only a few steps from black and far from white. Each admixture of black or white reduces their saturation.

If we prepare a table with a sequence of eighteen steps instead of twelve and combine the colors of maximum purity between us, we will see that the curve will have the shape of a parabola. The fact that saturated, pure colors differ in lightness, as shown in the table in Figure 15, is extremely important. We should learn that a pure, rich yellow color is very light and that there is no such substance as dark yellow color. Rich, especially blue color is very dark, and light blue - faded and weakened. Only a sufficiently dark red color can radiate its power, and clarified to the level of pure yellow loses it. A colorist must take this into account in his compositions. When the painter needs a rich yellow to create the maximum impression, the whole composition should be light in nature, while rich red or blue require a total dark solution to the composition. Glowing red in Rembrandt's paintings shines so expressively only because of the contrast with the darker colors. When Rembrandt wants to shine yellow, he immerses him in a relatively light color range. While the saturated red in this environment begins to give the impression of just something dark and loses its sonority.

Differences of colors in their lightness poses particularly difficult tasks for artists working with textiles. It is known that a textile project is solved at once in four or more coloristic variants, which in the collection must have a certain color unity. The basic rule here is for each color version of the picture to have the same system of contrasting ratios, as in Figures 11 and 12. If the main project has a pure red color, then the other color options will not have sufficiently pure colors that have the degree of lightness that red has. But the ratios between the tonal gradations in all variants should be the same. If the red color is replaced by orange, then the entire color composition must be rebuilt in accordance with the steps of the tonal gradation of this color. And in this case, the fabric with an orange pattern will be generally lighter than the fabric in the red version. If we wanted to equate the orange color to the degrees of the gradation of red, then a pure brown-orange color would correspond to a pure red.

The great difficulty lies in the fact that the relationship of lightness and darkness of pure colors changes depending on the intensity of illumination. Red, orange and yellow appear to be darker under insufficiently bright light, while green and blue under these conditions are perceived lighter. The colors and their relationships perfectly manifest themselves only in bright daylight, and at twilight they turn out to be distorted. Paintings written for the altar and designed for the semi-darkness of the church should not be displayed in a bright artificial light, because such lighting will distort all light color ratios.

I would like to emphasize that for a painter a rich yellow color does not contain either white or black, they are not present in pure orange, red, blue, violet and green. When a painter speaks of a whitened or blackened red color, he means his foul, unclean character. The technical meaning of blending with black and white has a different meaning.

The picture, written in the contrast of light and dark, can be sustained in two, three or four basic tonalities. The artist works, as they say, in two, three, four colors, while taking care that the main groups are well coordinated with each other. Each of the plans may have slight tonal differences, which should not erase the differences between the main groups. To comply with this rule, it is important to have an eye that perceives colors of equal lightness. If the main tonal groups or plans are not followed, the composition loses organization, clarity and strength.

The main reason that makes an artist work with plans is the need to keep her overall flatness in the picture. Thanks to the orderliness of the plans, all undesirable depths can be smoothed and secured. The development of the space inside can be stopped due to the correlation of all tonal relations with the tonality of the plans. Usually plans are divided into front, middle and rear. But it is not necessary that the main figures always be in the foreground. The foreground may be completely empty, and the main action will unfold on the middle ground.

The visual possibilities of the principle of the contrast of light and dark can be demonstrated by the examples of Francisco Zurbaran's painting (1598-1664) “Lemons, oranges and roses”, Florence, collection of A. Contini-Bonacossi; Rembrandt's paintings The Man with the Golden Helmet, Berlin, Art Gallery, and Pablo Picasso's Paintings The Guitar on the Fireplace, 1915.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)