The Novobrechman art is the hereditary successor to the Buddhist art of India, which it gradually began to supplant since the 8th century AD. e. Everything that he created with his own power during further development was great in the field of architecture, but unattractive in sculpture and insignificant in painting. The Novobrechman art is the art that gave birth to those huge temples with colossal cone-shaped or pyramidal towers, which we call pagodas, and sculptural images of countless gods and goddesses who have come down again from heaven, and with their many heads and many arms they make an impression of something monstrous. In terms of painting, the less one can recognize in this art of self-manifestation of life that the often mentioned miniatures belonging to him owe their origin only to the era of invasion of the Brahmanian world of Islam with its influence.

An integral part of the newly-born art is also the art of the Jaina sect, which achieved supreme prosperity after the suppression of Buddhism, thanks to the fact that this sect was able to reconcile the main Buddhist views with the recognition of the entire Brahmanian Olympus of gods and demigods. However, an attempt to isolate from the medieval North Indian art a special art of the Jaina has not yet succeeded, as well as trying to recognize the various architectural styles in the temples of various Brahman gods, of which Vishnu and Shiva temples were built more often than Brahma.

Fig. 565. Kailas in Ellora. By Le Bon / A modern photo

First of all, the Brahman artists adopted from the Buddhist cave structures, and ceased to round out their back side in order to replace the dome-shaped Dagobas with quadrangular shrines. They endowed their temples built in the rocks with all kinds of architectural and plastic decorations much more abundant and luxurious than Buddhist artists did; the ceiling supports received from them more massive and heavier forms, with the four-sided rods of the pillars sometimes passing into a wide pillow at half their height. By this, the architects strongly and fantastically expressed that the pillars bear the brunt of the whole mountain.

The most famous of the Brahman cave temples are located on the island of Elephant, near Bombay, in Ellora and Badami, in the western ridge of the Indian mountains, and in Magavellipura, south of Madras. Here the Brahman cave architecture made a very bold step, starting not only to hollow out the rocks, but also to process them from the outside in such a way that it produced a semblance of buildings standing under the open sky. Monolithic temples, excised from the whole rock, thus can be considered as real works of landscape architecture. The most important structures of this kind are the five famous monolithic temples on the seashore in Magavellipur and the even more famous Kailas in Ellora (Fig. 565). The five temples mentioned are carved out of loose cliffs; their interior has never been finished; Kailasa, trimmed inside, is cut from the slope of the mountain in such a way that it stands completely separate, as if in a huge drawer without a lid, separated from its walls by corridors 30 meters high. The neighboring rocks are dug by grottoes and galleries, bridges lead to them, the corridors widen in places and form courtyards. All exterior and interior walls of the quadrangular parts of this remarkable structure, which have flat but stepped roofs, are divided into compartments by pilasters and niches and decorated with figures of gods and animals of various sizes and in a diverse grouping. Everywhere the cult of Shiva and Vishnu is expressed, to which this wonder of the world was dedicated, large parts of which appeared in the VIII c. n e.

Fig. 566. The plan of the temple in Aivulli. According to Ferguson

Fig. 567. The plan of the temple in Pittadkul. According to Ferguson

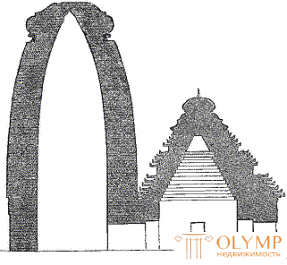

How free-standing temples originated from simple Buddhist cave temples, which were closed by a semicircle, about this better and most clearly give an idea of the plans of small temples in Aivulli and Pittadkul in Western India (Fig. 566 and 567). The first of them, which can be attributed to the VII century AD. e., despite its external colonnade and cella inside instead of dagoba, still quite closely resembles the underground temple in Carly with respect to the plan, and the second, built perhaps a century or two later, already represents the quadrilateral plan, square cella and colonnade later big Brahmin temples. Here, above the cella, as it happened then, everywhere, a huge tower already rises on a quadrangular base, which in general takes the form of a high multistage pyramid in the south of the peninsula after the North Indian ancient Buddhist tower in the Gaia; from the outside it tapers towards a rounded tip, also forming a slight curvature. The shape of these cone-shaped towers can be given by the concept of a section of the so-called black pagoda in Konarak, in Orissa (fig. 568). This figure shows one of the features of all the purely Indian arches, vaults and domes, namely the construction of them from the horizontal rows of stone, moving inward one above the other. The Indians almost completely neglected the laying of arches and vaults of concentrically arranged wedge-shaped hewn stones, even after the Mohammedans brought this method of building their domes with them to India. But the natural consequence of horizontal roofing and laying of arches was the predominance of horizontal lines in the dismemberment of the exterior of Indian towers and domes; perhaps even the expansion of the capitals of the columns with cantilever attachments is in connection with this construction technique.

Fig. 568. The section of the black pagoda in Konarak. According to Ferguson

With the further development of Indian architecture, a simple pagoda with a cella and a nave undergoes various modifications. The various shrines or chapels are connected into one whole, the number of towers and domes increases, the rooms for pilgrims (chultri) become an integral part of large temples; huge halls with columns appear, sacred ponds, and the courtyards are surrounded by colonnades. The quadrilateral formed by the walls of the sanctuary becomes too small: a second quadrilateral is constructed around it, a larger one, around the second - the third, and sometimes the fourth around the third. But the entrances in all these walls are made constantly in the form of luxuriously ornamented gates, and over each gate - especially in South India - one of the huge, stepping pyramidal towers rises, giving the whole structure a peculiar magnificence.

Indian architecture does not tolerate bare, unoccupied wall surfaces. They are divided into parts by protrusions and depressions both outside and inside buildings, blocked by pilasters, revived by niches or covered entirely with ornaments, borrowed from jewelry and resembling filigree work, then consisting of parts of plants that go into the game of lines, then representing Plastic images of people and animals are abundant. In the columns and pilasters, there is also an endless variety of fantastic forms. But here, everything has a known meaning. The more deeply the researchers peer into the architectural monuments of India, the more light is brought into its primitive artistic jungle. At present, hardly any serious researcher will repeat what Ritter said in “Geography”, published in the 1950s. XIX c.: "Nature and art, the measures of people, animals, gods and plants, are here in a state of still embryonic chaos."

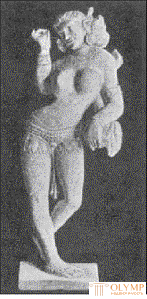

The temples in the area of Orissa in the northeast of the peninsula, simple in plan, squat and massive, are made of skillfully hewn sandstone without cement grease, and, however, some of their parts are connected with iron clamps. Above the sanctuary and entrance galleries cone-shaped towers rise, tapering upwards, but with a convex outline and a flat extension on the top. The forms of plastic ornamentation of these structures are extremely diverse. It is hard to imagine anything more characteristic of a mannered, soft, overly free processing of forms in Indian sculpture than a female statue originating from a temple in Bhubaneshwar and located at Le Beaune, in Paris (Fig. 569). The most famous of the temples of Orissa are, in addition to Bhubaneshwar (VI, VII and X centuries), in Konarak (X century) and Juggernaut (XII century).

Fig. 569. A female statue from the temple in Bhubaneshwar. By le bon

In the north-west of India, temples often have, in addition to the same cone-shaped towers, flat domes made of horizontal rows of stone according to the method we spoke of; but their main difference from the temples of the northeastern part of the peninsula consists in an abundance of columns and pilasters. In the X and XII century temples in Khajuraho and Gwalior, the walls are even cut through by colonnades, giving ample access to light and air. The white marble Jain temples on Mount Abu, dating back to the 11th and 12th centuries, are especially animated by pillars in their internal premises and courtyards. Plastic decorations of their walls, ceilings, pilasters and columns amaze with such decorative luxury, which the luxury of the most magnificent Gothic works of this kind can hardly match: the impression of petrified jewelry work imposed on the petrified carpentry is obtained.

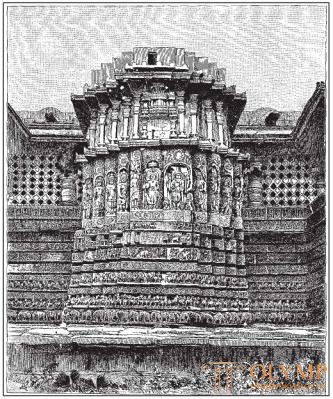

Indian architecture has taken on a special character in the heart of the Deccan, in the area of the ancient princes of Chalukya. In this Chalukin style, as Ferguson called it, only one star-shaped steep pyramid, usually topped with a stylized flower or vase, rises above the central temple of the temple, which has a star-like shape in plan. Luxurious plastic decorations cover the temple. Among them, strips of the frieze, decorated with rows of animals and surrounding the entire temple starting from the basement in horizontal rows, stand out especially sharply. The lower frieze always represents elephants, the second - lions, the third - horses, etc .; sometimes above all these horizontal rows of animals, such as, for example, in the famous temple in Halebid, there is a wider strip, divided into parts in the vertical direction by niches, of which in each is placed on the statue of God. The most magnificent of the temples of this kind, to which the Halebid temple (Fig. 570) must be counted, are located in the province of Mysore (Mysore) and built between 1000 and 1300. n e.

The architecture of the Indian pagodas in some respects is most magnificently developed in the actual Dravidian, or Turanian, south of the peninsula. The Dravidian style plays a major role in the Novo-Barakhman art of India: high four-sided pyramidal towers are distributed in it, consisting of many gradually decreasing tiers; they are found here in a greater number above the portals than above the cellae of the temples. This style belongs to the famous large temples, consisting of a series of quadrangular fences, from the outside increasing and increasing, which testifies to the gradual expansion of the shrines; It is here that the pilgrim halls (chultri) are transformed into huge open spaces - into the so-called thousand-column galleries, which are sometimes in connection with ponds and filled with a whole forest of columns of extremely fantastic forms. The particularity of the rich plastic ornamentation of these temples consists of elephants, lions and horses standing on hind legs and supporting eaves like caryatids, which sometimes, for example, in the Vellore temple, serve as column foustés, sometimes as for example in the large Madurai pagoda , they were staged severally one above the other at the same pilaster in the distorted guises they received in the ancient Indian animal epic.

Fig. 570. Part of the Halebid temple. By le bon

Fig. 571. Riders replacing pilasters in the large Syringamo pagoda. Kohl

Most often there are lions ready to jump, but often horsemen on horsebacks; finally, the gaps between the pilasters occupy entire hunting scenes, as we see in the large Syringham pagoda (Fig. 571).

From the 10th to the 15th century, a temple was built in Chidambaram, from the 14th to the 15th century. - a large pagoda in Thanjavur (Fig. 572, a), from the XIV to the XVIII centuries. - a large pagoda in Madurai. The most extensive of these temples, the aforementioned large pagoda in Syringame, on which stands 14-15 massive outpost, dates from the XVII and XVIII centuries.

The Indian architecture of the palaces in the Novobrahman millennium stands out somewhat more noticeably than before. The most luxurious of the northern royal residences, belonging to the XVI century, is preserved in Gwalior. The smooth walls of this palace, lined with glazed tiles of Persian origin, are divided by standing at an equal distance from each other by tall round towers with small domes. On the contrary, the palaces of South India, such as Madurai and Thanjavur, for example, belonging to the later centuries, with all their luxury, are no longer built in Indian stone-and-beam style, but in Mohammedan vaulted.

Fig. 572. Indian art: a - a large pagoda in Thanjavur. By Le Bon; b - Brahmin deity. Relief from Ellora. From the photo

We are already familiar with the new-born sculpture in its connection with the Indian architecture of the same era. Even idols cannot be imagined apart from their surroundings. Images of Brahman gods with four, with six and even with eight hands, as, for example, in one high relief from Ellora (b), due to their enormity already in relief make a heavy impression, and in round plastics they are completely unbearable. Free Indian plastic is mainly limited to the production of small sculptures, and it repeats the same primitive types, as evidenced, by the way, by the often found statues of the ancient goddess of beauty Sri, who is again in the Brahman Pantheon in the face of Lakshmi and who, receiving a different look and different the names are always distinguished by the same signs - the exaggeration of the features of the forms of a female physique, the same influence of poses and an excess of gold jewelry.

Throughout the entire life stock of Indians, it can be concluded that they have been skillful in art and craft industries since ancient times. Indications for this are found in their ancient poems. But then in many branches of applied art, Persian and Arabic influence distorted purely Indian forms beyond recognition. Almost only metal works can be considered in the history of national Indian art.

The iron column of the ancient Persian-Indian style, standing in the courtyard of the Qutab mosque in Old Delhi, is attributed to the 4th century. n e. Its mere existence proves that the Indians knew how to forge Europeans to forge pieces of iron of considerable size. A copper vase is kept in the London Indian Museum, on the spherical surface of which an engraved image of Prince Gautama’s solemn procession stretches around it, before it became a Buddha (see fig. 564, d); both at the place of its location and in style this vessel should be referred to a later time than the 3rd c. n e. This drawing is one of the most important works of ancient Buddhist art that we only possess. The golden crab from Kabul, adorned with statues of saints between niches with raised circular arches, located in the South Kensington Indian Museum, belongs, perhaps, to an earlier pore; but it is a characteristic monument of Roman Buddhist art of Gandhara.

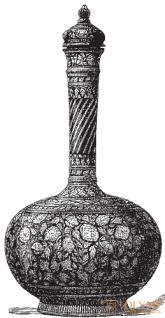

By the late time are Indian metal products, which still enjoy fame within their homeland. Famous vessels for water with long necks from Kashmir and Lucknow (Lucknow), covered with gilded ornaments on a silver background, are attributed to the Mongolian technique. Silverware of South India, embellished with embossed relief images of gods and monsters - apparently of native origin. But it was much more common in India to decorate steel and iron products with gold and silver inlays, or “damask” them, that is, insert gold or silver in the form of plates or wire into iron. This technique, the so-called bidri, was brought to Pyatirechye (Punjab) to the highest degree of perfection, as can be judged by the vessel with silver wire display (Fig. 573); but magnificent examples of this kind of work were found here and there in the south. Enameling, metal coating with colored glaze, was also practiced in India hundreds of years ago. Lagor, Lucky, Benares produce famous enameled bowls, but in the Muslim-Indian taste.

Fig. 573. Indian vessel with silver wire inlay. By Birdwood

С производством в Индии ювелирных украшений знакомят нас многочисленные их образцы, встречаемые еще в древнейшей индийской пластике. Уже в ней находим мы украшения для ушей и носа, браслеты для рук и ног и нарядные, составленные из цепочек и щита с гримасничающей физиономией шейные и нагрудные подвески для женщин. О постоянстве индийской традиции свидетельствует то обстоятельство, что украшения этого рода, исполненные в старинном вкусе, до сего времени выделываются в некоторых местностях Индии, мало затронутых европейской цивилизацией. Филигранное производство в Индии, одна из наиболее распространенных в ней отраслей прикладного искусства, появилось несколько позже. Мастера, изготовляющие серебряные филигранные вещи, не только служащие собственно для украшения, но и такие, как, например, табакерки, чашки и разная утварь, существуют доныне почти в каждой индийской деревне.

Determining the general nature of Indian ornamentation is not entirely easy. At first we find motifs in it, apparently borrowed from wooden buildings and wicker fences; then these motifs are joined by motifs peculiar to goldsmiths. At the same time, stylized linear and vegetative ornaments of the great Western arts brought from outside are gaining their place. At the same time, as an independent phenomenon of the Aryan north of India, a whole series of life-full forms emerged, taken from the local flora, but only brought to the plane with a fine sense of nature and a great sense of style. And here, next to the sacred lotus flower are the flowers and leaves of other plants; The figures of animals — tigers, elephants and antelopes, peacocks, and other birds — are intertwined with them — less often, human figures. The ornamentation of the Dravidian south treats flowers somewhat more schematically and local animals are often replaced by stylized fairy-tale monsters. In the developed Indian monumental decorative art, architectural motifs and figure plasticity predominate to such an extent that real ornaments at first glance almost disappear under their weight. But upon closer examination, we find that here too the main role is played by animal and plant motifs adapted to the decorative purpose. Even the rows of elephants, lions, horses, bulls and birds, filling with themselves whole friezes, produce, whatever their symbolic meaning, the impression is, above all, of animal ornamentation; and floral ornamentation is combined here, as in Western art, which probably influenced it, with wavy ribbons, forming curly arabesques full of stylish beauty. As regards the decorations on the works of the later art industry in India, one should be careful not to take Arabic-Persian forms as Indian ones. But in the end, the well-known tropically ardent and yet natural sense of style connected, on the basis of Indian ornamentation, a wide variety of elements, thus forming a whole that gives the impression of unity.

If we continue to assume that from the very beginning Indian art borrowed from the neighboring artistic worlds a lot of decorative particulars, then with a retrospective look at it we will not be deceived about the national content of India’s Buddhist and Brahmanian art. Not only will no one look for foreign designs for an Indian stupa, an Indian cave or monolithic temple, for any Indian pagoda in its entirety, but almost every individual Indian statue taken at random, will turn out to be Indian from head to toe heel; even Indian ornaments, considered in their entirety, are full of purely Indian originality. And no matter what we say about this art of Front India, it must be admitted that there were centuries in the early Middle Ages, when more mature and more naturalistic art flourished in Hindustan than in any other country.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)