The idea of the possibilities for the manifestation of color in its seven contrasts, which could be obtained from the previous sections of the book, now makes it possible to visually build a clear common system of the color world as a whole. Figure 3 depicts a twelve color circle, which is based on three primary colors — yellow, red, and blue — in their gradual transition from one to another. However, this scheme is not sufficient for a comprehensive overview of the entire color system. Instead of a circle, the same ball is needed, which was already presented by Philip Otto Runge as the most suitable form for color systematization. The ball is an elementary volumetric and symmetrical form, allowing to fully express the diverse properties of color. It allows you to make a clear picture of the law of complementary colors and clearly show all the main relationships of chromatic colors, as well as their interaction with black and white. If we imagine a color ball transparent, at each point of which there is a certain color, then we will immediately have the opportunity to present all the colors in their mutual subordination. Each point of the ball can be determined using its meridian and its parallel. For a clear idea of the color order, we need six parallels and twelve meridians.

On the surface of the ball, we put six parallels located at the same distance from each other and forming seven zones, and perpendicular to them, from the pole to the pole, we draw 12 meridians. In the equatorial zone, in twelve identical sectors, all the pure colors of the twelve-part color wheel are located. The polar zones are covered with white at the top and black at the bottom. Between the white color and the equatorial zone of each pure color, two stages of its clarification are successively located. From the equatorial zone towards the dark pole, we also give to each pure color two, but now darkened steps. Since each of the twelve pure colors has its own picture of the transition from light to dark, the steps towards white and black should be calculated for each color separately. Pure yellow color, for example, is very light and therefore its two clarified tones are very close to each other, while both darkened are very far from each other. Violet is the darkest of the purest colors and its lightened shades are considerably distant from one another, while the darker ones are very close. Each of the twelve colors should be brightened and darkened on the basis of its basic nature. Thus, we get two clarified and two darkened color circles, in each of which different colors have a different lightness. So, in the first lightening belt, the yellow color will be much lighter than purple, that is, in each belt all twelve colors do not have the same lightness.

Since the color ball cannot be shown when illustrating in three dimensions, we are forced to project its spherical surface onto the plane. If you look at this ball from above, then in its center we will see a white zone, which is enclosed between two belts of clarified shades, and half of the equatorial zone of pure colors. Looking at the color ball from below, we will see a black zone in the center, then two darkened areas adjacent to it and half of the equatorial part of pure colors.

In order to immediately see the entire surface of the color ball, we must imagine a darker hemisphere cut along the meridians and projected on a plane. As a result, we get a twelve-pointed star, shown in Figure 48. In its center is white. Adjacent to it are zones of clarified ones, followed by a zone of pure and two zones of dark colors, with black at the very end of the rays of this color star.

In Figure 49 we see the overall surface of the color ball. In its equatorial zone, there are pure colors that are gradually lightened and merged with the white belt in two stages. The same happens in the opposite "hemisphere", where the pure colors are also gradually darkened in two stages and become black. In Figure 50, a similar process is shown on the back of the ball and its entire surface thus becomes fully enveloped.

If we want to understand what is happening inside the ball, we must make its cut.

Figure 51 shows a horizontal section of the color ball at the equator, where we notice a zone of neutral gray in the center and a ring of pure colors on the outside. In the two zones between pure colors and gray are dark tones of blends of complementary colors. If we take two opposite colors of the equatorial zone, we get all the degrees of darkening, which were presented in Figures 23-28 in the section for additional colors. Such cross sections can be made along the lines of any five belts of the ball.

In the center of the ball along its vertical axis from the white pole to the black passes a series of gray tones. Our image is limited to seven levels of clarification, and therefore the fourth stage of gray tones should correspond to the average gray tone between white and black, and this gray color forms the middle of the ball. A similar gray color can be obtained by mixing any two additional colors.

Figure 52 shows a vertical section of a color ball over a red-orange-blue-green color zone. In the equatorial part of this section, on the left is the blue-green color and on the right - red-orange in their extreme saturation. Then, in the direction of the central axis, two stages of their mixed variants go, and the whole equatorial chain as a whole is gradually lightened to the white pole and darkened to the black one. You should pay attention to the fact that the degree of clarification and darkening of the steps should be equal and correspond to the gray tone of each step.

Exercises with color gradations in horizontal and vertical sections improve our understanding of color. In the horizontal rows, pure colors are organized, in the vertical rows their gradations are given in the direction of lightening and darkening. This systematization allows us to develop our sensitivity to color, both from the point of view of its perception, and from the point of view of the sensation of degrees of lightness and darkness of color.

The color ball makes it possible to present:

Suppose we have a magnetic needle fixed in the center of the color ball. If we direct the end of the arrow to any point of the ball, then its other end will be directed to a symmetrical point and a color that is additional to the first. If the end of the arrow points to the second lightness level of red, namely pink, the other end of the arrow will point to the same level of darkened additional green color. If we direct the end of the arrow to the second darkened stage of orange color, namely to brown color, then the other end of the magnetic arrow will show us the second level of clarification of blue color. Thus, we learn that not only the opposite colors, but also the degrees of their lightness are closely interrelated with each other.

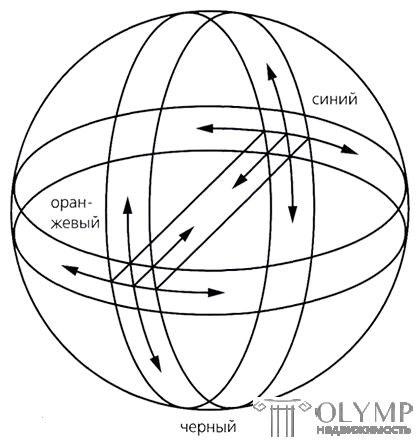

Figure 53 shows the five basic ways to transition between two contrasting colors. If we want to work with a pair of additional colors, for example, orange and blue, and start looking for colors that combine them, we must first localize both of these colors on the color ball. Orange, located on the equatorial line, will move to red and then to purple, this is in one direction, and in the other - to yellow and green, turning into blue. These are horizontal color movement options. But the same orange, following the meridian, will be combined with blue through light orange, white and light blue, in one direction, and in the other through dark orange, black and dark blue. And this is the vertical way of their interconnection.

If you follow the color ball from orange to blue in diameter, both complementary colors can be combined using gray or other mixtures of orange and blue in the following order: orange-gray, gray and blue-gray. And this is the diagonal way of their interaction. These five main directions will be the shortest and simplest lines connecting two complementary colors.

If we assume that this systematization eliminates all the difficulties in mastering color, then this is not so. The world of color has incredible inner possibilities, the wealth of which can only partially be reduced to elementary systematization. Each color in itself is a whole cosmos. But here we must be satisfied only with the presentation of its elementary foundations.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)