1. Overview of the development of English architecture

Political instability in England of the XVII century slowed down the development of national architecture. Over the course of a century, architectural art has been developing within the framework of the French and Italian Renaissance with the borrowing of classical and baroque motifs; also often found gothic. The most prominent English architects of the period were Inigo Jones and Christopher Rehn.

Embracing in the consciousness of his power, the British lion made a speech in the seventeenth century into the arena of struggle. In state life, England became the leader of the nations; the free spirit of exploring the three stars - Bacon, Locke and Newton - eclipsed with their rays the main luminaries of most European countries; in poetry, precisely at the beginning of the century, Shakespeare's best creations appeared: Hamlet, Lear and Macbeth, the only ones among the poetic works of that time that are still exemplary. It cannot be said that English culture is not mature enough to compete with all other countries in the educational arts as well; and indeed, the English architecture of the XVII century stood on a par with the architecture of the rest of the Germanic countries of Europe, if not exceeded it; on the contrary, the visual arts of England, arrested by the internal struggle raging in it, remained in this age in a state of minority.

True, the English architecture of the 17th century, following an insurmountable flow of time, abandoned national traditions in favor of a skillful, even stately feel, imitation of a semi-classical, semi-baroque late renaissance of Italians and French; but it has learned to adapt a new, alien language of forms to its own ecclesiastical and secular needs; but alongside the classical late renaissance, the gothic undercurrent also did not cease in England during the entire seventeenth century. Blomfield described it in detail. The church of John in Leeds (1632–1633) is characteristic, a two-nave church divided by lancet arcades, with an open ceiling, with late Gothic carvings in stone and wood carvings resembling the language of the forms of the “German” Renaissance. A still fairly clean late gothic is also at Wadham College (1610–1613) and on the beautiful staircase Krist Church College (1640) in Oxford; on the contrary, the church (rebuilt) Saint Catherine Three in London (1628), wide Gothic, with openwork carvings whose windows are separated from each other by Corinthian pilasters, exhibit a distinctly mixed style.

Even the two great English architects of this century, Inigo Jones, who served the pre-republican and Sir Christopher Wren - of republican England, could not quite get rid of the light remnants of Gothic architecture.

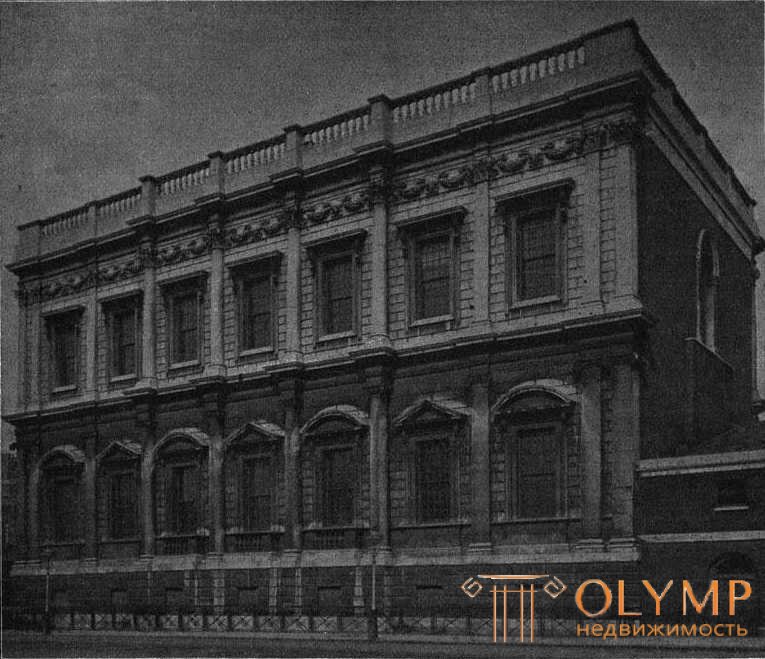

Glorifying Inigo Jones (1573–1651); as Shakespeare of English architecture, they detract from this the very world significance of the great playwright. But he really was a master craftsman who followed the paths of Serlio, Vignola and Palladio, whom he taught in Italy. His only Gothic building is considered to be the Lincoln-Inn Chapel in London, consecrated in 1623. His best works were the designs of royal palaces in Greenwich (since 1617) and White Hall (since 1619). The first, with the exception of the classically simple Queen's Villa (1635), were later executed by Ren and his successors, while the ambitious projects for White Hall were never fully implemented. Only the main hall, Banquet House, with the ceiling painting by Rubens, was executed and preserved. This two-story, dissected at the bottom of the Ionic, Corinthian pilasters and semi-columns at the top, a magnificent building, could not be lost in Venice or Vicenza. All individual forms are stately, strong and noble individually, and therefore, in English, they feel.

Fig. 188. Banquet House in London. built by Inigo Jones

Then followed the small church of Paul in Covent Garden (1631 to 1638), the only decoration of which is its stern Doric pediment, the porch behind which the dome rises. In his later years, Jones also participated in the construction and restructuring of a known number of rural castles of English nobility. His participation in the construction of the castle of Count Pembroke in Wilton, where the main hall with its walls, decorated with hanging garlands of fruit among the frames, makes an impression of a classic and at the same time English one. Clear completeness, strength and nobility of forms are distinguished by all the structures of this master. His pupil John Webb (1611–1674) built a project of Inigo Jones noble in his simplicity, decorated with a gable portico, Göndersbury House in Middlesex.

Fig. 189. Christopher Wren. Cathedral of sv. Paul's in London

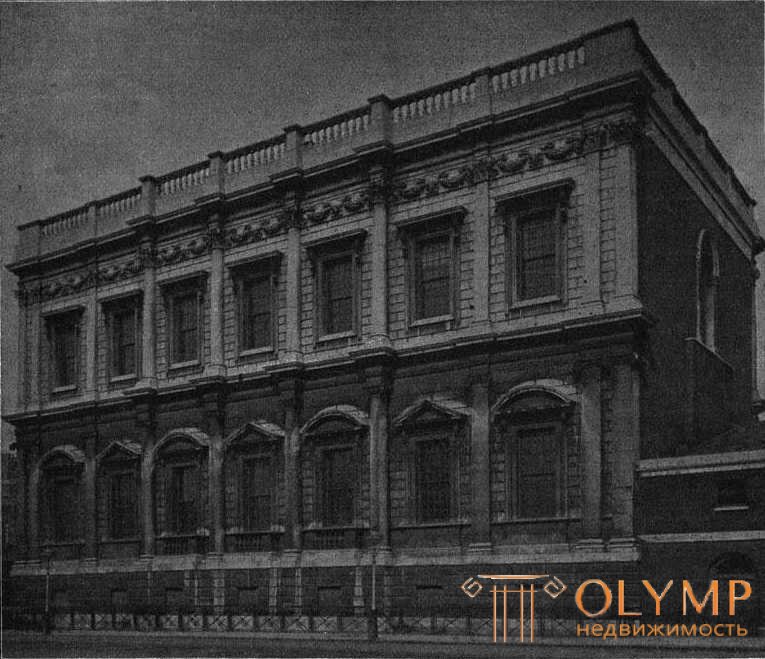

Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723) was not in Italy, but visited Paris. Therefore, its late renaissance is closer to the French than to the Italian. In any case, he is more rationally calculating artist than Jones, and already because more national English, although Baroque in general, but not in separate forms. The weight of Rena’s architecture is astounding. The fire in 1666, which destroyed the vast expanses of London, opened up an extensive arena for its activities. In addition to the large cathedral of St. Paul, his best building, between 1670 and 1711. He built at least 53 London city churches, which each time gave a new and yet solid form, applying more and more new versions of the motives of the backwaters, covers and empors of the Protestant preaching churches. The powerfully stretched palace in Greenwich, where Sir Christopher, with the help of Webb, and later Gauksmur and Vanbro, his deputies, continued to implement Inigo Jones projects, as early as 1694 was turned into a famous maritime hospital. Its front facades with protrusions and depressions, high Corinthian double columns and gables connecting both floors, resemble the facade of the church of Sts. Peter Madern in Rome. Of the royal palaces, only the René annex (1690–1694) to the ancient castle of Hampton Court, built of brick, dissected with hewn stone and producing a wide but heavy impression with its medium-spreading pediment, remained intact.

Fig. 190. Christopher Wren. The interior of the Cathedral of St. Paul's

The finest buildings of Rena also belong to the courtyard of Trinity College, Oxford and the classical, downstairs Tuscan, above Ionian, library of Trinity College in Cambridge. But his main glory is based on church buildings. Cathedral of sv. Paul's in London, built between 1675–1710 at one time under the direction of Ren, belongs to the grandest church buildings on earth. The central building as originally designed was never implemented. True, the building now stands has a domed top above the main sredokrestiy, which is given the greatest possible autonomy, but with its three-nave choir far to the east and further stretched to the west by the longitudinal hull, extended from the porch into the second transept, it gives the impression of a longitudinal construction. Separate forms, mostly of the Corinthian order, are sharply and strictly marked; Baruch ornaments are applied only here and there. Outside, the building seems to be a two-storey one, although the upper floors above the low aisles are no more than the stretch walls. The main facade consists of a portico with six double Corinthian columns in the lower floor, four in the upper and two richly dissected towers on the sides of the western facade. The main dome, dominating the building, narrowed like a cap, consists of two parts. The top of the dome stands on the drum, surrounded by a crown of columns, and the half-heel ends with a crowning slender flashlight.

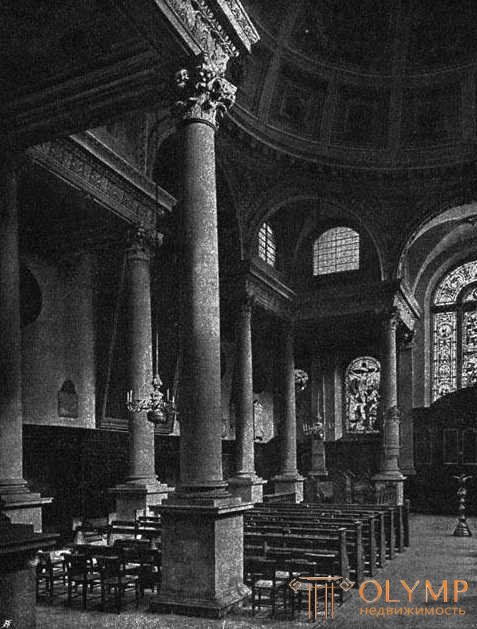

It is clear, majestically and calmly reigns a giant building on the sea houses of the world city. The remaining London city churches of Rena are distinguished from the outside mainly by their always different towers or domes. The gothic master towers supplied the churches of St. Dunstan in Caste (1698), Saint Mary Aldmeri (1711) and of sv. Michael in Cornhill (1721), joined by a gothic tower with Krist Choch College at Oxford. The domes possess the church of sv. Antonina, Saint Mary Abcech, Saint Sweene, Saint Stephen, Saint Mildred. The most famous Renaissance Renaissance towers are located in Saint-Meri-le-Bou (1680), still captured by gothic experiences in the supporting arches under the extremely high octagon of the columns, and in Saint Bride (1701–1702), the tower of which is still upward and turns into a spire rows of decreasing galleries. The domest Church of Saint Stephen (Wallbrook), easily raised to the Corinthian columns, has the most beautiful interior. Ren's versatility, always remaining itself and introducing a new thought into each new task, is astounding. She rarely enthralls and fascinates the viewer, but each of his creations excites surprise.

Fig. 191. Saint Stephen Church in London, built by Christopher Wren

Of his followers, Edward Germaine, the builder of the “royal” new exchange, completed in 1669, deserve only a few remnants in the new building of 1844, and William Telmen, the builder of Chatsworth (1681), the duke's lush rural castle Devonshire. Both main floors of the Chatsworth are dismembered, above the lower floor, into rustic, with Ionic pilasters reaching to the height of both floors, turned into columns under a protruding middle pediment.

In addition to Rena, John Wanbrough (1666–1726), also known as the author of comedies, introduced into the construction of palaces a clearly expressed, rather scenic decorative, rather than strictly architectural, peculiar style. He didn’t care about the beauty of the distribution of the individual rooms of his vast buildings, nor about the artistic performance of coarse, free-standing individual forms. He had in mind only a perspective general impression of his spacious, with huge front courtyards of palace buildings. His best buildings - Casta Howard (1702-1714), the estate of Count Carlyle, and Blenheim (1715), the residence of the Duke Malboro - reveal all the advantages and disadvantages of his art.

On the contrary, the real student of Rena was the rival and successor of Vanbro Nicholas Hauksmoor (1661–1736), to the most remarkable buildings of which belong to the Gothic-style towers All Sauls College, and to the best works, except the courtyard at Keynes College in Oxford with its beautifully overlapped entrance dome Hall, - the church of Christ educational house and the church of sv. George in Bloumber with their magnificent porticoes. Inigo Jones's style was transferred to Scotland by William Bruce, builder of the Hoptoun Hous Palladian Rural Castle (1698 to 1702), Ren’s style by William Adam, Vitruvius Scoticus author, modeled on the pattern that appeared already in 1717 by Vitruvius Britannicus Kolen Kem Kem Kem, Kem Kem, Kem Kem, Kem.

The false classical English late Renaissance spread at the end of the 17th century to the most distant corners of the United Kingdom.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)