The study of French building art owes its success to the work of Bertie, Choisy, Davilera, Detleler, Dussieux, Gurlitt, Guilmar, Lance, Leschevalier-Shevignan, Ruyet and Darcel, but especially Heinrich von Geymuller. Since it received its own academy later than other arts, it initially developed partly in the spirit of the high Renaissance Bramante and Palladio, partly in the spirit of the academic-classical striving for Roman antiquity.

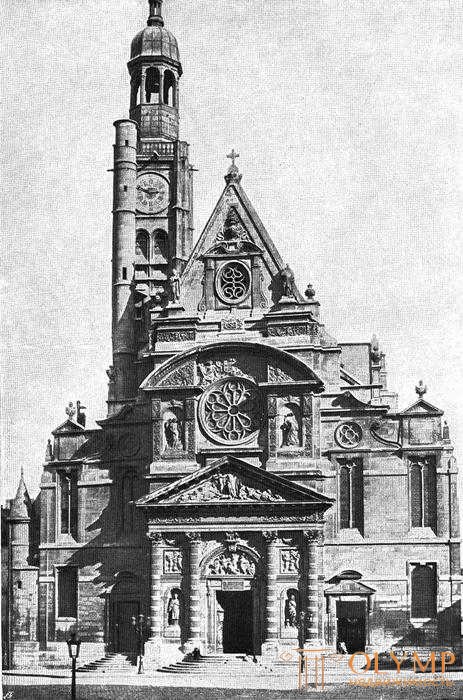

Fig. 110. Church of Saint-Étienne on the Hill in Paris. From a photo of Levi in Paris

The latest offspring of the mixed style of the “French Renaissance” are the new buildings: the picturesque facade of the town hall in La Rochelle (1605), supported by more ancient semicircular arcades, then started in 1610, still with high and sharp gables, with a Gothic window rose over the heavy columnar portal to the rustic façade of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont in Paris, as well as the still beautiful, despite its columns of three orders, the medieval-looking, front side of Saint-Pierre in Auxerre. Gallo-Frankish heritage is in some cases retained and high roofs of XVII century Gallo-Roman architecture, now taking the form of "cut" mansard roofs (named after the architect Jules d'Arduin-Mansart) and consisting of a steeper lower and flatter top. The impression of a Gallo-Frankish, if not Dutch, is also produced by the style of brick houses, lined with roughly hewn stone, on the Place du Vosges and on the Dauphin Square in Paris, which was then mainly implanted in rural castles. In the interior decorations of the French palaces and in the framing of windows and doors, as in the area of a secondary and looser, Gamemüller is distinguished by a “fancy” (“bizarre”) type of ornaments from the “baroque” decorations. Under the first, it means the further processing of fine-cut, elegant, sometimes naturalistic Italian forms of Bramante and Raphael jewelery, including grotesques; and under the "baroque" - those more massive, similar to leather, or dough rolled, wrapped or wavy jewelry, which were originally used by Michelangelo, received further development in the Netherlands and from there in the form of cartouches and curls turned into a decorative ornament, hence were transferred to France, where they were always practiced with a great sense of proportion. The “quaint” (“bizarre”) direction is already evident in the door frames of the Hotel Sully, beginning of the XVII century, blooms in the Hotel d'Ormesson (de Mayenne; 1680), it overpowers even the Baroque element in some large Lebren ceiling decorations and finally reaches its highest peak in many of the ornaments by Daniel Marot (1660-1718), published in photographic photographs of Jessen. These ornaments and similar to them by Jean Beren Sr. (1637–1711), who introduced wavy and wriggling lines into the medium also straight and broken by an angle, constitute the foundations of the Louis XV style. The ornamental motifs of one of the courtrooms of the Palace of Justice in Rennes now give some insight into transferring Beren’s style to the architectural decoration of the planes. Although the direction of the Baroque with its thick rounding forms characterizes the style of Louis XIII, it remains in the French building art only a side and undercurrent. It draws attention to the side door decorations already in the church of Saint-Paul and Saint-Louis in Paris (1627–1641), is deployed on the facade of the church of Mary in Nevers and is particularly brilliant in the “altars and fireplaces” of Barbe engraved by Bosse (1633 ). Even in the strict early days of Louis XIV, this element of the Baroque is on the portal of the Toulon Town Hall (1655–1657) Puget and in various parts of the large Laubren ceiling paintings. The third sideline, called Gamemüller, is real-rational, refuses, as far as possible, from bequeathed ancient or Novorim individual forms, wanting to obey only reason and own impulse, but never conduct it as consistently as our modern direction. The best examples of this side direction are the external extension of St. Mary’s Church on Saint-Antoine Street and the Saint-Denis Gate on Parisian boulevards. Both structures, of course, have a French character for the most part.

Fig. 111. Saint-Denis Gate in Paris. on the project of Francois Blondel. From a photo of Levi in Paris

The main classical trend, ancient and Novorimo with its church domes, which were used only from the time of Louis XIII, facades decorated with columns and semi-columns, which eventually came to a prim pomp, was dominated by Louis XIII and XIV throughout the century.

However, these trends, the main and secondary ones, are quite often found in various works of the same master, so that the artists, while remaining the main bearers of development, are at the same time dependent on him.

Fig. 112. Salomon de Bross. The facade of the church of Saint-Gervais in Paris. From a photo of Levi in Paris

Of the architects who flourished in the era of Louis XIII, namely from the younger members of the artistic families Ducerceau and Metezo, we are interested in Jean I Andrué Ducerceau (earlier 1590, died 1649), the builder of the mentioned Hotel Sully; and junior Clement Metezo (1581–1652), the creator of the single-nave, with Corinthian pilasters, longitudinal corps of the Oratorio in Paris. More detailed evaluation deserve, however, Jacques Lemercier and Francois Mansart.

Jacques Lemercier (circa 1585–1654), who studied in Italy, was one of the most prolific and fantasy-rich architects of his time. He was the favorite architect of Richelieu, for whom he built in 1627 a huge Richelieu castle destroyed during the revolution in Poitou, and in 1629 the magnificent, unfortunately, closed annexe, Palais Cardinal, later Palais Royal, in Paris. He was also the architect of Louis XIII, who had already commissioned him in 1624 to continue the construction of the Louvre. He continued to build the western wing and the western part of the north wing according to Lesko’s sketches, but he joined the western middle pavilion, the famous Pavilion de l'Horloge, according to his own plan. To many art lovers, this pavilion seems to be the finest piece of French architecture. In any case, together with Lesko’s wings, he represents a real “Louvre style”. The protruding Corinthian paired columns dismembered both lower floors, the pilasters dismembered the mezzanine under the second upper floor, whose double gable front in front of the dome-shaped high roof is supported by slender pair caryatids. All this is well adjacent to Lescaux's style, but in the columns of the passage Lemercier turned to de Bross's more powerful forms. Gamemüller claims, contrary to Perate, that Lemercier built the old castle of Louis XIII in Versailles, later absorbed by the gigantic castle of Louis XIV. In the Marble Courtyard (Cour de marbre), a part of its façade is preserved, one of those brick facades with frames of hewn stone that characterize the style of Louis XIII.

Lemercier also participated in the construction of churches. The construction of the classical dome church of Val de Gras, started by François Mansart, he continued, after a quarrel with Mansard with the authorities, to the height of the inner main cornice; He supplied the church of the Oratorio of Clement Meteso with a semicircular apse and an oval domed building above the choir in his own way. He also began to build a somewhat squat cruciform with a smooth dome, the church of Saint-Roch, but he performed only the choir with an oval, isolated chapel of Mary. We already know that in these oval forms, in and of themselves, the above-mentioned hidden baroque current is felt. The best church building in Lemercier was the church of the university building at the Sorbonne, which he built in 1629 for Richelieu. The Sorbonne Church (1635–1656) is not only the first truly grand domed church of France, but differs from most of its Italian sisters in the cutting of all its four facades. The space under the dome is a Greek cross with short branches, to which, however, in the east there is an adjacent chorus with side chapels and a protruding semicircular apse, and in the west a longitudinal nave with side chapels, so that the general plan of the lower base has a rectangular shape. This space is dissected by Corinthian pilasters. The dome rises on a high drum with windows. The steep rise of the dome is achieved by the fact that the head of the dome is not built of stone, but, as is customary in France, is a wooden blockhouse. Before the northern branch of the cross is a classic, resting on four columns, a porch with a pediment. The western facade is content with one gable over a narrower upper floor, dissected by Roman pilasters, while the wider lower floor is dissected by Corinthian columns. Corner turrets, appearing on the same foundation as the dome, are covered, like the main lantern, with “bell-shaped tops”. Considered as a whole, the building is distinguished by its classic unity, but with its well-thought-out construction, it acts more on our reason than on our living feeling.

Talented and more independent than Lemercier, Francois Mansart (1598 to 1666). In the Church of Mary on Sent'Antoine Street (1632–1634), he created a very independent small dome structure, which very little resembled its appearance as separate forms of ancient architecture, and inside it was round with eight pilasters under the dome, and quadrangular, if we take into account corner chapels, abundant in classic forms.

Fig. 113. Francois Mansart. Church of Val de Grasse in Paris. From a photo of Levi in Paris

It was Mansar who connected in general the strictest adherence to classical individual forms with the most noble own understanding of style. We already know that he also completed the project of the Vall de Grasse church, begun in 1645. After Lemercier, Pierre Lemue (1591–1669), the author of scholarly works on architecture, graduated from it (with the assistance of Gabriel Leduc) (died in 1708). ) and others. In essential terms, it seems that the project Mansara has been preserved. Ahead of the central space crowned with a powerful dome, there is a more significant longitudinal body, dissected by noble Corinthian pilasters under calm dull vaults. Behind the semicircular apse, however, is located one independent chapel of Mary. Adjacent to the noble façade is a porch projecting on two pairs of columns with a gable of the first floor, which is successfully located under the gable of the upper floor. The hidden current of the Baroque is reflected in powerful spiral volutes linking the narrower upper floor with the wider lower floor. In general, here too there is an impression of a cold and vigorous late Renaissance.

The French Jesuit style of that time and his representatives Étienne Martelange (1569–1641), to whom books by Charves and Bouchot were dedicated, and François Deran (1588–1644) combine Italian, part Flemish, as well as French late Renaissance XVII century, but more heavy and pompous form. Martelange, about the numerous Jesuit collegiums of which the present Gospice de la Charité in Lyon gives an idea, has a Roman style of its time with particular artlessness. Deran, on the contrary, leans towards the Flemish Baroque, as shown by its narrow, high three-story facade of Saint-Paul and Saint-Louis (1627–1641) and belt ornaments of curls and cartouches inside this church.

During the reign of Louis XIV, the architecture of France acquired the features of the so-called false classical style, as architects increasingly use antique forms; One of the most common elements is the Corinthian column. It was during this period that the main works on the creation of the famous Versailles Palace complex were carried out.

Majestic and magnificent, but at the same time colder, the French building art develops in the second half of the century under Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV, who in 1661 concentrated the rule in his hands. The best architects of this time who are interested in us, what are Levo, Blondel, Perrot, d'Arduen-Mansart, meet not only wall and ceiling decorators, such masters as Lebrun, whom we will meet in a number of painters, but also masters who, irrespective of the buildings erected by them, at first they followed in the footsteps of the older Dyuurceau, as architectural and ornamental engravers. We owe them the knowledge of many destroyed structures and a lively idea of the various phases of the development of ornamental art. These engravers-architects include Jean Marot (circa 1619–1679), engraving with his son Daniel Marot (1660–1718) numerous projects, erected buildings and decorative motifs, then Jean Lepotre (1617–1682), who completed thousands of artistic worksheets , samples for artisans in the style of a more rigorous French semi-baroque, and his brother Antoine Lepotre (1621–1682), an architect who gained fame for his building, Hotel de Beauvais in Paris, ingeniously adapted to an angular piece of land, but showing particular strength of invention in their ideal projects, in which the undercurrent of baroque quite often supersedes the upper classical trend. We have already mentioned that Daniel Marot and Jean Veren (1637–1711) are the forerunners of the rococo.

Now we must go to the above-mentioned great architects of the century, Louis XIV.

On the contrary, Levo since 1665, as the architect of Louis XIV, worked at Versailles, where, at the request of the king, a new magnificent building, surpassing all the castles of the world in grandeur and beauty, was to embrace his old, cozy hunting castle like a royal mantle. Gradually, under the leadership of the Left, new intermediate wings and yards emerged. Left also made a project of a powerful garden facade, resembling in many respects the unfulfilled Berninian facade of the Louvre. Of the eleven windows, the main building pushed back, two seven-window corner wings protrude, connected to the lower, arcaded floor divided by rustic, also into rustic, above which an open terrace stretches in front of the windows of the wide middle hull. The main floor, decorated with tall rectangular windows with oblong relief plates, is dissected by powerful Ionic columns and semi-columns. An attic with almost square window openings rises above the main eaves, and above it stretches, in front of an Italian flat roof, crowning a balustrade with statues. In this form, the facade of Levo is still in the figures in 1674.

In the field of church architecture, Levo led from 1655 the construction of the church Saint-Sulpice in Paris, the completion of which belongs to a later epoch, and from 1661 he performed again with his student Dorbe, almost Baroque, the College of four nations with its dome-wide oval the church, the current Institut de France Institute of France. The strict classical trend intensified in the Left only over the years. It received its solemn triumph in the coldly pompous facade of the Palace of Versailles.

The purest classic was Claude Perrot (1613–1688), a physician and architect who emerged victorious in the competition for the eastern facade of the Louvre. The laying of the facade of Perrault took place in 1665, and in 1680 it was over. The facade is dissected by two corner protrusions and a middle, surmounted by a flat triangular pediment. Bernini borrowed the idea to arrange a basement in the form of a basement and tie the entire upper building with a magnificent Corinthian order. Each of the three projections carries four pairs of columns or pilasters. Between the protrusions or the rizalits in front of both backs, the wings are six pairs of double columns, and together with the corner columns they are so far from the walls that they form a real colonnade in front of them. Therefore, talking about the "colonnades" Perrot. According to Gamemüller, this facade decorated with columns is the only, after the facade with the towers of Notre Dame, an architectural work in Paris that gives the impression of something monumental and majestic in the highest sense of the word to the visitor from Italy. We also admire his prideful pomp, but, of course, she does not touch or care for us. A similar but adjacent colonnade provided Perrault and the south side of the Louvre, facing the Seine, and for her sake raised the attic Lescaux on two sides, turning it into a full floor, so that only the rear wing of the entire building still retains the old classical, rather than pseudo-classical style of the Louvre .

Fig. 114. The facade with the colonnades of the Louvre in Paris by Claude Perrot. From a photo of Levi in Paris

Jules d'Arduin Mansart (1646–1708), great-nephew of Francois Mansart, closes a number of the great French architects of the XVII century. His son-in-law Robert de Cott (1656–1735), who often worked with him as an apprentice and assistant, as an independent leader in his field, already belongs to the next next time and style. Jules d'Ardouin-Mansart is still a fake classic, although in his decorations, performed together with Lebrun, he softened the severity of his style and Blondel in favor of a freer flight of fancy, and in his most intimate works he tried to combine French elegance with false classic pathos. In the architecture of private hotels, which we can not list here, it was considered with the desire of the era to a more convenient distribution and arrangement of rooms. From it goes the placement of mirrors over fireplaces, the replacement of wallpaper panels in small rooms. Cut "roofs", with protruding dormer windows, got its name from his name, although he did not invent them.

Fig. 115. The military hall in Versailles by Jules d'Arduin Mansard. From a photo of Levi in Paris

The early major work of Mansara, the unpreserved castle of Claes, near Versailles (1676–1679), the graceful shelter of Countess Montespan, was a horseshoe-shaped pavilion. The Marly's amusement castle, which followed him, represented a small village house, enveloping the average domed space modeled on the “Villa Rotonda” Palladio. Its annexes inside and outside the Palace of Versailles continued until 1682, when the courtyard moved to Versailles. Some of the wings on the asymmetrical, facing to the courtyard and the city, he covered the side of the palace with high roofs. He did not expand the garden façade of Levo, as claimed, but completely transformed it in the sense of a general impression, closing the wide middle terrace in front of the retreating main building with the famous mirror gallery, stretching seventeen windows, decorated with Lebrun. The facade was thus straightened, and its high rectangular windows, after the elimination of the relief plates above them, were turned into semicircular, arched. Inside the palace, some of the halls, such as the Military, the Peace Hall and the “bull's-eye” hall, so named for the narrow oval window, were decorated by Garduin’s designs with multi-colored marble walls framed by pilasters or half-columns with luxurious gilding, in the garden he built Ionian "colonnade" and Tuscan, decorated with rustic, wall greenhouse.

Since 1688, the Grand Trianon Garden Palace in Versailles, a one-story building with flat ceilings, with double columns and balustrades, with ceremonial and living rooms for temporary stay, followed.

Fig. 116. The palace chapel at Versailles by Jules d'Arduin Mansart. From a photo of Levi in Paris

In Paris, Jules d'Ardouin-Mansart contributed significantly (1684 to 1686) to the development of modern art by setting up large areas of cities, surrounded by houses of corresponding size, such as the Place de Victoires circular square and the rectangular Louis-the-Great square (now Vendome). By himself he is in the building of churches. The Versailles Notre Dame (1684–1686) forms a Latin cross with a simple dome over a medium cross and Doric pilasters in front of the arcades of a longitudinal ship. Its palace chapel in Versailles (since 1699) is peculiar, since its front side merges with the facade of the palace, and only the longitudinal sides and the choir continue freely inside the palace courtyard. Two-storey, like all ancient palace and city chapels, it is surrounded on all sides inside, in the lower ground floor there are arcades on the pillars, and in the high upper floor there is a gallery of empors with classical, canelated Corinthian columns carrying a direct entablature. The best church building of this master is the Paris Cathedral of Invalides, whose high dome (1680-1706) became a sign of Paris: proportionally conceived central building with a high, two-story, cylindrical lantern on a square two-story case and a slim, triple, made in the upper parts of wood This building has slightly protruding middle rizalits topped with gables. The interior forms an eight-column Corinthian circle in the middle domed space with four branches of the cross and four corner chapels. Outside, the ground floor is decorated with Doric, upper Corinthian pilasters. The protruding column portal of the main facade only in the upper floor is crowned with a flat triangular pediment. The neck between the dome and the lantern reinforces the impression of grace inherent in this one-of-a-kind and exceptionally highly developed masterpiece of classical French architecture at the turn of the century.

Fig. 117. Jules d'Arduin Mansart. The Church of the Invalides in Paris. From a photo of Levi in Paris

We cannot part with the French architecture of this era without glancing at the garden art that is inextricably linked to it. What was achieved by the French of this era, in connection with the Italian architecture of the villas and the Dutch construction of canals, the independent adaptation of their results to their land holdings and extensive palace plans remains the guideline to the present day in the architectural stylization of the landscape surrounding the large palaces. It has long been recognized that large monumental buildings need similar stylized gardens with their terraces and staircases, water pools and wells, carpet beds, alleys and geometrically regular leveled and trimmed tree plantations to appear in full glory of their architecture. Only gradually, as they move away from the castle, do the correct lines of such gardens pass into the freedom of the natural landscape. In the middle of the century artisan-gardener Louis XIII Claude Mollet wrote about his art. The first steps in the development of this art are represented by the Garden of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, in which Salomon de Bross himself took part. In the second half of the century, Andre Lenotre (1613–1700) brought this new art to perfection, first in the gardens of the castle of Vaux-le-Vicomte, then especially in the gardens of Versailles. It is the vastness of the French palaces of this era, partly due to and demanded by their gardens, that was perceived by Europe as worthy of attention and imitation, and the general impression produced by works of French architecture of the XVII century is unthinkable without their gardens.

The French architecture of this century lacks the inner warmth and fullness of independent living, but it still fascinated wide circles with its clear, rational magnificence.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)