1. Overview of the early period of development of the arychitecture

At the beginning of the century, classicism dominates Dutch architecture, but, remaining within its framework, local structures have original features. In parallel with it, the Dutch national renaissance style is developing. By the end of the century, the prevailing influence is acquired by French architecture, and there are also some Flemish features.

Three main phases followed one after another in the seventeenth-century Dutch building art, the history of which was laid out in detail by Galland. During the first third of the century, the national Dutch Renaissance flourished, independently reworking individual motifs of Mediterranean art, but using them only by the way, creating works that generally stood on their own feet. During the second third and somewhat longer, classicism prevailed in Dutch construction art, following Vignola, Palladio and Scamozzi, and even attempted to go further, inventing and applying the invention to greater simplicity, which, however, soon turned into coldness and lethargy. During the last quarter of this century, and in Dutch architecture, sobriety and pomposity led a fruitless ghostly struggle, the end of which put French influence penetrating into Holland.

Using the fruits of trade and exchange generated by youthful freedom, Dutch cities grew and expanded, whose watery streets, with numerous bridges, bordered by roads and rows of trees in front of peaked houses, look so peculiarly picturesque and cozy. In many cities, new churches, town halls, city post offices, meat, grain and wine trade were erected, new rows of beautiful residential buildings with high gables appeared everywhere. The brick building on the ground piles, which arose on local soil, was the main kind of architecture. Residential buildings were often built entirely of bricks. Buildings of ashlar were rarely come across. But now, as before, a mixed style of brick construction with ashlar cladding was preferred, which is the Dutch national style.

We traced the movement to the beginning of the XVII century. For the delightful Hague Town Hall (1565), in which only the upper floor was decorated with a side gable with semi-antique pilasters and columns followed, in a similar style, more clearly dissected and more strictly united, crowned with elegant towers of the Town Hall in Bolsvard (1614), from the middle of the facade which is picturesque the main parts are with a high pediment and a magnificent porch. Only upon closer inspection can we see that the slim, fluted, connected at the top of the cornice belt, the half-columns of its upper floor mimic the Ionic one. Dutch construction from the base to the top of the tower. The magnificent Town Hall in Zutzen (1618–1627) has protruding pilasters only in the upper floor, in this case Tuscan ones. Directly beside it stands, as befits, a beautiful tower of a wine trading house with a rich, national-baroque portal of the basement, with a double porch leading to the first floor hall on the semi-circular arches, with four slender, free-standing corner columns that facilitate the transition from the lower octagonal floor to the upper quadrilateral, with a flat octagonal dome, the convex top of which crowns the building.

The original architectural buildings, the protruding pilasters of which almost do not impress those and have only added gables, belong primarily to the meat market in Gaarlem (493), an example of the national Dutch high renaissance of the beginning of the new century (1602–1603), with a gallery divided into two nave Tuscan round columns. Above the round portals and rectangular windows are fan-shaped arches of hewn stone. Peculiarly shaped, decorated with protrusions of hewn stone and candelabra vials step pediment. All in solid, dense, cohesive masses, and yet everything is picturesquely closed into one.

The stately home of the Golden Scales in Groningen (1635), with tall windows still retaining the remains of a Gothic openwork carving, with wide shells of its unloading arches — a specially Groningen motif — has Tuscan protruding pilasters only on the rich main pediment bounded by curved lines.

Buildings completely devoid of pilasters orders, like the aforementioned John's Hospital in Goorn, are - a powerful, with a stepped gable, the house at Galguevere in Leiden (1612), a mint with a baroque pediment in Enkguizen, and most burgher houses, in which now you can still distinguish - and the northern Dutch style. In northern Holland, there are no, at least at the beginning, Dordrecht false dissections by means of projections rising from the ends of the graduation stones, but the stepped pediment is enriched with oblique extensions (arrows). The Flemish gables are those richly decorated with semi-baroque motifs, usually gables elongated upwards, which are in Dutch processing at the Gaarlem butchers' house.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameWhat Hendrik de Keyser of Utrecht (1565–1621), the founder of the Amsterdam school, accomplished in the young capital on the Amstel, was what Leven de Key achieved in Germany. Also known as a sculptor, de Keyser is considered the eye master of the heyday of Dutch architecture. He was a disciple of Cornelis Blomart, then developed in the same direction as Liven de Key, in conclusion, to prepare the way for classicism. The execution of his projects was often in the hands of Cornelis Dancerts de Rey and Hendrik Jacobs Stets, then his associates, then his rivals. Its later development is reflected in the essay Modern Architecture (Architectura moderna), published in 1631 by Solomon de Bray. In the Amsterdam construction of residential buildings, to which de Keyser lent his mark, he introduced the Dordrecht dismemberment by false projections. From 1595 he was an Amsterdam city architect.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameThe transition of dominant positions to Protestantism caused a revision of the principles of building churches and thus contributed to the formation of national art. In the Dutch architecture of that period, its own version of classicism was created, with independent borrowings from ancient sources: in particular, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns were widely used.

Extremely important was the activity of de Keyser for the development of reformed church architecture. The choir, in which the reformed preaching churches did not need at all, was eliminated by him from the very beginning. Otherwise, his Amsterdam temples testify to the successes in the church architecture “South Church” (Zuiderkerk; 1603–1611) - a simple, rectangular hall, without a transept, divided into three naves by two rows of Tuscan columns, five in each, covered with a simple wooden arch.

In the “Western Church” (Wesietkerk; 1620–1638), de Keyser moved to a richer structure with two transepts, which, although not protruding as a rectangle of the main plan, are even more powerful over the low lateral aisles. Internal supports - Tuscan three-column beam posts. The upper wall is decorated inside with Ionic pilasters, outside with Ionic semi-columns.

In the end, de Keyser came to the conclusion that the central building is most suitable for the Protestant preaching church. He built his “Northern Church” (Noorderkerk; 1620–1623) according to the plan of the Greek cross. Tuscan round columns stand in front of the pillars of the middle cross. A bell tower rises above the center of the cross.

Among the early large secular buildings of this master is his courtyard of the Ostindi House (1606) in Amsterdam, the old national brick-and-stone style of which mocks all purely classical forms. Elevated, crowned with small balustrades, gables and magnificent portals are decorated with still rather strict, but thin twisted ornaments. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (1608–1611) of the same master, unfortunately, has not survived. The full contrast to the courtyard of the “Ostindi House” is its facade of the town hall in Delft (1618), as it returns to the classical, two-story, Doric below, Ionian above dismemberment by pilasters. The last Amsterdam buildings of de Keyser, giving the impression of eclecticism, belongs to the representative House with Heads, and later the commercial school. His disciples and followers soon turned to completely different paths.

The well-developed, scientifically imitative classicism, followed by the architects, was replaced in the second third of the century by the imbued Baroque nationalism of the Dutch building art. This classicism, independently drawn from ancient sources, has nothing in common with the more inflated French contemporary classicism. It is clear in itself that certain artistic personalities act as its creators and bearers.

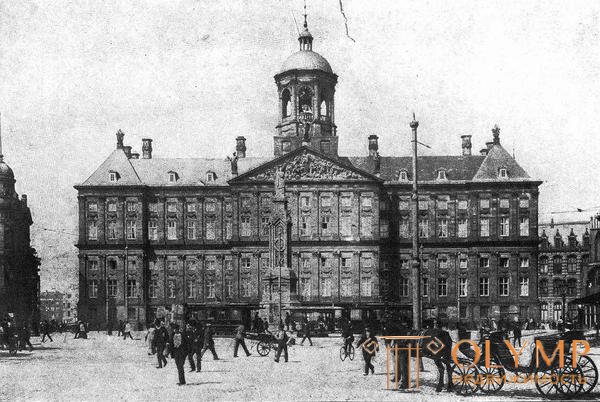

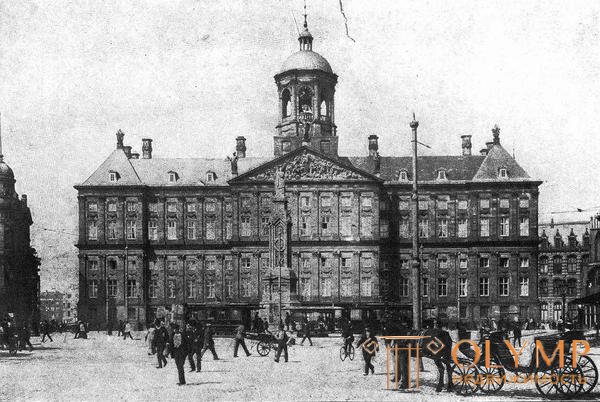

Its founder was Jacob van Kampen from Amsterdam (1598–1657), who visited Italy and settled in Amsterdam around 1630. Already in the mentioned “Architectura moderna” of 1631 there is an image of its main structure in the classic imitative style in Amsterdam - the widely spread Koyman house on Keizersgracht, which finally breaks with the style of high gables and fake arcades. Above the eight-window face with the semicircular, without decorations, the tops of the doors of the basement floor, the floor is placed with Ionic, then with Corinthian pilasters and, finally, the Doric half-floor; everything is clear, understandable, flawless; there is not even any decoration on the portals, which was often considered the main thing until then. The most important work of Kampen is a powerful new town hall in Amsterdam (1648–1655), which, quite significantly, became the residence of the Dutch kings in the 19th century. From the outside, it is as monotonous as possible. And here is a simple basement with arched entrances without decorations; above it are two high, 23 windows each, of exactly identical Corinthian main floors, in which two half-floors are entered. A dome tower with a eight-sided arched arcade rises above the seven-window building, surmounted by a wide Greek triangular pediment. A more artistic impression is made by the interior with a grand distribution of space, wonderfully dissected marble halls, with rich plastic and pictorial decorations, to which we will return. As a whole, this building in any case represents a complete contrast to the direction of the Dutch painter Rembrandt with his mighty works of the same time.

Fig. 159. Jacob van Kampen. Town Hall in Amsterdam

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameThe third in the union, Phillip Vingboons (1608–1675), is the favorite architect of the well-to-do Amsterdam burghers of his time, with whom he built many town houses and summer houses. The modest appearance of his buildings with pilasters, the classicism of which is already of a very dubious nature, he seeks to eliminate with the frequent use of sharply colored cartouches of the Utrecht native Crispin van der Passe, the author of the book “Officina arcularia”, published in Amsterdam in 1642. Country houses Wingbouncons usually decorated with Corinthian pilasters and temple gables. His palace by Jan Huydekuper on Zingele in Amsterdam was built in 1639. The completely imitative classical construction of this genus, the so-called "Trippenguis" by Klorenirsburgval (1662), is attributed to Justus Wingboons.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameDuring the last quarter of the 17th century, only a few new public buildings of artistic significance were built in Holland. The town hall in Enkguizen, built in 1688, shows how independently this epoch was trying to surpass the monotonous boredom of the outside cutting of the Amsterdam town hall. Amsterdam residential buildings, too, are becoming increasingly poorer in art and decoration. At the same time, interior spaces are becoming more and more pretentious, and are becoming richer decorated in styles that change from decade to decade, which are now being influenced by the French decorative style of Louis XIV. The decoration of the courtyard of the Hague Grafsky Palace with the so-called “Treveskammer” (1697), for which the predecessor is the decorative style of Versailles palaces, is characteristic.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)