With the struggle that pope had to wage at the time under review, then with the anti-pops, then with the German emperors, now with the Roman nobility, then with the Roman people, the Eternal City was deprived of the peace and prosperity necessary for the independent development of art. Occasionally we encounter here new, fresh trends, but in general, Rome in this era was fed by old, already distorted traditions.

The early Christian trend continued to hold in Rome mainly in architecture, which almost did not take part in the “Romanesque” movement and rather sought to return to a more strict, ancient style. The main type of the temple remained the ancient Roman basilica; both the old scheme of the plan and the flat wooden ceilings or open rafters were kept; still predominantly used antique columns. By the beginning of the XII century, the later rebuilt church of Sv. Clement (San Clemente), in which 16 dissimilar antique columns are interconnected by semicircular arches. But the Roman basilica of the middle and the end of the XII century. and the first half of the XIII century. returning to the rectilinear entablature over the columns of the longitudinal body; such are, for example, the magnificent church of Santa Maria in Trastevere (1139) with a highly elevated transept resembling the Romanesque churches, San Crisogono, the ancient basilica restored in 1128 with the triumphal arch supported by the ancient porphyry columns in Rome, San -Lorenzo Fuori Le Mura (St. Lawrence) with her narthex, the ionic entablature of which rests on six antique columns. Other churches have changed their original shape due to later extension of the bell towers or “gallery of cloisters”, that is, a monastery courtyard or garden, surrounded on all four sides by an open gallery, whose semi-circular arches rest on double luxuriously ornamented columns. The indoor atrium of the graceful church of Santa Maria in Kozmedin belongs to the 11th century; then, in our opinion, its beautiful four-sided bell tower was built in seven richly divided tiers with double and triple arched windows (Fig. 133). But in the churches connected with the monasteries, the western atrium surrounded by porticos disappeared; it was replaced by the cloister's gallery on the south side of the church. Some Roman galleries of cloisters of this kind can be considered the most beautiful and original creations of Romanesque architecture on the banks of the Tiber. The gallery of the cloister at the church of San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura (circa 1190) with its single, unmilitary dwarf columns is still simple and somewhat heavy. The luxurious and graceful vast monastery courtyard of the church of San Cosimato (circa 1200), whose double columns have cupped capitals. But the greatest pomp is reached at the cloister gallery at the Lateran Basilica (1222–1230) and at San Paolo Fuori le Mura (1220–1241), where the marble columns of arcades and friezes are covered with a rich and multicolored mosaic of geometric patterns belonging to the patterns of the architectural ornamentation that as already noted by us above, it spread from Monte Cassino, on the one hand, in southern Italy, and on the other, in Rome. In the Eternal City, this kind of ornamentation, used besides cloister galleries also for altar fences, pulpits, door frames, floors, seats and candlesticks, gradually improved in the writings of so many generations of artists who had already proudly displayed their names in their works, achieved considerable severity of style and grace. In the frames and profiles, we see ancient forms, and in the inlays, carved from ancient porphyry and colored marble columns and dominating here over painted and gilded glass cubes, there is a great artistic taste. Roman works decorated in such a way became famous under the name of the works of Kosmati. But Cosmati is the youngest of the families of artists in which this skill was passed from father to son. A number of these artists begins with a certain master Paul (about 1090), his sons and grandchildren. From the earliest works, executed by really Cosmati, under whose hands mosaic ornaments then often turned into real mosaic pictures, one can point to the beautiful marble facing of the portal of the church of Sts. Savva in Rome (1205), the work of Jacob, the father of Cosma I. We will return later to Cosmati. From the number of works Kosmati XII. and the next decades of the XIII century, the best works should include luxurious floors in the churches of Santa Maria in Kozmedin (circa 1120), Santa Maria in Trastevere (circa 1140), Santa Maria Maggiore (circa 1150), San Lorenzo fuori le Mura (circa 1220), especially the stylish and elegant reading consoles, altars, railings, bishop seats and stuff in the Roman churches of San Clemente, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santa Maria in Cozmedin and Santa Maria in Araceli.

Fig. 133. Church of Santa Maria in Cozmedin in Rome. With photos Alinari

Neighboring regions of Rome also played a role in the history of the architecture of the era in question. Umbrian Proto-Renaissance refers to ancient motifs, as if reintroduced into the architecture of some Umbrian churches, but in fact never disappeared from Middle Italian architecture. The three-nave church of Sant'Agostino del Crocefisso, in the cemetery of the city of Spoleto, with its massive Doric columns and open rafters, resembles an early Christian structure, approaching an ancient Roman temple. Wonderful ornaments in the ancient genus on the facade of this church, as well as antique elements in the facade of the Spoleto Cathedral, are already mixed here and there with Lombardy-Romanesque.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play gameVery little can be said about the independent Roman and Umbrian plastics of this era. Even the ancient Roman relief ornamentation was supplanted, as we have seen, by flat ornaments borrowed from the East. Of particular interest are the sculptural decorations of a marble candlestick for Easter candles in the church of San Paolo fuori le Mura, made by masters Niccolò di Angelo and Pietro Vassaletto (circa 1180). The pedestal of this candlestick is all covered with rough reliefs depicting episodes of the earthly life of the Savior; in the ugly forms of these reliefs there is already nothing Byzantine, and only in the heads of the figures there are vague hints of ancient reliefs. The crucifixion of Christ (Fig. 134) is depicted so clumsily that it resembles the reliefs of primitive peoples. It seems that art is back to the times of its infancy.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play gameFig. 134. Crucifixion. Relief on a candlestick for Easter candles in the Basilica of San Paolo Fuori le Mura in Rome. With photos Mushyoni

Slightly more life in the curly decorations of the facades of Umbrian churches. But the images of evangelists and animals on the facade of the Romanesque Cathedral in Assisi are dry and lifeless; Atlantean figures on the gallery of the facade of the Cathedral of Spoleta and on the facade of the church of San Pietro in Tuscanella are shapeless and too miniature; abundantly and variably placed on the plane are the abundant sculptural adornments of the facade of the church of San Pietro in Spoleto, with their large symbolic reliefs, scenes from the life of the Apostle Peter and reliefs depicting the death of the righteous and sinners, made in schematic but fairly regular forms.

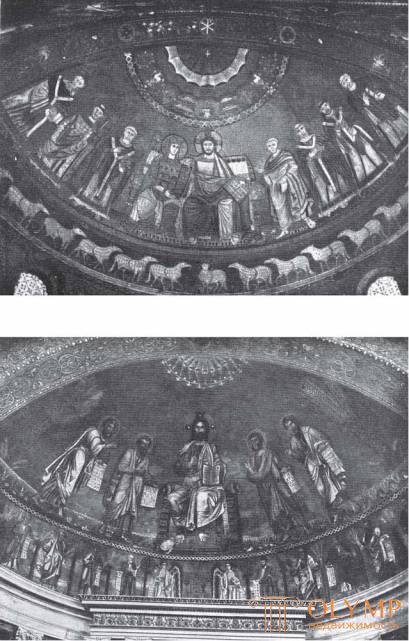

As for painting, Rome and the Papal States have already taken an independent, to a certain extent, participation in the development of this branch of art. Even the Roman mosaic, which, as we have seen, was in complete decline for almost two centuries, in the XII century, awoke to a new life. Especially remarkable are the mosaics of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere. A large mosaic on the vault of the apse (1148), which effectively dominates the other decoration of the church (Fig. 135), depicts the Savior and the Mother of God sitting on a throne, and a number of saints standing on either side of it. Thus, the image of the Virgin in the form of a queen gets a place in the main mosaic of the Roman church, but is moved somewhat to the side; Christ continues to occupy a central, honorable position. The mosaic background is gold; clothes shine also in gold, blue and blue; only the extreme left figure of the saint is in a red robe. With some Byzantine details of the composition, its main motive is new, in the spirit of the new time, and the poor, angular, though not deprived of the known breadth, forms are far from the Byzantine refinement of Sicilian mosaics of the same time. The content of the Byzantine character in its content is a rough apse mosaic in the church of Santa Francesca Romana, dating back to the 13th century. The Most Holy Virgin sat here on the throne alone, in a solemnly stately pose; but here too there is a deviation from the Byzantine composition: the Mother of God does not hold the Infant directly in front of him, and He stands somewhat at the side, on one of her knees. The return to Byzantine comes then under Pope Honorius III, who in 1128 wrote in writing to the Venetian Doge with a request to send him mosaic artists to decorate the church of Sts. Paul's The mosaic of the main apse niche in Sao Paolo fuori le Mura, performed by Greek or Greek masters trained by the masters (see fig. 135), the main image of which represents the Savior among the four standing saints on a golden background, though it is heavily restored, but in its present form she leaves no doubt about the Byzantine character of her design. The inscriptions in it, at least in part, made in Greek letters. Anciently Christian in composition in general, but Byzantine in terms of execution of details is a mosaic of the apse in the church of San Clemente, usually attributed (according to de Rossi) to the middle of the XII century, but more fundamentally attributed to Zimmerman’s era of imitation of Byzantine patterns, that is, the beginning of the XIII century. It is remarkable that the crucified Savior, whose figure is rather small compared to the large arabesques bordering the entire semicircular image, was presented for the first time in Rome with closed eyes and a bowed head, but His legs, resting on the crossbar of the cross, were still each individually.

Fig. 135. Mosaics of the apse in the medieval Roman churches: above - in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere; below - in the church of San Paolo fuori le Mura. From photos of Alinari

The opposite of this Byzantine or mosaicists working under Byzantine influence at the beginning of the 13th century was Kosmati, who also worked with figured images. Master Jacob and his son Cosma worked, as can be seen from their inscription, a round shield over the entrance to the former Monastery in memory of the liberation of slaves (now the villa of Mattei). The Savior sitting on the throne holds in one hand a white, in the other a black slave, whose only garment is an apron. This original by design and original work, unfortunately, is badly damaged during the last restoration of the building. The waist-length image of the Savior in a round medallion above the right entrance door of the Cathedral in Civita Castellana (1210) fits close to him in style; in the round, framed by a small beard, a little expressive face of the Savior, there is already nothing Byzantine.

Of the Roman frescoes, the latest painting of the lower church of San Clemente (see above, books 2, II, 1), painted in Salazaro, is especially noteworthy. Two scenes from the legend of sv. Clement: in the narthex - a miracle in the temple, depicted on the background of the sea, in the middle nave - the appeal of St. Clement of Syzinia to Christianity. The buildings are drawn quite correctly, the movements are directly felt, although not quite skillfully conveyed; in figures and heads one can see the desire to combine nobility with grace. The second fresco of the narthex, depicting the transfer of the remains of St.. Clement to the church gives us a complete understanding of the technique of this painting, with its dark blue backgrounds, black outlines that turn into costumes in white, and with weakly modeled red-cheeked faces.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play gameGame: Perform tasks and rest cool.2 people play!

Play game

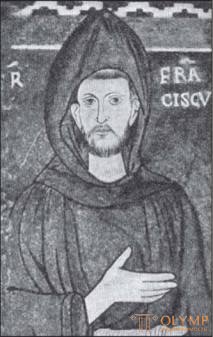

Fig. 136. The image of St. Francis of Assisi in the Lower Church of the Sacro-Spekko in Subiaco. Tode

St. Dominic (died in 1221) only a few warned St. Francis (died in 1226). Franciscans and Dominicans had an enormous influence on all subsequent church and artistic life, and although this influence was shown in full force only in the late Middle Ages, but as regards St. Francis, it was immediately expressed by his canonization (1228) by the construction of the Lombard-Romanesque Lower Church in Assisi dedicated to him; The frescoes adorning this church are based on scenes from the life of the saint, however, not earlier than the middle of the 13th century.

In the first half of the 13th century, some large Umbrian wooden crucifixes belonged, which make it possible to largely trace the development of art in the period under consideration. These original monuments are a special kind of Middle Italian easel painting. They testify that at the beginning of the twelfth century, the crucified Christ was depicted with separate feet nailed to the cross, with his head raised and eyes open, not as a sufferer, but as a triumphant Redeemer. The change that took place soon afterwards is explained, on the one hand, by the growing influence of Byzantine art, on the other hand, by the influence of the sermons of St. Francis, whose theme is often the image of the dying Savior. On these crucifixes, the face of Christ gradually assumes a suffering expression, eyes close, the head leans to the right shoulder, the body falls under its own weight. In parallel with these changes in the composition of the Crucifixion, although not so soon, the nailing of both legs, folded one on top of the other crosswise, with one nail, is a purely western feature. While images of the Savior triumphant on the cross cease soon after the first third of the thirteenth century, nailing both legs with one nail becomes common only from the last quarter of this century. The most important surviving Umbrian crucifixes of this kind by the very fact that Christ is represented on them alive, and his legs nailed apart, testify to a more ancient origin. A large crucifix in the main church of Spoleto, whose forms, which are excessively elongated, indicate the Byzantine influence reflected in it, is marked in 1187 by the name of the artist Albert. More Italian character, already on the rounded outline of the head of the Savior, has the famous crucifix in the church of St.. Klara in Assisi - the very thing from which, according to legend, the Savior spoke from St. Fancis. A comparison of these two crucifixes convinces us that, near the end of the twelfth century and in this branch of art, along with the direction strongly permeated by Byzantine, another, more independent, was designated.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)