When we enter the fertile soil of Tuscany, the cities of which in the middle of the XI century were for the most part independent, independent states, we recall the life-giving images of the ancient Etrur art and at the same time we anticipate all the brilliance followed half a millennium. Already in the XI and XII centuries. and in the first half of the 13th century, at least Tuscan architecture went its own way, which is of extremely important artistic and historical significance. True, just as the “Romanesque” movement was not able to bring Rome out of the rut of its old basilic style, this style remained, in its essential features, also in Tuscany. And here, during the whole period under consideration, basilicas with columns and a flat ceiling or open rafters were built; the arches overlapped in the temples only crypts and partly aisles. But a significant novelty in Tuscany was that the exterior walls of the basilica for the first time received a rich finish. In contrast to the flat decoration that came from the East, the walls, arched galleries or fake arcades of the facades were faced with white, black and green and here and there red marble slabs; in their sculptural decorations visible undoubted proximity to the late antiques. In Florence, this connection with ancient art seems so close that Florentine-Romanesque architecture, according to Jacob Burkgardt, is recognized as proto-Renaissance. However, with great reason we can see in it the continuation of ancient traditions than the revival, since the middle Italian architecture of this time constantly drew elements from the stock of ancient forms. What the Tuscan-Roman architecture lost in the organic coherence of the parts inherent in ancient architecture and in the understanding of individual forms, it compensated for it with its own delicate artistic flair.

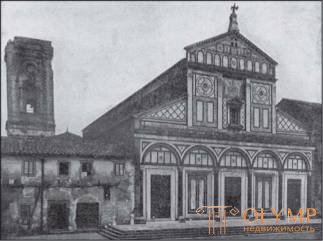

Fig. 137. Church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence. With photos Alinari

The main monument of this style in Florence is the charming church of San Miniato al Monte, outside the city, on the mountain, and the baptistery, in the very center of the city. The first is a sample of a basilica of Tuscan-Romanesque style, the second is a central structure. The difference from ancient basilicas and baptisms is here and there in facing the external and internal wall surfaces with two-color stone slabs.

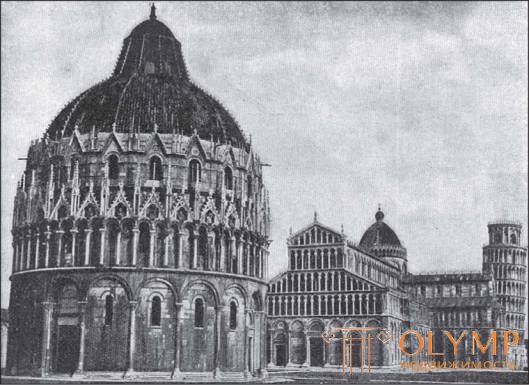

The church of San Miniato, built in the XI century, is a three-nave basilica without a transept, with an extensive crypt under the choir, which must be climbed through several steps (Fig. 137). The crypt is blocked by cross vaults, above the very church - open rafters of the roof. Corinthian columns between the naves in the longitudinal direction are connected to one another by semicircular arches. The place of every third column is occupied by a thick pillar, to which a half-column is attached on all four sides; The semi-columns, facing the middle nave, are taller than the others, and are connected by transverse arches over the middle nave. Inside, the top of the walls is decorated with simple geometric patterns of dark green marble on a white background, and the apse with elegant arcades on semi-columns. Outside, the front facade of the church reproduces its transverse section in noble proportions. The lower floor, wider, is dissected by five false arches resting on Corinthian columns. The gable of the narrower upper floor is supported by four fluted pilasters; between the middle pilasters, under a mosaic on a gold background, made in the Byzantine spirit, a window with a pediment was made, the side columns of which stand on Romanesque lions. Also characteristic of the Romanesque architecture is the eagle crowning the top of the pediment; but the figures of the "Atlanteans" (see vol. 1, fig. 320) on the sides of the fake-arched gallery under the gable are too tiny. Not all the details of this facade are organically interconnected, but in general it is effective and original.

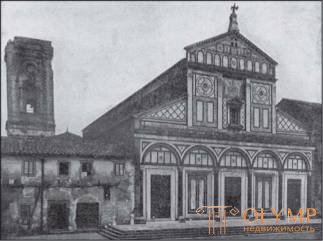

Fig. 138. Pisa Cathedral with a baptistery (in the foreground, left) and a bell tower. With photos of Brodgy

The Florentine Baptistery, which has come down to us almost the same as it was in the XII century, represents inside an octagonal space covered by a single dome. Antique Corinthian granite columns, set in niche-like recesses of the walls and connected with each other by a direct entablature, form the lower tier, and pilasters alternating with semicircular arcades, dismember the upper tier of this room. The exterior walls of the baptistery are complemented in the following centuries. Thus, the wide crowning eaves belong to the XV century, that is, the Renaissance; but slender pilasters located in several tiers (pilasters of the middle tier are connected by semicircular arches), and the facing of all main planes by rows of multi-colored plates are among the most charming inventions of the Tuscan-Romanesque style.

Fig. 139. The interior of the Cathedral of Pisa. With photos of Brodgy

Finally, the famous Leaning Bell Tower of Pisa, erected by the German master Wilhelm of Innsbruck and Pisan Bonann (construction started in 1174), is surrounded on each of the six upper floors by an open, laced colonnade. “The principle of the Greeks,” said Jacob Burkgardt, “to encircle the building with a colonnade, as a living expression of wall roundness, was transferred here with great courage to a multi-storey building; these are not just galleries, but an ideal lining of the tower, representing in its own way no less a victory over the weight of the material than the German Gothic towers ”. With regard to architectural details, the Corinthian capitals of the ancient style are often giving way to more simple medieval forms. The general impression made by this whole group of buildings, which were investigated by P. Schumann and some others, was that it was antiquity, reworked freely and in an original way.

Florentine style, which is exemplified in Florence itself, except for San Miniato, the old church of Sts. The apostles are also visible in the lower parts of the facade of the Cathedral of Empoli (1093) and, mixed with Pisan motifs, in some churches of Pistoia, namely in the cathedrals of Sant'Andrea and San Bartolomeo. The style of the Cathedral of Pisa, in Pisa itself expressed in a simpler form, for example, in the churches of San Frediano, San Sisto, San Pierino and already complicated by pointed arches in the beautiful small churches of San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno and Santa Maria della The back, more or less successfully imitated mainly the churches of Lucca. The often-mentioned church of San Frediano in Lucca, the preserved part of which, as indicated by Degio, really belongs only to the first half of the 12th century, has five naves, but is devoid of a transept. Three-nave and T-shaped, having a transept church in Lucca - Cathedral of sv. Martina, San Michele, Santa Maria foris Portam and San Giovanni. The peculiarity of these churches is that in the middle of the arcade galleries of their front facades there is not an arch, but a column, as in the two uppermost galleries of the Cathedral of Pisa. The main antique features visible throughout the churches of Florence and Pisa, in small towns, are beginning to disappear. The church of Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo enjoys great fame, the entire four-tier facade of which is turned into galleries on columns, which are growing up, due to the doubling of the number of columns, more and more closely. For the same reason, the columns of the upper row could not be connected by arches and carry the flat entablature.

Tuscan sculpture rises to a considerable height in the subsequent time, in the era occupying us, only its rudiments appear, on the study of which Shmarsov worked. There can be no talk in these rudiments of something independent of the ancient and Byzantine art. The relief with the image of Our Lady in the Church of Santa Maria foris Portam turned out to be a slave copy of a Byzantine relief on ivory. The font in the church of San Frediano in Lucca is an enlarged reproduction of one old Christian ivory box. And in other plastic figured images on Tuscan church facades, chairs and fonts one can see the desire to keep the old, mainly Byzantine tradition everywhere, and only in rare cases Tuscan sculpture at that time managed to revive this numbed tradition with the breath of a new life.

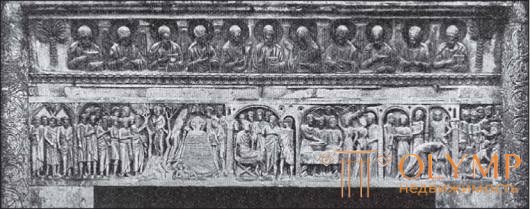

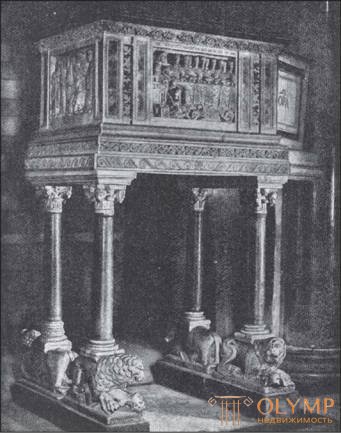

As examples of poor understanding of forms with loyalty to the Byzantine direction in general, you can point to the works of Master Gruamon and his brother Daodat, in Pistoi, The Last Supper over the northern doors of the church of San Giovanni-fuorchivitas (1162) and Adoration of the Magi side portal of the church of Sant Andrea. Between 1200 and 1250 Guido Bigarelli from Como, who worked, as we saw, in 1246 in the Pisan Baptistery, led Tuscan sculpture along the path of the conscious imitation of antiques, and this was at variance with the artistic aspirations of his homeland. From 1204 to 1233 he labored, with breaks, over his main work - the facade of the Cathedral of Sts. Martina in Lucca. In the pillars of this facade, entwined with animal figures, the influence of Upper Italian romance is felt, but the image of Christ sitting on the throne, on the portal gable, no less than shows the Bigarelli towards ancient art. He worked in 1199 in Pistoia, in the local cathedral, and after 1250 - on the chair of the church of San Bartolomeo in Pantano. For half a century, the style of his works remained the same. Elegant, but lifeless, this style tried to get closer to the ancient models performed by even the heads. Among the sculptors who, after Bigarelli, continued to work on the facade of the Cathedral of Lucca, was the master, who carved images of the months and scenes from the life of St. Martin on both sides of the average portal (1233), was superior to this artist in terms of the inner liveliness of the figures. Probably, the same master executed here a huge (more than in nature) image of St. Martina on horseback, with a beggar, which is an important step forward in the development of medieval plastics.

Fig. 140. Relief of the eaves above the eastern door of the Pisan Baptistery. With photos Alinari

When considering Tuscan painting until the middle of the XIII century, we again meet with the "Byzantine question." Vasari asserted that Italian painting of the time we were examining was languishing in the bonds of Byzantine and that Cimabue himself, a reformer of Tuscan painting, learned his art from Greek painters who were called to Florence by her government. This evidence of the father of the history of Italian art is often ridiculed after Rumor’s research. But we have already seen that Pope Honorius III in the first third of the XIII century called Byzantine mosaicists to Rome; as easily the Florentine government could invite Greek artists to Florence, at least for mosaic works in the baptistery. In any case, the fact that it was at the beginning of the 13th century that the Byzantine style gained dominance in Tuscan painting was not denied by Rumor, Strigovsky, Toda, Max Zimmerman, and others.

Fig. 141. Department of the Cathedral of Volterra. With photos Alinari

If we turn to mosaics here, our attention will first of all be focused on those performed between 1225 and 1230. mosaic altar niche in the Florentine baptistery. Francis monk Jacob, who worked on them, was brought up on Byzantine patterns, no doubt what his style of work does not allow. Колесо с Агнцем в середине держат четыре мужские коленопреклоненные фигуры, стоящие на (написанных) капителях колонн. Я. Буркгардт видел в них предков микеланджеловских аксессуарных фигур на потолке Сикстинской капеллы. Но украшения спиц колеса — византийские, равно как и изображения Иоанна Крестителя и Богоматери, восседающих на тронах среди коленопреклоненных мужских фигур. Богоматерь, представленная en face, держит Младенца прямо перед собой на коленях; надо отметить, что этот византийский тип изображения Богоматери является здесь в последний раз в итальянском искусстве.

Мозаики купола баптистерия исполнены отчасти столетием позже, но они не свежее и не лучше мозаик абсиды. Большой образ Христа в среднем круге купола — работы Андреа Тафи, которого Вазари называл учеником грека Аполлония и который отождествлялся с неким Андреем с греко-венецианского острова Кандия.

Впечатление византийских производят также неудачно реставрированные мозаики церкви Сан-Миньято во Флоренции. Мозаика алтарной ниши, изображающая Спасителя между Богоматерью и св. Миньято, принадлежит, вероятно, концу, а мозаика на фронтоне, со Спасителем, сидящим на престоле, началу XIII столетия. В декоративном отношении обе эти мозаики очень эффектны.

Fig. 142. Гвидо Сиенский. Мадонна. Икона в Сиенской ратуше. With photos Alinari

From the Tuscan frescoes, mention should be made of the church of San Pietro in Grado near Pisa, which decorates it. Thirty large frescoes on the upper walls of the middle nave represent episodes from the life of the Apostle Peter. Under them are portraits of the popes, and above them is a frieze with figures of angels. The main character of these unpractical images is Byzantine, but many Roman Christian features are inherent in them.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)