Lombardo-romance art we call the art of the valley of the Po and the eastern slopes of the Apennines to Bologna. Thus, in territorial terms, it extends besides Lombardy itself also to Emilia, and in some cases, as already noted above, its influence penetrates even the Apennines and conquers certain areas of Central and Southern Italy. Although the Romanesque architectural style of its most pure, consistent and harmonious development in areas lying north of the Alps, nevertheless Lombard architecture, first studied in detail by Darten and then Rivoira, most of the individual Romanesque forms, as we have seen (see. 2, II, 1), developed earlier than the North Romanian. It is possible that these forms, the prototypes of which we find part in Syria and Asia Minor (see book 1), were transplanted, through the medium of monastic art and oriental monasteries, on the one hand, through Ravenna to Lombardy, on the other - if we agree with Strigovsky - through Marseille, but, in any case, partly through Italy, - to France and Germany. Be that as it may, the fresh forces of the West poured new life into these forms and soldered them into a powerful whole. The same causes had the same effect in both the North and the South. Therefore, recognizing in many respects the primacy of Lombardy, we cannot, however, return to the now shared Rivoira old view that the Romanesque architecture has spread everywhere from Lombardy.

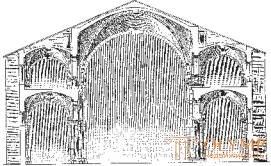

Fig. 143. Cross-section of the church of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan. By darten

We have already seen (see Vol. 2, II, 1) that a number of distinctive features of Romanesque architecture, what the walls were divided by blades and false arches, arch friezes and small arched columns galleries, could already take root in the Lombard architecture in the preceding time. Similarly, we meet before 1050, and, moreover, both in the south and in the north of the Alps, the Romanesque cuboid capital, rounded down in the form of a hemisphere. But only from the middle of the XI century did Italian and northern architects begin to dare what constitutes the main innovation of the Romanesque style, namely, to cover the arches of the middle nave; such a coating, where it was made by the cross vaults, gave a number of regular quadrangles adjacent to one another. The romance basils of this “connected system”, observed quite consistently, for example in the Piacenza Cathedral, are not as often found in Lombardy as they are in the north of the Alps. But the more freely overlaid Romanesque basil, whose plan instead of the old T-shaped form has the shape of a Latin cross (see Fig. 89), reaches a brilliant development in Lombardy.

This feature of the Romanesque style manifested itself completely in the original church rebuilt in the second half of the XI century (according to Rivaire - in 1046–1071). Ambrose (Sant'Ambrogio) in Milan (see her plan in Fig. 72). Only three niches of her choir belong to the construction of the VIII – IX centuries. The atrium, surrounded by a gallery with columns and pillars, as we see it now, was built no earlier than the 11th – 13th centuries. The longitudinal hull of this church (Fig. 143) is a three-nave one, without a transept, with an octahedral hip dome over the altar space, with two-level side aisles of almost the same height as the middle aisle and with the narthex opening into the atrium with five arches on each floor. Inside the temple, the large squares of the middle nave are covered with elevated and therefore having a dome-shaped cross vaults, the ribs of which are thickened with diagonal ribs. The supports of these ribs are slender tall half-columns, attached to the corners of massive pillars supporting the longitudinal and transverse arches. Between the main pillars are inserted two smaller arches, which, repeating in the upper tier, form small cross vaults over the side aisles and their empores. On the low capitals of the pillars, leaf ornament, schematized in the Byzantine spirit, is intermingled with the ancient Lombard weaving and animal forms (Fig. 144). Stylized acanthus curls, arc friezes and rows of flat stripes adorn other places. Especially curious monsters with bulging eyes on the rods of the columns of the main portal. Such figures of fantastic animals, which are purely external to the elements of the building, are a feature of the Lombard architectural plastics. That the Germanic race of the Lombards affects these bizarre forms seems to us not so unbelievable as it was believed at the time; This does not contradict the individual cases of the appearance of such forms in Central Italy, which must be explained precisely by the Lombard influence. For all its importance to the history of Romanesque architecture, the Milan church of Sts. Ambrose is not distinguished by the nobility of proportions that is necessary for the most remarkable building to be artistic to the fullest.

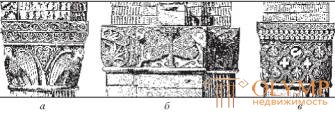

Fig. 144. Capitals of the pillars and columns in the church of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan. By darten

Among the basil with arches, the church of Sts. Michael (San Michele) in Pavia, in its architecture very close to the Milan church of St.. Ambrose, from which she is distinguished by the presence of a transept in it. The main part of the building belongs to the second half of the XI century, and the facade to the first half of the XII century. Of the other most important Romanesque churches of Upper Italy, covered with cross vaults, according to Degio's classification, churches with empores over the side aisles are richly divided by the Modena, Parma, Piacenza, Cremona and Borgo San Donnino. Among the basilicas with low aisles without emporos, the church of San Savino in Piacenza, the monastery church in Chiaravalle, near Milan, and San Pietro e Paolo in Bologna have a plan divided into squares; on the contrary, the spectacular churches of San Pietro in Cielo d'Oro in Pavia and the cathedral in Trient, on whose facades unstable “composite” columns [3] are striking, are built according to a freer plan. The facade with one gable and tiny arched galleries along its slopes are the churches of San Michele and San Pietro in Pavia, as well as the Parma and Piacenza cathedrals. The arched galleries of the choir of the cathedrals of Modena, Parma (fig. 145) and Murano are especially richly decorated with arcades. The most complex plan is the Piacenza Cathedral, the transept of which, apparently in imitation of the Cathedral of Pisa (see fig. 139), as well as the longitudinal case, has a three-nave one. Churches with the most beautiful octahedral domes include the Piacenza and Parma cathedrals and the churches of San Pietro in Cielo d'Oro and San Giovanni in Borgo in Pavia. In the architecture of the towers, the most developed forms were anticipated in the early Middle Ages by a pair of bell towers of the cathedral in Ivrea (973-1005); the two towers were supposed to, as an exception, decorate the unfinished facade of the cathedral in Borgo San Donnino (1080). In Lombard style, built in 1063, the only bell tower in Pomposa, near Ravenna. In the XII century, this style was followed by the builders of the bell towers at the church of San Zeno in Verona and at the Parma Cathedral.

Fig. 145. Parma Cathedral from the east. With photos Alinari

Fig. 146. Lombard capitals: a - from Modena Cathedral; b - from Piacenza Cathedral. By Degio and Bezold

Inside the Lombard basil with arches rather simple architectural forms prevail. Along with the Corinthian capitals and the imitating Corinthian, which dominate here, being in different variations (Fig. 146), we find, for example, in the Chiaravalle monastery church near Milan, in Sant'Abondio in Como, in San Pietro e Paolo in Bologna , in San Teodoro in Pavia and in the aisles of Modena and Povarsky Cathedrals, cubic ornamented capitals; Capitals with figures of animals and people are especially rich in the churches of Sant'Ambrogio and San Celso in Milan, San Michele and San Pietro in Pavia.

The central system of architecture, if you do not take into account the Bologna Church of San Sepolcro, which is an imitation of the Jerusalem Church of the Holy Sepulcher and built in the 1st millennium, found its use mainly in some baptisteries, outside and inside the extremely dismembered and decorated with galleries with columns and arcades. The octagonal baptisteries in Parma and Cremona are especially luxurious.

With all the monotony of the general artistic nature of the Lombardo-Romanesque architectural style, there is much difference and freedom in its details. He did not produce such certainly great, exciting soul of the monuments, which are in the Tuscan-Romanesque architecture of the Cathedral of Pisa, and in the Venetian-Byzantine Cathedral of St.. Mark; its historical significance in relation to the development of new forms is more important than its artistic merit; nevertheless, when looking at the church of verona of sv. Zeno and the Councils of Piacenza, Modena, or Parma Councils, one cannot but succumb to their charm.

The Lombardo-Romanesque plastics were mainly engaged in cutting stone reliefs and, above the capitals mentioned by us with figures of animals and people, endowed with church sculptures and portals with sculptural decorations. In general, it is higher than the Tuscan plastics of the same time, more free from the Byzantine tradition, more vital, and this, according to the dominant German science, owes the presence of northern, Germanic elements in it. The form of the name “Wiligelm” in one of the artists' signatures seems to indicate the German origin of the person who exposed it; but German names were generally used in Lombardy since the Lombards; they only testify to the Germanic impurity in the blood of the Lombards, who, having become Italians, in the 11th – 12th centuries felt themselves sufficiently independent to create new things on their own. In the aggregate of his works, the Upper Italian plastic of the time in question, to which Max Zimmerman devoted a special work, seems, however, more crude than the modern northern art.

On the contrary, the master Nikolai appears to us in his main creations as an artist with a great decorative talent and, despite the obvious influence on him of the Byzantine designs, conveying forms is more fresh and truthful. They carved on the tympanum of the main portal of the Cathedral of Ferrara of St.. George, who kills the dragon, and on the tympanum of the portal of Verona Cathedral - Madonna on the throne between the images on the plots of the New Testament. Special attention should be paid here to vultures and winged lions, of which one, as in the vision of Ezekiel, is surrounded by wheels. But the figures of the paladins of Charlemagne, Roland and Olivier, on the sides of the entrance, are crudely executed.

Other masters who adorned the building with sculpture, kept to other directions. The sculptures in the Milan Archaeological Museum of Brera, which adorned the Porta Roman Gate in Milan, are extremely weakly technically executed by master Anselm, depicting the return of the Milanese to their city, rebuilt after 1162, in which it was destroyed by Frederick Barbarossa . These simple sculptures are endowed with a long inscription, in which Anselm is praised as a new Daedalus, a curious proof that ancient legends were still remembered in the Middle Ages.

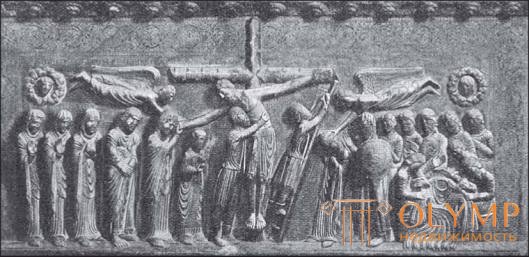

Fig. 147. Removal from the Cross. Relief of Benedetto Antelami in Parma Cathedral. With photos Alinari

The most significant sculptor of the epoch we are considering is undoubtedly Benedetto Antelami (ca. 1150 - ca. 1230), who graced the cathedral at the end of the XII century and the Baptistery he built in Parma with many sculptural works that are characterized by the freedom of form language, clarity of composition and the power of transmission of spiritual moods . Among the best of the early works by Antelami belongs in the cathedral relief in 1178 (part of the department), depicting the Removal from the Cross (Fig. 147). Baptistery sculptures executed between 1196 and 1216. The talent of Antelami in its highest degree of development is shown in the reliefs of the northern, western and southern portals of this building. On the northern doors, made in 1196, are depicted: in timpan - Adoration of the Magi, on the architrave - Baptism of the Lord, on the doorposts - the genealogical tree of Moses and Jesus Christ. On the western portal are placed: in tympanum - Christ the Judge of the world, on the architrave - the Resurrection of the dead, on the side pillars - Cases of mercy and Workers in the vineyard. Над южными дверями, косяки которых не имеют рельефных украшений, в тимпане воспроизведена одна древняя легенда: юноша, преследуемый единорогом, падает в пропасть, но, ухватившись во время падения за дерево, повис на нем; корни дерева гложут белые и черные мыши (день и ночь), тогда как на дне пропасти сторожит свою добычу дракон. По бокам рельефа изображены античные божества Гелиос и Селена. Тотчас бросается в глаза, что это изображение человеческой беспомощности над южным порталом находится в тесной связи с изображениями Искупления над северным и западным порталами. Множество глубоко обдуманных сопоставлений также в деталях составляет главное достоинство этих рельефов, исполнение которых, самостоятельное и понятное в том, что касается композиции, отличается неровностью и неуверенностью в технике изображения фигур. Последнее главное произведение Антелами — часть скульптурных украшений фасада собора в Борго-Сан-Доннино, близ Пармы. Величественны и полны внутренней жизни в особенности две фигуры натуральной величины, стоящие в нишах по сторонам портала: слева — Давид в царском венце, справа — пророк Иезекииль в желобчатом головном уборе.

О том, как велика была склонность Антелами подражать античному искусству, свидетельствует удивительная, близкая к классическому совершенству орнаментация на мотивы завитка, которую он пускал в дело повсюду в своих рельефах. Но новые веяния отражаются в его произведениях все-таки сильнее, чем античные традиции. Заимствовал ли он эту новизну, как полагали, из современной ему французской пластики, с которой нам предстоит познакомиться впоследствии, — мы не беремся утверждать. На одной и той же ступени развития искусства одинаковые условия часто приводили к одинаковым явлениям.

В первой, еще романской половине XIII столетия в верхнеитальянской пластике рядом с грубоватым местным направлением существовало направление, сознательно подражавшее античному и также кое-где византийскому искусству; это направление видно, например, в шести любопытных, сильно вытянутых женских фигурах в Ораторио-ди-Санта-Мария делла Валле в Чивидале, которые раньше считались произведениями средневизантийского искусства; напротив того, чисто средневековое направление выказывается в монументальном изваянии апостола Петра, сидящего на троне, в церкви Сан-Пьетро э Паоло в Болонье, с непреклонно-суровыми чертами лица, а также в исполненной хотя и жестко, но с большим реализмом серебряной золоченой курице с цыплятами, хранящейся в ризнице Монцского собора, — произведении, которое прежде считали лангобардским. Чистого художественного наслаждения эти произведения не могут доставить, но в художественно-историческом отношении все они весьма поучительны.

Consideration of the Italian miniature painting of this time we must provide a special study. Contour, wrong drawing is illuminated usually hard and sharp; bodily paint faces replace red spots.

In the overall picture of the Italian art of the mature Middle Ages, only a number of works of church architecture are essential and curious, with which their mosaic and sculptural decorations are inextricably linked. The Christian art of Italy only rarely quite consciously sought to descend from the ancient soil on which it stood in ancient Christian times and the early Middle Ages; besides, the influence of Middle Byzantine art, spreading to many areas of Italy and then growing stronger, then weakening, only in some cases allowed the sprouts of a new, independent life to develop in this country. The decaying Roman-Hellenistic ancient art (proto-Renaissance) and Middle-Byzantine art, as we have seen, were still predominantly in Italian

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)