At the time of the Roman emperors, wall painting was the main kind of painting . But we are better known for the wall paintings of Campania than for Rome itself, and even more famous are the paintings of Pompeian, samples of which were found in large numbers, described, published and researched in artistic and historical terms. The publication of the Kampania wall paintings began in the 18th century with the great inspiration of the Herculaneum Academy, which in the 19th century was followed, among other things, by the works of Tsan, Ternit, Raul-Rochet, Niccolini and Prezun. But the closest research of these numerous samples, which shed a bright light on the state of painting in the imperial era, we owe mainly to Gelbigu and Mau.

The excavations showed everywhere that at the beginning of the empire's time, the walls inside the buildings almost completely painted with bright colors on the plaster. As mentioned above, despite objections from other researchers, we, together with Donner von Richter, firmly hold the view that this painting was made mainly by wet lime, that is, a fresco, but was sometimes retouched by tempera.

Fig. 514. Portrait of Pacvius Procoul and his wife. Pompeian fresco. With photos Alinari

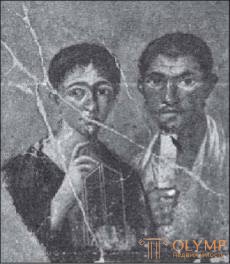

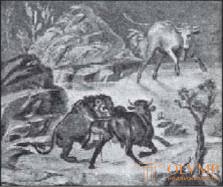

If we treat all this painting as a decorative component of architecture, our attention will be constantly riveted on a variety of architectural structures painted on the walls, either going deep or drawn on the same plane and components are still the main means of partitioning walls, large the luxury of a symmetrical or rhythmic alternation of the background of individual panels and an abundance of ornamental motifs adorning the walls. If, on the contrary, we begin to look at this painting with the eyes of the painter, then we will be equally impressed by the abundance of scenes with figures, landscapes and images of individual objects of inanimate nature scattered along the walls, as well as sometimes the diversity of the connection of such scenes through more or less architectonic wall decorations. The content of paintings with figures is the most diverse. True, the actual historical paintings are extremely rare. Herculaneum and Pompeian paintings with figures in most cases represent the Greek gods and heroes in the form in which poems depict them. There are also many paintings that idealize everyday life and which Gelbig calls the “Hellenistic genre” - love scenes, feasts, liturgical rites, musical and other entertainment. Women have fun with little gods, poets, musicians and actors - with their arts. Pictures taken from life depict without embellishment mainly the life of the working class, and their native origin is manifested in the artlessness of reproduction of scenes. These portraits are rare, but sometimes there are magnificent works of this kind, such as, for example, the portrait of Pacvius Procul and his wife, located in the Neapolitan Museum and amazing in its truth of life (Fig. 514). Landscapes are of every kind: large with mythological staffing or sacred trees, small paintings depicting only the foreground with several colors, and types of secluded rocky areas, animated only by wild beasts, and views of the coastal cities and villas of the artist Ludia. These pictures, having various sizes, abound in figures of people and gods, depict ships, mule drivers and the whole street and coastal life of the south; they either occupy entire walls, or imitate easel paintings inserted into frames, or they are scattered over a colored background in the form of individual adornments. Images from the lives of wild and domestic animals that inhabit the earth, air, and water turn into small, beautifully arranged groups of fruits, vegetables, and other food items, desk accessories, and a sacrificial altar. Human figures and inanimate objects are either among the well-defined environment around them, now against a monochrome background without any hint of the place in which they are located. The linear perspective in landscapes is usually approximately true, but never observed with scientific precision. In fig. 515 - one of the landscapes of the Neapolitan Museum in the form as it was written in reality, and as it should be corrected according to the laws of perspective. Where the clear sky spreads over the landscape, it is often fairly true that it is blue at the zenith, and at the horizon, depending on the time of day, it seems whitish, light yellow or reddish. Lighting, usually bright and cheerful, is evenly distributed. Shadows falling from objects are often strong and definite. They play an important role especially in landscapes depicting villas. But there is no mention of the transfer of other atmospheric effects other than lighting. The only “picture of the night” in the whole Kampania wall painting, the so often quoted image of a Trojan wooden horse kept in the Neapolitan Museum, would probably be less “night” in color, if it were possible to compare them with tones of walls and objects, who surrounded her.

Fig. 515. Campanian painting depicting the harbor: on the left - an exact picture from this landscape; on the right is his snapshot with a proper perspective correction.

As before, entire walls, especially garden halls and fences, were occupied with large landscapes. The imitations of framed easel paintings, usually with a specific landscape or architectural background, stand out sharply from the backgrounds of the wall panels in the center of the latter, and also appear to be no less obvious as if they were attached to or hung from architectural decorations painted on the walls. Among the architectural ornaments surrounding the panel, on the socles and cornices, are represented by separate figures of all kinds sitting or standing; the same figures are leaning against the columns and the doorposts or swinging on curls and garlands. On the very walls of the walls, instead of framed paintings, there are often depicted flying figures or groups of figures, giving the campaign wall painting a special charm. These winged or wingless mythological or fictional ideal figures, fluttering freely on the walls, are distinguished by graceful and easy, the impression of which is made by the Pompeian wall painting in general. In fig. 516 - a flying group of satire crowned with branches of Italian pine, and a bacchante with a tirs in hand - a wall painting found in Casa dei Dioscuri in Pompeii and kept in the Neapolitan Museum.

Fig. 516. Satyr and Bacchus. Pompeian fresco. From watercolor copy K. Otto

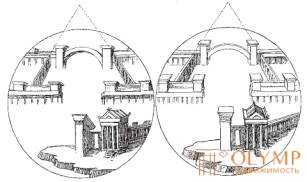

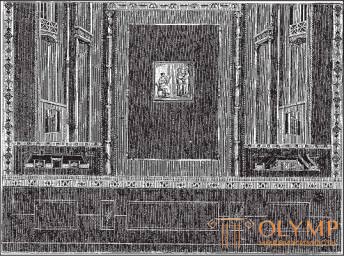

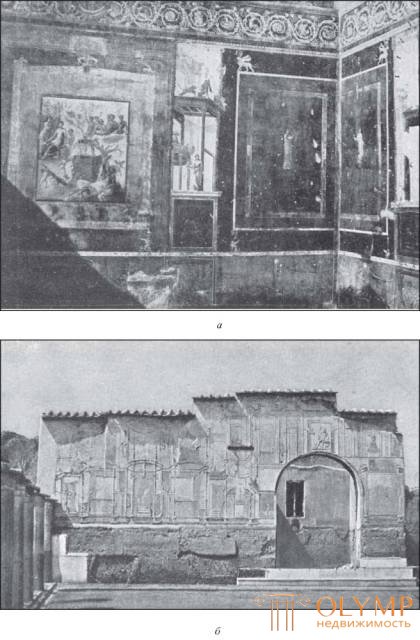

We have already traced the development of campaign wall painting almost to the time of Augustus. The extreme limit of this period of time is 79 AD. Oe., in which Herculaneum and Pompey died during the eruption of Vesuvius. Consequently, this period covers about 100 years, during which two styles prevailed. Around 50 AD e. replaced the old style was a new one. But it is impossible to draw a sharp line between the two. The third and fourth styles, as we call them from the time of Mau's research, did not occur one from the other and directly merge with the second, architectural style with which we are already familiar. The third attaches greater importance to the planar components of the second; in it the surfaces of the walls again come into their own; sometimes it turns columns and cornices straight into stripes and ribbons; neglecting the prospective removal and, in any case, limiting it, it increases the individual fields on the walls (Fig. 517). On the contrary, the fourth style develops the fantastic architectural elements of the second style even further. It does not deprive the drawings that divide the wall into the fields, their architectural nature, as the third style does, but replaces the architecture of the second style, although written only, however, in any case, possible, distinct, albeit bizarre, light and playful architecture.

Then the third style reveals a predilection for plant garlands of natural look and color, written on a light background, tightly connected and hanging, to flat ornaments on strips dividing the wall into fields, while the fourth style returns to the stylized second-style plant garlands, to their brilliant colors against a dark background, a combination with live figures (Fig. 518, a).

Fig. 517. Wall, made in the third style. From Casa del citarista in Pompeii. By Mau

Fig. 518. Walls, made in the fourth style, in Pompeii: (a ) the wall in the Casa del Sirico; b - a wall with stucco decorations in the Stabiae terms. From photos of Zommer

In the third style, preference is given to black paint for the base, red cinnabar for the main field and white paint for the upper parts of the walls, although sometimes there is also a purple base and blue or yellow, less often green, main fields. In the fourth style, the combination of yellow, red and black colors more often; in addition, a chord of two colors appears - yellow and sky blue; the purple paint disappears, and the red cinnabar gives way to brown or dark red. While in the third style the articulating stripes are white or whitish with purple, yellow and green ornamentation, in the fourth style the architectural ornaments are entirely bright yellow, which in this case is probably an imitation of gilding. The overall impression made by the walls of the third style is calm, cold and noble; Fourth-style walls are distinguished by greater warmth and elegance, but at the same time fantastic unnatural and playfulness of painting.

The oldest modification of the third style is given the name of the candelabra style, the hallmark of which is the dismemberment of the walls with the help of candelabra written in greenish tones, as, for example, in Casa dei capitelli figurati in Pompeii.

Among the third-style Pompeian houses, the main ones are Casa del citarista, the house of Cecilius Jukunda and the house of M. Spuria Mezor. But the great majority of the houses in Pompeii belong to the fourth style. The luxuriously ornamented wall in the courtyard of the Stabian Thermes in Pompeii (see Fig. 518, b) proves that in this style mosaics joined painting.

The third style came to Italy from Alexandria. This is evidenced by the Egyptian motifs in his scenery and the figures of the Egyptian character in his paintings. But that the fourth style was, as claimed, developed in Rome by the Italians and for Italy is unthinkable if we take into account the whole course of development of ancient art. Whether it comes from Alexandria or from Antioch in Syria, in any case, it should be looked upon as the last step of Hellenistic decorative art. Although in this style, the distribution of figures freely speaking among architectural motifs sometimes reminds of stage performances, it would be unreasonable to conclude from this, as some did, that the very origin of the style lies in the theatrical art. Be that as it may, the censure of Vitruvius, as can be judged by the era in which this writer lived, refers rather to works of a second style, such as those we see on the walls of the Farnese house than to the fourth style.

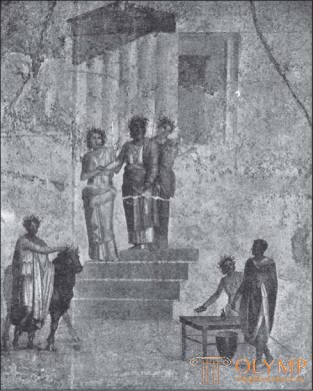

Our view on the development of the third and fourth style is confirmed by the review of the paintings related to them. In the third style, in the middle of the field, the walls are mostly depicted as a building like a chapel, and inside it is placed the main picture, mostly a large landscape with mythological stuff, with an uncomplicated scene of sacrifice or with sacred trees. The background of the main paintings on the themes from the Greek legends about gods and heroes was in most cases also landscapes or buildings, although they were often replaced by a simple white background. The figures, often scattered throughout the space without any connection between them, have a typically idealistic character, often represented in solemn poses, with Greek features, calculated movements, luxurious clothes, with the old, memorized arrangement of its folds. It is impossible not to notice their dependence on the archaic style of sculpture of a somewhat earlier and modern era, which was developed by the new atatistic school and the Pasitor school. Light, cold paints without sharp shades in yellow, violet, blue and green tones, to which occasionally bright red joins, contribute to the decorative and colorful impression of the walls; the subtle, fine reception of the execution of their painting is distinguished by thoroughness, but also by some dryness and dullness. By the works of this kind belong to the wall paintings in the Pompeian house of M. Epidius Sabin - "Release Hezioni by Hercules", "Hippolytus and Phaedra", "Diana and Acteon" and "Heracles and Muses" on a black background, supplied with Greek inscriptions. These are especially numerous paintings, separated from the walls and transferred to the Neapolitan Museum: "Iphigenia in Taurida" from the house of Cecilia Jukunda, two large paintings on a white background, "Heracles and Ness" and "Meleagr and Atlanta", from Casa del centauro, two paintings from one house, later opened, copies of which, the works of Gillieron, are in the Archaeological Museum in Halle, "Jason and Pelius" (fig. 519) and "Pan with nymphs". The characteristic mythological landscapes of the third style present us pictures on the four walls of the room, excavated in 1889: "The Fall of Icarus", "Pallas Athena and Marsyas", "Hercules in the Garden of the Hesperides" and "The Sacred Tree with the Sacrificers". The second of these paintings proves that in the Campanian wall painting two consecutive episodes of the same incident were sometimes depicted among the same landscape. The tendency of the third style to Egyptian forms and motifs is shown, for example, in the Egyptian figures of one of the rooms of the house of Vezoniya Prima.

Fig. 519. Jason and Pelias. Pompeian fresco. With photos Alinari

Most of all Pompeian paintings belong to the fourth style. The drawing in them is more bold and fresh, the classical severity of the faces gives way to a more spiritualized individual vitality, the nudity of the body is in its natural rights, the landscape receives secondary importance, but at the same time is more closely associated with the main figures; the colors become more rich and bright, the letter becomes softer and wider, and at the same time more plastic. The technique in which colorful stains and brush strokes are superimposed alone beside others without being extinguished to each other and merge together in the eyes of the viewer at some distance is less often observed in framed paintings on the main margins of walls than in architectural motifs, individual figures and decoratively sketched images inanimate nature, such as, for example, the groups of fish and game in Macellum. We have already seen a similar technique in the painting of the second style (see Fig. 486). The third style, because of its predilection for archaic rigor, neglected this method, the fourth used it incontinently, without refusing, however, completely from another method of writing, from the plastic modeling of the image. Both of these methods at the time of artistic maturity usually do not merge. Neither of them is superior to the other with regard to illusion; both of them seek to produce it, but using different means: one through the development of sculpture relief, the other through the shading of surfaces illuminated with light.

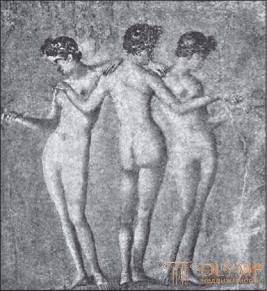

Among the mythological images, the ones found in Casa del Poeta tragico are particularly remarkable, namely "Sacrifice of Iphigenia", which we have already talked about (see fig. 335), "Admet and Alceste", "The Marriage of Zeus", "The Return of the Briseis" and " Check out the Chryseis "- paintings stored in the Neapolitan Museum. From the love affairs of the gods, the image of the judgment of Paris is often repeated. The Punishment of Eros and The Sale of Cupids, the Neapolitan Museum, and The Cupids Nest, Casa de poeta, are typical examples of a playful Hellenistic genre. The painting "The Three Graces", the Neapolitan Museum (Fig. 520), is a copy of a sculptural group that seduced Renaissance artists to imitate it and still finds copycats.

Fig. 520. Three Graces. Pompeian fresco. With photos Alinari

Very often the deities of light, Apollo and similar gods with him, but often other Olympians, such as, for example, Jupiter, on one of the Herculaneum paintings, are provided with a radiant crown or halo, which has been converted to Christian art as a symbol of holiness. However, it was not uncommon in the vase painting of the time of Alexander the Great, and we find it even in plastic design by Helios in the Hellenistic temple in Troy. Among the individual, as it were, flying figures and groups, the main role is played not only by winged images, which are the goddesses of victory, cupids and psychos, also satires and bacchantes, along with other, not always clear mythological female figures. Humorous pictures and caricatures, of which the images of pygmies in Egyptian taste were especially loved, were usually placed in rows in convenient places. Об изобилии изображавшихся сюжетов и об их распределении по стенам богатого римского дома можно получить понятие в самой Помпее при посещении дома Веттийцев, полностью сохранившегося.

Кем писана хотя бы одна из этих многочисленных картин серьезного и веселого, преимущественно же веселого, ласкающего взоры содержания, остается неизвестным. Это произведения безымянных комнатных живописцев; однако между ними легко различать работы мастеров неодинаковой силы, из которых лучшие, как, например, исполнитель "Сатира и вакханки" (см. рис. 516), были ремесленники первоклассные, близкие по своему искусству к настоящим художникам.

Бросив взгляд на фрески дома, соседнего с Фарнезской виллой, мы уже довели обзор стенной живописи Рима до времен императоров и перехода ее в стиль канделябров. Ко времени императора Августа относится еще несколько картин, стоящих вне вышеозначенного декоративного направления, каковы, например, жанровые и пейзажные эскизы в колумбарии виллы Памфили, легко и красиво набросанные на белом фоне; судя по беглости их исполнения, можно было думать, что они принадлежат позднейшим векам, пока Гюльсен, в своем дополнении к сочинению Земпера об этих картинах, не доказал, что они исполнены в самое первое время империи. В них, как и во всей римской гробничной живописи и живописи начальной поры христианства, дано по-старинному предпочтение перед другими фонами белому фону стен уже потому, что он, сильно отражая от себя свет, более удобен для живописи в сумрачных погребальных камерах.

Remains of a pure third style in Rome has not survived. But there is no doubt that the fourth style of Pompeii was distributed in Rome. Underground "grottoes" where, at the beginning of the 16th century, magnificent paintings of this genus were discovered, copied by Raphael and Udine and transferred to wall paintings of the highest Renaissance called "grotesque" (in Italian - la grottesca), remained in the ruins of the Golden House of Nero, were once taken for the terms of Titus. The photographs of these paintings and the remnants of these latter, with an admixture of stucco relief, prove that the Nero style of wall painting in Rome was not inferior to the fourth, Pompeian style in terms of fantastic pomp and originality, if not superior to it.

It is impossible to determine with accuracy how long the fourth style held in Rome. In any case, the plastered ceilings of two well-known tombs of the 2nd century AD. e. Via latina is still highly responsive to this style. One of them, the “white tomb”, contains only ceiling stucco reliefs depicting flying satyrs and bacchantes, newts and nereids (Fig. 521); on the vault of another tomb, small cheerful landscapes with surprisingly well-observed prospects alternate with reliefs on themes from Greek heroic legends. Perhaps the same time refers to the wall painting in Villa Negroni, known to us only from the drawings attached to the work of Butis, published in 1778.

Mau perfectly defined the nature of this painting. She has not completely drifted away from the fourth style; Thin wooden columns painted here still play an important role, but a return to the simplicity and truth of Hadrian's time painting is already noticeable everywhere. A full return to the second style can be seen in the frescoes of the dining room of a noble private house, described by Gulsen, opened in 1888, but unfortunately filled up again. Buildings with columns written here, differing in the correctness of the perspective, gave the room a more spacious look than it actually was and did not constitute anything implausible. At a broad stage in front of the depicted colonnade were slaves the size of nature, "ready to serve the invited guests" - the highest triumph of realistic vulgarity! The third century, as indicated by the inscriptions attached to them, also includes "the heroines of Thor-Marancho," in the Vatican library, female figures who once again try to express Hellenistic sentimentality, but which, imitating more sophisticated patterns, bring borrowed them the manner of performance to rudeness. After this time, apparently, the complete decline of wall painting began. The fact that it survived from the time of Septimius Severus testifies to its emptiness and nothingness. Later works of this branch of art prove that she has already returned to the field of crafts.

Fig. 521. The stucco finish of the white tomb on Via latina in Rome. From the photo

In antiquity, as we have already seen, a special kind of painting was used to decorate the floors - mosaic. In the twilight of the republic, the custom of making mosaic floors spread more and more. Apparently, then a new method of mosaic production appeared - opus sectile, the opposite of the so-called opus tesselatum. For works performed in this second method, small pieces of colored stones or colored glass were used, and the desired image was collected from them; in the first method, the image was composed of more or less large pieces of marble, carved with accuracy in the form of reproducible objects. Pompeian mosaics of this genus, prototypes of Florentine mosaics, can be seen in the Neapolitan Museum ("Satyr and the Bacchante"), and the prototype of the Roman - in the Palazzo Colonna in Rome ("Founding of Rome").

Fig. 522. Mosaic from Villa Adriana. From the photo

Among typesetting mosaics, Egyptian mosaics play a major role. This shows how great was the artistic influence that still emanated from Alexandria. The largest mosaic depicting the Nile is in the Palazzo Barberini in Palestrina. This is a colorful, lively Egyptian landscape, representing the sacred river at the time of its flood. The mosaics of the Villa Adriana, scattered throughout the various collections (in the Vatican, Capitoline, Berlin and other museums), are the best of those dating back to the times of the empire, consistent with the general character of the art of the Adrian era. From among these works, we already know Capitoline pigeons, reproduced from a well-known Hellenistic model (see Fig. 448). Also deserve the full attention of animal images, such as the Berlin mosaic, representing centaurs fighting wild animals, and the Vatican mosaic, which represents a lion attacking a bull (Fig. 522). The plots of such pictures seem to have memories of circus shows. The mosaic of the Lateran Museum, depicting the remains of dishes, shows its Hellenistic origin by the mere fact that the name of the artist Heraclitus is displayed on it. On the contrary, a rough mosaic image of athletes, originating from the term Caracalla and located in the Lateran, is a characteristic work of Roman art of the 3rd century BC. n e. The mosaic floors of the work of the Roman provincial masters introduced us already in an era of complete decline. In the imperial time there was no lack of mosaic decoration of the columns and walls, according to Alexandrian custom.

The middle part of the wall of the stage at the Skavra Theater in Rome, according to Pliny the Elder, which consisted of glass, was probably decorated with glass mosaics. Four round columns with images of hunting scenes against a blue background, located in the Neapolitan Museum, originate from Pompeii. In the Pompeii itself there are still several niches of fountains or nympheum, from the bottom to the top covered with mosaics. The works of this kind are very curious in technical terms, as the forerunners of the mosaic decoration of the apse in the first Christian churches.

Fig. 523. Portrait of a woman found on her mummy (I). From the photo of Brugsch

Examples of easel paintings of the era of the Roman Empire can be considered the Hellenistic portraits of mummies of Middle Egypt. A fair amount of works of this kind has long been in the Parisian collections and the Dresden collection of antiques. Thanks to the discoveries made in Fayum Graef, Kaufman, Petri and others, many large collections now own several specimens of such portraits, which are of the utmost importance because they are the only examples of ancient paintings on wooden boards and encaustic wax letters that have survived to our time. Donner's explanations regarding the technical execution of these works seem to us, despite the objections of other scientists, quite convincing. The portraits in question are mostly waist-length, without hands. With striking truth in life, they convey the individual traits of people of both sexes and of different ages, looking at us with wide eyes. In ancient times in Egypt, to reproduce the heads of mummies are usually resorted to plastic, and only in the Greek time such reproduction began to be replaced by portraits written on the boards. However, not all scholars admit, like Ebers, that some of these portraits date back to the Ptolemaic era. Without a doubt, most of them belong to the I and II centuries n. e., but, apparently, can be unmistakably considered their monuments widespread throughout the art of the Roman Empire. Egypt under Roman rule remained Hellenistic; portrait painting was also Hellenistic, the latest works of which are these boards. The best of them are notable for such breadth and power of modeling, such freshness and brilliance of colors and, at the same time, such expressiveness of depicted faces, which in the history of the European portrait we meet for the first time only in the XVII century. How much strength, severity and general character in the expression and posture of Mrs. Alina, in her portrait, located in the Berlin Museum and written, contrary to the custom, temperated on the canvas! What classical severity, with all the warmth of expression, is the distinctive features of a female portrait belonging to the Giza Museum (Fig. 523), and what a clear seal of individuality can be seen in the face of another female portrait kept in the same museum (Fig. 524)! In addition to these portraits, mention should be made of the portrait of a man with irregular, rough features found in the Copenhagen National Museum, and of portraits of a young European-style boy and an old lady with short gray-haired fake curls in the Munich Antiquary. Here not only the whole world of art, but also the whole world of life rises before us.

Fig. 524. Portrait of a woman found on her mummy (P). From the photo of Brugsch

From Egypt transferred to Rome as the art of decorating books with drawings. It has been repeatedly pointed out that this branch of art has spread throughout the world thanks to Hellenism. Only drawings in manuscripts (miniatures) of the later period of the ancient world were preserved. Since even the earliest of them belong only to the second half of the fourth century, consideration of them, strictly speaking, is already beyond the scope of this chapter. Nevertheless, from among these figures, the last generations of ancient art, we point out, firstly, the latest copies of 354 g. Of chronograph calendar published by Strigovsky and the Barberiniievsky library in Rome, published in the Vienna and Brussels libraries in Rome and, secondly, 58 drawings to the lost manuscript of the Iliad, stored in the Ambrosian Library in Milan and published by A. May, and 50 drawings in the Vatican incomplete list of Virgil (No. 3225).

In the drawings to the Iliad, we again notice the ineptitude of the transfer of individual forms and motives of movement. The episodes presented are often scattered over a vast background without interconnection. Images of Scamander are quite landscape. But if you compare, for example, the image of the underworld in this series with its image on one of the frescoes of the Odysseian landscape of the Vatican Museum, you will immediately notice how great the distance separating the intelligible language of the recent art of the Roman Republic from the artistic mumble of the era of the decline of the empire.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)