Hellenistic idealistic sculpture in Italy said, in essence, the last word in the works of the new atatistic school and the school of Passer. The only slogan of this branch of art was the imitation of the great masters of the past. The original works of the Greek cutter and Greek cast brought to Rome were distributed in a variety of copies, and sometimes, due to special requirements, there were deviations from the originals and their spiritual sense and artistic subtlety almost always disappeared. Many of these sculptures, in which we see the imitations of the masterpieces of the blooming pores of Greek art, are among the best works of this kind. The weakest are the ordinary antiques of our museums.

The best of the works of the era of Adrian were still full of the same life as the two centaur of dark gray marble, imbued with the work of Aristeas and Papias of Aphrodisias, which are in the Capitoline Museum. In other repetitions of these sculptures, small cupids are sitting on the backs of the centaurs; the senior centaur carries the god of love on himself as if against his will, and the younger one with joy and excitement. Of course, Aristeas and Papias were, if not the Hellenistic masters, who owned the originals of these sculptures, then the Greek copyists of Hellenistic works. But both of them were still good technicians, and for the time when they worked, the choice of their material was typical. Both in architecture and in sculpture, we increasingly find the use of colored varieties of marble instead of white with a full, albeit dimly colored. The main task of the sculpture under Adriana was the manufacture of an uncountable set of statues and busts of Antinous, with which she endowed all the artistic and religious institutions of the empire. As you know, Antinous was a handsome young man, a favorite of Adrian; To save his life, Antinous, driven by medical superstition, sacrificed himself for her and drowned himself in the Nile. The emperor expressed his gratitude to the deceased friend by assigning him to the host of gods and the command to render him the divine in honor throughout the empire. As a result, numerous preserved statues and busts of Antinous — a handsome young man with a broad chest, large, stern features, full lips, dreamy eyes, the Louvre (Fig. 525). Didrikson wrote about all these images taken together. In these statues and busts endowed with a melancholic expression and with all their individual vitality, they are not so much related to Roman portrait art as to idealistic Hellenistic, Anthina is either in the form of Bacchus, sometimes in the form of Hermes, then in the form of Apollo, and often even in Egyptian costume , in the form of Osiris. Of these images are famous colossal statue of Antinous in the form of Bacchus, in the Vatican Rotunda, and the bust of Antinous, in the same collection. One of the most beautiful busts of Antinous is located in the Louvre Museum, in Paris. We can also admire the noble features of a charming young man in the Neapolitan, British and Berlin museums and the Dresden Albertinum.

Fig. 525. Bust of Antinous. From the photo

The Romans have long been accustomed to considering Greek deities their own; therefore, alterations in the images of Greek deities according to the ideas of local Italian mythology were usually confined in Roman sculpture to attributes. Lanuvinsky Yunona Sospita, colossal and strict, stands in the Rotunda of the Vatican with a goat skin, thrown over his head and tied on his chest. The staircase of the Capitoline Museum is decorated with a cheerful and magnificent figure of Liber in leather and a wreath of grapes - a statue representing a female deity, paired with the ancient Italian god of wine Liber. Janus, Flora, Vertumn, Fortune - all these are Roman deities, whose artistic images are alterations of Greek types.

Attempts to further develop the sculpture of the Romans were expressed, on the one hand, in the personifications of nature, cities and nations, similar to those that were common in Greek art of the Hellenistic time, on the other hand, in images of foreign deities, the cult of which, after the Greek gods long ago merged with the Romans, spread among the Romans more and more.

Perhaps, of course, the Roman sculptor Coponius does not constitute a single phenomenon in it. He is credited with the statues of 14 nations, conquered by Pompey. But 12 figures of cities of Asia Minor on the base of the statue of Tiberius, dedicated to him in 20 AD e. these cities were undoubtedly of Greek work. The Puteolan Base of the Neapolitan Museum is an imitation of this basement. In written sources there are indications of similar Roman works of a larger size, and later incarnations of the same kind are often the only idealistic figures in Roman historical reliefs, which we will discuss below.

The introduction of foreign deities into the Greek Olympus and the transformation of foreign god personifications into Greek began in the Hellenistic East. Many-breasted Diana of Ephesus is preserved precisely in Roman sculpture. One of her statues, black and yellow, is in the Neapolitan Museum (fig. 526). Even Briaxis brought together in Alexandria Egyptian Serapis with the Greek god of the underworld, Pluto, and the supreme deity of the sky, Zeus. Statues of Serapis of this kind are often found in Roman museums. Subsequently, the favorite deity of Italy was the Egyptian Isis. The purely external imitation of the Egyptian forms, clothing and attributes in the Roman statues of Isis and her priestesses is somewhat theatrical, which, however, did not prevent these statues from appearing to the inhabitants of Italy as Egyptian; the same can be said about the images of Harpocrates, Anubis, Canopus and Syrian deities like Zeus-Baal and the "Great Mother" riding or sitting on a lion. Since the days of Domitian and Commodus, the Assyrian-Persian cult of Mifra has come to the fore, attributed to possession of a secret immortality. The sacrifice of the bull belonged to the main acts of this god, and therefore to the number of the main rites of his cult, and therefore the slaughter of the sacrificial bull Mifra, presented in the form of an Asian-clad young man, which usually takes place in a cave or in a vaulted grotto, has become one of the favorite themes of plastic images of times of decline art. Such sculptures are found in Roman museums quite often; in them, the poses and all the lines of the figures, even of the Victories that perform the sacrifice, resemble the balustrade of the temple in Athens, about which we spoke.

Fig. 526. Diana Efesskaya. Statue of colored marble

One of the best "Sacrifices of Mifra" is in the Lateran Museum in Rome.

Especially they are not uncommon among works of Roman provincial art, such as, for example, two reliefs stored in the collection of antiquities in Karlsruhe, one from Neuenheim, and the other from Osterburken.

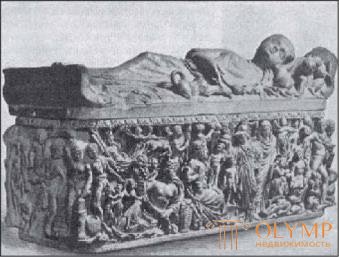

The latest efforts of the Hellenistic-Roman idealistic art were shown in embossed images on the marble sarcophagus of the empire. Despite the excellent work of F. Matz and the large, thorough study of Robert on the surviving sarcophagus, the history of their sculptural jewelry from the time of Alexander the Great to the era of Antonin, when the custom of burning corpses and storing urns with their ashes in columbariums, was again replaced by the burial of the dead in stone , "devouring the body" coffins, has not yet been composed. Nevertheless, we know that, both in the later and in the early times, sarcophagi made in Greek countries differed from those performed in Rome. The Greek sarcophagi, more than the Roman ones, remind by their form and gable cover of their origin from imitation of residential buildings; their embossed decorations are not so abundant and are located on all four sides, whereas the Roman sarcophagi, usually placed near the walls, are decorated with sculptural work only on the front and on two short sides, but in greater abundance. The sarcophagus in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, depicting the struggle of Hercules with a lion, Robert attributed to the times of the Roman Republic; on the contrary, the famous sarcophagus with the image of Hippolytus and Fedra, found in Thessaloniki and now in Constantinople, belongs to the later era of the empire.

In the real Roman sarcophagus of the time of Antonin, the lid becomes flatter, and sometimes, although in exceptional cases, turns into a featherbed, on which the half-sitting figure of the deceased is placed, as on ancient Etrore sarcophagi. An example of such sarcophagi can serve as the so-called tomb of Achilles in the Capitol Assembly, on the lid of which rests the couple of spouses. The walls of this sarcophagus are decorated with multi-figured reliefs, and in view of the twilight in which the sarcophagus was supposed to stand, the front figures were cut very distinctly and prominently. The content of reliefs, generally abundant figures, delivered mostly Greek mythology, but sometimes real life. Preference was given to the myths about Meleagr and Atlanta, Endymion and Selene, Eros and Psyche, Pluto and Proserpine; The legends of Niobids, Orestes, and the abduction of Leucipids also enjoyed love. Along with frequent reproductions of the Bacchus processions, solemn processions of sea deities were depicted. Along with the battles of giants and Amazons, inherited from ancient art, there were depicted battles with barbarians, the events of the relatively recent past. Sometimes the choice of plot symbolically hints at the secret of life and death. This is most clearly seen on the Prometheus sarcophagus in the Capitoline Museum (Fig. 527): Pallas Athena is depicted, giving Prometheus a human soul in the form of a butterfly, then flying away from the deceased in the same form. But free-fictional stories are almost never found. In most of the motifs, their Hellenistic origin is striking. Probably, there were special warehouses of pictorial and plastic originals, open for general use to sarcophagus manufacturers. The language of the forms in these latter, at first pure and strong, quickly faded and ran wild. Finally, even the groove, carved for the body of the deceased, was left hewn somehow. Art again condescended to the degree of craft. All the more surprising is the long existence of the need to decorate even the coffins of the dead with the ghost of artistic luxury.

Fig. 527. Prometheus sarcophagus. With photos Alinari

Roman portrait and triumphal reliefs introduce us to a completely different world. Bernoulli wrote about the first of these branches of sculpture, and Filippi and Courbot about the second. In the field of portrait sculpture and historical relief sculpture dominated the Roman spirit and the Roman sense. It was necessary to accurately depict the personalities of the new masters of the world and glorify their great deeds in Rome itself and in the extreme limits of the universe. This truly Roman imperial art was realistic in the full sense of the word, and it was precisely because it was realistic art, though it was sometimes considered necessary to throw a cloak of idealism on itself or return to idealized nudity and depicted events and faces of its time. descendants of historical art in a closer sense of the word than the one that in a long time ago produced invented images of this kind.

When Augustus in the Roman portrait sculpture and the triumphal relief was dominated by deliberate restraint in the spirit of the newly revived ancient Greek traditions; in the period from Titus to Traian, these branches of art used their own, more fresh and bold techniques; under Adriana, there was a short return to antiquity, the revival of the Greek trend in Roman art. After Adrian, the decline was irrepressible. Under Constantine, the antique creative force finally disappeared in this area.

The task of the Roman portrait sculpture was initially an image of individuals. The best works of her were busts, statues up to their full height and sitting figures of Roman citizens, their wives and daughters, and in these works we find, as noted above, character and real, genuine vitality, caught up with such direct observation of reality, which is not manifests itself even in the Hellenistic portrait busts, despite their individual character. Roman portrait painter turned its attention mainly to the most essential features of the head; everything else was usually formed according to more or less established general rules, and in some cases even prepared in advance, in reserve. Of the female statues found in Herculaneum and stored in Dresden Albertinum, the oldest represents a woman with a beautiful head, full of individual life, while the two statues of a later time have several ordinary features. The clothes on them and the location of its folds are Greek. The two equestrian statues of the family of Balba, in the Neapolitan Museum, originating from Herculaneum, we see already perfectly sculptured, intelligent, lively Roman heads. Amazing naturalness, combined with Greek rigor and grandeur, breathes the facial features of the Vestalka Museum of Therm, dating back to the era of Trajan (Fig. 528). Among the busts of the early times of the empire, the bust of Clytia, in the British Museum, is especially remarkable - a graceful, chaste female image, as if growing out of a calyx of a flower.

Fig. 528. Vestalka. Marble statue. From the photo of Anderson

Roman portrait sculpture then turned into imperial art in the full sense of the word. Statues to their full height and in a sitting position, the busts and heads of Roman emperors and members of their families, male and female, are important both as historical documents and as monuments, testifying first of the course of development, and then of the decline of art during the time of the empire. The spiritual greatness of the noble emperors is expressed in their heads with the same clarity as the moral nothingness in the heads of the Caesars, who were the scourges of humanity. At the same time, it doesn’t matter how the emperor would have been depicted: in a peaceful toga, as chairman of the senate, whether in a mantle thrown over the head, as a high priest, fully armed, as a military leader, or naked, in the form of a god or a hero.

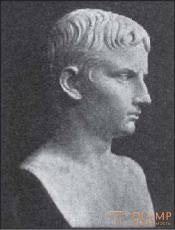

Fig. 529. August in his youth. Marble bust. From the photo

Look at the head of the young Augustus, stored in the Vatican (Fig. 529). Is there anything better, more truthful and noble than she in the field of portrait sculpture? Then look at the famous statue of an already aged Augustus, found in Prima Porta and also exhibited in the Vatican Museum (Fig. 530). Clothed Augustus speaks to his troops; his right hand is raised up with an oratorical gesture; the shell is decorated with a Hellenistic relief, depicting heaven and earth and the rule of the Romans over the whole world in majestic avatars; the emperor's lips are closed, although words seem to run out of them, and all the features of his face are eloquent. The inner life is here expressed mainly in the head. Cupid riding a dolphin at the feet of Augustus alludes to Aphrodite, the ancestor of the house Julius. The Capitoline Museum owns a beautiful statue of a seated woman, who is considered the granddaughter of Augustus Agrippina the Elder (fig. 531). The motif of the seated draped statue and here the Hellenistic, but intelligent, lively face is completely Roman. In the Louvre is a good bust of Tiberius in an oak wreath; whether the bust of the Capitoline Museum really depicts Caligula is questionable. Famous colossal statue of the Lateran Museum, depicting Claudius sitting on a throne in the pose of Zeus. Driven by self-love, Nero erected a bronze statue of himself in front of his Golden House, larger than the size of the Colossus of Rhodes. The performer of this work, to which Pliny the Elder indicated as an example of the decline of the casting technique, is considered to be Zenodor, obviously again a Greek. In the busts of Nero, executed some time later, a short beard appears, as, for example, at the bronze head in the Vatican library. In general, the custom to shave smoothly existed before the era of Hadrian. This emperor again brought into fashion a short, bulky beard, as in ancient Greece. On the busts of the empresses one can trace the changes that occurred in the hairstyles. The wife of Adrian Sabin, in the Capitoline Museum, in the words of Gelbig, "is a sample of the bravura marble technique" of the times of the sovereign named. The heads of Marcus Aurelius, good as portraits, are already artistically weaker. The bronze equestrian statue of this emperor, standing on the Capitol and so often mentioned in the writings, despite its flaws, 1300 years after its manufacture, served as a role model. In the III. types of emperors are becoming increasingly barbaric, and reproducing them more carelessly, although the busts of the “Satan” Caracalla (died in 217) are still full of amazing life. The onset of medieval numbness already makes itself felt in the colossal head located in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, in Rome, which we, together with Eugene Petersen, consider the head of Constantine the Great.

Fig. 530. Commander Augustus. Marble statue. From the photo

The transition from portrait sculpture to triumphal reliefs consists of images of barbarians. The head of a young German, in the British Museum, the head of a young German, in the St. Petersburg Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, three colossal Dacian heads, in the Vatican, are typical examples of works of this kind.

A series of triumphal reliefs from the time of the Roman Empire begins with the Altar of the World, adorned with "ara pacis Augustae", erected in 13 BC. e. By the Senate in honor of Augustus on the Field of Mars and consecrated in 9 BC. e. The recognition of his wreckage, scattered across various collections (Palazzo Fialo, Villa Medici and the Vatican in Rome, the Uffizi in Florence, the Louvre in Paris), is merit Fr. von Dun, but we got the exact concept of this altar thanks to Eugene Petersen. The outer surface of the circumferential wall of the altar, bounded by pilasters, was divided by a horizontal stripe, decorated with a very elegant meander, into two tiers: the lower tier was occupied by an extremely luxurious garland of acantha with stylized flowers jutting out of it; in the upper tier, on both sides of the entrance gate, a bull sacrifice was depicted; in the middle of the back side was the famous relief of the three elements (now in the Florence Uffizi Gallery), long regarded as a model of the Hellenistic anthropomorphic image of nature; a solemn procession in which the emperor's family participates, leaving this picture, headed on both other sides of the wall to the sacrifice presented at the entrance gate. The style of these reliefs is twofold (high relief and bas-relief), but still strict and noble; faces of the depicted figures are distinguished by subtle portrait likeness. In general, this monument, belonging to decorativeness, obviously, to the second style of Pompeian wall painting, gives a good idea of the purity and freshness of art forms in the August century.

Fig. 531. Agrippina the Elder. Marble statue. From the photo

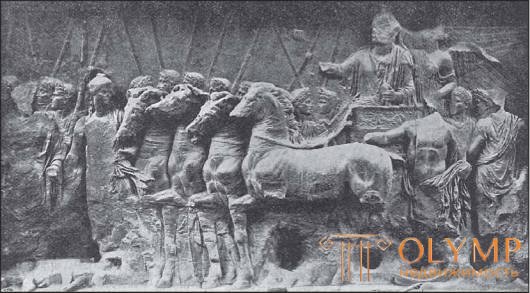

In the three large reliefs depicting groups of warriors who once adorned the Claudius arch, and now in Villa Borghese, near Rome, foreground figures come forward even more than such figures on the Altar of the World. Further development of the relief in the Roman spirit we see in the sculptures of the arch of Titus. Two main images on it relating to the triumph of Titus after the destruction of Jerusalem adorn the walls under the arch of the span. On one side is the emperor himself, riding, accompanied by a retinue on a winning chariot drawn by four horses, led by Roma by the bridle (Fig. 532). On the other side there is a triumphal procession, in which utensils, by the way, a silver candlestick, are seized in the temple of Jehovah. The development of style is manifested in these images mainly by a greater depth of space, achieved through the use of three picture planes of relief instead of two; a fresh sense of reality emanates from the whole crowd of noble, bold light figures in their movements, the vitality of which was once enhanced by coloring and gilding.

Fig. 532. One of the reliefs of the triumphal arch of Titus in Rome. From the photo

The times of Trajan belong to the forum fences, opened in 1873 and then restored. On their inner side are the so-called Suovetaurilla, a sheep, a pig, and a bull — the animals of the great Roman state sacrifices. On the outside are the various acts of Trajan as the benefactor of the Romans. The style of these reliefs is even closer to the picturesque. All constructions of the background of the forum are reproduced here by flat relief.

Arch of Trajan in Rome destroyed. Her workshops reliefs, of which 8 charming round images glorifying the life of this emperor, were later transferred to the Arch of Constantine, represent a highly attractive combination of realistic power with a sense of style inherited from the preceding time.

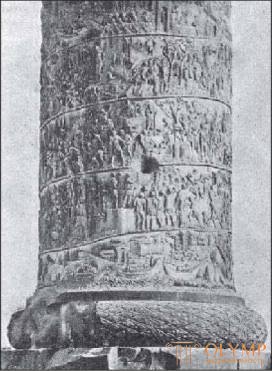

As for the column of Trajan, it still stands in its place (Fig. 533). Reliefs wrapping around her like a marble spiral tape that makes 23 full turns on it depict episodes from the emperor's victorious wars with dacians. Individual figures in these reliefs, reaching a height of 75 centimeters, there are more than 2500.

Two campaigns against the Dacians and their final defeat are depicted with all their details, strongly, real and vividly. A quick change from one scene to another excites the viewer, as E. Petersen says, "an increasing interest." In conclusion, Decebal, the leader of the vanquished, pursued by the Romans, "falls under an oak tree, cutting his throat with a curved sword." Thus, we see that the Romans in these images have reached the real historical art. Although it is noticeable in the implementation of reliefs that different masters worked on them, some of which, at the bottom of the belt, obviously intentionally made them flatter, and others, at the top, more convex, but all this sculptural work as a whole has the same character.

Fig. 533. Part of the column of Trajan in Rome. From the photo

Reliefs from monuments in honor of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius are preserved in the Palazzo dei Conservatory. The eight plates with images of the state actions of the emperor, located on the long sides of the attic of the Arch of Constantine, refer, as Petersen proved, also to the time of Marcus Aurelius. The large relief wrapped around a column of Marcus Aurelius is nothing more than an imitation of a model that was 60 years earlier than it. This spiral relief makes 21 turns around the column and presents episodes from the emperor's campaign against the Marcomanni. New original features are found here only in some places. Even the intervention of Jupiter, Pluvius, who is anthropomorphically expressing the power of nature and giving the Romans coolness with streams of rain, and barbarian fearsome hail, was previously depicted in the same vein. The nature of the relief is less plastic; the figures, instead of being placed one behind the other, are depicted standing side by side; secondary landscape details often disrupt the coherence of the location. In all this it is impossible not to see the weakening of artistic power.

Following the pattern of these reliefs, the sculptural ornaments of the arch of the North, erected in 201 AD, are executed. e. to commemorate the victory of the emperor over the Parthians. Not a single arch abounded so much with reliefs as this one, but no other reliefs testify to the same extent as they, about the decline of plastic feeling. In the composition of the processions depicted here, stretching over vast spaces, the arrangement of the figures one next to the other, sometimes representing four or five kinks, completely supersedes the promising placement of them one after another. You might think that before us is the Assyrian relief of a later style. At the same time, the language of forms in certain parts is gross and incorrect.

The best evidence of the extreme impoverishment of creativity at this time may be the fact that when in the 4th c. built the triumphal arch of Constantine the Great, then for its decoration it was necessary to trim the arch of Trajan and other monuments. The works of the very same era of Constantine are so different in their poverty of fiction and inability to own form and express themselves artistically that they clearly show the final fall of ancient art. One had to go after a thousand and a hundred years before the posterity of the Romans was able to reconnect their art with the best examples of the ancient.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)