In the vast field of beauty of applied art, which includes countless utensils, jewelry and jewelry items - works of small size, but truly artistic, the laws of architecture, sculpture, painting individually or all these branches of art dominated, and However, it naturally entered into its own rights and ornamentation. The surviving art and craft products from the time of the Roman Empire are made primarily of stone, clay, bronze or precious metals. Wood products did not survive; from the tissues, with the exception of Egyptian, only scant remnants have reached us. Decorations of art products are now more often embossed than flat. Ceramics for its decoration has long ceased to resort to painting, which was widely used in Greece and in early Hellenistic Italy, and began to use half-raised ornamentation. Clay lamps, preserved in an uncountable number, with regard to the expediency of their form and the meaningfulness of the decorations, can be put on the same level with other earthen vessels.

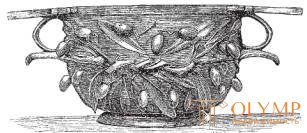

Fig. 534. Bowl from Boscoreale. According to Engelman

The most important are gold and jewelry. We have already talked about silver items found in Pompeii, Boscoreale, Hildesheim and other places, mostly as Hellenistic works (see fig. 434 and 435). Roman items are very different from them in Latin inscriptions of masters and often more luxurious decorations, which, however, are sometimes less consistent with the shape of the objects themselves. If the magnificent Hildesheim silver crater of the Berlin Museum with a stylized garland animated by figures of Amurchik and sea animals agrees with our idea of Hellenistic art, then vases completely entwined with realistic branches, such as, for example, the Pompeii vessel with vine branches stored in the Neapolitan museum, and a wonderful vessel from Boscoreale with olive branches, located in the Louvre Museum (Fig. 534), closer to our concept of the nature of the ornaments before the beginning of the era of empire .

In the case of cameos, it is easier to establish a border because the images on them glorify the Roman emperors; but the splendid cameos of the first times of the empire, such as, for example, the famous "August Gemma" of the Vienna Antique Cabinet, the Gemma Tiberiana of the Parisian National Collection and the Gemma Claudiana of the Hague Cabinet, which are distinguished by a good general style and subtlety of work, cannot be compared with the Ptolemaus cameos (see Fig. 434 ). The same should be said about the coins of the times of the empire. A real Roman is a copper coin as with images of the head of a two-faced Janus on one side and a ship’s nose on the other. Roman imperial coins, which at the beginning of the empire, as in the epoch of Hadrian, had a Greek character, remained all the time only bad repetitions of Greek samples, and after Hadrian and in this branch of art began a rapid decline.

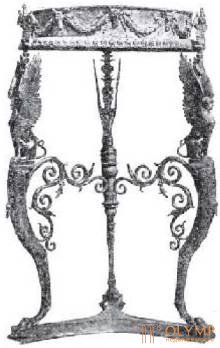

Fig. 535. Roman marble candelabrum. With photos Alinari

Among the utensils elegant in form and artistically decorated utensils that have come down to our time, the main place is occupied by marble and bronze products. The collections of Rome and Naples are especially rich in tables, armchairs, tripods, lamp stands, footings and magnificent vessels of white and colored marble. The ornamentation of these items becomes increasingly luxurious over time. The legs of tables and tripods are usually in the form of strong, resilient lion's paws. The upper end of the table leg, the transition to which from the bottom is masked by the ornament of a stylized acanthic motif, is sometimes made in the form of a lion's head supporting the table board. The legs of the table are also sitting sphinxes. In addition to the tripod marble table from Pompeii, located in the Neapolitan Museum, you should point out the beautiful tables, legs or wider lower parts of which, covered with luxurious ornaments, are preserved near the ponds of Pompeii atriums, for example, in the house of Cornelius Ruff. After the Latin candelabrum with a quadrilateral base and a spiral fust decorated with separately planted acanthus leaves, a pair of Vatican candelabra with a triangular base densely decorated with lush acantha leaves are worthy of note (Fig. 535).

Fig. 536. Pompeian bronze tripod. From a photo of Zommer

In general, the artists of East Asia alone were able, to the same extent as the Greeks and Romans, to add utensils and dishes to an elegant and at the same time expedient basic shape and to decorate them meaningfully, with resourceful ingenuity and taste. Unfortunately, from what has been created by the most excellent of this kind, very little has survived, except for earthen vessels.

Fig. 537. Part of the frieze and the eaves of the Temple of Vespasian in Rome. By petersen

In conclusion, let us once again return to the history of the development of Roman ornamentation in its entirety. Along with the meander, wavy ribbon, braided line, Doric and Lesbian stripes, pearl cord and dentils, with rosettes originating in the East, palmettic ilothos friezes inherited leaves and stems from Hellenic art. Acanthus and other sheets, copied from life, were transferred to Roman ornamentation also from Greek. They were joined by figures of animals and people, as well as stylized flowers of various kinds. In the Hellenistic era, plexuses of fruits and flowers were shaped as garlands hanging from bull skulls and sometimes decorated with ribbons. During the time of the empire, all these motifs were not only retained, applied and combined, but also developed further. The simple geometric forms of the good old days were more and more out of use. Plant wreaths, leaves, and antennae of plants received more and more soft, luxurious, and natural forms; they are now more often than before, completely covered the entire surface. But next to them, such items as vases, tools, trophies and waving ribbons found use in ornamentation; in some places, new schematism was introduced into the floral ornament, indicating a return to geometric shapes.

The combination of architectural elements inherited from antiquity is striking when looking at fragments of friezes and main eaves of the newly built Tiberius Temple of Concordia and the Temple of Vespasian (fig. 537); these fragments are stored in Tabularium, in Rome. Among the most magnificent monuments of this genus is the frame of the “rich door” in Balbeck, on which at least one of the ornamental motifs bequeathed by history is hardly missed. On the frieze of Agrippa's term are dolphins, tridents and shells between palmettes; on the frieze of the temple of Vespasian, we already see the sacrificial utensils, rods, axes and knives - new decorative motifs that appear with bull skulls and rosettes. Stylishly heaped trophies are found on some of the capitals; we find them also at the quadrangular foot of the column of Trajan. As the whole surfaces were filled with floral ornaments, you can see not only on the vases, but also on the lower part of the walls of the Altar of the World of Augustus. Further development of this type of ornament is a magnificent relief of the branches of quince and lemon tree, stored in the Lateran Museum in Rome.

Fig. 538. Frieze with vegetal curls in the forms of acantha

A. Rigl studied the development of stylized plant leaves and antennae, and Fr. Vikgoff perfectly outlined the success of the use in the ornament of natural forms of plant branches. As the desire for stylization receded into the background, the naturalistic direction came forward. In the stylized ornamentation, the ancient motifs of the plant tendrils alternating with the palmette, gradually more and more approached the form of the acanthus. Its leaves more and more often encircle the mustache, and above all appear among the palmettes or stylized lotus flowers, until finally they are completely crowded out. The two remaining Nerves of the Frieze represent the final point of this movement, which, despite the seeming progress in relation to naturalism, but actually only an elusive one due to the unnatural acantha motives, was nothing more than a return to the shackles of schematism. To verify this, just look at the fragment of the frieze located in the Lateran Museum (Fig. 538).

Naturalistic vegetative ornamentation, like figure relief, developed further in the spirit of painting. The branch of the plane tree in one famous relief in the Terme Museum, Rome, is plastically treated in kind, but the above-mentioned embossed branches of the quince and lemon tree in the Lateran Museum go on picturesquely further, since they take into account the effect of light and shadows. . Precious pilasters of the Tomb of the Gaterians, in the Lateran Museum (Fig. 539) are characteristic of this area. High vases entwined with roses, on the upper edge of which the birds sit, rise above the cherry branches surrounding their base. Here not every leaf, not every flower is copied straight from nature, but the stems, leaves, buds and flowers protrude above the background to different heights and with the play of their original colors, glare and shadows, they must have the impression of a complete similarity of nature. In this work of II. n e. Roman art follows a path that has already deviated far from the paths of ancient Greek art. But another pilaster of the Lateran Museum, covered with brushes and foliage of grapes, is already a reverse flow, closing the relief to the limits that the height of the highest of its planes takes to it.

Fig. 539. Pilaster gravestone of the Gaterians. According to vikgoff

As Greek art, the beautiful product of the northern wonderland, penetrated with Alexander the Great into the hot countries of Hindustan, so Hellenistic-Roman art followed the imperial legions into the most distant provinces, where the Roman eagles did not enter. At the same time, Roman architecture kept the borders of the empire itself, and everywhere on its borders, as we have already seen in a sufficient number of examples, was slightly subject to the influence of the neighboring arts. In the Far East, it partly assumed the character of eastern pomp, on the hot southern borders of the empire it was revived by the trend of free African steppes. Works of Roman architecture on the Rhine, on the Moselle, and in France reflected the Gallic and Germanic strength and severity. In our place, we will see how, under Hellenistic-Roman influence, all other branches of art developed among the northern barbarians and turned to Roman provincial art, as all Hellenistic-Roman art took root far beyond the eastern borders of the empire among Parthians, Sassanids and Indosciphes and gave new foreign roots, extending its influence even to India and China. In no part of the Old World did the “legacy of antiquity” disappear completely, but the people of Europe were called upon to join this heritage; even in the darkest time of the Middle Ages, their connection with this heritage did not completely disappear. The fact that the Greeks discovered and felt in the field of art, while they retained their nationality, something that itself adapted to the new needs of life during their internationalism, all that the Romans went through in this respect and smashed it with their legions to the world - all this continued to sound loudly and clearly among the sea of foreign tones that proclaimed the centuries that followed the migration of peoples, and then, when it came to that time, it all broke out again with elemental force, in all the power of light, and Tina and beauty back many centuries got the leading role in the art of mankind.

After the Gothic Middle Ages, which, perhaps unknowingly and unwillingly, showed the greatest estrangement from antiques, but were nevertheless animated by an independent great sense of style, only in recent times there have been isolated attempts, and, moreover, attempts for the first time quite conscious, completely free from the influence of classical traditions; but time will show to what degree this movement is firmly in place and whether it has the power to create forms that could measure themselves with their original artistry, vitality and natural sense of style with what was created by the Greeks and Romans

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)