The Persians, who in the ancient times of the Achaemenids and Sassanids had their own rich art, although it developed, strictly speaking, under foreign influences, in the epoch of its accession to Islam in some respect were at the head of the artistic movement that took place among the peoples who adopted this religion. Of course, it is not easy to determine how much they gave to the Arabs at first, and how much they borrowed from the Arabs later, when they created their own language of artistic forms from foreign elements. But there is no doubt that the Persians, several centuries after the Arabs conquered them, had already taken an active part in the general development of Muslim art, although they retained in it some of their special features; no doubt also that after the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols, they perceived and reworked Chinese influence.

In the era of the Abbasid caliphs, the capital of Persia could be Baghdad, although it lay, like Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sassanids, on the Tigris. However, neither Baghdad nor other more eastern cities of Persia have survived any significant art monuments in the early days of Mohammedanism in this country. Only on the basis of ancient descriptions we can, together with Al. Gaye, who published a general overview of the history of Persian art, assumed that the ancient Persian mosques differed from the Arab and Egyptian first centuries of Islam only in that they had a dome over the middle of the sacred space. The ruins of two tombstones in Rai, ancient Ragesa, near the current capital, Tehran, ascribed as early as the 8th century, allow us to conclude that these tall cylindrical buildings with a pointed arch in the entrance portals ended at the top with domes also of a pointed shape. The outer walls of one of these towers are smooth, the other is ribbed in a vertical direction.

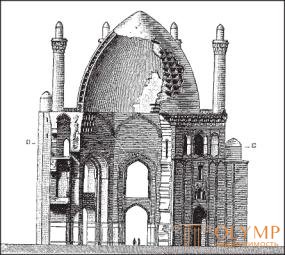

Fig. 657. Section of the tomb of Khodabende Khan. By delafua

The peculiarity of Persian art, with its further development, which we can trace only from the time of the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols under the leadership of Genghis Khan (about 1200), are wide keel-shaped arches corresponding to their bulb-shaped dome shape, and massive, taken from the Sassanids, the vorog, whose entrance arch, forming a deep niche, is usually bordered with a rectangular fake frame, and also round, smooth minarets, with only one covered gallery at the top, under the dome that crowns them. Persian art is generally softer and more sensual than Arabic-Egyptian and Moorish art. Mathematical, intertwining polygonal patterns are almost completely absent in developed Persian art. It is dominated by arabesques in the form of twisting antennae, but what is especially remarkable is the fact that it is not at all stopping by images of living beings, people and animals. The existence of Persian sculpture and Persian painting cannot be denied; at least, Persian miniatures constitute a special branch of art that cannot be silenced when considering its history. Moreover, faience of every kind, which played an important role in the architecture and production of vessels, as well as carpets, which Europe has been admiring since the 15th century, deserve to be mentioned as the main artistic and industrial works of Persia.

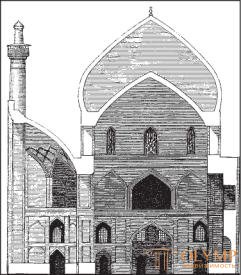

As the most important monuments of the XIV-XVI century Persian architecture, you can point to the tomb of Khodabende-Khan in Soltaniye, built in 1313 (fig. 657), an octagonal building in plan, richly decorated inside and outside with a mosaic made of white, blue and blue brick, with a dome, with an arrow gallery under the dome and high slender minarets in the corners; then, to the Blue Mosque in Tabriz, built in 1478. According to its plan, devoid of courtyard, and the large central dome, it resembles Byzantine designs, while its in-depth entrance gate with its half-dome, decorated with stalactites, has a purely Persian character, and the mosaic of shiny plates covering it outside and inside with its pattern on a cobalt-blue background strongly resembles strictly Arabic patterns. This mosque, as if it did not belong to the Sunni sense prevailing in Persia, is now in ruins. Samples of its mosaic decorations are available in the Sevres Ceramic Museum and the Berlin Art and Industry Museum. Patterns interlaced with written characters represent, as Sarah said, "turquoise-blue, white and yellow, which were originally gilded figures on a dark blue background."

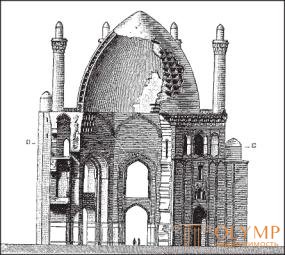

The era of the Renaissance of Persian art, the works of which are best known to us, is considered to be the 16th and 17th centuries. These were the times of the Safavid dynasty, of which Shah Abbas I, nicknamed the Great (1587-1629), particularly patronized all branches of art. True, the time of the great Persian poets was long gone: Ferdowsi wrote his heroic poem as early as the 10th century, Saadi composed his books full of wisdom as early as the 13th century, Hafiz composed his immortal songs back in the 14th century; the generations following them were engaged in poetic creativity in Isfahan, the new capital of Persia. Perhaps, also in the field of figurative arts during this epoch of the Persian Renaissance, the XVI and XVII centuries, we would see only the late flowering, if we were well acquainted with the artistic works of the preceding centuries. Be that as it may, under the Sefevids we find a flourishing, multifaceted artistic life in Persia. As one of the most magnificent creations of Persian art, you can point to the Safi tombstone in Ardebil, explored by Sarah. In its magnificent tiled-mosaic decorations, finished by Shah Abbas, next to the floral patterns in a new way in some places there are almost Chinese motifs. The capital of Shah Abbas was Isfahan, a city whose layout was a work of art. His royal palace, educational institutions and mosques were surrounded by flowering gardens; its caravanserais, trading rows and rich houses stood in regular rows, forming straight streets and spacious squares; a large shah square, a rectangle with a length of 386 and a width of 140 meters, is surrounded on all sides by two-story arcade galleries. In the middle of each of its sides is issued on the portal, of which the south is the threshold of the Great Shah Mosque, one of the best architectural monuments of the Persian Renaissance. This mosque was built according to the old plan. The middle of it is an open courtyard with a fountain; on each side of the courtyard there is a purely Persian portal; the main portal of the western side leads to a luxurious prayer hall, topped with a high dome (Fig. 658). Double dome: above the low and simple internal dome, another, external, more daring and high, dominating the whole building, is arranged. The dome is raised above the roof with a tambour. And this mosque is decorated inside and outside with faience tiles, and here the tin-glazed tile presents to us on a white background the same luxurious purely Persian ornaments, consisting of stylized vegetable twigs and tendrils, into which a special character has a long, toothed, feathery sheet and a peculiar flower , called by us and Rigl the Persian palmette, since in its form it most closely resembles the ancient palmette. In these patterns, the ovoid nucleus is crowned with a tuft and surrounded by a crown of straight leaves. However, here, as in the Turkish ornamentation of the same time, sometimes there are slightly stylized natural flowers, the breed of which is easy to recognize.

Fig. 658. Section of the Grand Shah Mosque in Isfahan. According to Gaia

In the history of ceramics, Persian faience plays an important role. All the above-mentioned (see fig. 643-646) four kinds of faience - real faience with opaque tin glaze, faience with metallic luster, semi-faience painted under a transparent glaze, and faience mosaic - common in Persian technical production, if not encountered its soil. The early history of the Persian faience was shed by a bright light, predominantly of Henry Wales research, produced in private collections in New York and London, as well as in London museums.

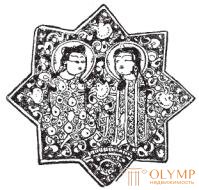

The oldest tile found in Persia plays a golden sheen against an ivory background. It has the shape of eight-pointed stars, alternating with crosses, the ends of which are equal in size, sharpened.

Fig. 659. Ancient Persian tile with a golden sheen. According to wales

The decorations on them consist partly of Persian arabesques, partly of figures of animals and people, in which Chinese influence is already noticeable. We see this, for example, in the 1217 tile, which in 1893 was in the private collection of Mr. Alfred Gigins in London. The spotted hares depicted in the middle are copied from Chinese samples. The same can be said about the tile, which is stored in the British and South Kensington museums. The human figures represented on them have Chinese faces (Fig. 659). The tile of 1262, found in Varamin, near Tehran, is, on the contrary, decorated with Persian arabesques alone. Two such tiles are located in the Berlin Art and Industry Museum. The aforementioned buildings in Solaniye and Tavriz (see fig. 657) serve as proof that in the 14th and 15th centuries. preferably used mosaic tiles with a blue pattern on the blue background. Nevertheless, in parallel with the mosaic technique, the production of tiles with a golden sheen was developed, on which animal figures and floral ornaments sometimes appeared, molded in relief and surrounded by blue frames. But the real faience with a light background, painted in several colors, was made mainly in the XVI century under Abbas the Great. At that time, whole wall paintings were executed from tile in non-religious buildings. Scenes of battles and hunting were borrowed from poets, genre scenes played out in the luxurious groves of cypress trees and Chinar - from real life. Similar tiled paintings were located in Isfahan in the 40-column pavilion; one of them, stored in the South Kensington Museum, depicts noble women spending time in the garden. Similar pictures are in the Berlin and Nuremberg art-industrial museums. In some types of people, Chinese influence is reflected in some places, but the general character of the composition and accessories is quite Persian. In a later time, the Safavids for decorating Persian buildings began to be used more often in semi-faience painted with glaze depicting figures. In 1900, Dr. Fr. Sarah was exhibited in Dresden Persian tile of all varieties from his own collection, made in Persia.

Persian manufacture of pottery developed in parallel with the production of construction tiles. The fragments of faience with figures of women painted in golden glaze glaze, located in the South Kensington Museum, originate from the ruins of Ray, destroyed in 1221. In London collections there are whole vases of this kind. Wales published images of vases with a golden sheen and multicolored additives dating back to the 12th century. The decoration of the later Persian vessels with metallic luster served as images of mainly bouquets of natural flowers. But the most common genus of Persian pottery is semi-faience, painted under the glaze. As the oldest of his surviving samples can be pointed to five plates of the XIII and XIV centuries, belonging to Mr. Wales in London. Drawings on them, filled with few colors (blue, green), surrounded by wide black outlines. They also have Chinese influence. In fact, we know that even the grandson of Genghis Khan settled Chinese artisans in Persia, and Abbas the Great called Chinese artists to Isfahan; In addition, in the 17th century, when Chinese porcelain, painted with blue patterns on a white background, flooded Europe and Persia, China’s influence on the ornamentation of Persian semi-earthenware ceramics increased. At this time, even its own factory of hard porcelain originated in Persia. Only vessels made, probably in the Kiempani province, with an original, harmonious chord of three colors, blue, red and green, retained a purely Persian character.

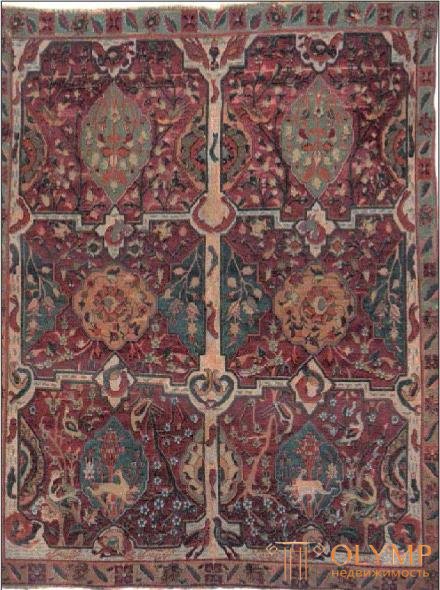

The walls of the Persian mosques and palaces are covered with colorful tiles, and the floors are covered with soft multi-colored carpets. In general, carpets play an important role in the Persian home environment. We have already talked about the technology of their production. Apparently, for the first time, the Persians of the Sassanid times borrowed it from peoples more cultural than they, and artistically developed it in their homeland. It is known that not all that is brought to Europe under the name of "Persian carpets" really comes from Persia; many products of this kind are products of the entire vast region of Western Asia. We would go too far if we began to list all that Yul wrote. Lessing, V. Bode, A. Rigl, I. Karabasek and the publishers of a large work on the carpets of the Vienna Trade Museum regarding ancient oriental carpets, which now play such a prominent role, if not in art, then in the life of artists. Lessing and Bode, based on the images of carpets in Italian, German, Dutch and Spanish Renaissance paintings, produced particularly important chronological definitions; but the Persian origin of the most ancient carpets found in the paintings is not only not proven, but also unlikely.

The ancient description of the Sassanid era carpet, representing "a garden cut by paths and streams with lovely spring flowers", most of all resembles the luxurious carpets that are the property of Dr. Alb. Fidgore, in Vienna (Fig. 660) and Professor Sydney Colvin in London. Both are depicted in the form of landscapes, similar to the ancient Egyptian landscapes, like gardens, with fishes in streams and birds in the bushes. On the Viennese carpet, moreover, are depicted under the trees antelope. Chinese influence is not noticeable here, at least in the London Carpet, which is considered more ancient than the Viennese. Some of the correctness of the location of the image indicates that these carpets or their patterns, the time of manufacture of which until now could not be determined precisely, at least, are older than the carpets of the XVI and XVII centuries. with animal figures.

The magnificent carpet brought by T. Graf to Vienna with a gold and silver background, decorated in the direction of its width with the image of six niches next to each other with gables and bouquets of stylized flowers in them, according to I. Karabasek, who dedicated a whole book to this carpet sample Susandzhirdskogo "needle painting", which is mentioned by writers. The scientist refers this carpet to the XIV century. However, in this area of research is not yet completed.

Magnificent carpets with animal figures made under Abbas the Great are perfectly accurate. In the Berlin Old Museum is the best example of such products. The blue border of this carpet and also the blue shields on the sides of its middle field are filled with a Persian pattern of tendrils and flowers; in a large central shield on a pink background are depicted cranes flying between the stripes of clouds. In the corner fields with a pink background, human figures are placed, the main area of the carpet is creamy-yellow, and there is a thick group of trees, shrubs and flowers, with four-footed and feathered animals moving among them. The figures of people and many animal figures in which we recognize the mythical animals of the "Middle Empire" have a completely Chinese character; nevertheless, all this, taken together, all woven patterns and their dyes, is Persian.

On other carpets with animal figures, the background is no longer occupied by a forest thicket with trees and shrubs on the vine, but by a wreath of flowers and leaves. As the best example of such carpets, you can point to the hunting carpet of the Austrian emperor. On its middle shield, the coat of arms of the Ming dynasty of China, the struggle of the phoenix against the dragon, are repeated several times.

Fig. 660. Oriental carpet of the XIII century. According to wrigle

If you do not take into account the painting of the tile, the main branch of Islamic painting must be recognized Persian miniature. Persian miniatures are rarely found in public museums of major European cities. A. Gaye, who wrote the first essay on their history, based on its compilation exclusively on the samples he found in the Khedi Library in Cairo. But in 1893, so many Persian and Indian miniatures were collected from private individuals at an exhibition of Muslim art in Paris that Georges Marie found it possible, based only on them, to compose an "approximately" complete history of Persian-Indian miniature painting; then Ed.Blosch published a general review of her works.

Миниатюры домонгольского времени Персии, по-видимому, не сохранились. Даже от XV столетия едва ли дошла до нас хотя бы одна персидская картинка. Чаще встречаются миниатюры XVI в., всего же больше осталось их от XVII и XVIII столетий. В миниатюрах цветущей поры персидского искусства XVI в. ясно отражается влияние китайского искусства, и если, кроме него, указывают также на индийское влияние, то надо заметить, что индийская миниатюра этого времени была в существенных своих чертах персидской. Во всяком случае, живопись персиян, китайцев и индийцев была в этом веке во многих отношениях одинакова. Дальше контурного рисунка без теней, заполненного гуашью, не шла и персидская миниатюрная живопись. Лучшее из того, что производила она с самого начала, – это портреты; в них являются перед нами фигуры в персидских костюмах с персидскими чертами лица. Аксессуарам придается большое значение: одежда, домашняя утварь, седла и сбруя на лошадях часто выписаны гораздо тщательнее, чем фигуры и безжизненные, невыразительные лица; в пейзажах эта тщательность нередко создает настоящее настроение, отражающееся во всей картинке. Кроме портретов, которые были очень любимы, в миниатюрах воспроизводились бытовые сцены, и в особенности эпизоды из рассказов поэтов. Многие из сохранившихся персидских миниатюр помечены именами их мастеров, хотя до сей поры ни один из них не представляется нам определенной исторической личностью. "Молодая персидская принцесса" Магомета Юсуфа в коллекции Гонзе в Париже смахивает довольно сильно на китаянку. В этой же коллекции достоин внимания профильный портрет молодого персидского принца верхом на коне (рис. 661), отличающийся твердостью и строгостью рисунка и характерно персидской посадкой фигуры; напротив того, находящийся также у Гонзе портрет арабского ученого Мохиэддина, лениво сидящего на ковре, принадлежит к числу позднейших миниатюр, в которых видно уже индийское влияние.

Fig. 661. Prince on horseback. Persian miniature. By "Gazette des beaux-arts", 1893, II

According to Gayeh’s research in the Khediwa library, in the first half of the 16th century, Ahmed Tabrizi’s school was prominent . Its main representative was Kemameddin Behzad (c. 1455-1535 / 36), in his six large drawings for Bustan Saadi, who showed himself to be a gifted composer, a master to report on the animation of finely drawn scenes, and in his portrayal of the festival on the garden terrace very sensitive to nature painter of luxurious landscape and architectural backgrounds. The last of these miniatures is remarkable pictorial charm of the essay. The Legend of Yusuf and Lulikage (about Joseph and his wife Pentefrija) is notable for the expressive mobility of figures. The same illustrator as Behzad was enjoyed by another illustrator of Saadi, Jangir. One of his main paintings depicts the Persian tournament. The third artist of this group is Bohari; in his Ascension of the Prophet to Heaven, we see in the cloudy sky a host of winged angels, generally not much different from the angels of Christian paintings of the 15th century. Jami, in her two drawings for Divan Sheikh Ibrahim ibn-Muhammad el-Gulshani, is a landscape painter in more or less Chinese style, full, however, of Persian feeling. All these artists worked until the middle of the XVI century. When Shah Abbas the Great Indian Mani introduced an update to Persian painting. As they say, he painted delicate, imbued with a sense of painting with yellowed autumn trees, with the light effects of sunsets, fogs, promising effects. His miniature "Adam and Eve under the tree of the knowledge of good and evil" makes a strange impression, because in it the forefathers of humanity are depicted in luxurious Persian costumes. School Mani existed until the XVII century. Timur wrote small pictures with many figures. Shuja-ed-Daula introduced in 1640 a freer, and at the same time softer and stronger, method of writing. Kapoor was an experienced portrait painter of his time. Landscape painter Shabur achieved success in terms of knowledge of perspective. Reza Fariabih introduced the mystical element into Persian art. In the later painters, European features were more and more mixed with the Mongolian features of Persian art. In general, all Persian painting, as far as we can trace its past, has very little in common with the spirit of Islam.

In the historical review of the Mohammedan art, it is most convenient to go from Persia to India in a detour way, through Central Asia and its main city Samarkand, to whose architectural monuments Zdenko Schubert von Soldern dedicated a special work. Samarkand, who was dominated by the Arabs first, and then the Seljuks, in 1221 fell into the hands of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan. But the capital and residence of the Mongolian state of the Tatar-Mongols, this city became only in 1369, with Timur (Tamerlane), a descendant of Genghis Khan, who planned to conquer all of Asia from here and command it. Like most conquerors, Timur tried to make his capital the focus of the arts and sciences. It is known that there were architects, mosaics and plasterers, called them from Isfahan and Shiraz, and sculptors drawn from India. Indeed, the magnificent Samarkand buildings of Timur and his successors, partly preserved, partly lying in ruins, testify to their belonging to Persian art: high portals such as niches, domes on vestibules, almost exclusively keeled arches, luxurious tiled and mosaic ornaments of blue, blue, green and white colors they have a completely Persian character. Local features include pumpkin-shaped domes, low round corner towers, quadrangular fences and hexagons, which make up the transition from the square shape of the dome part to the round platform of the dome.

From the old palace of Timur, later transformed into a Russian fortress, apparently, only a few things survived. In Samarkand, mainly tombs and high schools (madrasas) survived. Mosques, usually connected to burials, and madrasas, for the most part, have the form of quadrangular halls with quadrangular niches and a large central dome. The tomb of Timur is one of the most magnificent ruins in Samarkand. It is a quadrilateral, the transition from which to the dome of the dome are octagons. Niches are decorated with luxurious stalactite vaults. The walls are lined with alabaster and jasper plates. A mosaic strip of a meander is wrapped around the only surviving minaret. From among the Bibi-Khanym-Madrassa madrasah, founded by Timur in 1399, it is distinguished by its rare octagonal minarets, smooth, not ribbed, resembling a melon with the main dome and stalactite cornice under it.

Then, among the other most beautiful mausoleums of the time of Timur, belongs the tomb of one of his sisters on the burial mound of Shakhi Zinda. The magnificently framed portal and the melon dome of this building are remarkable, and inside there are tiled decorations with magnificent plant arabesques and weaving of ribbons. The finest madrasah of a later time is located on Registan Square. The huge entrance niche is magnificent here, four high middle niches on each of the four sides of the courtyard, on the sides of which there are two smaller niches, with keel-shaped top, one above the other. Among the ornaments here are striking with their rarity two figures of animals (foxes). However, this building was erected only in 1610, that is, when the former brilliance of Samarkand began to fade.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)