Fig. 71. Savior on the throne. Fresco in the church of S. Maria delle Grazie near Carpagnano. By Dil

While in the artistic and cultural areas of the Christian East, whose limits narrowed the spread of Islam, ancient Hellenism with an admixture of ancient Asian elements continued to underlie the new Greek art in the West, under the direct, as one might think, although not exclusively influenced by the Syrian, Egyptian and Asia Minor monastic art (see I, 1), formed the Latin-German mixture, which should belong to the future. In Upper and Middle Italy, the Lombards followed the Goths, the Lombards followed the Franks. On the contrary, a significant part of Lower Italy, Ancient Greece, which had never ceased to speak Greek, was in fact still under the authority of the Greek emperors in the 9th and 10th centuries. Byzantine art and Byzantine civilization, to which Ravenna and Venice were in the North, used in this era in Lower Italy, in Calabria, Basilicata and Terra d'Otranto, still had full citizenship. Following Dilya, we will focus primarily on this Byzantine art of Lower Italy. In the field of architecture for the art direction under consideration, a small chapel of St. Mark in Rossano IX or X century; its five domes, as in more ancient churches, do not yet have cylindrical drums. The square plan is divided into nine smaller squares by four middle pillars; the three eastern squares end in semicircular absides of the same size. The interior of the chapel forms an elegant, strictly closed whole. In the area of painting by the X century and the beginning of XI, first of all some Byzantine frescoes belong in the crypt of the church of Santa Maria della Grazie near Carpagnano (in Terra d'Otranto). The image of the Savior sitting on the throne, with long hair, a small beard, a long straight nose, plump lips, well-modeled cheeks and hands (Fig. 71), is attributed to 959 g .; The other Christ Pantocrator, of a more ascetic and sullen appearance, was painted in 1020. But the most remarkable fresco painting of this time in Lower Italy is preserved on the walls of one cruciform chapel of the Benedictine monastery in San Vincenzo, on r. Volturno. It is performed between 826 and 843. commissioned by Abbot Epifanio, who himself is represented here at the feet of the crucified Savior. In these frescoes, which are Byzantine in their basic character, modeled by green shadows, some Western European features are visible. Finally, you should take a look at the North and mention the purely Byzantine frescoes painted by the Greek monks of the Macedonian period in the church of Sts. Marie the Ancients in Rome (see above), whose scanty remnants are a sumptuous female figure like Juno beside Madonna and an unknown saint, discovered under layers of later painting, Venturi considered to be among the best works of Byzantine art.

Even more curious for the history of the development of artistic forms are the art monuments of those localities of Upper and Middle Italy, which for centuries had actually been under the rule of the Germans. The semi-cultural peoples of the North, of course, could not give much to the Italians. Roman-Hellenistic antiquity, no matter how far its decomposition proceeded and no matter how saturated it was with Byzantine, it continued to dominate in the field of intellectual and spiritual culture, language and art in the epoch of its decline. Nevertheless, the blond conquerors left in Italy some traces of their native art they brought from the North.

In Italian church architecture and in this period, Germanic influences are almost imperceptible; they could be found only in the deterioration and coarsening of all the individual forms. Cattaneo, in its history of Italian architecture, did not quite successfully designate the architecture of the sixth and seventh centuries as Latin-barbaric, of the eighth century — as Byzantine-barbaric, and, hardly more successful — of two centuries, from 800 to 1000, as Italian Byzantine. After Cattaneo, the Italian architecture of these centuries by Rivoira, especially the architecture of those churches that should be viewed as components of the transition to the developed Lombard style of the second half of the 11th and 12th centuries, was studied very thoroughly, although somewhat one-sidedly. The Dolombard, in the terms of Rivoira, especially the Lombard buildings of this kind (the Lombards, whose rule in Italy lasted from 568 to 774, actually did not have any effect on them), are dissected by lysens (flat protrusions) and decorated with deaf arches and a cornice consisting from a series of small, often braced, hanging arches. The ornamental motifs of this genus, which we have already met in Christian architecture, are borrowed here, undoubtedly, from the more ancient parish churches. Of the three naves, the middle one also has a wooden covering, while the side ones are sometimes covered with cross vaults. As a transitional stage to the later outer colonnades, at the top, between the hollow arches, a row of simple, semicircular niches often appears on the wall of the apse.

In the Carolingian and Ottoman times, the parish church in Arliano near Lucca and the ancient part of the church of Sts. Petra in Tuscanella, VIII or IX century, show how this style was formed in Central Italy. In the North, the first place is occupied by the Church of San Salvatore in Bresch and the ancient parts of the Church of Sts. Ambrose in Milan. The earliest examples of the bell towers, which in this epoch, as in the East, are still associated with the church body, are the belltowers of the cathedral in Ivrea (972–1010) and the church in the name of Our Lady of Susa (1021). In the Hebrew cathedral, moreover, there is already a low roundabout around the choir, covered with a boxed vault; in the church of sv. Abbondia, near Como (1013) are the oldest, according to the testimony of Rivoira, real impost capitals with rounded corners at the bottom, and in the side aisles of the church of Sts. Flaviana in Montefiascone - the first cross vaults with convex ribs.

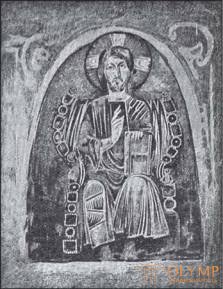

Fig. 72. The plan of the church of sv. Ambrose in Milan. Across cattaneo

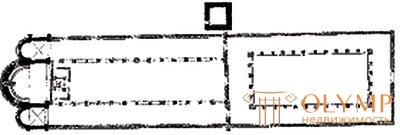

The churches of the central type in Italy, which belonged to this time, almost never occur. Church of sv. The Satire in Milan (879), which has a square plan with semicircular niches on each side, as in ancient Armenian churches, with boxed arches over the branches of the transept, with cross arches at the corners and a dome over the central space, is an exception. This can also be attributed to the amazing structure of the Baptistery of the Cathedral of the city of Biella (circa 975), with an apse in each of the four sides. However, the vast majority of Italian churches throughout this era belonged to the category of three-nave basil with a flat coating. Even in Venice, the church of sv. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the brand belonged to this category and only in the subsequent period received its current form of a Byzantine five-domed temple. It is characteristic of Italian basilicas of the time that the altar side, as in the Eastern churches, has three apses, according to the number of naves: it appears for the first time in the church of Santa Maria in Kozmedin (772-795), then in the church of Santa Maria in Dominica (817 –824) in Rome, in the basilic crypt belonging to the end of the VIII century under the Round Church (La Rotonda) of the city of Brescia, which Cattaneo rightly referred only to the XI century, and finally in the part of the Church of Sts. Ambrose in Milan (Fig. 72). Equally, the Italian capitals of the columns of this time, which only rarely were taken from ancient Roman buildings, are impurities and distortions, transformations and neoplasms based on traditional Greco-Roman and Byzantine forms; hints of Germanic ornamentation are rarely seen. Capitals of columns - spoiled versions of the Corinthian order and the Roman composite. It is interesting to compare the capital of the eighth century. Church of Santa Maria in Kozmedin in Rome (Fig. 73) with a capital of the 9th century. church of sv. Satire in Milan (fig. 74) or a capital of the beginning of the 8th century. church of sv. George (S. Giorgio di Valpolicella) near Verona (Fig. 75) with a later, although also VIII century, capital, stored in the Museum of Perugia (Fig. 76). The barbaric style of the last two capitals undoubtedly has a German-Lombard shade.

Fig. 73. The capital in the church of Sts. Maria in Kozmedin in Rome. Across cattaneo

Fig. 74. The capital in the church of Sts. Satire in Milan. Across cattaneo

Fig. 75. The arch of the civoria in the church of sv. George near Verona. Across cattaneo

Fig. 76. The capital that is stored in the museum of Perugia. Across cattaneo

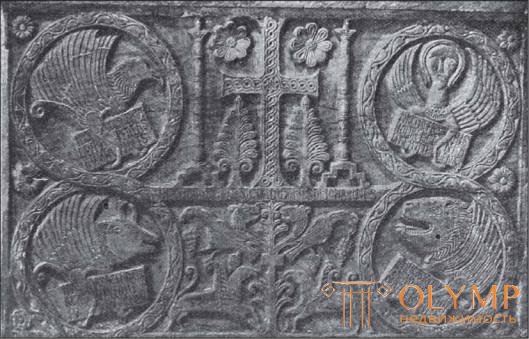

In the ornamental art of Upper and Middle Italy, especially in the ornamental sculpture of this epoch, the first place is occupied by Lombard products, a peculiar style of which is produced only by the end of the 5th century. The Lombards, as shown by the finds collected in the museums of Brescia, Cividale and Perugia, from their northern homeland brought to Italy that animal and ribbon ornament, which we had already learned, speaking of pagan Merovingian art (see t. 1, fig. 546) . Only at the end of their rule in Italy did they begin to incorporate elements of this northern style in a mixture of Roman and Byzantine motifs and Christian symbols in stone ornaments. The question of the “Langobard tracks in the Italian plastics of the first millennium” was investigated by Zimmermann and Stückelberg, whose conclusions, however, were met in Italy, where they were opposed by Fontana and others, less success than in Germany. That this stone ornamentation was not Byzantine, but Lombard, was recognized by Rivoyra, at the same time denying in it - not quite consistently - any northern, German layer. So, speaking of the distributors of this ornamentation, the partnership of architects and sculptors of the city of Como, maestranze comacine, he names among the masters, however, the names and meaning of which are still being debated, such purely German names, such as Rouodpert, for example. Two-, three-and multi-row ribbon braids that form the main part of this ornamental style, of course, were at that time common in the art of all nations, as a legacy of gray eastern antiquity; as for the special (irregular) type of ribbon weaving connected with animal motifs, typical of the Germanic Merovingian style, its traces are not always found in the Lombardo-Italian ornamental plastics with full clarity, but sometimes they can still be ascertained; On the other hand, some variants of ribbon and belt patterns are so different from Byzantine and Roman braids that they are forced to recognize them as Lombards. Such are the splitting of each individual tape into three deep cuts, a round weave with a quadrangular frame inserted in it, which Stückelberg compared to the “bottom of the basket”, as well as ribbons precipitated by spiral hooks resembling gothic crabs. Along with them are found, especially at a later time, astragalus (pearl cords), rows and vegetative curls of Hellenistic-Byzantine ornamentation; spiral curls often get inorganic appendages in the form of spokes and thus turn into "wheel-like curls" (Fig. 77). To fill free space, leaves, bunches of grapes, crosses are used, less often - animals of Christian symbolism. Sometimes there are also human figures, but depicted to the extreme ineptly. From its homeland, Upper Italy, the Lombard ornamental art penetrated into Central Italy and southern France. Among the main monuments of the Lombard ornamentation belong (partly added later) the relief slabs of the fence around the baptismal reservoir in Cividale, in Friul, built in 737. On these plates there is no shortage of antique elements, there are even vultures; but the manner in which one of them, commissioned by Patriarch Siegwald (762-776), stylized animal heads and palmettes, turned into Christmas trees, especially the very schematically interpreted symbols of evangelicals, expose not late Roman and not Byzantine style, but North German . The pear-shaped head of an angel, symbolizing St. Matthew (Fig. 78); The head of the Savior is similar to it on the front of the altar in the church of San Martino in Cividale. In later works, such as, for example, in the ciborium above the altar of St.. Elevkadiya in the church of sv. Apollinaria in Classe near Ravenna, the Byzantine elements are becoming more and more in the Lombard style.

While the Italian stone plastic remains barbaric, the Italian ivory carving continues to preserve antique elements, with a certain commonality of style connecting it with simultaneous northern, Carolingian bone reliefs. By 752 there is an ivory disc stored in the Cividale Museum, “Pax” [1] of the Duke of Urs - worked out, as can be seen from the inscription on it, for Urs, Duke of Cheneda. Framed in acanthus leaves is a Crucifix; there is no clothing on the Savior except a wide apron; both legs of the Crucified One, as always at this time, are depicted nailed to the cross each separately. Above, near the cross, the sun and the moon are represented in the form of half-figures in narrow robes with sleeves, forming small folds; the figures standing under the cross are clumsy and short. However, the figure of the Savior is of the correct proportions, and in the technique of the naked body a good school is still felt. Other Carolingian plates and ivory boxes are matched by Clemen, who attributed to them Italian origin; others are published by Greven.

Fig. 77. Langobard wheel-shaped ornament. According to Stückelberg

No signs of German influence can be found in Upper Italian and Middle Italian painting of the time under consideration, sometimes imbued with Byzantine currents, but generally distinctively barbaric. Painting miniatures at this time in Italy almost did not exist. Near the abundance of Byzantine and Frankish facial manuscripts Italy X century. it can only boast of the meager and crudely illustrated Exultet scrolls [2]. But mosaic painting, which, for the sake of greater consistency of exposition, we already traced back to Rome in the ninth century (see fig. 39), in the second half came to a complete decline there. Between the mosaic in the apse of the church of sv. Mark (827–844) and mosaic in the form of the upper church of St.. Clement (about 1112), therefore for two and a half centuries, we do not have monuments of Roman mosaic painting at all. The absede mosaic of the church of st. Ambrose in Milan belongs - in which we agree with Cattaneo - not the ninth century, but, at the earliest, the end of the eleventh century. However, the need to decorate the walls of the temples with sacred images did not disappear along with solid, but too expensive mosaic work: cheaper fresco painting took its place. The remains of the frescoes of 996 (Christ, Our Lady, Michael the Archangel, etc.) in a small chapel of St. Nazaria in Verona. Venturi drew attention to their kinship with German frescoes and miniatures of the Ottonian century. The full development of Western features of fresco painting we meet in this era in wall paintings of Rome and its environs. VIII century belong to numerous frescoes in the church of St.. Mary of the Ancient, depicting scenes from the lives of the saints. The 9th and 10th centuries and the beginning of the 11th century include: “Christ in glory” on the abscess arch of the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome and in the mosaic style of the frescoes of the church of St. Elijah, between Nepi and Civita Castellana, as well as those between the ancient pilasters, unfortunately rewritten, scenes of the Passion of the Lord and the figures of the saints in the church of Sts. Urbana on Via Appia near Rome. In churches of sv. Elijah and Urbana again we meet the signatures of artists; but their names, completely unknown, do not tell us anything. The best concept about the art of this time is given by the frescoes of the crypt in the Lower Church of St.. Clement in Rome, written before 1084 - the time of the destruction of the Upper Church. The ninth century includes images of Christ sitting on the throne between the archangels Michael and Gabriel, in the partyx, as well as the Crucifixion, the Descent of the Savior into Hell, the Resurrection of Christ and the Ascension of the Virgin to heaven, in the middle nave on the left, closer to the entrance. The contours are black, the tones of the body are yellowish, but in the drawing it is possible, although with difficulty, to notice the ancient traditions. By the 10th century, which marks the deepest decline of art in Italy, it refers, among other things, to the Savior on the threshold of hell, at the end of the right side nave of the same church. Here, for the first time, the real devil is depicted holding Adam by the leg.In the frescoes of the partyx and the middle nave, belonging to the XI century and depicting scenes from the lives of St.. Clement and Alexia are already visible features of the new style, consideration of which goes beyond the period occupying us. Heads with rosy cheeks become smaller, but more expressive; body members get bold movements; what else can not convey facial features, then tries to express gestures.

Fig. 78. Sigwald stove decorated with relief. Part of the baptismal font in Cividale. With photos of Vla

Quite different than in Italy, was the position of early medieval art in Spain. The green banner of the prophet flew over Sierra Nevada and over the whole south of Spain. In the first volume of this essay, we became acquainted with the lush flowering that Moorish art reached in these centuries on the soil of southern Spain. Christian art was pushed to the extreme north of the peninsula, mainly in the kingdom of Leon. In Oviedo, Villaviciosa and some neighboring places, church buildings of the 8th and 10th centuries have been preserved; not revealing a big flight of artistic fantasy, they testify, however, to an independent, although in connection with the simultaneous development of southern French art, the reworking of the ancient Christian tradition.

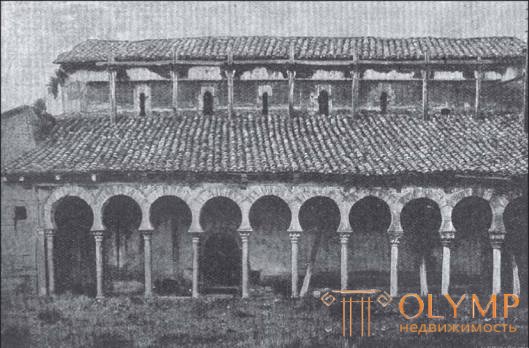

At the beginning of the era we are considering is the so-called Camera-Santa of the 9th century at the Gothic cathedral in Oviedo: this is a kind of crypt, covered with a box-shaped vault, with six pilasters, each of which is decorated with two figures of apostles; the latter are strongly elongated, but not completely devoid of artistry. The church of Santa Maria de Naranco in Oviedo has the same appearance, along the longitudinal sides of which the outer colonnades first appear as a Spanish feature, constituting in some way an intermediate step between the early Christian narthex and medieval cloister galleries. The three-nave basilica with a flat covering in the period under consideration belongs to the Benedictine church of San Salvador de Valdédios consecrated in 893 near Villaviciosa, San Salvador. There is no transept in it, the choir is separated by columns and arches from the longitudinal body, along the outer walls of which there is also a beautiful colonnade. X century belongs to the three-nave, rectangular in plan, but already equipped with a transept church of San Miguel de Escalade near Leon. It is characteristic that its outer gallery is supported by Moorish horseshoe-shaped arches (Fig. 79), in which the Arab influence clearly manifested from the south of the peninsula. Capitals of the columns resemble a Corinthian order. The interior of this church is dominated by a primitively simple, jagged ornament. The true flowering of Spanish art begins, however, only from the second half of the eleventh century.

Fig. 79. Arcade gallery outside the longitudinal building of the church of San Miguel de Escalade near Leon. According to Junggendel and Gurlitt

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)