On the happy islands washed by the North Sea, Christianity had already taken deep roots at a very early time; when the Anglo-Saxon conquest put an end to the spread of Christianity in the south of England, the latter found fruitful soil on the other side of the Irish Sea, in green Irene, whose apostle, Patrician (St. Patrick), died in 492. Ancient Christian art, brought along with the new by faith, it took here, on the Celtic shores, where the Romans did not go, a peculiar direction in many respects, a mixture of child incompetence with a conscious desire for a specific goal. This direction is observed primarily in the ornamental art. There is no doubt that the Irish ornamentation, in addition to Christian-antique (precisely Alexandrian) and Franco-Merowing elements, also contains local, Celto-Irish. The teaching, which denies the existence of any kind of independent ornamental art in Central and Northern Europe, seems to us, already looking at the art of primitive peoples, not to withstand criticism. Even with the lowest appreciation of borrowed motifs of Irish ornamentation, the way the Irish managed to translate alien elements into a new, vividly national art, one cannot but see independent artistic creativity. From Ireland, this new art, together with Christianity, was transferred by the Irish clergy to Anglo-Saxon England and to the remaining Celtic Scotland in large parts, and then to the continent. Already at the beginning of the 7th century, the Irishman Kolumban was preaching on Lake Constance; his compatriot Gall founded the St. Gallen Abbey in 614; the great Anglo-Saxon Winfried (St. Boniface), from 747, the Archbishop of Mainz, was killed when the Frisians converted to Christianity (in 755). The famous scientist Alcuin, friend and adviser to Charlemagne, born in 735 in York, was Anglo-Saxon, like Winfried.

Both in Ireland and in England and Scotland, many monuments of pre-Romanesque Christian architecture have been preserved, but the time of their appearance is unreliable, and artistic forms are poor. We draw our knowledge of this architecture for England and Ireland from the old works of Britton and Petrie, and for Scotland from the works of Allen and Anderson. In the centuries in question, wooden architecture dominated the British Isles. However, alongside it, it develops quite early, adjoining to the megalithic structures of these countries (see t. 1, fig. 10), stone church architecture. It is interesting that in the oldest stone churches of Ireland and Scotland, mostly consisting of one undifferentiated room, there are still prehistoric forms; so, for example, the windows of the church of sv. Kemina (fig. 80) is topped with two stone slabs set at an angle; likewise, the door arches are sometimes simply hollowed out or formed by the release of plates overlapping one another. The transition to this arch can be seen in such buildings, such as, for example, the church of the Monastic Island near Killelo and the church of Sts. Columbus in Kels, attributable to the beginning of the X century. Particularly characteristic of Irish and Scottish church architecture of the 10th and 11th centuries are slender, pointed circular towers at the top, usually standing at some distance from the churches themselves. We have met similar towers before in Ravenna. The oldest architectural style belonged to the tower in Lösk in Kondalkin; the arches at the gates of the towers in Milik and Monesterbois are cut from three to five stones; the slightly more developed forms represent the towers in Devenish and Killel. In the church of sv. The Kevin in Glendaló tower rises above the roof, and at the ancient church in Dirnes two round towers are already on the edges of the western facade. In England, where the Roman basilic pattern, rooted in ancient Christian time, was also maintained in the period under consideration, the architecture of the Anglo-Saxon churches presents other features. For example, the walls of the quadrangular tower of the ancient church of Count Barton near Northampton vividly resemble a wooden checkered structure (half-timbered house), and the columns of complex windows (Fig. 81), especially the upper tier, along the edge, imitate their roundness, banners and protuberances turned from wood .

Fig. 80. Window in the church of sv. Kemina in Ireland. By stokes

Fig. 81. Columns of complex windows on the tower of the Church of Count Barton near Northampton. By von Reber

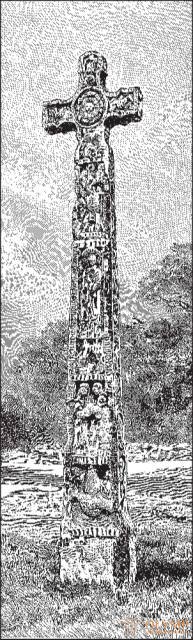

The transition from stone architecture to plastic stone is made up by roadside crosses, which are among the most distinctive monuments of early medieval Christian art in Ireland, Scotland and England. At the most characteristic of these Celtic monuments, the corners between the branches of the cross are rounded; the middle circle, which serves as a connection between the branches, is smooth; with the further development of the forms of these crosses, “windows” appear in them, that is, the openings between the middle circle and the corners, the circle itself becomes smaller, and the whole shape of the cross becomes slimmer.

Ornaments covering the surfaces and edges of Irish and Anglo-Saxon crosses and gravestones differ in extraordinary wealth. Here we meet all the Irish and all Anglo-Saxon ornamentation described by us, in their commonality and differences, in the first volume (see t. 1, fig. 546): geometric elements, ornaments in the form of the letters T and Z, diagonal decoration, triangular, cuboid and stepped forms, different versions of the spiral, especially an open spiral, or a tubular-spiral ornament (Fig. 82), and, finally, an unchanged braid with narrow loops. To these motifs, animal figures, which do not play in stone ornamentation of that role, as in metal products and miniatures, are gradually mixed in. But an important role is played by relief images of sacred persons and events. These reliefs, still insufficiently studied with respect to forms, reproduce, with some variations, the ancient Christian artistic cycles of the Roman sarcophagi with the addition of plots invented at a later time. Crucifixion is rarely absent, an image of Christ appears in glory. Then follow the figures of the saints and scenes from their lives. Separate forms are childishly primitive, but even in them the beginnings of artistic understanding are visible, and thanks to the strictly sequential filling of space, in most cases an excellent general effect is achieved.

Fig. 82. Pipe-helix Irish ornament. By stokes

The inscriptions on the Irish crosses of the genus in question indicate, at the earliest, the X century. But some Anglo-Saxon crosses are believed to be much older. The oldest of them, decorated with braids and coarse images of evangelists Collingham Cross (in Yorkshire), erected, as has been proved, in 651; A beautiful Rutuel cross in Scotland is usually ascribed more often to others to the 7th century (fig. 83); but, as Mary Stokes proved, he is hardly older than Irish crosses. In addition to the graceful arabesques, among which the motive of a winding stem with big birds and small leaves, scenes from the New Testament and the lives of the saints (hermits Anthony and Paul in the desert) with strongly elongated figures draws attention to themselves, the hymn of the First Cross is carved Anglo-Saxon Christian poet Kedmon (c. 680). By the eighth century, Clemen carried the Anglo-Saxon crosses at Olnmous, Gaknäs, and Thorngill, and to the ninth century. and the first half of the X century. - Awkward cross in an ancient chapel in Oldbar and a beautiful cross in Carew in Pembrokeshire. The highest development of this art reaches in the X century, and on Irish soil. In particular, the crosses in Clonmacnois, Mönsterbois and Durro are worth being mentioned. On all these crosses there is an image of the Crucifixion. At the foot of the cross, 904, in Klonmaknoys, King Flann is represented, with a long beard, and on the cross in Monesterbois, 924, Miridech, the abbot of a local monastery. The relief of these crosses is rather high, the figures are clumsy and angular, but they are executed carefully and not completely lifeless.

Fig. 83. Rutuel roadside cross in Scotland. From the photo

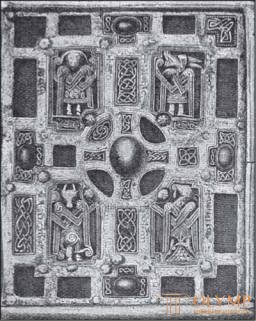

All the wealth of Irish ornamentation is displayed in metal art and craft products. Some development of luxurious forms of tape and linear twists will not escape the attentive observer. The “pipe” motif, with its double helix lines, which, diverging to form a kind of socket, disappears shortly after 1000. Plant motifs and after this time are not found on Irish metal products. Animal ornament becomes more varied only after 1000. The Irish iron bells, preserved in significant numbers, actually are not included in the circle of art history, but we are interested in the luxuriously ornamented cases that served as repositories of these bells from the XI century, in which they already acquired meaning. relics. Case bells of st. Patrick, in the collection of the Irish Academy in Dublin, despite its ancient ornamentation, was made only around 1091. Similarly, expensive old books, instead of receiving luxurious binders, were stored in luxurious caskets. On the cover manufactured between 1001 and 1025. the caskets of the Devenish Gospel, in the same collection, depicted (Fig. 84) evangelists: three of them were given the heads of symbolic animals; their legs only vaguely resemble human, and their hands are replaced with ribbons. The eighth century belonged to the famous, glittering gold, silver, copper, bronze and brass bowl from Arde and a magnificent round buckle of light bronze from Tera-Bruch, both in the Museum of the Irish Academy. In the mass of ornamental motifs covering these works, the main theme is also played by the trumpet motif. The luxury of Late Irish ornamentation is most pronounced on certain episcopal staffs. The most magnificent of them is the staff of Bishop Clonmacnois, in the museum of the Irish Academy. Made hardly earlier than the 11th century, this staff is decorated with a very complex ribbon ornament with human and animal heads, and its curved handle is seated with animal figures biting each other at the back of the body; a fragment of the Greek meander is mixed with these motifs; among animals appears winged dragon.

Fig. 84. Irish metal casket cover. By stokes

The ornamentation of Irish miniatures is especially intricate and varied, with which the capital works of Westwood and Count de Bastard and the studies of Gilbert, Middleton, Mary Stokes and Sophus Muller present us. It is possible, as Middleton pointed out, that Irish ornamentation was invented for metal products proper and only later was transferred from them to the calligraphic works of monastic cells; in any case, the ornamentation of miniatures favorably differs from the ornamentation of metal products with greater freedom of technology and richness of colors, finally reaching the full spectrum.

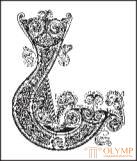

The initial letters in Irish manuscripts are very developed and decorated with ornaments. Animal motifs are connected in them with the motifs of ribbon weaving. Four-legged stretched into the tape; bird heads are impaled on their long, ribbon-like necks. Human figures are completely distorted. Sacred persons, even where they are the main images and occupy the central place, are treated flatly and schematically. Their beards and hair are turned into ribbons with twisted ends, the members often disappear altogether. As in primitive art, the figure is placed either completely en face, or completely in profile. Facial features are indicated by geometric lines, clothing - again, ribbons. But the endless patience and love with which these miniatures are written, and the remarkable purity and thoroughness of their work testify to the real artistic inspiration of their performers.

Fig. 85. Ornamented page from Book of Durrow. By stokes

From VII to X century, there is a transition of ornamental motifs from great simplicity to more and more entangled plexuses and at the same time an increase in the number of colors used for them: blue, purple and violet colors join the former yellow, red, green and black. Gold in the ancient Irish painting of miniatures is completely absent. Over time, simple stylized leaves begin to approach the forms of the Romanesque character, imitating the acantha; snakes and winged dragons join the four-footed and birds. The graceful motif of a spiral in the form of a pipe and in miniature does not survive the beginning of the XI century. From the middle of this century begins a noticeable decline.

At the head of the development of the Irish ornamentation of manuscripts should, in our opinion, be placed stored in the College of St. Trinity in Dublin is a gospel originating from Durro (Book of Durrow). It refers to the time of St. Columbus (died in 598), but in its style it is hardly older than 650 g. Ornamented it is still relatively simple and clear (Fig. 85).

Before the Gospel of Matthew there is a rather fanciful image of an angel in the form of a bearded man. Symbolic animals of the other three evangelists are covered with geometric patterns.

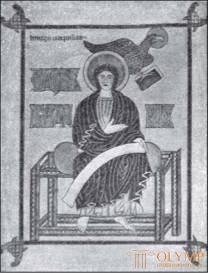

The most significant and luxurious of the Irish Gospels Book of Kells is also stored in the Dublin College of the Holy Trinity. The time of writing was defined differently: most researchers attributed this Gospel to the 7th century, and some even to the 6th century, and Gilbert admitted that it belongs to the 10th century; Sophus Muller, on the basis of the intricacies of the forms and the richness of the colors of his ornamentation, pushed this date back to 900 g. But it is hardly younger than the Gospel of Ketbert, which, as has been proved, was written at the beginning of the VIII century (see Fig. 88). Human heads and whole figures are interwoven here in different places in the tape twists of capital letters (Fig. 86). Images of the Evangelists are placed in the middle of the individual sheets, then the Mother of God with the Baby in the bosom (Fig. 87) and some Evangelical scenes, for example, the capture of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. As far as the ornamentation of this Gospel is full of peculiar charms, his figured compositions performed in a calligraphic style are just as repulsive, anti-artistic.

Fig . 86. Initial L of Book of Durrow. By stokes

Fig. 87. Madonna. One of the miniatures of Book of Kells. By springer

In addition to the College of the Holy Trinity in Dublin and the British Museum in London, Irish manuscripts of the same style as above and later are also found in many collections of Great Britain and the continent. The manuscripts of the St. Gallen monastery are, as it can be supposed, made in part by Irish monks, whom he brought with him. Gaul.

The passage to the Anglo-Saxon illustrated manuscripts is the often-quoted Gospel of Koetbert (aka the Dergøm Gospel), which is kept in the British Museum. Another St. Columbus founded a monastery on Ion, a Celtic island off the western coast of Scotland, which became one of the main centers of Irish miniature painting. Among the artistic colonies of Jonah was Lindisfarne, near Dergöm, in Northumberland. Here, on English soil, a school of miniaturists arose; here between 698 and 726 It was written by Anglo-Saxon Idfrith and illuminated by another Anglo-Saxon, theluwold, Gospel of St. Kobertta. The ornamentation of this manuscript is completely Irish, only the use of gold and silver scarring is new. But the sitting figures of the Evangelicals (Fig. 88) are very far from the calligraphic style of Irish images in their forms and manner of writing. They reflect the direct influence of Rome, the relationship with which the time of the Merovingian time is beyond doubt (see Fig. 38). The same style belongs to the magnificent Celto-Anglo-Saxon Gospel, the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg.

Fig. 88. The Evangelist John. One of the miniatures in the gospel of Koetbert. According to Property

Under King Alfred (871–901), Northumberland fell under Frankish influence. A pure Anglo-Saxon school of miniature painting arose.

By order of Bishop Ethelwold of Winchester, a magnificent “Collection of Church Blessings” (Benedictionale, 964) decorated with 30 miniatures the size of a sheet was written by the Duke of Devonshire. The fields of this manuscript are filled with Carolingian leaf ornament, and the miniatures, the plots of which are mostly taken from the earthly life of the Savior, are made in the German picturesque style of the Ottonian time.

Thus, in the XI and XII centuries and in England, the ground was prepared for the further success of art.How Irish-Anglo-Saxon art influenced the pagan Scandinavian North is indicated in the first volume, and we have already seen that Irish-Scandinavian art, immediately after the conversion of King Harald to Christianity, began to add some Christian motifs to ribbon and animal plexuses. On the rune stone from Jelling, set by Harald in memory of his parents, Christ is depicted in a crucified pose (vol. 1, fig. 541, c), supported by interlacing ribbons. Thus, one of the last works of pagan art of the Scandinavian North became one of the first works of its Christian art.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)