Italy, marching in the form of a long peninsula into the sea and connected with the whole world by trade and navigation, was not so generously endowed with the makings of artistry as its sister, Greece. However, it was still much earlier than in Greece, the unifying national self-consciousness awoke, and she began to sensibly perceive the art of the neighboring countries, to apply, process and partially develop. We already know that from the VII century. BC e. Sicily and southern Italy, thanks to the Hellenic colonization, became spiritually inseparable parts of Greece and from the very beginning they took an active part in the artistic aspirations of their metropolis. Even a few hundred years before Central Italy, the tribe of the Etruscans (tusks, tyrrhenes), which was strong and mysterious with respect to their origin, colonized. The Etruscans settled south and north of the Apennines; through the Tyrrhenian Sea, which received its name from them and near which their main cities were located, works of both Eastern and Greek art were imported to them and spread throughout Central Italy.

The self-consciousness of the Italian people was awakened first on the basis of citizenship. It awoke on the shores of the Tiber, in a small area of Latins, who, being crowded from the north by the state power of the Etruscans, and from the south by the spiritual strength of the Greeks, nevertheless conquered their neighbors first, then all of Italy, and finally the whole Western world. Rome - the focus of this territory, became the capital of the whole world, and Roman art took in all the rays of Hellenistic world art to give it a new shine before it slowly extinguished.

In pre- Etruscan and pre-Greek times we meet in Italy with traces of art from the Paleolithic, Neolithic and Bronze periods. But with the Mycenaean art of Greece it is impossible to compare absolutely nothing in Italy. Only in the early days of the Iron Age, which began in Italy from the 10th or 9th century. BC Oe., we find artistic creativity, any noteworthy. We owe it to the works of the Italian archaeologists, and the interpretation, besides them, is also to the northern scholars: Helbig, Undset, Belau and Montelius.

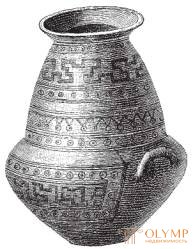

Fig. 460. A clay vessel of the most ancient villan period. By ranke

At the beginning of these prehistoric times of Italian art is the art of the most ancient stage of the Villanova, which received this name from the cemetery on the estate of Villanova, near Bologna. Local tombs belong to the category of so-called well, well- shaped (tombe a pozzo), that is, consisting of a pit dug vertically into the mine, ending at the bottom with a small chamber for an ash urn. The funeral urns were clay, molded by hand and ornamented with scratched, less often derived from paint patterns, which were usually placed in two strips on the throat and in the middle of the vase. These patterns are purely geometric in nature. Their main elements are triangles, quadrangles and circles, but the meander and the swastika also play an important role in them; By the meander joins, as in ancient American art, a stepped pattern, which is occasionally found on Greek soil. However, compared with the subtly felt correctness of the Greek Dipilonian style, the geometric ornamentation of Villanova seems ugly and self-willed. It is necessary to look at it as a product of barbaric art, which developed in parallel with the dipilonsky style. The considerations that Bölau in the treatise on the Villanova's ornamentation leads to as proof that her style originated from the Greek jewelry system, akin to the Dipilonian style, undoubtedly deserve attention, but are not quite convincing for us in our view that the main forms of geometric ornamentation are meander inclusive - the initial legacy of humanity. However, the earthen vessels of the Villan period, discovered in Central Italy, perhaps, should be considered even more ancient than those found in Northern Italy. It is most convenient to get acquainted with them by the samples that are in the Bologna Museum (Fig. 460).

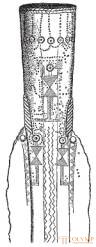

Fig. 461. Bronze spear tip of the most ancient villan period

Scratched ornaments of earthen vessels are repeated in ornaments engraved on cast bronze items originating from the tombs of the most ancient Villanian epoch, whereas larger forged items are usually decorated with convex ornaments. The figured motifs of engraving and knockout work are found in the form of roughly executed heads of birds and snakes, placed one against the other at the ends of the circles. As a completely authentic monument of figure-geometric Italian engraving, you can point to a bronze spearhead, Dresden Albertinum (Fig. 461). The bodies of the armless men depicted here, just as in the monkey image of the aueto tribe in Brazil (see Fig. 63), consist of two triangles facing each other, and the heads are made up of circles with a dot in the middle.

The somewhat later stage of the first iron age of Italy includes objects found in ordinary graves (tombe a fossa), which are beginning to be found from the time when, instead of burning, the bodies were buried. This change in the funeral ceremony can be attributed to the end of the 8th century. BC e. At this time, the movement was headed by Etruscan cities - Tarquinia (Cornetus), Vulci, Vetulonia, Faleria. The import of works of foreign, especially Greek, art is noticeably increasing. The other Greek cities of Southern Italy are already beginning to forge their products under purely Greek for their sales in Etruria, and this affects the products of the local middle Italian production. On knockout bronze vessels and shields from Cere (Cerveteri), Cornetto and Preneste, images of birds and horses appear more frequently. Fibulae in the form of still legless horsemen or birds with long necks are joined by razors that are crescent-shaped and are engraved on people who hunt animals.

Around 600 BC. e. simple tombs in Central Italy are replaced by tombs with cameras (tombe a camera). This was the time of the highest prosperity of the country of the Etruscans, whose wealth favored the importation of works of art from the Eastern basin of the Mediterranean Sea to them. Middle Italy was flooded in waste and semi-eastern forms. We have already spoken above (see fig. 222) about the Cyprus shields and bowls from the tomb of Regolini-Galassi in Cera, now in the Gregorian Museum in the Vatican. The same style as on them, we see on the treasures from the tomb of Bernardini, in Cera, and from the tomb of del Duce in Vetulonia. The Etruscans learned to depict lions and panthers, sphinxes, vultures and other fabulous winged creatures, and also became acquainted with palmettes, weaving stripes and other ornaments of oriental origin. In many tombs there are vases of Corinthian style. Pure bronze and amber figurines, which are found in particularly large numbers in the tombs of Vetulonia, are pure Italian works with a noticeable oriental hue. But even in the tombs of Bologna, which still served as the repositories of the ashes of the burned dead, came across things in which the eastern influence is reflected even more. Ornaments on clay vessels are interrupted alternately by rows of shapeless figures of people or birds. Rosettes appeared next to the swastika, monkeys, snakes and sphinxes appeared next to the fish. The style of these earthen vessels is called later villan. Others call it the latest Bologna style, or the style of Arnoaldi (at the main place of finds of his works). It is possible that it arose, as Belau suggested, under the influence of Rhodes products. In Villanove itself a bronze handle was found in the form of a schematic figure of a naked woman, on which birds sit (fig. 462). Her head and arms, symmetrically raised up, have a spherical shape. With all the ugliness of this figure, its ready-made, self-confident craftsmanship is shown in its artistic and handicraft performance.

Fig. 462. Bronze handle of the later villan period. According to Görnes

The gravestone steles from the necropolis in Novilar, near Pesaro, are much earlier than the beginning of the 6th century BC. e. On the front side there are scrawled images of sea battles, almost as shapeless as the northern drawings carved on the rocks, and on the back side an ornament that, according to Von Duma, can be considered distorted here in eastern Italy by the revival of the Mycenaean style particle. .

While in Central Italy, around the 50th of the 6th century. BC e., the prehistoric era gives way to historical, so that Etrure art from 500 BC. e. and much later it causes on our side a special relationship to it, in Northern Italy the prehistoric epoch is still ongoing and creates in the region of the Illyrian Venets another distinctive art, widely spread northward beyond the Alps and southward to the Apennine Mountains. The center of this art was, apparently, Este.

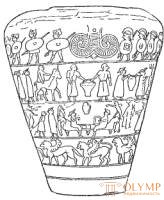

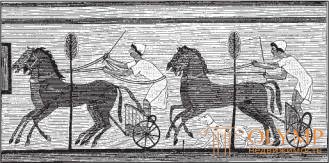

Fig. 463. Situla from Chertozy. By ranke

At least, most of his works were excavated here, mainly products made of sheet bronze were found, richly decorated with figured figures embossed on the back side with a hammer and gougers, and from the front they were usually finished with engraving contours and internal lines. Such drawings, mostly located in rows of stripes, are found on situlae buckets, lids, belt buckles and dagger sheaths.

The stripes on the Benvenuti sieve in the Baratela collection, in Este, are made up of strange figures. In the upper band are depicted people in wide, low hats, sitting in armchairs. In the middle lane, a creature that looks like a person, not a palmette, leads a dog on a rope. The remaining rows are filled with sphinxes, winged lions and other fantastic creatures. On the situation from Chertoza, near Bologna, now located in the museum of this city, we see friezes with images located in a larger order (Fig. 463). In the upper lane are foot and horse warriors, walking and riding one after the other. Two palmettes of purely oriental taste divide this strip into two parts. In the second lane, the sacrificial procession moves from left to right, the third shows musicians, hunters, villagers, and the bottom shows deer, lions and winged animals, going one after another from right to left. Empty spaces are filled with birds in the first and third lanes, rosettes in the second lane. At first glance it can be seen that the style of these works originated in general from the archaic Greek and that some particulars are made in this style, while others, such as hats and helmets on the depicted figures, are positively barbaric, in this case, Illyrian-Venetian; and the clumsiness of the forms representing proportions in the figures of animals are more correct than in the figures of people, and human faces are distinguished by strongly protruding noses, leave no doubt that we are confronted with a work of local art in a limited area of Northern Italy.

Products made of sheet bronze, decorated with friezes with images of only real or fantastic animals, are much more numerous than the works about which we have just spoken. But then, as the engraving on the aforementioned situations, despite all the ineptitude of the drawing, is notable for the confidence and conscientiousness of the techniques, work on many of these things is limited to a quick scratch or a dotted line.

We will return to the products of this style, then produced in the Alpine areas of modern Austria, when we talk about the Hallstatt style. But it is necessary now to mention the lid of a bucket from Hallstatt, the Vienna Court Museum. It depicts four four-legged animals, walking one after the other: a sphinx, a winged lion and two common deer. According to the rule often observed in this kind of art, animal herbivores are marked by the fact that they have branches in their mouths and parts of animals or humans in carnivores. In this figure, deer in the mouth have plants in the form of palmettes of an oriental character, and in the winged lion there is a thigh of some animal. All this, as Görnes said, "is depicted as beautifully and perfectly as possible as the work of the artistic group in question can be beautifully and perfectly." Of course, it is as far from true beauty and perfection as it is from completely barbarous primitiveness. In any case, the Etrure art of this pore seems stronger and more capable of development.

Just as the third century Hellenistic art. BC e. conquered Italy and the whole world, the Etrura gained dominance in all of Central Italy. Until that time, Rome had not yet had its own art. But the essence and techniques of Etrore art is not easy to determine. Often we imagine that we are dealing with peculiar forms of insignificant, coarse people oriented towards realism, whereas with a closer look they can reveal certain features of the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, which are familiar to us, by the way, and Greece. Some of the works that were previously considered the main examples of Etrore sculpture, such as the famous bronze chimera in the Florentine museum or the mythological and allegorical reliefs on bronze plaques in the Archaeological Cabinet in Perugia, are now recognized by all for Greek imported into Etruria. We have seen the mass of oriental metalwork, shields and bowls in which we recognize the products of Phoenician artisan craft (see fig. 461), lurking in the most ancient Etrure tombs with chambers; in the same way, we already know that tens and hundreds of thousands of painted Greek earthen vessels were preserved along with many other things of Greek origin in the somewhat later tombs of Etruria. In addition, it cannot be denied that, along with Greek art, the Phoenician influence on the development of Etrure was also influenced. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear that it was precisely ancient Greek art, which itself was under the influence of the East, especially the ancient Zionist art, was the teacher of Etrure. Kime (Kuma), the most northerly Ionian colony in southern Italy, was already very close to the borders of Central Italian culture, and the southern Italian greatcorers maintained trade relations between Etruria and the Greek metropolis to a much greater degree than we had hitherto assumed. For all that, Etrure art has a number of its own characteristic features. It developed some ideas that were completely alien to the views of the Greeks; it contains images belonging only to Etrure mythology, such as the demons of the underworld, armed with hammers; it remakes the Greek forms where it tries to assimilate them, unwittingly depriving the style of idealism and replacing it with a dry and rough love of reality, but at the same time remains in the diapers of archaism at a time when Greek art has already managed to throw off the last of its bonds.

Monuments of Etrore architecture preserved a little. Within the walls of the cities of ancient Etruria, erect on its mountains, we can trace all the steps of the cyclopean and regular polygonal masonry, the wrong and correct layering of the horizontal rows of plates. The best examples of regular polygonal masonry are the walls of the Goat and Preneste (Palestrina). Incorrect layering of slabs we find, for example, in the walls of Fezoul (Fiesole), Perussia (Perugia), Volaterra (Volterra), Cortona and Vetulonia. The correct layering of the plates, which was distinguished in Etruria usually by the fact that the plates hewn from four sides alternately with their long rectangular and short square sides, are found in Falerias and Ardea, as well as in the oldest parts of the walls of Rome itself. Noack suggested that this method of masonry was borrowed in Central Italy from a somewhat earlier Greek manner of building walls and that therefore none of the Etrure walls with horizontal masonry were erected before the V century BC. e. Особенной заслугой этрусков считалось то, что они прежде всех в Европе стали употреблять настоящий свод, сложенный из клинообразно отесанных камней. Их считали даже изобретателями свода.

Fig. 464. Каменный свод камеры над источником в Тускулуме. По Коенину

Теперь, когда нам известно, что искусство сооружать своды существовало на Дальнем Востоке в течение уже многих веков, остаются только два вопроса: когда именно и каким путем это искусство проникло в Этрурию? Марта, в обстоятельном сочинении об этрурском искусстве предположил, что и в этом случае посредниками были финикийцы. Однако после исследований Ноака становится более вероятным, что греки были учителями этрусков и в отношении сооружения сводов. Мы уже видели (см. рис. 442), что древнейшие греческие своды в городских стенах Акарнании относятся к V столетию до н. э., а к более древней поре нельзя отнести ни один из клиновидных сводов Этрурии. Громадная Cloaca Maxima в Риме с ее прекрасным сводом и триумфальная арка в Вольтерре с тремя головами на ее начальных камнях и замковом камне в нынешнем их виде должны быть отнесены не дальше как к эллинистической эпохе.

Но местное зодчество в Древней Этрурии прибегало к сводам также редко, как и искусство Греции. Кроме сточных каналов, каковы, например, каналы Марты близ Грависк и Cloaca Maxima в Риме, свод, с одной стороны, встречается лишь в позднейших гробницах, какова, например, Пифагорова гробница в Корнето, с другой стороны, в арках ворот, каковы арки в городских стенах в Волатеррах, Фалериях, Тарквиниях, Фелузах, и во входах некоторых гробниц Перузии, Кортоны и Клузиума (Кьюзи). В подготовительных формах и здесь нет недостатка. Ложный свод, образованный выступами верхних плит над нижними, встречается во многих гробницах, например, в гробнице Реголини-Галасси в Цере (Черветери); затем мы находим готически стрельчатый свод в известном сооружении над источником в Тускулуме, в Альбанских горах (рис. 464) и в капитолийской колодезной камере, впоследствии перестроенной, в так называемом Туллиануме, в Риме. Гробница Кампана, в Вейях, крыта ложным сводом другого рода: он вплоть до замыкающего камня образуется выступами плит друг над другом, но этот камень имеет в разрезе клиновидную форму, хотя, конечно, не играет роли настоящего, скрепляющего свод замка.

About Etrura architecture give us the concept mainly cemeteries (necropolis), which, occupying vast spaces, mark the location of the former main centers of the country. No people, except the Egyptians, did not treat with such respect for the burial places of their dead, like the Etruscans. Their tombs represent imitations of dwellings. Where it was possible, they were carved into the rocks; in other places they were covered with false or real ducts; often they were quadrangular structures of slabs, such as, for example, in Orvieto, or earth mounds (tumuli) on a round, simply profiled base, as, for example, in Montarozzi, near Cornetto; however, where they are arranged in natural rock, such as, for example, in the necropolises near Viterbo, the entrance to them is often decorated in the form of an artistically decorated facade carved into the rock.

Fig. 465. The plan of the burial chamber in Cerveteri. According to Koenin

Among the most enormous of the tombs with an earthen mound, preserved in Etruria, belongs to Cucumella, near Vulci. According to the descriptions of ancient authors, the tomb of Porsena consisted of five pyramidal towers on a quadrangular foot, four of which were in the corners, and the fifth - in the middle. The late Roman Hellenic descendant of such a device can be considered the so-called tomb of the Horatii and Curiatii in Albano, with its five cones on a square base. From the facades of tombs carved into the rocks in the necropolises near Viterbo, the facades in Castel d'Asso are remarkable for their heavy, three-piece cornices, while the tomb in Norquía has a facade similar to the facade of a Doric temple (with denticles over triglyphs).

Inside, the Etrure tombs are even more curious than the outside. Cameras in them were arranged on the model of living rooms. The dead, or their sarcophagi, or urns with their ashes were placed on benches near the walls, or in niches like alcoves, and they were abundantly surrounded by various household utensils. The doors, real and false, were framed by platbands that had protrusions in the upper part to the side, right and left (Fig. 465). In one of the tombs in Cherveteri carved into the rock beautifully shaped seats. The roof on the inside was an imitation of the wooden roofs of the Etrura houses, the appearance of which gives us the concept of some ash bins. The pillars of the ceiling were pillars, such as, for example, in Cerveteri, or pillars, as in Beaumarzo, and it is possible to distinguish beams cut into the rock and other details of the arrangement of wooden ceilings. Often there are also ceilings with real cassettes. One of the tombs at Cornetto gives us an idea of the internal form of the Etrore atrium described by Vitruvius (VI, 3) with its opening for light in the ceiling, not yet supported by columns; about the exterior of it, we can form an idea for one urn in the form of a house found in Chiusi and stored in the Florence Museum (Fig. 466). Another urn in the form of a house, in the same collection, proves that there were also houses with a gable and without a hole for light in the roof, which received lighting through wide windows in the side walls or through open galleries.

Fig. 466. Urn in the form of a house. By marta

Fig. 467. Column from Cucumella. Lubka

We can get acquainted with the architecture of the temples of the Etruscans by their description in Vitruvius (IV, 7). It is remarkable that this Roman writer recognized the special Etrure style of the temples; For their part, our archaeologists produce the Etrura, that is, the ancient Italian temple, not from a dwelling house, like a Greek, but from a templum, from a well-known, limited part of the firmament, on which augurs observed the flight of birds. In general, the Etrure temple is significantly different from the Greek one. On its high base leads stairs, arranged only with one, the front side. Having climbed this ladder, we enter first of all into a portico with a pediment supported by four columns and having two or more columns in its depth. Each of the three gaps between the columns of the facade leads to the entrance door to one of the three cellae, located side by side and dedicated to each one deity, and often to three deities. The average spacing between the columns and the average cella is wider than the side. The back wall of the whole building is deaf, but the front colonnade often continues along its sides. Since the entire upper part of the temple was usually built of wood and then richly painted, the columns were thin and slender, and the gaps between them were wide. The Etrure column, as described by Vitruvius, is only to some extent similar to those found, for example, in Kukumella, near Vulci (Fig. 467). The base of the latter consists of a thick round pillow, enclosed between two round plates. The core of the column is smooth. In the transition from it to the capitals, two rings go under the strongly tightened neck. The capital itself consists of a rather low Doric echin and a high abacus. But besides such columns in Etruria, there are also freely treated columns and columns that look like Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian; Likewise, the Etrura temples, excavated, for example, in Alatri, Civita Castellan, Falerii and Marzabotto, show that the architecture of ancient Italian temples did not hold so strictly on certain forms as one might think, based on the descriptions of Vitruvius.

The most famous of the Etruscan temples was the Temple of Jupiter on Capitol Hill in Rome. On the restoration of Martha, he differed from the normal type of temples in a colonnade, which surrounded him from three sides and had 6 columns in the front. According to Durm, the plan of this temple was not so simple, since in it the average cellar stood out and had, as well as side cella, its own portico in antis. The middle cella was dedicated to Jupiter, the lateral ones - one to Juno, the other to Minerva. The remains of the foundation of this temple are preserved in the garden of the German Embassy on the Capitol. Ancient writers reported that the general plan of this temple remained unchanged with all later restructuring. His original building, burnt down in 83 BC. e., built in 509 BC. e. That was the time when Rome changed the monarchical form of government to the republican one.

From that time on, Rome began to expand rapidly. Temples were erected one after another. The temple of Saturn on the capitol side of the forum was built in 497, the temple of Castor on the Palatine side of the forum - in 492. In 496, the temple of Ceres was built, known only from literary sources; in spite of all his pictorial and sculptural adornments by the Greeks of Gorgas and Damophil, this was, according to Vitruvius, a true Etrure church, "seemingly sprawled, flat, low and wide." His Greek sculptural decorations were a great novelty. Pliny the Elder clearly said that until then everything in Rome had an Etrore character.

In 390 BC. e. Rome was destroyed by the Gauls. But, having built again in the IV. from tufa and peperine and gradually penetrating the Hellenistic spirit, it generally retained the still ancient Italian appearance. At the beginning of the III. erected in Rome many buildings. Only from 302 to 290 BC. e. In this magnificently flourishing city, 8 new churches appeared. But the ruins of Roman buildings that have reached us from that time are too insignificant for any conclusions whatsoever.

The most impressive of all ancient Italian works of art are the remnants of Etrure wall painting, which survived for thousands of years in the silence and darkness of the tombs. Moreover, this Etruscan wall tomb painting, although it seems no more than a handicraft imitation of the perished above-ground art, belongs to the most valuable remnants of all ancient painting, the development of which we can trace in any way coherently only on these remnants, starting from the 6th century BC. down to the Hellenistic era.

Many tombs decorated with wall paintings are located in the necropolis of Tarquinius, the cities of Clusius, Ceres, Vulci and Orvieto. In the tombs of other cemeteries, wall paintings are found only occasionally. In technical terms, these paintings are, except for the Cerveteri terracotta tiles, real frescoes painted in crude lime, although in some places they are somewhat corrected with tempera. The background of the walls was usually white or yellowish. The paints in which the paintings appeared on this background were at first not numerous: dark brown, red, and yellow; then blue, gray, white, then red of various shades and, finally, green appeared; Later, the Etrure painters learned how to obtain different shades of transitional tones by mixing the main colors with each other. Striking in this painting is arbitrary, and sometimes unnatural, but adapted to the artificial illumination of underground premises coloring animals and plants.

The painting in the Etrur tombs of the most ancient times took for itself plots either from everyday life or from burial rites. Sometimes the paintings represent the position of a dead person on a stretcher, sometimes a funeral procession; even feasts, dances, athletic games, images of which are very common, or borrowed from funeral rites, or, just as we saw it in Egypt, reproduce the life that the relatives of the deceased wished him behind the grave. Soon completely etruric winged death deities, light and dark, began to appear. Actually, the god of the underworld was the Etrore Charon with a hammer in his hands, winged or uncovered. Plots drawn from Greek myths, began to be portrayed only in the Hellenistic era.

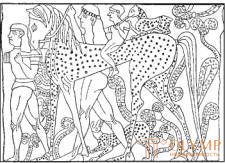

Fig. 468. Fresco in the Grotta Campana. By marta

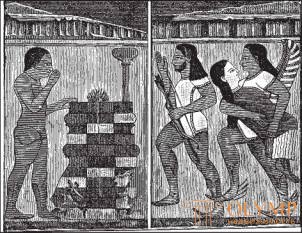

The stylistic development of this wall painting was obviously interconnected with Greek painting on vases. As we have seen, starting from VI. BC Oe., painted Greek vessels were imported into Etruria by the thousands. As a result, Etrure wall painting begins with the imitation of painting on the vases of the so-called Corinthian Greek style, flowing into the east. Wall painting in Grotta Campana, in Veii, with its pinto horses, sphinxes and panthers, with its patterns consisting of antennae of stylized flowers, buds and lotus stems, with its aversion from emptiness of angular spaces, with its three simple colors on yellowish-gray background, occurred precisely on this ground and belongs, probably by the end of VI century. (fig. 468). Then the influence of the most ancient Attic vase painting comes into force. The images in one tomb in Ceres, written on clay boards, of which six are in the Louvre Museum, in Paris, in appearance are approaching black-figure vase painting of a freer style. They belong to the beginning of the V century. The male figures are written, however, not with black paint on a red background, but red on a light one; the female body here is also painted white, and the profile position of all the figures, whose eyes are painted as they are en face, stands according to its technique at the same stage of development with Greek black-figure painting on vases; only figures with wide hips here are more rounded and squat; for example, a burial sacrifice with a winged demon carrying the dead woman in her arms is purely Etrure, as are the costumes of his figures (Fig. 469).

During the V century. freer archaic development occurs. The style of the paintings, which characterizes this time, is called tusko-archaic. Of course, these images are also based on the forms of Greek black-figure vase painting, but the content and feeling, in part also the types of faces and body shape, remain national-etrure. Of the paintings found in Cornetto, these include scenes of funeral rites in the Grotta del morto, still characterized by a small number of colors, hunting scenes, dances and games in the Grotta delle iscrizioni with their arbitrary multi-color tones, scenes of distribution of prizes in the Grotta del barone, glowing with bright colors , and lively images of military games in Grotta degli auguri. From the paintings discovered in the tombs of Chiusi, this includes scenes of athletic games in the Grotta della scimia.

Fig. 469. Frescoes from the tomb in Cera, Louvre Museum. By marta

The paintings in the “tomb of painted vaz”, in Cornetto, belong to more mature works in a more pronounced Greek taste. Greek vases with black figures are painted on the walls, similar to those that were immediately found in this tomb, and the same body movements of people in dances, the same as on Greek vases, it seems that the artist himself points to the source of his art.

For the tusko-archaic style follows the tusko-greek. The strict style of red-figured vase painting affects the Etrure wall painting. In the images of the Tusk-Greek style, Euphronius and Duris are recognized (see Fig. 337). But also with regard to the content, the national Etrure element begins to recede into the background. It is thought that the Etruscans of this time gradually Hellenized their customs, feasts, dances, games. Pictures of these groups, more abundant in colors (are red vermilion and green), still differ archaic stiffness of forms. They belong to the IV century. Among such paintings are, for example, images of dancing and music in Grotta del citaredo, open in Cornetto, with figures that still differ in the old strong development of their hips, scenes of horse lists with blue, green and red horses in the Grotta del corso delle bighe, dances and feasts in the Grotta del triclinio, in which the arbitrariness of colors is striking, but nevertheless, apparently consistent with the requirements of decorativeness. Among the paintings related here, discovered in 1866 in Tomba dei cacciatori, in Corneto, are something special: on a light background are depicted fishermen, hunters and bathers in a landscape setting with sea and rocks. The sea is marked with irregular wavy lines. On the rocks grow flowers and herbs. Birds are flying in the air. Since the drawing of figures, still archaic, does not allow us to attribute these paintings, reflecting in any case the more ancient stage of Greek development, further than to the 4th century, Reish also quite rightly cited them as proof that from the time of Apollodor and Zeuxis landscape background was not completely alien to Greek painting. The series of works under consideration ends with the paintings of the tomb of Tomba Casuccini, in Chiusi (fig. 470), the most ancient of the Etruro wall paintings in which we see the correct perspective image of the eyes. This proves that the wall painting also entered the road to complete freedom, laid by Etrure art only in the Hellenistic 3rd century. .

Fig. 470. Fresco from Tomba Casuccini, in chiusi

The people who filled the tombs of their dead with paintings that conveyed their earthly existence in colors, naturally, decorated their temples and dwellings with paintings as well. But along with the dwellings, their wall paintings also turned into ashes, and only from the stories of Pliny the Elder do we know that in his time ancient temple paintings still existed in Cera and that also in Rome as early as 500 BC. e. was in the temples of ancient Greek painting. Southern Italian Greeks Gorgas and Damofil at the same time decorated with their paintings the temple of Ceres in Rome. Over time, even noble Roman citizens began to devote themselves to painting. Fabius Piktor at the end of IV. BC e. painted the temple of the goddess Salus. We must assume that this painting was also imbued with the spirit of ancient rigor.

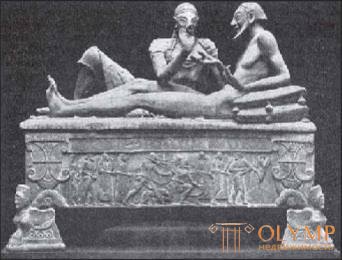

Fig. 471. The sarcophagus of Cerveteri. From the photo

Etrure sculpture has long been under the influence of Greek Ionian archaism. About 500 BC. e. The main material of sculpture was clay. Large terracotta groups sitting on the thrones of statues in the Capitoline temple of Jupiter in Rome were attributed to a certain Volkaniya (or Vulka) from Veiyev. Etrure large terracotta figures preserved mainly on the covers of sarcophagi. The most famous sculptures of this kind come from Cerveteri and are kept in the Louvre Museum in Paris and in the British Museum in London. The couple of the spouses represented as sitting on the bed is archaic and irregular in proportions, but very vital (fig. 471). В этой и ей подобных группах, так же как и в отдельных статуях, легко подметить все основные черты древнегреческого стиля, но столь же ясно различаем мы в них свойственное этрускам простое и верное понимание действительности.

Об этрурских бронзовых произведениях дают нам понятие не столько дошедшие до нас образцы, сколько указания, находимые в письменных источниках. Единственным произведением в своем роде остается до сего времени бронзовая волчица во Дворце деи Консерватори римского Капитолия (рис. 472). Волчица, кормящая своим молоком Ромула и Рема, – символ Рима

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)