By the beginning of the Hellenistic era, Rome, reaching the value of a great power, was already universally recognized as the ruler and capital of Italy. Then, over the next third century, gradually fell under the rule of Rome of all the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the cities of both ancient Greek and Hellenistic culture. But just as Rome conquered the Greek world, Greek art and culture conquered this city. Continuous flow flocked to the young capital of the world, to the banks of the Tiber, artistic treasures from Syracuse, Tarent, Corinth, Athens and many other conquered Greek cities, and at that time it was already ahead of these cities in relation to the construction of streets and bridges, water mains and sluices, in relation to her jewelery, she still studied everything from the Greeks. The Romans themselves were so aware of their dependence on the Greeks, both in literature and in the figurative arts, that attempts to attribute to them or the Etruscans any important part in the course of artistic development of late antiquity arouse strong doubt.

The artistic creativity of Italy in the Hellenistic centuries was gradually concentrated in Rome. When studying the Italian art of this epoch, along with Rome and its immediate and remote surroundings, are important in the north, as before, Etruria, and in the south of the city of Campania, covered in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD e. and re-digging from 1748, and between them - above all Pompey. Leveling Hellenism blotted out all local differences. The artists of Rome, Etruria and Pompeii in their works, so to speak, only expressed themselves in different dialects of the same universal language of art.

The Romans showed their independence most in architecture . In this regard, they have made artists the immediate need. With the construction of both temples and dwellings, they managed to preserve the ancient Italian basic forms, but clothed them in Greek attire. Roman architects learned first of all to feel like Hellenistic artists. If Antiochus Epiphanes (176-164 BC) invited the Roman architect Cossucius to Athens to build the temple of Zeus, built not in Italian but in Greek style, then this proves that the named Roman citizen was an artist with a Greek education . Much more important was the work of Greek architects on the banks of the Tiber. Already a century later, Metell, the winner of Pseudophilippe, invited the Greek Hermodore to Rome to immortalize the memory of his victory with the construction of the Greek, decorated with marble columns of the temple of Jupiter and the neighboring temple of Juno on the Champs de Mars. These two temples were covered by one common colonnade, the former of the large marble buildings surrounding Rome and the initial manifestation of Hellenization of Roman architecture.

At the same time, the Italian architects adopted from the builders of the Etrura and ancient Italian churches a predilection for the high base with the only staircase leading to it from the front side and the colonnade only on this side. Taking more and more resolutely the outline of the rectangle and turning one of its narrow sides into the canopy, they reduced the general plan of the temple more and more to the plan of the Greek. The Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders of the columns were used in Hellenistic processing, but in addition to them the fourth order, the Etruran, continued to be applied. On Italian soil can be traced a variety of mixed forms. Like the aforementioned Pergamon gallery (see fig. 444), the sarcophagus of L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus in the Vatican Museum, in Rome, has an Ionic eaves with denticules over the Doric frieze with triglyphs. The Corinthian-Doric temple in Paestum, with its general Italian character, represented the Doric entablature of a later epoch over the columns of a non-strict Corinthian style. In general, the Doric and Ancient Etruscan styles were sometimes mixed in the form of columns, which, with Doric proportions, had a smooth stem, a protruding ring on the neck and base, then similar to the Ionic-Attic, then refined to the degree of low tile. The Ionian capital, originally designed only to be looked at from the front, was often decorated, for uniformity of its appearance from all sides, with angular volutes protruding along the diagonal of the horizontal section of the capitals — an alteration that occurred in the Hellenistic time primarily in Italy (Fig. 475). In the Corinthian capitals, acanthic leaves became more and more soft and rounded, but only in the era of the empire, through connecting them with angular, protruding ionic volutes, the so-called composite capitals were formed (Fig. 476). Friezes often received an ornament consisting of several plastic leafy and fruit garlands, hanging in an arc-like way between the skulls of the bulls and accompanied by rosettes. That this important ornamental motif comes from Hellenistic Greece is proved, for example, by the marble altar of the theater in Athens, from which garlands consisting of masks are hung. This motive was further developed, apparently especially in Rome, on the friezes of temples and tombs of this time.

Fig. 475. South Italian Ionic capital with angular volutes. By Durmu

Fig. 476. Roman capital of a mixed style from the triumphal gates of Titus. By Baumeister

The oldest ruins of the temples of Rome, the ruins of the temple of the Great Mother of Mount Ida, founded in 203 BC. O., are only insignificant remnants, which, however, it can be seen that the rough peperinovye columns, some of whose particular parts received proper form only after plastering, were Corinthian order with an Italian arrangement of parts. The Temple of Apollo in Pompey stood among a rectangular courtyard surrounded by originally Ionic columns (17x9 columns), on a high base, which was led by an open staircase of 30 steps. The upper gallery surrounding his cella consisted of Corinthian columns (11x6); but this colonnade bordered only the back half of the temple, so the front part of the cella protruded from it forward in the form of a portico of Italian character. The Temple of Jupiter in Pompey, dating back to the beginning of the first century BC, was still of a completely Italian character, and only a few of its details had a Greek imprint. From 8025 Various temples have been preserved in Central Italy and Rome. The temple in Corey, in the Wola Mountains, was a Doric order, but built according to an Italian plan; its columns, which stood on the Ionic base plates, were covered with flutes only for the upper 2/3 of the trunk, and their capitals were thin and equipped with unusually low abacus, which cannot be called Doric in the strict sense of the word. The Ionian Order belongs to the Temple of Fortune Virilis in Rome, so-called at that time, and now bearing the name Matris matutae (Fig. 477), a pseudoperipter, which, at the same time, filled the masonry of the columns of its portico with masonry, was at the same time prosthetic. The walls of his cella from the outside are divided by semicolumns. The Corinthian Order owns two charming small round temples: in Rome, on the banks of the Tiber, and in Tivoli, in Anio (fig. 478); The round cella of the first was originally encircled by a crown of 20, and the same cella of the second by a crown of 18 columns. On the frieze of the Tivoli temple we find the above mentioned frieze with bull skulls, garlands and rosettes.

Fig. 477. Temple of Fortune Virilis (Matris matutae). With photos of Brodgy

Fig. 478. Round Temple in Tivoli. With photos of Brodgy

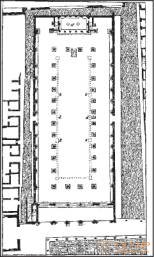

From civilian buildings in Rome, in connection with the forums, that is, rectangular, market squares, surrounded by magnificent colonnades, appear primarily basilica for commercial transactions and legal proceedings. These buildings, which received the Greek name (stoa basileios, or basilike, royal chamber), originating undoubtedly from the Hellenic East and having the meaning of "antique exchanges", can be best studied on Italian soil. Since they had to use them not only in warm weather, but also in winter, they were covered. Basilics are important in the history of architecture, especially because of them developed in the Hellenistic world a system of large indoor spaces, supported by columns. Usually the basilicas contained three naves, and in that case they often received illumination through windows arranged at the top of the walls of the middle nave, higher than the walls that bound the side naves. For the purposes of legal proceedings, a tribune was erected at the opposite side of the short side of the cella. Marcus Portia Cato erected the first basilica in Rome on his return from Greece in 184 (Basilica Porcia). However, the most ancient of basil, which can be restored with the help of their remains, is considered to be basil in Pompeii. Its side naves are of the same height as the central aisles, and the windows are arranged at the top of the walls of these naves. The middle nave was furnished on all four sides by 28 Corinthian columns, towering to the most gabled roof with two gables; the side naves probably had flat roofs like terraces. The walls of these naves were furnished on the inside with a bunk row of columns, below the Ionic, at the top of the Corinthian Order (fig. 479). In Rome, the basilica of Julius, the construction of Caesar (begun in 46 BC) was cleared. This marble building, dating back to the end of the republic, was a five-foot building. The middle space, not divided in all its height into parts, was surrounded on all four sides by a bunk double gallery, the lower floor of which had a ceiling in the form of a vault; the outer walls of this floor were not solid, but represented a series of open arches enclosed between Doric semi-columns.

Fig. 479. The plan of the basilica in Pompeii. According to Overbeck

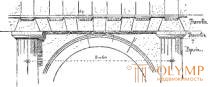

The oldest building in Rome, in which such a combination of arches and columns is found, bearing a straight entablature - a compound that soon became characteristic of Roman architecture and remains exemplary to our days, is the state archive, Tabularium, whose main facade occupied the slope of the Capitol above the forum (fig. 480). Twelve slender Doric semi-columns with small and unpretentious capitals stood at the sides of each of the 11 arches and, together with their low entablature, made up a frame around them; the upper tier of these arcades is not preserved, but it can be thought that it was of the Ionic style. This decorative system was hardly a Roman invention, but nothing like it has hitherto been found anywhere else in the Hellenistic East.

Fig. 480. Arch of Tabularia, framed by semi-columns in Rome. By Durmu

Theater buildings appeared in Rome in the Hellenistic era, but in 185 BC. e. the permanent theater that existed there was considered unnecessary and it was broken. The first stone theater in Rome, surrounded by gardens and colonnades, was built in 55 BC. e. Pompey. The Bolshoi Theater in Pompeii is built earlier this year. According to its original design, it belongs to pre-Hellenistic time, but its elevated stage, the back wall of which is the facade of a palace with three doors, was built only in August. We already know that for the first time from Rome the custom of playing plays was spread not in the so-called orchestra, but on a special elevated stage (see fig. 306).

This innovation is consistent with the conditions of Italian theatrical performances. For its part, the Italians' love of bloody spectacles - the persecution of people by beasts and the battles of gladiators that took place at first in the market squares, caused a special kind of buildings. Since in those cases when the performance was not in depicting poetic stories, but in a real, short and brutal fight, not on the stomach, but on death, and there was no need for any scene, it turned out to be convenient to take seats for the audience and that part theater, which is usually assigned to the stage. It is believed that Kai Kurion in 58 BC. e. connected two theatrical semicircles built of wood, which resulted in a new kind of orchestra that served as an arena for battle. But to this destination the oval arenas corresponded to even better round ones. Stone amphitheaters appeared in Campania earlier than in Rome; places for spectators were arranged in them on the massive lower floors and surrounded on all sides by an oblong arena. The aforementioned Kourion Theater could not serve as a model for such buildings. The oldest stone amphitheaters of Campania, such as, for example, the amphitheater of Pompeii, were built, perhaps, even before 58 BC. e.

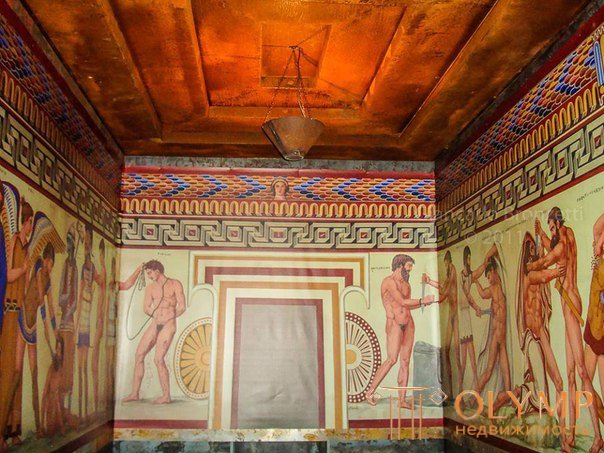

Fig. 481. A small term tepidarium on the Pompeii forum. With photos Alinari

A clear picture of the Roman public baths of the II century BC. e. give us the terms of the Stabian street in Pompeii, and about the later institutions of this kind - small terms on the forum of Pompeii, built a little later in 80 BC. e. The main parts of the male section of small therms are well preserved: a rectangular locker room, covered with a box-shaped vault, a round cold bath, under which a plaster frieze depicting horse lists stretches, and a warm bath (tepidarium) in which beautifully plastered and later renovated ceiling vault is supported on terracotta male figures (Telamon, Atlanta) with raised arms (Fig. 481), and a steam bath, also covered with a box-shaped vault, in which the wash basin was placed in a semicircular niche. Doric courtyard with columns, exedra (a niche for conversation) and vaulted corridors completed the device of this institution.

The most well-preserved monuments of republican Rome include some tombstones. Above, we have already mentioned the so-called tomb of the Horatii and Curiatii near Albano as the construction of the ancient Etrore style, although it belongs only to this epoch. By the I century BC. e. It refers to a small tombstone of Bibula in Rome, which, as E. Peters put it, “is an ancient tomb shaped like a house, refined in the spirit of the times and turned into a small temple”. The monumental tomb of Cecilia Metella on Via Appia, near Rome, dates back to this century. From her preserved massive, stacked cylinder plates, standing on a square base; the upper edge of the cylinder is decorated with the aforementioned frieze, composed of bull skulls, semicircular garlands and rosettes. The whole represented an alteration in the Roman spirit of the primitive burial mound (tumulus).

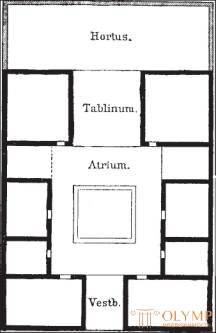

Fig. 482. The plan of an ordinary Roman house. By Durmu

More important than the tombs are for the history of art houses, which in Italy, as in Greece, were distinguished by the luxury and beauty of interior decoration and furnishings. However, Italian dwellings and in the Hellenistic era differed significantly from the Greek. Not a single house in Italy could do without an atrium, which in Greece was completely unknown (Fig. 482). Originally, the atriums were covered, with a floor, and the smoke of the hearth came out of them through the doors. An important step forward was the arrangement of a hole in the middle of the roof of the atrium, and the roof itself began to settle down with slopes to this hole, under which was a quadrangular basin, where rainwater flowed from the roof. Thus, the air and light access inside the house was provided. Vitruvius distinguished the Tuskan atrium, in which the sloping inward roof was supported only by horizontal beams, from the atrium with four columns supporting the inner corners of the roof, and this genus of the atrium was again distinguished from the Corinthian one, in which more columns were used to support the roof, as a result the atrium expanded and gained the character of a Greek courtyard with columns. The atrium was surrounded on all four sides of the room, between which a passage to the street (vestibulum) with the main door of the house was left. In the last two rooms, to the right and left of the person who entered the house, there was usually no front wall, so they presented themselves as wings (alae) atrium. Just opposite the entrance was a tablinum - the front room, open both in front and behind, and served as a communication between the front and rear sections of the house. Первоначальный итальянский дом состоял только из перечисленных помещений, имевших латинские названия, и из двора или сада (hortus), лежавшего позади tablinum; но эллинистическо-римский дом, как его описывал Витрувий, разросся за счет задней части в целый ряд покоев, окружавших греческий двор с колоннами, перистиль, и носивших греческие названия, например, exedrae (зал для бесед), oeci (зал для празднеств) и triclinia (столовые), располагавшиеся вначале вокруг атрия; некоторые потребности вызвали еще дальнейшие изменения и усложнения общего плана, главные части которого, однако, повторялись во всех домах. Дом знатного гражданина состоял собственно из одного этажа, хотя для добавочных комнат, жилья рабов и отдачи помещений внаймы, нередко с лицевой, уличной стороны дома надстраивался второй этаж. В конце республиканской эпохи появились в Риме многоэтажные дома с квартирами, сдававшимися внаем, и этого рода постройки уже в то время начали возрастать до такой высоты, что при императорах пришлось законом ограничить ее 70 футами.

Устройство итальянских жилых домов ясно показывает, как римляне, оски и самниты воспринимали проникавшие к ним греческие искусство и культуру. От особенностей своих домов, обусловленных складом семейного быта, они не отступали. Греческий двойной дом с отдельными помещениями для мужчин и женщин противоречил итальянской семейной жизни. Для римлянина, как и для жителя Помпеи, его атрий и tablinum с портретами предков был святыней, без которой он не мог обходиться; но увеличение числа комнат дома сообразно условиям эллинистического времяпрепровождения и образа жизни происходило уже по греческим образцам; художественная внешность, в которую в то время облекся итальянский дом, была перенята также от греческих городов Востока.

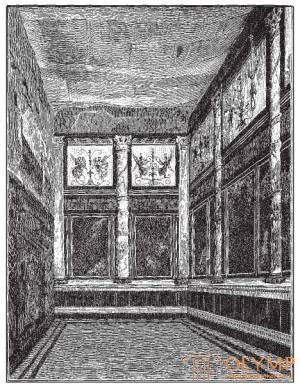

Fig. 483. Перистиль в доме Эпидия Сабина в Помпее. From the photo

Columns and entablature in residential buildings used forms elaborated by the architecture of the temples, but at the same time many liberties and violations of the established rules were allowed, just as is the case with the spoken language in relation to the literary language. Fantastic capitals of the Alexandrian character or arbitrarily invented type were at that time not uncommon in Roman and Pompeian private buildings. In Fig. 483, the second peristyle in the Epidius Sabine of Pompeii. Of course, houses of this kind, in their restored form, belong already to the times of the empire; but, even being in ruins, they give us an idea of the location, how rich the houses of Pompey were under the republic. The walls and pillars were at first brick or folded from local ashlar (tuff, travertine, peperine), and their artistic veneer consisted everywhere in painted plaster; even after the middle of I century. BC e. marble began to penetrate into Italy, some time passed before noble Romans began to allow themselves such luxury in their homes as marble columns and wall cladding with marble slabs. The speaker Krass (in 100 BC) was, apparently, the first Roman to decorate his house with marble columns. At the end of the era under consideration, Rome was already shining with its marble palaces, while in provincial cities, like Pompey, the use of this valuable material was limited to columns and some individual parts of the building.

Fig. 484. A room in the house of Libya on the Palatine in Rome

Plastering the walls remained a common thing both in Rome and in Pompeii. Comparing the changes in the artistic decoration of the plaster walls, opened in these cities, with the descriptions of Vitruvius (under the emperor Augustus), one can trace the history of the development of wall decorations in Italy. We have already said above that in this story, in our opinion, reflects the process of evolution that occurred before in the Hellenistic East.

The “ancient”, as Vitruvius called them, that is, the Hellenistic architects began in the 3rd century, and the Roman ones in the 2nd century BC. BC e., imitate marble cladding stucco plaster. Its specimens are preserved in Pompeii, in the basilica and the philistine houses, now known as Casa del Fauno and Casa di Sallustio. But already the walls of the Basilica of Pompeii testify that the marble facing, under which the plaster is forged here, was accompanied by the architectonic division of the walls into parts by means of semi-columns. This style of plaster walls, which Augustus Mau, the best expert on this branch of art, considers the first in time.

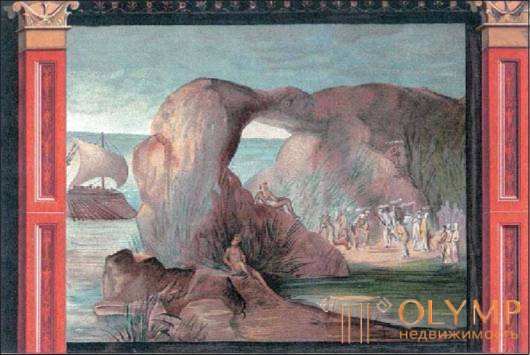

The second style, which came into use in Rome, is undoubtedly from 100 BC. e., and in Pompeii, which appeared in 80 BC. e. together with its settlement by the Romans under P. Sulla and practiced both in Rome and in it, up to the initial time of the empire, he renounced plastic decoration of plaster in favor of continuous painting the walls. But in the wall painting this style imitated, on the one hand, still marble facing, and on the other - luxurious architectural cutting, which, of course, allowed in particular a lot of free, new and arbitrary motifs, but was not so fantastic that not have the kind of "really existing" (Mau). The main difference of the second style from the first is that now the painting of the walls has become more resorted to paintings with figures and to landscape views. We find this in a house decorated with landscapes with scenes from the Odyssey, on the Esquiline Hill in Rome, as well as in the so-called Libyan house on the Palatine (Fig. 484) and on the walls of the house near the Farnezinsk villa stored in the Roman Term Museum. From the Pompeian houses it represents us, for example, the so-called Casa del Labirinto.

On the third style, referring to the first 75 years of the empire, and the fourth, which arose only from 50 AD. O., we will talk later.

But even with the republican greatness of Rome, the special art of decorating floors with patterns in the form of carpets was developed with the help of a mosaic of stones or glass alloys. The technique of the mosaic business from its very beginning (when the cement mass, usually painted red, was poured on a tightly rammed and leveled earthen floor and small pebbles were inserted into it, opus signinum) and we can trace it to Italy at that time to achieve perfection.

Painting in Italy in the considered period of time was in the closest connection with this development of the ornamentation of walls and floors. The surviving ancient paintings are mostly wall paintings, that is, as we believe, together with Otto Donner von Richter, in contrast to the opinion of Ernst Berger and others, belong to the category of fresco works, except for certain cases when paintings are inserted into the wall. Mosaic pictures also played an important role.

The frescoes of the Etrore tombs and houses of Rome and the cities of Campania, which were killed during the eruption of Vesuvius, together with the images on the vases, constitute the main part of all the material that has been preserved for studying the history of ancient painting. In 1873, Gelbig explained in detail that artistic painting of this era on Greek soil was Greek-Hellenistic, not only in the area from which it took its content, but also in its forms and methods of writing, and all the considerations that were at times given in denial of the views of Gelbig, turned out not to withstand criticism. Etrure painting of the time under consideration retained many of its local, Italian characteristics in the Hellenistic shell. Roughly realistic, non-Greek in spirit and technique, found among the monuments of Kampania’s painting, indicate that these works served other purposes than the goals of art. But one can argue about how the wall paintings of Rome and Campania allow for the opposite conclusion about the figured paintings of the great Greek painters on the boards. Of course, in dealing with this issue, only small paintings on the extensive walls can be taken into account, which seem to be obvious imitations of the pictures written on the boards. It must be assumed that the room painters of Rome and Pompeii, having passed more or less handicraft school, did not copy one or another easel picture of a famous master with precision. From the stock of their samples, they took only individual figures, groups, motives of movement and used them in accordance with the requirements of each case, both in terms of content and in a decorative attitude, connected them with other figures and groups, reduced or increased, associated with more or less. less processed background. As Trendelenburg proved, the requirements of decorativeness consisted primarily in that on equal parts of opposite walls, or on symmetrically located side fields of the same wall, scenes were written, corresponding to each other in the number and posture of the figures, according to their relation to the background and colors. That the individual motifs and figures of such paintings were indeed borrowed from known paintings or related to them, this is proved, for example, by the above-mentioned painting of the Neapolitan Museum, depicting the sacrifice of Iphigenia, transmitting the same degrees of grief what the animated figures Timanf in his famous painting (see Fig. 335); likewise, the repetition of the same scenes, such as Medea, Io and Argus, etc., often encountered in the paintings of Rome and Campania, is no doubt the existence of well-known patterns. No doubt, similar wall paintings were performed by painters of Hellenistic schools caught in Italy It goes without saying that these painters did not have at their hands samples brought from the East for images of each object of inanimate nature, each landscape and even each plot with figures, and changes in their style mainly concerned the development of architectural details and the cutting of painted walls into parts.

Fig. 485. Achilles, sacrificing the shadow of Patroclus. Fresco in the tomb of Francois in Vulci

As for the wall painting in the crypts of Etruria (see fig. 468-470), it went along the old road. Here, as before, there was no question of imitating easel paintings; wall painting continued to adhere to its original, primordial rules, was distributed evenly on a light background, did not care about its beautiful architectonic dismemberment.

However, the Etrure wall paintings of the Hellenistic era are very different from previous ones. All the turns and cuts of human figures are now reproduced easily and freely. Moral movements are transmitted not only by postures, but also by facial expressions. By the naturalness of colors, in which figures are drawn on a light background, often already developed modeling with the designation of light and shadows joins. Images and plots of Greek mythology begin to penetrate into the tomb chambers of Etruria, not yet completely displacing the ancient Etruscan demons. Greek light idealism is obviously mixed with realistic and gloomy ideas of Etrore fantasy, and he and these ideas appear directly next to each other.

The famous tomb with 9 chambers in Vulci, which received the name "Tomb of Francois" on behalf of the archaeologist who discovered it, refers to the initial pore of this development. In its various chambers scenes are drawn on the walls, taken from the Greek heroic epic. But in its quadrangular final premise we see on one wall an image of a real human sacrifice in all its coarse Etruscan realism, and on the other a symbolic human sacrifice presented in more ideal forms, namely, brought by Achilles before Troy to the shadow of Patroclus (Fig. 485). Etrure demons are mixed here to the heroes of the Greek epos, Achilles, Agamemnon and Ajax are indicated in the Etrur inscriptions in their Etrore names.

Golini’s tomb in Orvieto, with its dining room (objects of inanimate nature), a feast in the netherworld and a triumphal procession of the dead, abound in wonderful paintings of this style. The same stage of development belongs to the picture of the first chamber in Tomba dell'Orco, in Cornetto, with the terrible figure of the carrier into the underworld of Charon, gnashing his teeth, sharp-nosed, ferocious; the painting of the Hellenistic picture, located in the second chamber and depicting the underworld, is more free to receive its performance, but even more free, although the picture in the third chamber of this tomb, depicting Odyssey, popping Polyphemus’s eye, is more incoherent. Then in the wall paintings from the tombs found by the Countess Brus in Cornetho (Tarquinia), we no longer see anything Etrure. Tarquinia is a Roman provincial town. The style of the Hellenistic-Roman wall painting also prevails here.

Early Hellenistic painting on the vases of Etrura fabrication is also distinguished by certain national features. In one of the famous drawings relating to her, we see Ajax killing his prisoner, next to Charon, holding the hammer and waiting for his prey. The inscriptions in the figure are Etrure, the plot is Greek, the style represents an obvious mixture of Etrore and Greek elements.

The pictures on two sarcophagi found in Cornetto have a completely Hellenistic imprint. At the best of them, located in the Florentine Museum, on each of the four sides depicted the battle of the Amazons with the Greeks. The general arrangement of the figures in these scenes is as symmetrical as the movements of individual actors and groups are free; the background on the long sides is bluish, on the short ones black. The even bright colors of the paintings appear gracefully and freshly against this background. Etrure inscriptions prove the native origin of this work; but the artist who performed it was probably, like many of his comrades in Tarquinia, originally a Greek.

In the tombs of Rome also found ancient paintings that have some value. Fragments of large wall paintings, obtained in 1876 from one tomb on the Esquilino Hill and now kept in the Palazzo dei Conservatory in Rome, present plots from Roman history, arranged in strips one above the other and written on a white background. The commanders, conferring among themselves in the middle lane, in inscriptions in Roman letters are called Marie, Fannie and Quint Fabius. Although these paintings, as proved by Gelbig, are executed not earlier than the last decades of the 3rd c. BC Oe., however, they, if I may say so, speak the language of the most ancient Greek painting in a remake of the Italian dialect.

In the remnants of the decorative wall paintings in the Roman palaces of the time in question, Roman painting already appears to be quite Hellenistic. Since the first style did not produce paintings, and the third arose only together with the empire, it is obvious that here in front of us are the remnants of the beautiful wall painting of the second style.

Fig. 486. Odysseus in the underworld. Fresco from Esquilina

To the beginning of the stage of development in question, it is necessary to refer, according to Vitruvius, the Esquilinian landscapes with the scenes from Odyssey, which were mentioned above. The author of this essay, who published them in chromolithographs in 1877, then referred them to the time of Emperor Augustus, but now willingly joins the opinion of Mau, who finds that these paintings, judging by their performance, should be attributed to approximately 80 BC. n e. and that it is impossible to attribute them to the time of Emperor Trajan, as other researchers do. Apparently, they were, as is evident from the latest excavation reports, not at the same height with the eyes of the spectator, but on the upper part of the walls of the room with the vault, which is also indicated by the perspective of the pilasters that divide these paintings, and the small size of the Greek inscriptions. A continuous series of paintings of one wall has been preserved. We see before us a vast landscape, as it were, behind eight bright red pilasters, with great taste decorated with fantastic capitals and written so naturally that they give the impression of the real ones. Among this landscape, the scenes of the adventures of Ulysses described in the Odyssey among lestrigonov, in Circe and while traveling to the nether regions (Fig. 486) take place. All these scenes are arranged in the same order in which they are described in the poem, and are depicted extremely vividly and clearly in very small figures. These pictures, merging with one another, stretch like a panorama behind the red pilasters, completely independently of the division of the wall by these pilasters into parts. The fifth picture on the left, which, judging by its perspective, was medium on the wall, is architecturally prominent due to the fact that it depicts the Palace of Circe. Here, in the same picture, Odyssey and Circe appear twice, in different episodes following one after another - a technique to which the ancient artists continued to resort even after they began to depict the landscape space in certain frames within certain limits, but used this technique is less common than the artists of the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. Landscapes are written extensively, not without clear hints of atmospheric lighting effects. Especially good in this respect is the third picture on the left, depicting a blue sea bay, in which lestrigon destroy the ships of the Greeks, and the penultimate, representing the entrance to the abyss among the magnificent landscape, imbued with mood; it is difficult to find anything similar to these paintings in ancient painting. Painting techniques are purely modern in the then and present sense of the word. Free wide brush strokes lie next to each other, not merging among themselves, and the viewer gets the impression of real light and air.

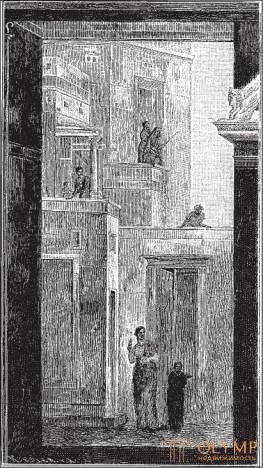

Fig. 487. Roman street. Fresco in the House of Libya on the Palatine in Rome

The frescoes in the so-called house of Libya or Germanicus on the Palatine, probably half a century younger than the described landscapes. Their decorative system gives us an idea of the later development of the second style. The architecture depicted here belongs to those that can only be realized in reality. In both side appendages of the table of this house, architectural painting dominates: Corinthian columns are depicted as if standing at some distance from the walls. In the table, as in the triclinia, the walls are decorated with paintings, of which some depict views, as if painted far through the openings of windows, others, obviously, imitate paintings written on the boards. Among the species in the distance belong the "sacred landscapes" in the triclinium and the Roman street scenes in the table; in the paintings of this second kind, we see high-rise, high-rise buildings facing the streets of Rome, rising in the form of terraces, with small balconies on columns and human figures (Fig. 487). Large pictures of the mythological content in the table, of which one shows the abduction of Io, and on the other the persecution of the nymph Galatei Polyphemus, make an impression written on the boards and inserted into

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)