Architecture

Of all the states founded in Europe by the Germans in the era of the great migration of peoples, the state of the Franks was the strongest and played the most important role in the implementation of cultural and political tasks of the time, and in the development of the visual arts, which led to new artistic forms content. The Frankish state, which at first occupied the west of modern Germany and northeastern France and gradually covered the whole of France and a significant part of Northern and Southern Germany, already dominated over the whole area of Roman provincial art in Merovingian time; in Gaul, this art - probably under direct Eastern Christian influence, which penetrated part through Ravenna, part, as Strigovsky believed, through Marseille, - already in Merovingian time, it became an ancient Christian art, but with a peculiar imprint (see above, p. 1) ; The legacy of this art of the Merovingian Frankish state also lived in the Carolingian era. Carolingian, as well as Ottonian, art was far from consciously creating on a new, German basis; on the contrary, the art of these epochs, essentially conservative, sought to continue the traditions of Christian antiquity. From this, the idea of the “Carolingian Renaissance” was born in science, which in fact was, in contrast to the Ottoman, more likely a relic of the old than “rebirth”. Those specific German elements that are contained in the Carolingian art, along with elements of the Hellenistic and Oriental, are perceived by them rather unconsciously; but these elements, undoubtedly existing, led to fruitful new growths. Whereas secular, court art held more antiquity, religious art, cultivated mainly in Benedictine monasteries, but also enjoyed the support and patronage of the Parisian and Aachenian courtyards, in many cases went its own way and developed, especially in architecture, a number of practical and ideological innovations that preceded the Romanesque style of the subsequent era. Although such a connoisseur of medieval architecture, like Degio, on the basis of the plans of many churches of the Carolingian era, called the Carolingian art already Romanesque, we consider, however, it is more convenient to consider both the Carolingian and Ottoman art, in view of the distinctly pronounced Doromanian department of art history. In the Carolingian period, in the center of the artistic movement stood Charlemagne, surrounded by his companions, among whom the most prominent were activities for the benefit of art Alcuin and Eingard. In Ottoman time, the great Saxon emperors, two Henry and three Otto played the role of patrons of art in the artistic life of Germany; but the highest ecclesiastical dignitaries, for example, Archbishop of Trier Egbert, Bishop of Constance Gebgard II, Bishop of Hildesheim Bernvard, Reichenau Abbot Vitigovo, and others were true adherents of artistic development at that time; also in the west of the Frankish state and in Burgundy, church architecture found considerable support in the person of prelates and monks. Cluny, where Abbé Ordon, having reformed the Benedictine order, founded the Cluny congregation in 930, had already become one of the centers of the spiritual and artistic movement, which received worldwide significance in the subsequent epoch.

Under the Merovingians, Northeastern France, with its capital, Paris, was the focus of Frankish artistic life. And under the Carolingians, as was especially proved by Hugo Graf, West Frankish church architecture stood at the head of the direction that was looking for new ways; but when, at the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne moved his residence from Paris to Aachen, the German part of the Frankish state began to come to the fore and artistically; At the same time, the prevalence of palace art caused the strengthening of a conservative, as we called it, direction, which gradually gave way to new trends.

Many first-class French and German scientists were involved in the architecture of the Carolingian-Ottonian era, relying in their research partly on literary sources, partly on the remnants of ancient buildings and on the newest excavations. Interesting are the major works of Viollet-le-Duk, Lasteiri, Schnaze, von Reber, Essenwein, B. Rill, von Degio and von Bezold, Borrmann and Neuvirth, and from the monographs - mainly the works of Georg Schaefer, Adam Golzinger, von Degio, Graf, Fr . - Yak. Schmidt, Schleinig and Effman.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

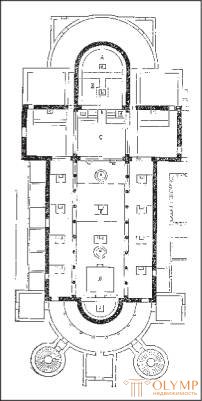

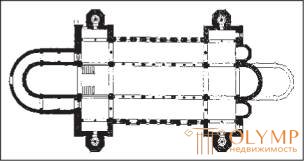

Fig. 89. Plan of St. Gallen abbey. By Degio and Bezold

Some of these features, as is well known, appeared in the West Francis churches of the Merovingian time; but in their full development, although not everywhere at the same time, they are encountered for the first time in the Carolingian architecture, with which we are familiar almost exclusively from literary sources compiled by Julius von Schlosser. These include, for example, the church of Saint-Denis Abbey near Paris, completed by perestroika in 775 by Charlemagne, and the famous Church of St. Riharia in the monastery of Centula (now Saint-Riquier) near Amiens, the construction of which began in 793. These churches had a cross-shaped view and already fully developed double choir. The Carolingian church, built in the IX century on the site of the basilica of St.. Martina on Tour, anticipated the Romanesque style with other architectural features: according to de Lasteira, she already had a choir with a crown of chapels and, in addition to the three eastern towers, two more towers on the sides of the western facade.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

Fig. 90. The capital of the column from the church of Sts. Justina. From the photo of Nab

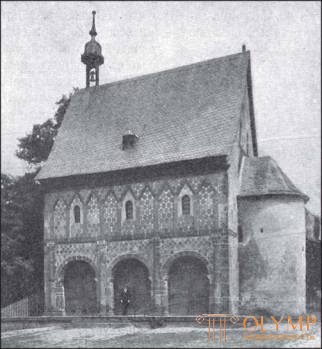

Fig. 91. Gate to the narthex of the monastery church in Lorsch. From the photo of Nab

Partly preserved are two small basilicas, founded by Eingard, the historian of Charlemagne, not alien to art: in Steinbach, near Michelstadt, 827, and in Seligenstadt, 828. They resembled the basilica of St. Michael on the Holy Mountain, near Heidelberg, founded in 883. All these churches, apparently, had a plan in the form of T, an atrium similar to that of the ancient Christian basilicas, and pillars instead of columns. Of the basilic columns to the temples of the same kind, the Church of St., preserved in its essential parts. Justina (fig. 90) in Hechst am Main, built around 840; it is possible that the church of the Corvey Monastery on Weser, a branch monastery of the famous West Franca monastery of Corby, rebuilt in 844, was also a column basilica; this is indicated by four Corinthian columns of the western part of the building erected around 1000 - the columns, which, as proved by Nordhoff, are the only remnants of the Carolingian church. Another ancient church in Lorsch (Hesse) on Bergstrasse, consecrated in 774 in the presence of Charlemagne. Only the gate of the narthex was preserved from it, perhaps even erected a little later (Fig. 91); but this small, elegant structure gives us - precisely because it has been preserved - a clearer concept of the forms of Carolingian architecture than all historical evidence. Three low arches of this gate are flanked by four smooth semi-columns with Roman composite capitals (Fig. 92). The low wall above the spans, with three semicircular windows at the top, is divided by ten barbaric, resembling cannelled Ionic pilasters, connected to one another by triangular bridges instead of arches. The cornice over the composite capitals of the semi-columns is decorated with a row of low and wide standing leaves of acantha. The inconspicuous crowning eaves lie on the toothed consoles. The entire surface of the wall is covered with a pattern like a carpet made up of white and red stones, as we saw in earlier Merovingian buildings. Roman-Hellenistic, Oriental and Frankish elements are mixed in the architecture of this gate, but the Roman-style beginnings are almost completely absent. Lorsh Gate is still quite an ancient Christian building. However, the architect who built them somewhat sinned in proportions, and in facing the walls and zigzags above the pilasters, he conformed to the national taste, which could also be independent of Far Eastern influences. The church itself, which has long been destroyed, must be imagined as a three-nave basilica with a flat surface, without a transept. The original plan of the Savior’s Church in Verdun on Ruhr, founded in 799, is in favor of such a reconstruction. Ludger, but completed only in 875. Effman's research has established that it was also a three-nave basilica with a flat cover and no transverse nave. Apparently, it was the oldest of the German churches, where in the middle nave the columns alternated with pillars.

Fig. 92. Composite capital of the Lorsh Narthex. From the photo of Nab

We know about the form of the other most important German basilicas of the Carolingian time exclusively from literary sources. Old Benedictine Church in Fulda (792–819), tomb of Sts. Boniface, represented in terms of a column basilica with a double choir and two crypts; Two choirs were also built in 831–850. Church of Gersfeld Abbey. Equally, the building, which formed the basis of the Cologne Cathedral, in the first half of the 9th century, apparently had Eastern and Western choirs. But also with respect to these East Frankish churches of the Carolingian era, it has not been proven that they have a cruciform shape.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

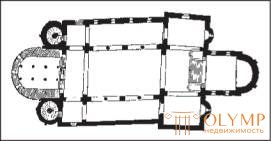

Fig. 93. Plan of the church in Gernrode, in the Harz. By Degio and Bezold

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

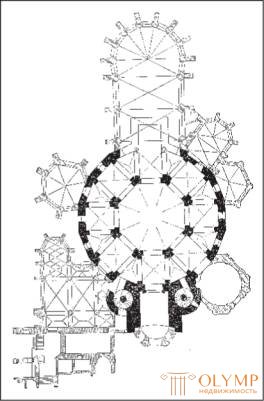

Fig. 94. Plan of the church of sv. Michael in Hildesheim. By Degio and Bezold

Fig. 95. The capital of the pillar from the church in Gernrode. Around the house

In Provence and Aquitaine, single-nave churches with Korobov arches are found as special forms, resembling similar northern Spanish buildings (see above, Vol. 2, II, 1). But even for this kind of churches, the years of their construction only from the last third of the XI century. become known with certainty.

Fig. 96. Capitals of the castle church and the church of Vipert in Quedlinburg. Around the house

Fig. 97. The capital of one of the most ancient (Bernvardovsky) columns of the church of Sts. Michael in Hildesheim. Around the house

Впрочем, и в немецком зодчестве в течение всего этого периода отдельные архитектурные формы в существенных своих чертах представляются еще дороманскими. Капители колонн по большей части напоминают коринфские, реже — ионические; аттические базы еще не имеют грифов (угловых листиков). Антаблемент над относящимися приблизительно к 844 г. колоннами в западной части церкви Корвейского монастыря — совершенно античный, с дентикулами и шнуром перлов. Колонны упомянутой выше хорошо сохранившейся церкви в Гернроде, оттоновского времени, увенчаны чашевидными капителями, которые усажены завивающимися вверху растительными стеблями и человеческими головами (рис. 95); одна из круглых башен этой церкви украшена снаружи пилястрами, которые, как в Лорше, соединены между собой не арками, а треугольными фронтонами. Капитель с перевернутым эхином, по терминологии Дегио — «грибовидная» капитель, встречающаяся в западной части крипты (997–1021) замковой церкви, в крипте церкви Виперта в Кведлинбурге (рис. 96), в Эссенском соборе и монастырской церкви в Вердене-на-Руре, является скорее искажением, чем преобразованием известных нам форм. Надставки, похожие на имноты, заимствованные, несомненно, из Равенны, мы находим на капителях колонн в ингель-хеймском дворце Карла Великого и в базилике св. Юстина в Гехсте (см. рис. 90). Романские, закругленные внизу кубовидные капители встречаются в Германии лишь изредка и, по исследованиям Дегио, прежде всего в западной части Эссенского собора, затем, в очень простой форме, но с античным шнуром перлов и дентикулами, на двух взятых из старого храма колоннах церкви св. Михаила в Хильдесхейме (см. рис. 95–97), аттические базы которых еще не имеют грифов.

If you look at the carolingian empire. They clearly reveal the whole Carolingian-Ottonian architecture with the ancient world.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

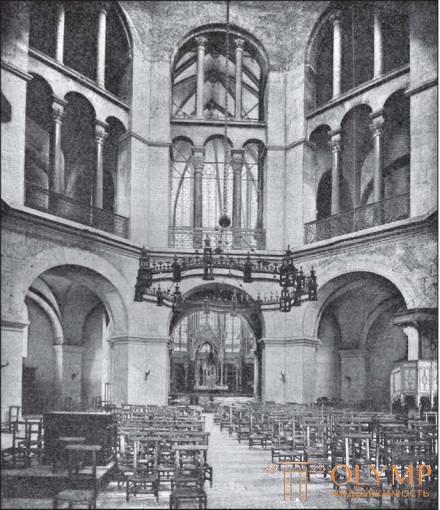

Play gameThe main monument to the intense construction activity of Charlemagne - built by Eingard in 796–804. Aachen Cathedral, the palace church of the emperor, intended to be his tomb. We have seen that, even in the early Christian time, the tombs were usually built according to a central plan. Aachen Cathedral in its basic forms is considered an imitation of the Church of St. Equ. Vitali. The main dimensions of both churches are approximately the same; both in the one and in the other, eight middle pillars are supported by arches on which a dome-topped dome with eight arched windows rests. However, according to Strigovsky, this basic architectural idea, which has long found expression in the art of the pre-Christian and ancient Christian East, could have acquired the right of citizenship in the empire of Charlemagne before the construction of the Aachen cathedral. Thanks to their active practice, Aachen architects could independently reach that sobriety, to the consistency and breadth of artistic design that amaze us in this temple. In any case, the individual architectural motifs of Aachen Cathedral have nothing to do with the church of Sts. Vitali. The middle octagon was in the lower low floor surrounded by a sixteen-square walk (fig. 98); because of this, in terms of a detour, alternately quadrangles, covered with cross vaults, and triangles, covered with three-tier arches, turned out to be alternately. The second floor rises high above the empores; its eight arches on the pillars, opening into an octagonal middle space, are twice as high as the arches of the lower floor. Above the octagonal drum rises an octahedral dome, without pandantos. All eaves - an extremely simple profile. The main decoration of the interior of the cathedral was a magnificent mosaic, not preserved to our time; however, in the cathedral there was no lack of architectural decorative elements. So, here were set magnificent columns, written out by Charlemagne the Great from Rome and Ravenna (Fig. 99). Each of the eight high arches, with which the upper floor opens into a middle space, is divided by a cross-beam in half; each half is decorated with the aforementioned pillars, of which the lower ones are interconnected and with the walls enclosing them arches with small semicircular arches, and the upper ones, modeled on the windows in Constantinople St. Sofia, abut right at the bend of the main arches. The balustrade of the upper gallery from the middle of the space is served by stylish bronze lattices; their patterns, consisting of beautifully interwoven columns and crossbars, are framed with pilasters in the ancient genus and rows of acanthic leaves and are seated with rosettes. These lattices, like simple, massive bronze doors, decorated only with lion heads, are poured in Aachen itself.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

Fig. 99. The interior of Aachen Cathedral. From a photo of Shtengel

This stately building excited a general surprise and served as a model for many later churches. The chapel of Nimwegen castle reached us, without retaining its original plan; church of sv. John in Luttych (978) rebuilt in the Baroque style; The hexagonal churches in Wimpfen and Metz (Fr.-Jak. Schmidt called them hexagonal basilica) are also not preserved because they were surrounded by a lower twelve-angle walk, as was the decimal baptism of the Cathedral of Worms; but the trilateral western choir of the Essen Cathedral (between 947 and 1000) is perfectly preserved, within which the three sides of the Aachen octagon with capitals of the Corinthian character are repeated. A strikingly faithful copy of the Aachen Cathedral is the interior — outside, albeit not sixteen-sided, but only eight-sided — the church in Ottmarsheim, in Alsace, built between 1000 and 1050. But the capitals of the columns here are no longer Corinthian, but cuboid, romance. However, it cannot be argued that all these buildings were certainly imitations of the Aachen court church; they could and directly go back to those samples as this last one. The church in Germigny des Prés (in the Loire department), built in 806 and unfortunately destroyed in 1463, was built completely independently of it. With her plan, which consisted of nine squares, with an elevated middle square, it resembled a Byzantine church in Rossano, in Lower Italy (see above, Vol. 2, II, 1). Its horseshoe-shaped arches and semicircular niches on each side were compared by Strigovsky with the corresponding elements of Armenian architecture (see books 1, II, 1). Finally, the often well-preserved small church of St. Michael in Fulda (820-822) (Fig. 100), although it belongs, like the Cathedral of Aachen, to the German main churches of the early Middle Ages, however, being round, with a ring-like circumference, can be attributed rather to the same type as the church St. Constance or of sv. Stephen in Rome (see Fig. 27). The inner circumferential wall of the upper floor is supported by eight columns with attic bases and low impost capitals. But the short middle column, which supports the crypt, is crowned with a coarse Ionic capital.

We can’t get a very clear idea about the palace buildings of Charlemagne in Aachen, Nimwegen and Ingelheim even after research by Reber, Clemen and others, the results of which are brought together by C. Simon.

Fig. 100. The interior of the church of sv. Michael in Fulda. With photos Molleguer

The Mainz Museum and Cathedral houses the remains of the Engelheim columns.

But in the descriptions of the residences of the Carolingian and Ottoman emperors, who were left by the chroniclers of these epochs, every now and then the magnificent structures richly decorated with antique columns, marble and precious metals are mentioned, and there is already one legend that Karl the Great is for his buildings in Aachen, and Otto the Great, back in 963, for the Magdeburg Cathedral (now coming to the ruins) were forced to carry heavy antique columns across the Alps, testifies to the unity of the artistic aspirations of the entire Carolingian-Otton century. These aspirations, of course, existed only in that upper stratum of society, for which Latin was the official language; folk architecture, from which no trace was preserved, was still wooden, and its ornamentation should be imagined as a derivative of Merovingian ribbon and animal ornamentation: in the manuscripts of that time, their mutual connection is obvious.

Painting

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameFor acquaintance with the history of Carolingian painting, the works of Fr. Leitshu, Lip. Janichek and Yul. von Schlossser, who collected tituli, preserved from that time, that is, the signatures under the paintings given in verses by the greatest scientists of the era. All these inscriptions and descriptions are in Latin. And in the artistic themes, as well as in the language of inscriptions, the ancient influence affected. We learn, for example, that the figures of the earth in the form of Cybele with a Grandsky crown (corona muralis) on the head or the heads of four winds with puffy cheeks played a prominent role in Carolingian painting, despite the direct prohibition of Charlemagne to depict these pagan incarnations of nature.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play game

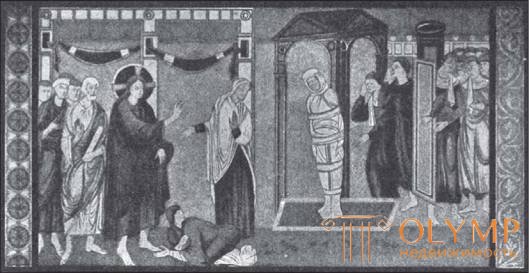

Fig. 101. The Resurrection of Lazarus. Fresco in the church of sv. George in Reichenau. According to Kraus

In Ottoman times, when Germany and France were already separate states, along with the increase in the number of churches, monumental church painting was becoming more common. From written monuments, we learn, for example, that in the church of Petershausen, near Constance, Old Testament scenes were depicted to the left of the entrance, New Testament scenes to the right; according to the most extensive title series that has come down to us, compiled around 1021 by the Benedictine monk Ekkehard IV, Mainz Cathedral was decorated with old and New Testament images with Old and New Testament images. From this, and perhaps even somewhat earlier time, was preserved in Germany, in the church of Sts. George in Oberzell, on the very island of Reichenau, from which, as we just saw, during the Carolingian era painters in St. Gallen were called, wall paintings, which are more valuable than all written evidence. Here we stand on solid ground. Not only the frescoes were preserved, but also the signatures under them. Unfortunately, the frescoes came from time to time in such a state that copies from them, published by Adler, Kraus and Borrmann, are almost more instructive than the originals themselves. The frescoes on the upper inner walls of the middle nave, painted between 985 and 990, have survived better than others; they are currently tightened on the canvas on which they are reproduced in copies. These murals depict the most important miracles of the Savior; on the south side in four panels arranged in pairs, in two rows, are presented: the Resurrection of Lazarus (fig. 101), the Healing of the Bleeding and the Resurrection of the daughter of Jairus, the Resurrection of the son of Nain's widow and the Healing of ten lepers; on the north side, also in four panels, - the expulsion of a demon near Gerasa, the Healing of a suffering water sickness, the taming of the sea storm and the Healing of the blind child. In addition, in the gaps of the windows there are images of the apostles, restored in the Gothic era, and below, between the arches, - round medallions with sculpted figures of the prophets. Eight main frescoes are bordered on the top and bottom by strips of luxurious, intricately intertwined and developed prospectively meander of late antique style, and from the sides - borders, ornaments of which are partly antique in nature (distorted curls of acantha and strip of rosettes), also partially transform into medieval forms. Biblical scenes found in ancient Christian frescoes and mosaics are more developed and abundant in figures. The scenes of healing the blind and the suffering of water-sickness are arranged relatively calmly and smoothly. The resurrection of the Nainsky youth and the Exile are confused with great drama. There is no mention of the depth of the background, although in the design of buildings one can sometimes notice attempts to create perspectives in the late antique spirit. Antique clothes. Christ is depicted as a beardless youth. The proportions of the figures are wrong, the shape of the body is skinny, and the gestures are completely unnatural. At the very first glance at the pictures, horizontal color stripes against their background are striking: dark blue at the top, greenish blue in the middle, brown at the bottom. The explanation of these bands is most natural to look for in that the artist did not understand the best examples that he used and in which the blue of the sky gradually grew pale downwards, and the color of the earth gradually turned into the tone of the sky.

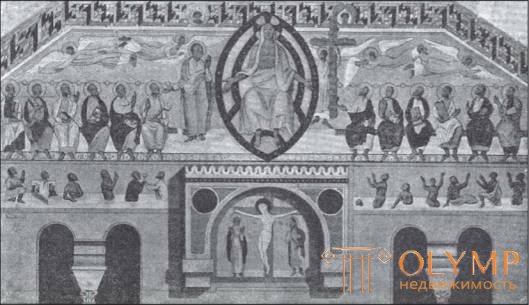

That this series of compositions is not a Reichenau invention, but should be viewed as a continuation of early Christian art, is ingeniously proved by Schmarsov on the basis of their location. The characteristic features of Byzantine-Greek painting are as invisible here as the direct influence of the monastery of Monte Cassino, a hotbed of Benedictine art. But if the more ancient Christian wall paintings were preserved in Gaul and Germany, we would perhaps be able to determine the transitional steps to this pictorial style, which in general is wild and ancient. The same can be said about the frescoes on the outer side of the western wall, which are now almost completely dead, despite the fact that they are protected by a protrusion of the wall. Below, in the middle niche, is depicted the crucified Christ with the Mother of God and the Apostle John standing at the cross; at the top the entire width of the wall is occupied by the oldest monumental image of the Last Judgment to the north of the Alps (fig. 102). In the middle, a beardless Savior sits on the throne, surrounded by an almond-shaped nimbus (mandorla); beside him, on the right, stands the Mother of God, on the left, an angel with a large cross. Below, twelve apostles sit in long straight benches in various poses, six on each side. In the frieze, beneath them, are depicted opening graves with dead men emerging from them, symmetrically distributed on both sides. Here is the moment preceding the Court: there are still no hellish torments or the bliss of the righteous on the scene. The composition, which in general is not devoid of solemnity and grandeur, reflected the expectation of the end of the world, which made the hearts of all around 1000 tremble. The upper border again forms a magnificent, intricately intertwining meander with two round medallions inserted into it from one side of the other on the other side, which depict the heads of ancient astral deities - the sun and the moon.

Fig. 102. The Last Judgment. Fresco in the church of sv. George in Oberzell. According to Janicek

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.9 people play!

Play gameVery close to the Oberzellsky frescoes in the choir of the choir of St. Sylvester in Goldbach, near Iberlingen, on Lake Constance. They were cleared of plaster that hid them only in 1899 and published in 1902 by F.-K. Kraus. On the eastern, northern and southern walls of the choir are four sedentary figures of the apostles. Among them, probably, Christ sat here, the Judge of the world, but His image was not preserved. Separate panels, as in Oberzella, are bordered on the top and bottom by bands of a meander. Due to the fact that

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)