Late autumn of Roman-Hellenistic art suddenly became the spring of Christian art. The new art was generated by the spiritual movement and therefore sought to speak not to the senses, but to the spirit; but the love for the beautiful inherent in the ancient world was still strong enough for the artistic reworking of new ideas and even for a part to translate them into new forms, and if just in the architecture of the first three centuries of Christianity, centuries of martyrdom, the artistic power of the new religion was manifested only in the closely defined limits This is primarily due to the persecution that prevented the emergence of Christian buildings or threatened them with destruction.

As Christian communities grew and worship developed, the need for Christian churches also gradually grew. The Christians of the first centuries gathered for prayer, usually in the homes of their wealthy co-religionists. But already in the II. private dwellings were not always roomy enough for rapidly expanding communities; Indeed, literary sources leave no doubt that already at this time in certain areas (mainly in Asia Minor), Christians built special buildings for prayer meetings. It is even possible, as Strigovsky asserted, that some of the Asia Minor and Syrian basilica and domed churches belong to the third century architectural works; but not one of the Christian churches that have come down to us can prove its appearance in the pre-Constantine epoch.

But in a significant amount the ancient Christian burial structures (cemetrias) have survived to our time. Respect for the graves, which was prescribed by the pagan laws, delivered a certain protection to the Christian dead. However, the above-ground cemeteries, which were opened in different localities, were not preserved as well and not in such numbers as the underground (catacombs), which the first Christians had decisively preferred everywhere where only the soil was dense enough for making these hypogees.

On the way from Palestine, their homeland, to Rome, relatively few tombs carved into hard rocks are open. In addition to the cruciform mountain tomb in Palmyra (about 259 g.), Which was previously attributed special importance in the development of cruciform churches, but which, of course, of pagan origin, like its remarkable painting, the ancient Christian catacombs in the Hellenistic East were preserved, for example, in Alexandria, Cyrene and on the island of Melos, and in the Hellenistic West - in Sicily, mainly in Syracuse and Naples. The Christian hypogues of this era are also found in Central Italy. But Rome has the most numerous and curious catacombs. Starting right behind the gates of the Eternal City and densely branching underground, they follow the direction of the large consular roads. The oldest and most remarkable Roman cemeteries (their names are often arbitrary) include: in the southern part of the city - the catacombs of Pretext and Callixt on Via Appia, the catacomb of Domitilla on Via Ardentina; in the northern part - the Priscilla catacomb on Via Salaria and the so-called Ostrian cemetery, with the catacomb of St. Agnes on Via Nomentana; in the western part - the catacomb of sv. Peter and Marcellinus on Via Labicana.

These underground cemeteries sometimes had external architectural parts. On the surface of the earth, there were open Cemetery chambers (cellae coemeteriales), opened by Marci de Rossi, whose purpose was to serve as a celebration of the memory of the dead, which was also permitted to Christians. As samples of such chambers, one can point to two square structures preserved above the Catacomb of Callixt, with semicircular protrusions (abshides) on three sides (Fig. 1). The fact that initially many catacombs had elevated monumental entrances, is indicated, for example, by the magnificent portal of the catacombs of Domitilla.

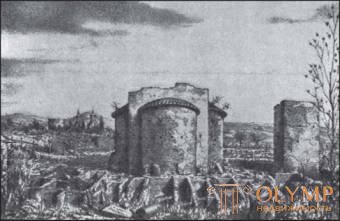

Underground corridors and catacomb chambers are often located in several tiers, dimly lit by vents made in the ceiling. The graves themselves were arranged in the walls, less often under the floor. Each individual grave, as a rule, consists of a shallow quadrangular niche (locula), the upper side of which is slightly lower towards the feet. Such a niche was covered with a plate decorated with epitaphs and symbolic religious images. For the burial of wealthier persons, semicircular niches with a flat back wall (arcosolia) were arranged in the wall. For noble families, whose members did not want to be separated even after death, the corridors expanded into burial chambers (cubicles, crypts), in which sarcophagi were placed or ordinary locules and arcosolias were arranged in the walls (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Cemeterial camera over the catacomb of Callixt in Rome. By de Rossi

Round cubicles are quite common in the Sicilian catacombs, in Rome, at least in the era under consideration, only quadrangular and irregularly shaped chambers are known. But we also find circular ceiling vaults in the Eternal City; similarly, the monotony of the chambers is sometimes broken by the semicircular apses. Their main decoration is wall painting. Mostly, columns and pilasters are also found in them. The so-called square crypt of sv. Januariya in the catacomb of Pretext in Rome produces, thanks to its marble facing, its pilasters and terracotta friezes, the impression of a true masterpiece of ancient Christian architecture; Significantly sized semi-columns also stand on the sides of niches in the extensive Ostorian cemetery chamber, which was divided into parts, which was usually cited by the Roman school and Kraus as the main example of the “catacomb churches” of that era.

Columns, semi-columns and pilasters of ancient Christian burial chambers are already quite noticeably shying away from the ancient nobility of forms. Thus, in one Kirensk cubicle we find short, clumsy, non-quantified columns with massive capitals that carry processes in the form of ionic volutes only at the corners; in one of the chambers of the Pretextat-Callixt catacomb in Rome (v), the capitals, which can already be hardly recognized as Corinthian, are formed by crowns of shapeless, vertically set leaves. But the fossors, who dug in these underground cemeteries in Rome, did not set out to create luxurious monuments of funerary architecture, similar to the ancient Egyptian or ancient Indian mountain tombs.

Fig. 2. Roman catacombs: a and v - chambers in Cemetery Pretextat; b - painting in Cemetery Priscilla (Jonah, spewed by a sea monster). By Perret

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)