Introduction Architecture

When the French king John the Good in 1363 transferred the duchy of Burgundy to his son Philip the Bold, who through marriage with the heir of the Flandres crown extended his possessions to the shores of the North Sea, a new powerful state was formed between France and Germany. Thanks to the wisdom, love of luxury and artistic taste of its dukes, for more than a century it has played a prominent role not only in politics, but also in all kinds of European art. The French and South German elements were tied together here especially firmly. Together with the French language, French architecture spread to the north of the Novo-Bourgogne state. Flanders, in turn, sent its sculptors and painters long ago already romanized Burgundy. In the first century of the era under consideration, the political unification of Burgundy and the Southern Netherlands was not yet complete, but the flow of artistic movement from Paris to the south-east and north-east directions had already prepared the ground for the fusion of art in both parts of the Burgundian state.

We have already seen how the Burgundian architecture took part in the initial development of the Gothic style. The Burgundian transitional style is represented in the front church of the Abbey of Cluny, erected in 1220 by the abbot Roland, to which the choir of the Lyon Cathedral and the ancient main parts of the Geneva Cathedral are similar in style. But the buildings of Burgundy from the middle of the 13th century are still works of transitional art, if only they, like the longitudinal buildings of the Nevers, Lyons and Vienne cathedrals, do not imitate the examples of the Paris school. The beautiful, wonderful, open porch church of Our Lady (Notre-Dame) in Dijon, completed in 1240, is still faithful in its plan to a coherent square system without circumventing the capella chapel; its choir ends with a half of a 10-gon, the windows have no sign of patterned bindings and do not yet occupy the entire width of the walls between the pilasters (Fig. 225), and the backwaters of the middle nave consist of columns of the transitional style. But the highly precisely designed system of vaults and buttresses of this church is quite Gothic. As for the buildings of the same type, you can point to the Auxerre Cathedral, the Church of Our Lady (Notre-Dame), in Semur, the Church of Sts. Petra in Geneva and the Cathedral of Lausanne (consecrated in 1275); the last two structures, however, possess richly dissected complex pillars. In the style of the "doctrinal late Gothic" of the XIV century, the Cathedral of Sts. Was built in Dijon. Bennigy is a bit boring, composed without imagination, but a clear and pleasant building.

Fig. 255. Constructive system of the longitudinal body of the Church of Our Lady (Notre-Dame) in Dijon. By Degio

In Burgundy, there was no shortage of secular buildings of the Gothic style. There are, for example, the vast hospital ward in Tonner (1293–1308) and the magnificent, luxuriously decorated palace of Philip the Bold in Dijon, whose “les beaux restes”, as Gonce put it, was later turned into a courthouse.

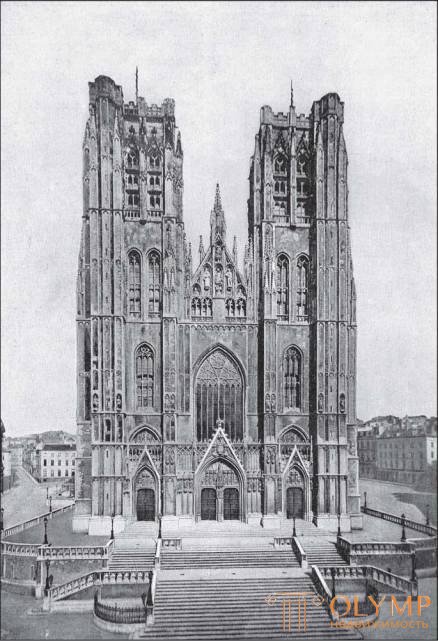

Church architecture in the Southern Netherlands until 1250 did not go beyond the framework of the transitional style. Church of sv. Quentin and St. Jacob in Tournai, the cathedral of sv. Martin in Aypern and the church in Lissevege are the best examples of this style. But even after 1250, the Belgian architects remained true to many details of the transitional style. True, the plan of the church gradually assimilated the French choral roundabout with the crown of the chapel, but the interior still preferred the short round columns; in the external architecture, the system of buttresses developed for high Gothic is not sufficiently consistent, and the windows are not wide enough; individual forms are also often still alien to the vigorous naturalism of French high Gothic. The most remarkable building is the Cathedral of Saint-Michel-e-Güdül in Brussels (fig. 256). His choir was completed in 1273, the longitudinal case with thick round columns was begun by construction only in 1350, a rather simply decorated facade with two towers without spiers was completed in the 15th century. In Bruges, the Church of Our Lady, whose tall, spire-crowned tower was completed in 1297, and the Church of the Savior, lined, as an exception, not in columns, but in complex pillars, belong to the 13th century and the 14th century, but in separate parts. - even the XV century. Among the most important monuments of the 14th century Dutch Gothic are the choir and the porch of the cathedral in Tournai. Started by building in the style of the XIV century, but ended in a more fantastic style of the XV century. the cathedrals in Mecheln and Leuven (the first was built from 1341, the second - from 1373) and the majestic seven-cathedral Antwerp Cathedral, whose picturesque choir with the ending in the form of half a decagon, was laid in 1352; the main part of this cathedral was rebuilt only in the next epoch.

Fig. 256. The western facade of the Cathedral of Saint-Michel-e-Güdül in Brussels. From the photo

Fig. 257. Cloth Hall in Eypern. From drawing

Plastics

The ancient burgundy church plastic was almost completely extinguished by 1250. The second half of the 13th century contained a rich, somewhat loosely-shaped plastic decoration of the Cathedral of Lausanne. For acquaintance with the 14th century Burgundian sculpture, the facade of the cathedral of St. Bennig in Dijon, if his rich sculptural decoration was not upholstered. But in the Netherlands provinces of Burgundy, many magnificent sculptural works of the XIV century remained. The images from the history of the creation of the world in the vestibule of the old cathedral, the group of the Annunciation on the wall of the Church of Sts. Magdalene and Kurtre - graceful reliefs on scenes from the life of the Blessed Virgin in the Church of Our Lady. The fact that we know from the documents the authors of a long series of statues of Flandre graphs and countesses who adorned the town hall, and even the names of the artists who were charged with painting these statues, does not give us information valuable for the history of art, since the statues themselves have not survived ( they were burned by the French in 1792). Fortunately, two magnificent bronze cast works of the 14th century survived in the Church of Our Lady in Tongerna, namely the choral lectern in the form of a large eagle and an elegant candlestick for Easter candles; the latter is marked 1372; both have the master's signature - Johan Jozes of Dinan. Dinan (see fig. 174), thus, was still famous for its cast bronze products.

Of the works of Dutch artists who worked in France and Burgundy, hardly anything survived in their homeland, in which Degan and Marshal agree with us. True, it is known that Andre Bonevo between 1374 and 1384. in Courtra, he directed the tombstone of Louis de Malus, the last earl of Flanders, in the Catherine Chapel of the Church of Our Lady and worked on the sculptural decoration of the choir itself; but these works were not finished, and the sculptures already completed were removed from the chapel. But in the capital of Burgundy, Dijon Philip the Bold, for sculptures in the Carthusian monastery founded in 1379, where his tomb was to be erected, attracted a number of Dutch artists; among them we find the Walloons Jean de Marville and Johann of Luttih, the South Germans Jacob de Bars (Baerse) from Dendermonde (Thurmond), the great Claus Sluter from the Dutch region of Meuse and his pupil and nephew Claus de Verve.

Jacob de Bars, for carved wooden altar folds of which Melchior Bruderlam wrote an image on the side doors, made two carved folds (a museum in Dijon), of which the first depicts Adoration of the Magi (9 figures), Crucifixion (20 figures) and the Coffin (8 figures), and the second - the Beheading of John the Baptist (6 figures), the Martyrdom of an unknown saint (7 figures), and the Temptation of St. Anthony (5 figures). These very vital forms of sculpture, richly decorated with gilding, were made around 1392 and represent a transition to realism of the fifteenth century. The lines of the folds still show the desire for perfect beauty, and the faces have already been fulfilled realistically, in the spirit of the new time. In artistic and historical terms, these works by Jacob de Bars are particularly interesting, as the earliest carved wooden ornaments of the altars, in which the large figures of the saints are crowded out with picturesquely painted smaller images.

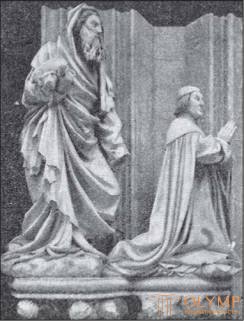

Fig. 258. Philip the Bold and John the Baptist. Statues of the portal of the Carthusian monastery in Dijon. With photos of Girodon

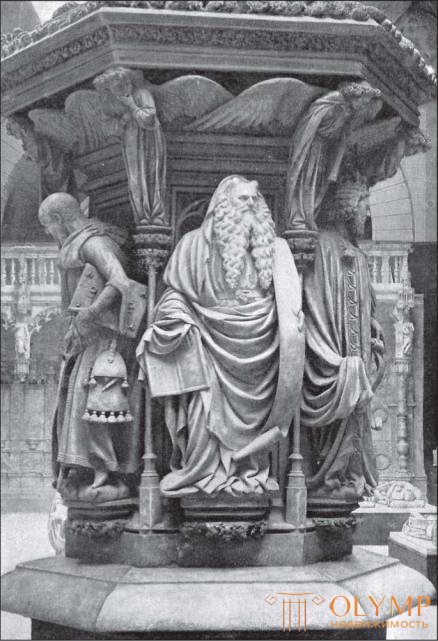

The participation of this master, whose independent works we will talk about later, appears to be more and more significant in the works of his great uncle as new documents are found. However, we consider it arbitrary to attribute to him, as Gones did, the figures of Zechariah, Daniel, and Jeremiah. In any case, the original models for all these figures were made by Sluter.

Fig. 259. Klaus Sluter. Well of Moses in Dijon. With photos of Girodon

Fig. 260. Tombstone of Philip the Bold in Dijon. From the photo

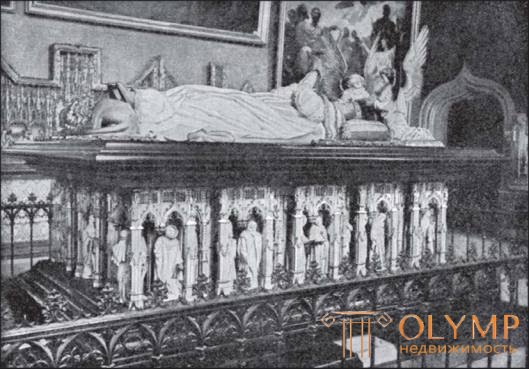

Finally, let us turn to the tombstone of Philip the Bold (Fig. 260), located in the Dijon Museum next to the monument to John the Fearless, set half a century later. Klaus Sluter completed at least the model of this monument; it is unbelievable that Jean de Marville carved a recumbent statue of the duke, as suggested by Gons; most of the whole monument undoubtedly belongs to the cutter of Klaus de Verve. On the sarcophagus of black marble, surrounded by 40 canopies of weeping monks and laity, surrounded by Gothic canopies, rests the white marble statue of the Duke with a crown on his head and with the palms of his hands folded together. At the head of the head - two small angels, kneeling, hold the helmet of the deceased; under his feet is a lion. The face and hands of the duke are treated quite individually. All the work is done with the greatest skill. Of the magnificent crying figures of this monument, only two can be considered as the handwritten works of Sluter, as a result of which our surprise over the talent de Verve increases. In any case, Klaus Sluter was a bold innovator, to whom Dijon owes his artistic fame. If we look at his works primarily as Dutch works of art, then we should not forget that it was the gravestone plastics that existed in Burgundy for a long time and that, in particular, the motif of weeping figures on the side walls of the sarcophagi known art (see t. 1, fig. 412), was equally well known, as pointed out by Kleinklaus, in Paris and Burgundy (the tomb of Val de Chou). Sluter was able to combine the old and his own, French and German, into one new whole, penetrated by the South German spirit. His works represent the highest level achieved by northern art in the XIII – XIV centuries, and at the same time largely anticipate the art of the next era.

Painting

Only after the separation of Burgundy from France and after its connection with the Southern Netherlands in the second half of the 14th century, painting flourished in the second half of the 14th century, mainly altar painting and miniatures. The history of the Burgundian-Dutch painters of that time, familiarity with which we owe to the archival research of Penshar, Degen, B. Pro and de Champo, shows what lively artistic intercourse existed between the courtyards of the four royal patrons of the time: the French king Carl the Wise and his brothers, the duke John of Berry, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and Louis of Anjou. Both in Paris and in Dijon the same artists worked; in both capitals we meet the Dutch masters together with the French. But, of course, since Flanders fell under Burgundian rule, Dutch artists began to play an even greater role in Dijon than in Paris. Some of these masters were of the Walloons; However, among the painters of Flemish origin were those who had French names, and one cannot say that Parisian art did not at all contribute to the development of Dutch national style in the form in which it began to appear from the 15th century. Even then, the German-Dutch miniatures, which can best be traced to the difference in style, differed from the clear in form and elegant French miniatures by greater realism and greater freshness of colors. Правда, в XIV столетии на нидерландскую живопись влияло еще — частью непосредственно, частью через Авиньон — итальянское искусство, в то время значительно ушедшее вперед, и история бургундско-нидерландской живописи в конце XIV столетия представляется во многих отношениях процессом освобождения от итальянского влияния в пользу дальнейшего развития национального художественного характера.

Как в Бургундии, так и в Нидерландах произведений стенной живописи и живописи на стекле XIII и XIV столетий сохранилось немного. Главным образом из письменных источников мы узнаем, что процветали там эти две отрасли монументального искусства, к которым присоединялась тканевая живопись аррасских ковровых фабрик. Перечисление остатков старинных фресок, которые в Нидерландах в 1850-х гг. очищены от покрывавшей их штукатурки, а местами и реставрированы (очень неудачно), предоставляем местным историкам искусства. Тем не менее мы должны отметить, что возникшие около 1300 г. гигантские изображения св. Христофора и Иоанна Крестителя на северной стене и небесного коронования Богоматери на южной стене трапезной городского госпиталя (Bijloke) в Генте отмечены совершенно условным, схематичным стилем эпохи, тогда как реставрированные остатки изображений фландрских графов на стенах Екатерининской капеллы в церкви Богоматери в Куртре, над которыми кроме Андре Боневё работал придворный живописец Людовика де Маля Жан де Гассельт, насколько еще можно судить об их стиле, отличаются уже большим реализмом, свойственным последней четверти XIV столетия.

Reliable paintings of de Bomets not preserved. Marville, Belletosis and Bruderlam wrote large altar images for the Carthusian monastery of Shanmole, near Dijon. These works greatly advanced the development of northern easel painting. Marville is credited with a round picture of the Louvre Museum, depicting the Most Holy Trinity with John the Baptist and the Mother of God near the departed Savior in rather strong, although not free from Italian influence forms; the background of the picture is golden. In the same style, the painting “The Martyrdom of St. Dionysius "in the Louvre Museum. It was probably started by Marville, but Beltoz is undoubtedly over. On the left is Christ the Comforter in front of the prison bars behind which a certain saint languishes; To the right is represented, very vital and dramatic, the beheading of the head of this saint. The background is still golden here. In their general character, both paintings belong to the 14th century. Pandan to the "Martyrdom of St. Dionysius "serves a painting in the Louvre Museum, depicting the life of St.. George The shapes of its figures are dense, modeled by grayish shadows, the background is golden. The painting was painted by Beltoz.

Dutch-Burgundy miniature painting in the course of its development is close to North French (see above), from which it differs only in rare cases more or less sharply. The Bible in the pictures of Philip the Bold, in the Paris National Library, was written around 1350 (the date in it — 1361 — was added later). The 2564 drawings in it, sustained in shades of gray and only slightly touched by colors, complement the biblical images with parallels from church life.

The success of the painting during the third quarter of the 14th century can be seen in the manuscript of the French translation of Blessed Augustine (1375; in the Brussels Library), whose significance for the history of the development of Dutch landscape painting was indicated by Kemmerer and Schubert-Soldern. Backgrounds of the landscape are still trying to conceal their promising impotence by artificially piling up of cliffs and painted hills of different colors; the proportions of individual parts of the landscape sin against perspective, and the distribution of light and shadows is still arbitrary. For all that, thanks to the inventiveness of the painter, the eyes of the spectator willingly succumb to illusion, and the general depiction of these rocks and hills, over which sharply drawn on the horizon of the tower and the roofs of certain localities, already gives us a strong idea of the landscape. The transition book, from the 14th to the 15th century, is the Book of Wonders of the World written for John the Fearless (the journey of Marco Polo, etc.) in the Paris National Library. In this manuscript, buildings and landscape plans, although a blue sky is already spread over them, testify to the artist’s lack of knowledge of the future; but the trees, as in the paintings of Bruderlam in Dijon, are well written, in fresh colors, despite the flaws in their drawing; to perfection still lacked artistic sense and understanding of nature.

It will be appropriate to mention the first steps of wood engraving (woodblock prints), that is, the art of making prints on paper from carved drawings on wood. As pointed out by Forrer, the art of stuffing drawings on fabrics with wooden stamps was known in ancient times. In the XIV century, printed fabrics of a special kind began to appear. The figured images were printed on fabrics with the help of carved wooden boards in order to copy drawings of altar curtains, such as Narbonne, or other drawings and paintings. In Burgundy, a piece of a similar board, cut in the last third of the 14th century, has been preserved; The main image on it is the Crucifixion. This board, located in the Prot meeting, in Macon (bois-Protat), was published by Boucher and gave rise to far-reaching, but only partially acceptable conclusions regarding the role of Burgundy and France in the development of woodcuts.

Some of the oldest woodcuts kept in the Prints Office of the Paris National Library, such as Christ on the Cross and the Lyon Madonna, for example, appear to belong to the 14th century and to Burgundy or neighboring countries; but it still does not prove that the art of woodcuts was invented in the field of the spread of the French language.

Be that as it may, even these early works of reproductive art testify to the versatility of the Burgundian artistic activity in the XIV century. At the end of this century, Dijon was one of the centers where the threads of all the artistic aspirations of Europe converged.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)