Introduction Architecture

Around the middle of the 13th century, Western Christianity began to free itself from the tutelage of the ancient world view, poorly understood and processed in the Byzantine or Romanesque-medieval spirit, and gradually rose to the heights of free research, direct observation of nature and independent artistic creation. In some areas, this new trend, which brought into the architecture the world domination of the Gothic style, and in the visual arts, which, although not quite successfully, aspired to the transition from style and mannerism to naturalism, manifested itself a century earlier. In the north of France around 1215, that is, when the University of Paris received its first statuses, the new spirit of the epoch was already vividly affected. However, if we take a look at the entire area of Western European cultural and artistic history, then, despite the arguments made by Gauston Steward Chamberlain, the middle of the XIII century will be more suitable than its beginning to draw one of those borders that the historian needs, but of course does not know in its continuous progress historical evolution.

Indeed, around the middle of the 13th century, both in the north and in the south of Europe, simultaneously with the full development of all medieval forces, a reaction against them began, taking place everywhere on the basis of the national language and national identity. Therefore, researchers such as Tode, Kraus, and Magni ranked this entire period, at least in Italy, where the new movement was most pronounced (Dante, Petrarch), already in the Renaissance, Renaissance, the beginning of which art historians had previously attributed only to XV century. Nevertheless, the gradual growth during this period of a correct outlook on nature and individual spiritual life, which went hand in hand with the awakened self-consciousness of peoples, should be viewed not as a rebirth, but as a consequence of medieval origins. All this spirit of the time, gradually discovered over a period of one and a half centuries (1250–1400), turns out to be nothing more than the highest development of the medieval spirit, and if we can talk about a return to the ancient forms, then in passing and within close limits.

Only after the crusades did Europe begin to live by its own interests, and if at first the national tendencies did not find a clear expression for themselves, then this was a direct consequence of the mixing of the peoples produced by the crusades. Roman church dogma, scholastic philosophy and the old feudal system remained a common connection between Western European nations. Monasticism and chivalry were still in full bloom, but everywhere the liberation of the people's soul came, and the isolation of the nationalities proceeded in parallel with the development of individualism.

Of the old medieval forces, monasticism still had a tremendous impact on art. But in contrast to the Benedictine orders and their offshoots, the mendicant orders of Dominicans and Franciscans, who themselves came out of the popular environment, who took their place, stood closer to the people and spoke in a language understandable to them. The fiery religious inspiration of the era of the Crusades was replaced by a concentrated, connected with the contemplation of nature, the religiosity that the Franciscan monks preached.

The philosophical system of scholasticism in the middle of the XIII century was developed in the writings of the Dominican Thomas Aquinas and the Franciscan Duns Scott, and at the same time was for the first time shaken from the inside. Roger Bacon in England and Albert the Great in Paris and Germany simultaneously pointed to the necessity of observing nature as the basis of empirical knowledge.

Finally, in state life, along with the old dynasties, numerous new sovereign houses were raised, owing their right to their own strength and the will of the townspeople, and along with the church and the feudal state, cities, especially in Italy, the Netherlands and Germany, became equal more independent, rich, flourishing, and often even complete independence from any other political power. Just in the middle of the 13th century, powerful associations of cities, such as the Hansa and the Rhine Union, emerged in Germany, in which the population enjoyed wealth and spiritual and artistic life flourished.

The builders and founders of temples and customers of works of art are still mostly spiritual dignitaries in episcopal residences and monasteries, as well as a few secular rulers who left a grateful memory of themselves in the history of art; but sometimes the city authorities or individual noble citizens already play this role. The execution of works of art, which in the previous epoch was mainly in the hands of the monks, is now being transferred to professional lay artists. In France in 1250, and in Germany around 1300, there were almost no other architects and bricklayers besides secular. In Italy, at least, the Dominican monasteries remained for quite a long time the official distributors of art, although it was in Italy that a number of great secular masters appeared, whose names are still on the lips of friends of art.

The whole artistic life was concentrated in the cities with their grand cathedrals, Franciscan and Dominican monasteries, which, in contrast to the old Benedictine monasteries, were built from the very beginning within the city. The population of the cities in a large part consisted of artisans and artists, and it was precisely in this era that professional corporations, shops and guilds, which brought together individual representatives of various crafts and arts, became very important. Near the workshops, at first, free construction partnerships existed, but they were gradually absorbed by the guilds of stonecutters, bricklayers and carpenters. Longer architecture and sculpture remained the lot of monasteries painting, especially the painting of miniatures. However, guilds and painters also appear during the period under review; their patron was considered the Evangelist Luke, who, according to legend, was himself a painter. Guilds of sv. Luke in Ghent, Bruges and Paris were the ancient society of St.. Luke in Florence (founded in 1349). Both in the north and in the south of Europe, the competition of individual masters of the workshop contributed to the bright manifestation of their individuality and the preservation of their names for posterity.

Great artworks originated during the one and a half centuries of the Gothic era in all Western countries and in all areas of art, but the greatest of them belong to architecture, in which the best works of sculpture and painting still played a supporting role. Although now, according to the development of urban life, along with princely castles, monasteries and churches, luxurious town halls, judicial buildings and residential houses were more often built, but the leading role in developing a style and inventing new forms belonged to church architecture more than before. Hardly ever before or after were temples of such dizzy heights as the Gothic cathedrals of the period under consideration were erected, and the fact that the builders of these cathedrals, starting to build them, were not embarrassed at the thought that neither they nor their closest descendants would live before the end of the building, testifies to their inspiring religious zeal and selflessness. Only a few cathedrals were started and completed during this Gothic period. Some of them have never been completed, others are completed only in the XIX century. It is these buildings, both by themselves and by their luxurious plastic and pictorial decorations, testify not only to the power of artistic creativity, but also - in their complete deviation from the usual forms - to the deep originality of this creativity, the seal of which marks all the works of that time. .

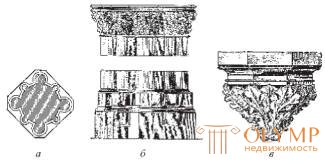

Fig. 237. Gothic complex pillars: a - cut; b - vertical projection; in - the gothic console with a deciduous ornament. Lubka

France, whose beautiful capital remained the beacon of the intellectual life of Europe, until it was eclipsed by the brilliance of a new life that began in Italy in the 14th century, was one of those countries where rulers throughout the Gothic era competed with the church authorities in their concerns about art. On the threshold of this epoch is Louis Saints (1226–1270), “French Pericles”, and at the end of it, Karl the Wise (1364–1380) and his brothers, who ruled the state instead of his unfortunate nephew, Charles VI, are historical persons worthy of the name patrons of french art.

In the north of France, architecture remained the bearer and educator of all higher artistic life, because it is the birthplace of the Gothic architectural style. However, it cannot be argued that the gothic style is essentially French in style. Undoubtedly, Degio is right, pointing out that the Gothic, although it grew up on French soil, is an international style for the whole of that era, rather than just a French style. Nevertheless, the merit of the north of France was due to the fact that it was here that the spirit of the time developed into a Gothic style, logically developed as a “cross-line, pointed and counterforce style”, full of lively artistic content.

Fig. 238. Gothic capitals with leaf ornament. Lubka

In the previous, third, book, we familiarized ourselves with the constructive system of this most constructive of all architectural styles, which turned wall surfaces into a series of giant windows, leaving only the stone frame of the backwaters and, in order not to clutter up the interior space, carrying counterforts and supporting arches to the outer sides of the building, On which lateral pressure of the arches rising to the sky was transferred. We talked about the ornamental forms of this style only in passing, because in the early gothic buildings they have not yet received a consistent development. Recall that, for example, in the Lansky and Parisian cathedrals, the middle nave rests on short round columns rather than on complex pillars, that in their capitals the acanthian motifs in the Corinthian spirit predominate and that their windows were initially devoid of patterned bindings. Therefore, we must, without adhering strictly to the French examples alone, dwell primarily on the ornamental forms of the developing Gothic.

In the churches of the mature Gothic style, the complex pillars (fig. 237 and 238) usually have a round central pillar, furnished with three-quarter service columns, on which the vaults rest. Four thicker (older) service columns support the longitudinal and transverse arches; from four more thin (younger) service columns the edges of the cross vaults rise upwards. With the increase in the number of edges, which with the further development of the style, multiplying and branching, form a star-shaped and mesh arches, the number of service columns also increases. The bases of these complex pillars are usually polygonal; in them only gentle horizontal grooves and shelves remind one more of the Attic base of the Romanesque style. The capital, bounded below, at the neck, by a ring, and above the abacus, is formed only by a slight cup-shaped bend of individual service columns. Wide and low, it no longer looks like a real capital, but rather gives the impression of a light, ornamented beam of belt leaves interrupting a vertical line. This purely Gothic deciduous decoration, which has a completely decorative character and no longer concealing, like a Corinthian basket, a constructive purpose (support of the entablature), also in form does not imitate the motifs of the Corinthian capitals, although sometimes it also contains acanth-like leaves. In the selection of local plant motifs, an awakened interest in observing nature is reflected; Oak, maple, grape, rose, burdock and ivy leaves are especially common, reproduced according to nature, although with strictly plastic stylization. The overall shape of the complex pillars of the best pores of the Gothic style is pure, pristine and chaste. Later, these pillars become partly burdened, partly not sufficiently dissected, and in some places again become simple rounded or octahedral.

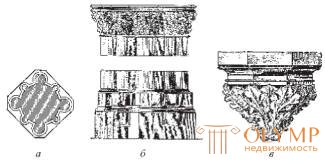

Fig. 239. Profiles of Gothic arches: A - Notre-Dame de Paris; b - the Cathedral of Narbonne; in - church of sv. Severin in Paris. Lubka

Rising from the complex pillars, the springs and ribs of the vaults, which in the Romanesque period had a simple quadrangular profile or, at the most, were decorated with round rollers, are more or less dissected from the very beginning in the Gothic style. At the same time, in early Gothic, this dismemberment is carried out by means of vykruzhek and round rollers, whereas in the higher Gothic style rollers get a pear-shaped-pointed profile, and in a later time fillets become flat and gentle. This gradual reshaping of the arches and ribs will become clear to us, as long as we compare the arches of the oldest parts of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris (1200–1230), the Narbonne Cathedral (circa 1340) and the Church of Sts. Severin (about 1400) in Paris (Fig. 239). Profiles of the heyday of the Gothic style in its own way no less elegant than the ancient Greek.

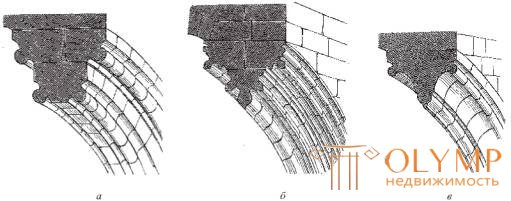

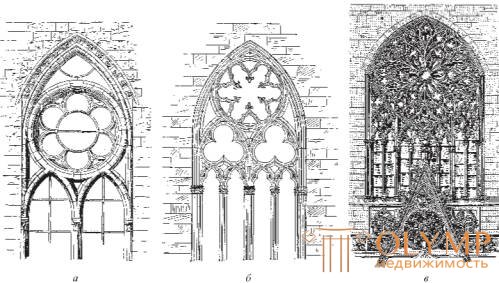

The dismemberment of wall surfaces is carried out mainly through giant windows, often occupying the entire height and width of individual spans. Only the main windows of the middle nave sometimes do not reach the bottom of the wall, which in this case is divided by triforium galleries; Triforiums can themselves pass into the windows, and their openings are then decorated, like real windows, with patterned bindings and openwork carvings. Slabs of window siding develop in a vertical direction, dividing the surface of huge archery windows into several parts; they consist of thin stone columns, initially rounded, in the form of columns, but soon receiving a Gothic profile, with fillets and ostrorebernymi rollers. Such crooks often also cover the walls of the facades and pillars with their filigree gratings. Openwork stone carving (Masswerk), which fills not only the archery top of windows, but often other surfaces, balustrades of galleries, etc., forms geometrical figures composed of various segments of an arc of a circle arranged in the form of clover leaves. According to the number of their arcuate sides, these figures are called trefoils, chetyrefoistniki, etc., and at first they are mostly inserted into round frames, but soon they are replaced by various, very fanciful, though always reduced to simple geometric shapes of the image. Fantasy, based here, as in Arabic ornamentation, on geometric tasks, provided a lot of room. Only during the transition to the next epoch, the geometric forms of the carved ornament turn into forms resembling a candle flame or a fish bubble and characterizing the late Gothic itself. If we compare the windows of the Reims, Amiens and Tours Cathedrals (Fig. 240), we can get a rough idea of this development.

Fig. 240. Gothic stone patterned bindings of window frames: a - in Reims Cathedral; b - in the Amiens Cathedral; in - in the Tours Cathedral. By Degio

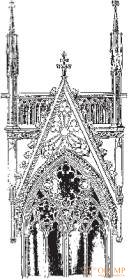

Fig. 241. Gothic vimperg and phials. From drawing

As for the exterior of the building, the portals kept the side walls and arching frames (archivolts) of the Romanesque time cut off by ledges; but in the Gothic epoch they usually, as later the windows, were crowned with high steep gables, imperial carvings decorated with openwork carvings (Fig. 241). Figures in the niches of the side walls of the portal were no longer placed on columns, but on the console, and canopies were arranged above them. Gothic profiles, of course, and here found a use for themselves everywhere.

High canopy canopies were abundantly used by the Gothic style in other places to decorate the exterior of the building, especially to crowning the buttresses; but at the same time, they often turned into deaf, only from the outside, decorated with false croakers, pointed turrets - phials (see fig. 241), in a large number of surrounding Gothic churches. All parts of the building stretch towards the sky. Карнизы также имеют срезанные углы, а по скошенному верхнему краю опорных арок, вимпергов и фронтонов лепятся, следуя один за другим, фигурные крючки, так называемые краббы, или кроссы (рис. 242), довершающие впечатление неутомимого стремления ввысь. Верхушки башен, вимпергов и фиалов увенчиваются флёронами, или крестоцветами (рис. 243), которые, будучи стилизованы в характере украшений, гармонично заканчивают собой элементы здания. Крыши всегда очень высоки. Односкатные крыши над боковыми нефами постепенно заменяются двускатными. Вдоль кровельных желобов тянутся балюстрады, украшенные узорчатыми горбылями и ажурной резьбой; водосточные трубы идут по верхнему краю опорных арок, над крышами боковых нефов, и оканчиваются у контрфорсов водометами, гаргулями, сделанными в виде фигур людей и животных, нередко крайне фантастичных.

Fig. 242. Gothic crabbe, or cross. From drawing

Fig. 243. Gothic crucifix. From drawing

Интерьер готического собора представляет собой полное, последовательное развитие принципов древнехристианской базилики. Три или пять нефов, к которым впоследствии иногда присоединялись, в виде шестого или седьмого нефа, открытые вовнутрь ряды капелл, не изменили своего основного плана. Но устройство хора с обходом, теперь нередко удвоенным, в котором продолжаются боковые нефы, и венцом капелл, тесно придвинутых одна к другой, производит совершенно иное впечатление, чем устройство романского хора. Абсида отсутствует в готике, равно как и крипта под алтарем. В развитом готическом плане хор имеет многоугольный план и представляется как бы половиной центральной постройки; в таком виде, приподнятый на несколько ступенек над полом трансепта, он только теперь срастается с продольным корпусом и трансептом в одно вполне органическое целое. Помещением для священнослужителей служит лишь внутренняя, соответствующая среднему нефу часть хора, отделенная от обхода посредством загородок, а на западной стороне отгороженная от остальной части церкви, предназначенной для мирян, богато расчлененным и разукрашенным леттнером, или лекторием. Украшение окон витражами начинается с хора, но часто распространяется и на продольный и поперечный корпуса. Все окна предназначались для цветных стекол; именно им готические соборы обязаны своим теплым колоритом, смягчающим иногда несколько рассудочную сухость строго рассчитанной архитектуры и сообщающим внутреннему пространству мистическую таинственность; кроме того, эти огромные цветные витражи, будучи составлены из пропускающих свет, но не прозрачных кусочков, до некоторой степени заменяют собой отсутствующие в готической архитектуре сплошные стенные поверхности.

Fig. 244. Interior of Reims Cathedral. From a photo of Nerdeinov

In the high Gothic churches, the northern, southern and eastern sides are entirely occupied by a number of buttresses and supporting arches, which, for all its restlessness, gives the impression of only dry consistency, although the courage with which here, instead of flesh and blood, is the skeleton, cannot but influence the imagination. But in the western facade, furnished in large cathedrals with two huge towers, a medium portal, over which an enormous “rose” often flaunts, and single or double side doors, the vertical, ascending upward lines are balanced by horizontal lines of galleries and cornices, so that organic dismemberment and inner liveliness. Both main towers, to which even now smaller towers are joined, only in extremely rare cases have they been completed as designed, as a result of which the western facades of high Gothic churches rarely produce a completely harmonious impression. But every time we enter one of these cathedrals, immersed in the mysterious color twilight, we stop in ecstatic surprise before the greatness of the plan and the extraordinary art of the builders, who so easily joined these stone ribs, and admiringly admiring a mass of tender and elegant details. Even the East did not create structures that, in their fabulous splendor of the interior, would be equal to skillful Gothic buildings. Among the buildings of world architecture there are monuments more or less interestingly executed, but never anywhere has it created anything more sublime than Gothic cathedrals.

At the head of the churches of the French high Gothic should be put Chartres Cathedral. From its building, burned down in 1194, only the western facade survived (see fig. 170). With extraordinary enthusiasm, the clergy and citizens began to restore the cathedral. By the time St. Louis came to the throne (1226), the choir and longitudinal corps were ready, but the whole building was consecrated only in 1260. Here, for the first time with a three-nave longitudinal body and a three-nave from north to south, the transept choir, very extensive, consists of five nave Each round pillar is decorated with just four service pillars; the windows are only two-bladed, with faint hints of patterned bindings, but already occupy the entire width of the longitudinal (wall) arches; three supporting arches, one above the other, of a very characteristic shape, are already propping up this magnificent structure. The main advantage of Chartres Cathedral is a full row of stained glass windows. At least in this respect, this church, the ancestor of the high Gothic, has fully retained the impression that the interior of the Gothic church made to our time.

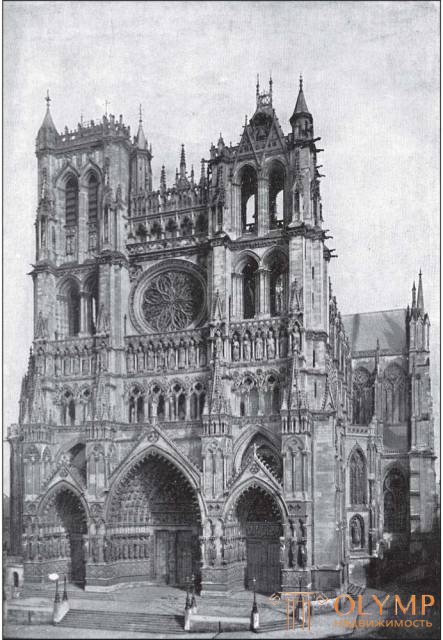

Hons counted among the wonders of the Gothic style the Parisian (see fig. 170), Chartres, Reims and Amiens cathedrals. Reims Cathedral, restored after a fire in 1210, was in 1241 already so rebuilt that it could go to the cathedral chapter. But its magnificent, unusually luxurious facade was completed by the project of the second half of the 13th century only at the end of the 14th century. The longitudinal hull of this temple is a three-nave; The five-faceted device begins only with a transept, which turns into a choir. A simple (not double) choral circuit, representing half a decagon in plan, forms a striking contrast with the five chapels surrounding it in the form of a crown. The middle nave is more than twice as high as the lateral ones (fig. 244). Massive pillars here are equipped with only four senior service columns. Younger columns in both Chartres and Amiens cathedrals begin only above capitals, which are richly decorated with realistic leaf motifs. In the choir chapters built already in 1215, window covers for the first time received a real patterned finish, albeit a very unpretentious type. Inside this cathedral, strength and grace are combined with strict grandeur. Appearance is, as far as generally allowed by the Gothic, in surprising agreement with the noble proportionality of the internal parts. Even the system of buttresses and supporting arches makes a calm impression by the nobility and strictly commensurate with the power of its forms, and the three-story, most magnificently decorated with sculptures, the western facade belongs to the top of the Gothic. The tall pointed timpans of its three portals were turned into windows with patterned crooks, so the pedimental sculptural groups had to be moved to the triangular fields of high imperial levels. The third floor, above which a pair of unfinished towers rise, partly damaged in the XV century from a fire and left without spiers, consists of a series of canopies established by statues, with imperial strings and phials. In this facade, a clear calculation, warm feeling and love for pomp entered into an unbreakable union with each other.

Fig. 245. Amiens Cathedral. From a photo of Nerdeinov

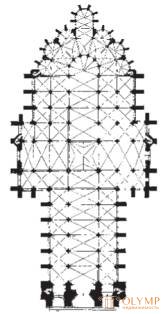

Fig. 246. Plan of the Amiens Cathedral. By Degio

The new building of Amiens Cathedral (fig. 245) was started after the fire of 1218. The oldest parts of the western facade, executed before 1240, are older than the facade of Reims Cathedral, but it was completed only in the XV – XVI centuries. Amiens Cathedral, called the Gothic Parthenon, surpasses its older Reims brother in the consistency and majesty of architecture, but is inferior to it in the purity and charm of individual forms. The ancient parts of the facade, from the towers of which only fragments remained, make a low impression with low imperils of their portals and stretching one above the other horizontal galleries. In Reims Cathedral, the longitudinal corpus is longer than the choir, and in Amiens the choir has grown so much that the distance between the center of the cross and the western main portal is equal to the distance from the center of the cross to the eastern end of the choir, which is formed by a very prominent, as in the Norman-English churches, the middle chapel in the name Blessed Virgin (fig. 246). And here the longitudinal corpus is three-nave, and the chorus, adjacent to the seminiferous transept, has five naves; in accordance with the heptagonal ending of the choir, its simple roundabout is provided with a crown of seven chapels, which, of course, are less extensive than the five chapels of Reims Cathedral, appear therefore higher than in reality. The partition of window covers is more complicated. Here, for the first time, windows are divided into parts by four vertical slabs; the arches of triforia — six; richer is also the patterned cutting of bindings in the lamellar part of the windows. Be that as it may, the Amiens Cathedral is one of the most noble architectural monuments in the world. His influence spread far from France.

To surpass the height and grandeur of the Amiens Cathedral aspired to the Cathedral in Beauvais. His extremely brave choir, the plan of which was copied from the Amiens Choir, was built from 1225 to 1272; but at the end of the 13th century, it collapsed and then was rebuilt with a double number of arcades, the spans of which became relatively narrow. One of the consequences of its extraordinary height, but not harming the general impression, is that the chapels are below the bypass, in the walls of which windows could therefore be made above them. The Gothic choir of the old cathedral at Le Mans (1117–1254) is also of enormous size, with its heavily dissected complex pillars, which, like the pillars of the Bourges Cathedral, reduced the thickness of the service columns, but increased their number. Magnificent windows and a good proportion of this choir make it one of the most beautiful and spectacular rooms in high Gothic. The magnificent view of the reign of Saint Louis was given to the church of Saint-Denis Abbey (rebuilt in 1231), from the original, early Gothic building of which only the western porch and the lower part of the choir survived. In the new building of this church, the gallery of triforia, due to the fact that their rear walls were pierced and glass was inserted into the holes formed, first merged with the windows; Thus the last logical conclusion was made from the gothic system, which later found its use in many localities. At that time, the Notre-Dame de Paris, whose transept received (since 1257) its magnificent facades - works by Jean from Chel, was subjected to perestroika. But the most beautiful Parisian building is the famous Saint-Chapelle (Sainte Chapelle) at the royal palace on the Isle of Cite, built by Pierre of Montreuil (1243–1248). Like most of the castle chapels, it consists of two floors. The low, crypt-like lower chapel has three naves. A single-nave upper chapel with large, full-length, stained-glass windows seems to be a construction of rubies and sapphires inserted into an elegant stone setting. All details, including sculptural ones, are amazingly delicately executed, and all the decoration of the chapel is brought into complete harmony with the nobility of architectural forms.

The chapels in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the archbishop's palace in Reims and the abbey of Saint-Germain, near Beauvais, have similar chapels.

Among the exemplary churches of high Gothic style, built in the middle of the XIII century in le-de-France, Picardy and Champagne, are also the cathedrals of Troyes, Chalons, Meaux, Saint-Quentin and Tula. On the right bank of the Loire, the architecture of the Tours Cathedral, whose façade is already Gothic, follows in the footsteps of this French school; as an elegant structure of high Gothic, you can also point to the church of St. Juliana on Tour. Generally, to the north of the Loire, the victory at that time was easy to reach for the new architectural style, no better than the ideas and aspirations of the epoch.

A slightly different look than in the middle and southern parts of Northern France, received a high Gothic style in Normandy, which, as we already know, early developed independent forms, transitional to Gothic, and in this era was influenced by both France and England. Although the Gothic architecture of Normandy adopted heavily dissected complex pillars, it still retained many early Gothic features: windows that rarely occupy the entire wall do not have patterned crooks; as the remnants of the empor stretched under the windows of the gallery, the device which is facilitated by the empty spaces between the double walls; the natural leafy ornament of capitals is sacrificed to the early Gothic motifs of stylized buds; towers are kept above the medium cross, the height often surpassing the slender twin towers of the facades; the middle choir of the choir in the name of the Virgin, on the model of the English churches, stands out strongly from the crown of the choir; The eastern sides of the transept's wings are also often provided with chapel niches. The majestic Norman churches of this kind with their spiers of their towers high above cities. From the old buildings, the three-nave Rouen Cathedral, which has a richly dissected eastern end of the choir, the noble three-nave cathedral in Lizier, whose choral detour is decorated with double pillars, and the Bayeux cathedral, with its elemental half-decade choir, were rebuilt. The most famous Norman temples, built in the flourishing period of the high Gothic, are the three-nave cathedral in Sé, with its unequal spiers of the western towers, and the five-foot cathedral in Coutances, with internal pillars, a double choral bypass and a huge tower above the center cross, the most beautiful and best preserved tower in Normandy.

The fact that the XIII century. began in northern France in the field of Gothic architecture, imparting warm feeling and a lot of wit to his creations, continued coldly and rationally in the 14th century. The style of this century, which, for all the voidness of its individual forms, still quite often succeeds in combining purity and grace with simplicity and grandeur, Degio gave the name "late Gothic doctrinal". During this time, few churches were built or restored in the heart of France. Under the onslaught of political storms (the Hundred Years War), an outbreak of artistic life was followed by its lull; but nevertheless the construction activity did not cease: the church of the abbey of Saint-Denis, the Parisian, Lansky and Amiens cathedrals received new additions and extensions. In Normandy, the cathedrals of Rouen and Xie continued to be built. Church of sv. Petra in Cana is endowed with the most beautiful tower of the time (1308), if not all times; in the 14th century, the magnificent church of St. Ouen (S. Ouen) was built in Rouen. The three-nave in the longitudinal case and the five-nave due to the side chapels in the choir, the church is not a very successful attempt to finish the chorus with half of the octagon in such a way that of its five chapels both extremes have twice the width than the rest. Complex pillars here are consistently developed, high triphoria brought to the windows, late Gothic torches appear in the through-carving of bindings, constructive parts of strict proportions, gaps inside the building of unmatched clarity and charm. A similar “doctrinal” completeness is the Cathedral in Troyes. Church of sv. Urbana in Troy varies the constructive ideas of the Gothic style more intricately: with double walls, windows are arranged either in the outer or in the inner wall, and therefore they have both outer and inner bindings. In the late Gothic style of this direction, too much premeditation hurts the power of the impression.

Gothic style, which developed in church buildings, soon caused a complete revolution in forms and secular architecture. However, it was not so much the constructive elements as ornamental forms that underwent a change. The championship in the construction of castles belongs to France, but in the architecture of the town hall, these creatures of the free spirit of the townspeople, it lagged behind Germany, the Netherlands and Italy. Of the palaces, castles, hospitals and monasteries of luxurious architecture, hundreds of which grew on French soil during this time, relatively few survived; but still it is in the north of France that a number of exemplary buildings of this genus are located. Of the episcopal palaces, the Lansky, built in the 13th century, is the best preserved. The heyday of the castle architecture dates back to the end of the 13th century - by the time the Duke John of Berry was competing with his royal brother Charles V in the love of luxury and in the patronage of the arts.

Fig. 247. Statue of a violinist in the House of Musicians in Reims. With photos of Girodon

Ramon de Temple and his disciples Jean-Saint-Romain and Guy de Dahmartin are mentioned as court architects of Charles V. The multi-tower medieval castle of the Louvre in Paris, the construction of which lasted for all the Gothic centuries, is known to us only by descriptions and drawings. Without a doubt, it was the most magnificent and luxurious royal palace in Western Europe. His large spiral staircase openwork work was considered the best work of Ramon de Tample. In Northern France, Gothic dwelling houses have been preserved in Reims, Provins, Lana, Angers, Beauvais, Amiens, and others. For example, the so-called House of Musicians in Reims is remarkable, its walls, with four Gothic windows of very elegant form, are decorated with sedentary figures of musicians placed in five beautifully framed arched niches (Fig. 247). From the town halls of Northern France of the 14th century a simple and massive building in Clermont de l'Uze belongs. But many other buildings surpasses the fortified monastery of Mont Saint Michel, majestically towering on the rocky island of the Channel. His church is partly dogotic, partly Late Gothic. The monastery building la Merveille seems almost a work of nature. Both lower floors, belonging to the end of the XII century, have an early Gothic character; the upper floor is built in the style of transition to the high Gothic style of the XIII century. On the middle floor there is a magnificent knightly hall supported by columns and a two-refectory refectory, illuminated by 23 deep, close-to-close windows; in the arches of these windows, we unexpectedly encounter oriental stalactite cells (see t. 1, fig. 641), the Danai gift of the crusades. In light and noble forms, the cloister gallery and the dormitory of the upper are built.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)