The new period, which we will call, in contrast to Christian antiquity, the early Middle Ages, gradually replaced the old one. It was conditioned and limited - after the victory of Islam finally suppressed the Hellenism of the Persian and Egyptian cultural centers, plunged into the “embrace of the East” already in the ancient Christian era — in Byzantium with the power and pomp of the Macedonian dynasty, and in Western Europe - with the brilliant supremacy of Carolingian and отт shtransplayers. empire. Both there and here, secular and spiritual rulers consciously sought to maintain contact with classical antiquity, weakened by the direction adopted by the Christian art of Hellenized, but now again becoming distinctive West Asian East. The fact that all this movement from the East (in our opinion, correctly characterized by Strigovsky in essential terms) was limited to architecture and ornamentation, while sculpture and painting, regressing and turning aside, nevertheless did not leave, at least in some Forms, the old Hellenistic basis, will be clear by itself, if we take into account the decorative nature of the late oriental art. This process of transformation of architecture and ornamentation in the oriental spirit, accomplished under the influence of the continental countries of Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt, was already completed in Byzantium (preserving, as far as possible, the Hellenistic basis), while in the West, which perceived the eastern currents through Constantinople, partly through Ravenna and Milan, partly in what we agree with Strigovsky, through the ancient colony of the Ionians, Marseille, - new forms were still being formed. Studying their development, we do not consider it possible to completely lose sight of the Hellenistic tradition that went through Rome. In general, the evolution of artistic styles, often extremely confusing, we cannot look as simply and one-sidedly as some other researchers. It is in the field of Carolingian and Ottoman art that Roman-Hellenistic traditions are clearly revealed, and it was on the soil of Rome that the early Christian Eastern tradition, which was carried by monasteries, merged with special, northern elements into the so-called Romanesque architectural style, the beginnings of which are noticeable at the end this era. Nevertheless, we must begin our acquaintance with the art of the early Middle Ages from the East.

Having lost the southern and eastern provinces, rejected by the Arabs, the Byzantine Empire in its new borders became only stronger and more united. Constantinople was undoubtedly the most powerful, richest and magnificent European city of that time. His ships plowed all the seas; his ornate costumes determined the fashion of all cities; his silk and gold products flooded all countries, but unsuitable art declined here. The ridicule of the victorious confessors of Allah over the veneration of icons, which took on the character of true idolatry, found a response on the shores of the Bosporus. The emperors set themselves the task of returning the people to the cult of the early Christianity, who did not know the icons. Leo III Isavr, in order to prevent the most gross manifestations of the veneration of icons, in 726 ordered to hang up the church image higher, and in 728 completely forbade worshiping them; In 754, Constantine V ordered that church mosaics and frescoes be painted over with lime, and although Empress Irene restored the veneration of icons in 788, most of the emperors of the first half of the 9th century restored. were the same iconoclasts as its predecessor Leo IV. Only with the death of Emperor Theophilus (829–842) did iconoclasm cease when the sovereign's widow, Empress Theodore, returned their former shrines to the churches. Iconoclasm led all the visual arts in an equally deplorable state. Even the architecture for two centuries (659-850) remained constrained. Only the powerful, patronized art of the Macedonian dynasty (867–1056) broke these chains. With her, all the arts rose up to a new life. The medieval Byzantine art of the first blooming pore exceeded the art of all other European countries with an understanding of forms, a wealth of colors and technical knowledge.

Already the founder of the Macedonian dynasty, Vasily I (867–886), building and renovating buildings, promoted the development of extensive activities in all branches of architecture. Under him and under his successors, the Great Imperial Palace in Constantinople, thanks to the new round halls and domes, was getting more and more oriental; At the same time, in the church architecture, the old basilic style, having passed completely to the West, gave up its place in Greece to the central and semi-basilic systems of temple-building.

Fig. 59. Ionian capital with skewed sides of the Macedonian era of Constantinople. According to Strigovsky

Constructions of this kind remained extremely small in Constantinople. From the palaces of Constantinople there was only a magnificent three-story ruin with slender semicircular arches, known as Tekfur-seray. Its outer walls are lined with red brick and slabs of yellowish-white marble, forming beautiful patterns. We will not return to the underground reservoirs, the columns of which in this epoch are usually crowned with the so-called Ionic impostor capital (Fig. 59), in which the Ionic, volute-supplied cushion is pinned down by the impost.

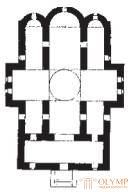

Fig. 60. The plan of the monastery church in Skrypa, in Boeotia. According to Strigovsky

By the beginning of the XI century is the most magnificent of all the Byzantine churches of Greece - the main church of the famous monastery of St.. Luke at Stiris, at Phocis, is a building to which Schultz and Barnsley dedicated a special work; Half a century later, a monastery church was built in Daphne near Athens. Both of these churches are crowned with huge, three apse wide, domes resting on eight pillars connected by a system of buttresses into one massive and solid whole.

We find a similar construction in the church of Sts. Nicodemus in Athens (1045), the main dome of which is surrounded by 12 small domes. The transitional place between the old and the new systems is occupied by the curious Nea Moni church on the island of Chios, built between 1042 and 1056. The system of octagonal supports characterizing the interior of the churches of the monastery of St.. The bows and monastery of Daphne, is absent here, or, more precisely, expressed by means of eight pairs of double columns leaning against the main walls, placed on each other. The dome lies directly on the quadrangle of the circumferential wall, the entire width of which on the east side is occupied by three apse niches.

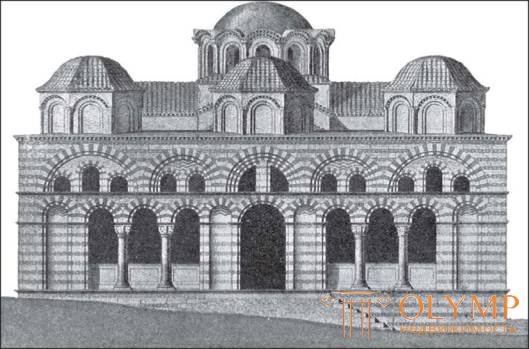

A more elegant style is presented in Constantinople by the Church of Our Lady, Agia Theotokos (Fig. 61), built, in the opinion of Choisy, Bayeux and others, in the 9th century. Here the drum of the middle dome is supported by four round columns connected by arches; at the base of it are four “sails”; three lower domes rise above the narthex; the apse opens outwards with an arcade, the domes of the domes are decorated with arcades outside; wall cladding - two-tone. In the small old cathedral church of Panagia Gorgopico in Athens, many features of the new style are already being displayed. Of the other Athenian churches, the beautifully dismembered Church of Kapnikaraya and the Church of Theotokos (Our Lady) fully express it, but the small church of the same name in the monastery of St. Bows in Phocis, the high domed drum of which is particularly graceful towering on sails supported by columns.

Fig. 61. The west side of the Church of Our Lady of Constantinople. According to Salzenberg

In the Macedonian period, monasteries began to be founded on the far from Mount Athos, which occupies one of the plaits of the Chalcis Peninsula. The main buildings of the 20 Athos monasteries, in which Byzantine art still exists today, are usually surrounded, according to the testimony of Heinrich Brockhaus, by a quadrangular courtyard; its middle, in contrast to the western monasteries, is occupied by a detached domed church, a special type of which was established, however, a little later.

2. Painting (between 717–1057)

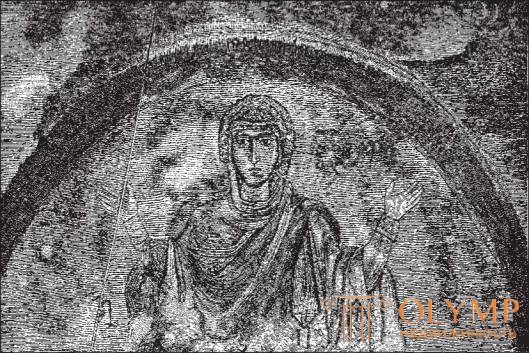

Fig. 63. Praying Mother of God. Mosaic in the church Koimesis in Nicaea. According to wulf

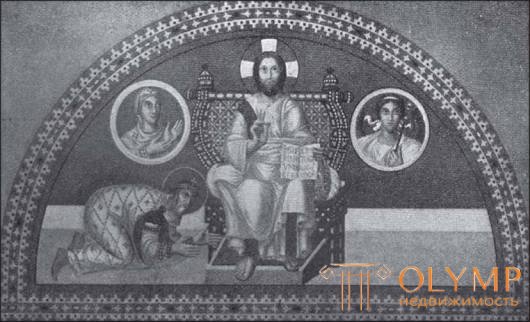

Fig. 62. The emperor worships Christ seated on the throne. Mosaic in the narthex of the temple of St. Sofia in Constantinople. According to Salzenberg

Fig. 64. Хвастуны. Миниатюра из хлудовской Псалтыри Никольского монастыря под Москвой. По Тикканену

В средневековом византийском иллюстрировании псалтырей, составляющем одну из главных отраслей миниатюрной живописи, различают два направления, исследованием которых, после Шпрингера и Кондакова, занимался Тикканен. Церковное, или монашески-богословское, как его называли, направление является вместе с тем и народно-символическим. Многочисленные иллюстрации, имеющие целью поучение и наставление в духе христианской Церкви, сопровождают текст в виде легко набросанных на полях и раскрашенных рисунков, состоящих из небольшого числа фигур на фоне пергамента. Всегда фантастичные, они обнаруживают нередко, при передаче метафорических образов псалмов, своего рода чувство действительности: лицемеру крылатый ангел вырывает огромными клещами язык; злой действительно падает в вырытую им яму; безбожники, «возметаемые, как мякина ветром», падают на струю воздуха, выдуваемого юношей из рога. Что приходит в голову художнику при каждом стихе, то он и рисует. Главный памятник этого направления — хлудовская Псалтырь, принадлежащая Никольскому монастырю, близ Москвы, и написанная, по всей вероятности, в конце XI столетия. В ее миниатюрах фигуры еще коротки и приземисты; лица по большей части лишены экспрессии, но жесты фигур выразительны и жизненны. Среди красок, местами слегка шрафированных золотом, преобладают васильково-голубая, желтая охра, бледно-розовая, тускло-зеленая, коричневая и пурпурная. Насколько причудливо изображены, например, хвастуны (псалом 72, 9; «Поднимают к небесам уста свои, и язык их расхаживает по земле»; рис. 64), настолько же проста и вместе с тем торжественна композиция, представляющая между восходящим и заходящим солнцем пророка Аввакума, который указывает на изображенного над ним Спасителя как на единое и незаходящее солнце (рис. 65).

Fig. 65. Prophet Habakkuk. Miniature of Khlud's Psalms of the Nikolsky Monastery near Moscow. By tikkanen

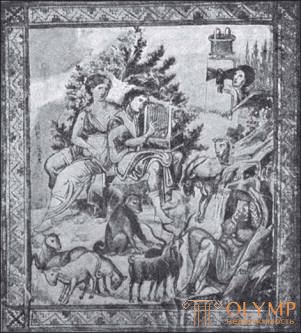

In the 10th century, another secular and courtly direction began to compete with this ecclesiastical, or folk-symbolic, direction of psalter painting, which cares not so much about observing the close connection between illustrations and text, as about decorating a book with large artistic compositions. The most important of these monuments is the famous codex of the Paris National Library No. 139, perhaps the most beautiful among all the illustrated manuscripts. Of its 14 miniatures the size of a sheet, the first 7 glorify King David exclusively, others reproduce various Old Testament events. Their execution is not the same. Some miniatures are imbued with this ancient spirit and their landscapes against the blue sky, the nobility of forms and the pictorial technique of the main figures, as well as the inclusion in the composition as side figures of the personifications of nature, vividly resemble those idyllic Pompeian frescoes in which we recognized the Alexandrian influence (see T. 1, Vol. 4, II, 2). This is the first miniature in order (fig. 66), in which David is depicted as a young shepherd playing the lyre, between a woman personifying Melody and a mountain deity, Bethlehem; David is listening to the forest nymph. The avatars, as in the Osksey's Esquilinian landscapes (see v. 1, fig. 486), are explained with inscriptions. These are also the miniatures “David before Nathan,” “Crossing the Black Sea,” and “Moses receiving the tables of the Covenant.” Other paintings, with a partial or solid gold background, with black outlines and motionless, solemn figures, despite the ancient motifs found in them, have a purely Byzantine style; for example, the Apotheosis of David, in which we see him in Byzantine imperial attire, among the avatars of Wisdom and Divination, and a beautiful picture depicting the praying prophet Isaiah between the figures of the Night and the Dawn on a golden background. Among the Psalters, which in the next century differ in the same direction as the Paris Psalter, not adjoining, however, as close as its best sheets, to ancient art, belong, for example, the manuscripts of the Vatican Library in Rome, the Ambrosian Library in Milan and Christian-archaeological collection at the University of Berlin, whereas, for example, in the Psalter Library of St. The stamp in Venice, written for Basil II (976–979), already appears, along with the coarsening of the technique, unnatural proportions of the later period of Byzantine art.

Fig. 66. David playing the lyre. Thumbnail from the manuscript of the Paris National Library. By Tikkanen

No less purely Byzantine character has the above-mentioned menology of the Vatican Library, written between 976 and 1025. Only a part of this manuscript has been preserved with images of saints, whose memory is celebrated from September to February, and with their lives, but this part contains at least 430 miniatures; many of them - which is an exception for this time - are signed by the artists who performed them. Architectural and landscape backgrounds are still a general rule. Frequent bare rocks with cliffs washed with water; but instead of the sky over the landscape stretches a smooth golden background. Calm figures are drawn confidently and clearly, the drawing is correct, but sketchy and too petty. Faces - oval, on thin lips - a pained expression. Eyebrows, barely breaking over the humped nose, form almost one densely drawn line. Calm movements often resemble antiquity in their beauty, but movements are more or less impetuous, leading to gross errors in drawing. So, for example, the peaceful composition of the Nativity of Christ makes quite a pleasant impression; on the contrary, in the scene of the Adoration of the Magi, the figures of the three magi, which hastily march towards the Mother of God quietly seated on the throne, are completely distorted.

In this era, two branches of applied painting, partition enamel on gold and silk patterned fabrics, equally achieved perfection in Byzantium.

The technique of septal enamel (email cloisonne) essentially reduces to the fact that the contour lines of the pattern are indicated by thin gold partitions soldered to the gold plate, and the spaces between them are filled with colored glass alloys. The opinion that septum enamel was invented only at this time and in Byzantium is erroneous: its homeland must be sought, perhaps, in Parthian or Sassanian Persia. In any case, in Constantinople, in the era of the Macedonian dynasty, it achieves such technical excellence, such purity of colorful tones and such subtlety of design that cannot be found equal.

Fig. 67. Apostles Peter and Paul. Byzantine enamels from the collection of A. Zvenigorod. According to Schulz

In the West, a significant number of works of this kind are kept in cathedral sacristy and collections. Especially famous is the front side of the icon (pala d'oro) behind the main altar of the Cathedral of Sts. Mark in Venice. This icon was ordered in 976 in Constantinople by Doge Piero Orceolo I, but only the enamels of the upper row, such as the medallion depicting Michael the Archangel and six enamels with scenes of the Passion of the Lord and the acts of the Apostles, belong to the flowering pore of Byzantine art; other enamels are added later. No less famous is the golden stavrotek (a casket for the storage of a part of the Holy Cross) belonging to the Cathedral of Limburg-on-Lane, partly a hand-written work of the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII the Porphyrogenitus (913–952), but completed only in 976 for Vasily II. The square middle field of the lid is adorned with a majestic and noble image of Christ seated on a throne, already a few sullen appearance; on the sides of Christ, on two side fields, are represented by John the Baptist and the Virgin, accompanied by angels; in each of the other fields - two apostles. The figures, somewhat short, are placed on a smooth golden background, with no signs of soil under their feet; their symmetrical arrangement in a luxurious frame gives stavrotek enamels the character of artistic completeness. Finally, are known thanks to the publications of Iog. Schultz and N. P. Kondakov numerous enamels of the collection of A. Zvenigorodsky. Of particular note are small, designed to be worn on the chest, round medallions with belt images of saints (enkolpii); among them is quite remarkable a series of medallions of the X century, consisting of images of the Savior and the apostles and extremely characteristic of the first era of the heyday of medieval Byzantine art. Here, as in many other works of this kind, the Savior, the apostles Peter and Paul (Fig. 67), even when depicted en face, look not directly, but to the side. And in the painting of enamels the subtlety of work and the freshness of paints are not able to tell the inner life schematically correct drawing.

Unfortunately, we will not speak in detail about silk fabrics, which in the early Middle Ages played the first role in weaving. Round, oval or polygonal fields on fabrics are usually ornamented with stylized leaves and filled with symmetrically arranged figures of four-legged animals and birds. Luxurious matter used in abundance to decorate churches and palaces, carpets and pillows, costumes of secular and spiritual nobility, with their bright colors brightened and revived the form.

3. Sculpture (850–1057)

Fearing reproach in idolatry on the part of their Muslim neighbors, the Byzantine rulers, after the restoration of the veneration of icons, even more strictly than before, began to forbid round plastic images of saints. Only in such purely decorative figures, such as, for example, beautiful angels, later transferred to the Venetian Cathedral of Sts. Mark, one can guess that the statues have not completely disappeared at that time from Byzantine art. The relief was treated less strictly, but the monumental Byzantine relief no longer existed.

In Constantinople, the whole sculpture turned now again to applied art; still carved ivory tablets, joined by gold products, are the main monuments of plastic works of Byzantine masters. Having developed in the same direction with the thumbnails, they discover many points of their contact with these latter.

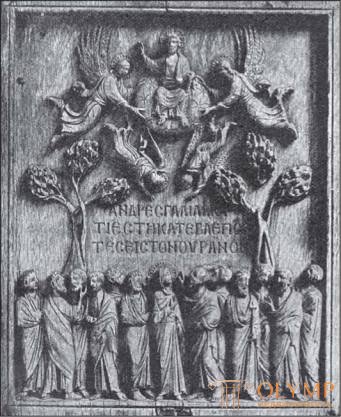

Fig. 68. Ascension of the Lord. Byzantine relief. Ivory carving.

Where the figures are too elongated, and the poses are deliberately motionless and lifeless, we are dealing with works performed in the second half of the XI century.

As before, religious subjects predominate on ivory, but along with them secular, even mythological subjects, copied, as pointed out by Greven, directly from ancient specimens, continue to occur. As the best work of the Macedonian period, an ivory plate with the image of the Mother of God sitting on the throne is shown in the “Annals” of Didron, which used to belong to de Bastard in Paris. Pure contours of the face, noble proportions, calm, majestic posture and expression of gentleness distinguish this relief. By the end of the Macedonian era, we attribute the strictly symmetrical Ascension of the Lord, in the Florence National Museum (Fig. 68). As an interesting example of pagan scenes on ivory of this time, the exquisite reliefs of an ivory box from Veroli, in the Kensington Museum in London, should be mentioned; here we see, for example, Europe on a bull and Achilles at the centaur Chiron. The Ivory box with similar mythological images is also owned by the Florence National Museum. By the time between 1026 and 1034 Carry a small chalice of the monastery Xiropotama on Mount Athos, carved from soap stone (steatite) published by Brockhaus; it is decorated with small reliefs of liturgical content, surprisingly fine work. Of the gold items, the relief plate of the Louvre Museum in Paris deserves attention, which depicts an angel at the Holy Sepulcher and two myrtle bearers in Byzantine forms of the Macedonian time. We will see below how the relatively healthy and vital Byzantine language of the forms of this great bicentenary (approximately from 850 to 1050) already at the beginning of the next epoch becomes fanciful and mannered.

4. Art of Armenia and Georgia (IX – XI centuries)

A beautiful country between the Caucasus Mountains and Ararat, adjacent on the one hand to Asia Minor and Persia, on the other - to Russia, already in the previous era, as we saw, took a lively part in the development of church central architecture. From the 9th century, distinctive national trends are clearly revealed in Armenian art. The plan of the Armenian church buildings of this epoch is characterized by a general oblong shape, with a dome crowning an average space. The cross that these churches form inside is not Greek, because its eastern and western ends are longer than the northern and southern, but not Latin, because the eastern and western ends are of equal length: it is Armenian. The apse niches, round inside, do not stand for the rectangular outline of the plan. The facades are dissected by triangular niches and false arches embedded in the walls. The dome lies on the drum, polygonal on the outside, and inside it is often round, cut by semicircular-arched windows; his own roundness is masked outside by a pyramidal or conical roof. Geometrically simple forms inform the Armenian churches, both outside and inside, the charm of artistic completeness.

Already the church of sv. Hripsime in Vagharshapat (Echmiadzin), which arose hardly earlier than 800, although it was considered to be two centuries older, shows this system in its most consistent development. The plan of this church is very interesting (Fig. 69). All four sides have semicircular niches, indicated from the outside by triangular hollows hitting the thick walls. Inside they correspond to strongly protruding pilasters forming a system of supports supporting the dome. The church in Pitsunda (in Abkhazia), built in the 10th century, was previously also attributable, at the latest, to the 8th century. The long western part of this temple makes it very much like a domed basilica. Over its four main pillars, horseshoe arches are lined. In later churches, a peculiar Armenian national pattern appears, connected, however, somewhat artificially with individual architectural elements. Antique plant motifs are rare, garlands of curls are completely absent, the leaves for the most part follow one by one; The main role is played by braid and ribbon ornament. Capitals and bases of rare columns and more frequent semi-columns consist of rounded pillows. Finally, in places on “sails” and columns, purely Arabic motifs of stalactites come across (see t. 1, fig. 643). Especially rich in the ruins of churches of this time, among which are frequent and octagonal in the plan, the city of Ani, the so-called Armenian Pompey. The dilapidated tuff-built Patriarchal Church of Ani (Fig. 70), completed in 1010, represented a typical example of the Armenian Church, which has a rectangle in plan; however, its dome rested no longer on a system of supports connected to the walls, but on four freely standing, heavily dissected pillars, as in the more ancient Armenian churches (see above). Pulled in

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)