Architecture

Rome, which was no longer the "head of the world", became, at least since the return of the popes from Avignon, again the head of Christianity; and fortunately, most popes of the XV century. enthusiastically joined the humanist movement. We meet painters of a new direction in Rome already at Martin V (1417–1431), sculptors of a new direction - at Evgeny VI (1431–1447). But the first patron of art on the throne of St.. Peter was Nicholas V (1447-1455); his love of art was found mainly in the field of architecture. If Roman documents do not mention Alberti’s construction activities in Rome, this does not force us to distrust Vasari’s news, according to which the famous Florentine was the soul of Nicholas V.’s construction enterprises. Alberti, an eminent scientist, perhaps did not deliberately speak as an architect, but his friend Bernardo Rossellino was the author of Pope’s extensive construction plans, which, unfortunately, remained unfulfilled. Also the names of the famous Tuscan masters, Giovannino de Dolci (died in 1486) and Giacomo da Pietrasanta (died about 1495), are found in the construction estimates of Nicholas V. The typical Pope-humanist Pius II (1458-1464) to such an extent he gave his money and love to buildings in Siena and in his hometown Pienza, that in Rome itself its construction activity was limited only to the expansion of the Vatican palace. Under Paul II (1464–1471), who, like Cardinal Barbo, began until 1455 the construction of the church of San Marco and the new building of the Palazzo di San Marco (now the Palazzo Venezia) in Rome, the Tuscans Giacomo da Pietrasanta, Giovannino de Dolci, Meo Del Caprino of Settignano (1430-1501) and Giuliano da Sangallo advanced not only the construction of these groups of buildings and the Vatican, but also the restoration of many old buildings in Rome. The present golden age of early Renaissance architecture in Rome was the time of Sixt IV (1471–1484), the most devoted to art from the popes of the fifteenth century; as it was in his pontificate, as Milanese, Müntz and Rocky showed, the above-mentioned masters developed the swift activity described in the writings of Letarulli and Shtrak, which Vasari mistakenly attributed almost exclusively to the account of one Baccio Pontelli, actually engaged in Rome (since 1482) only fortification works.

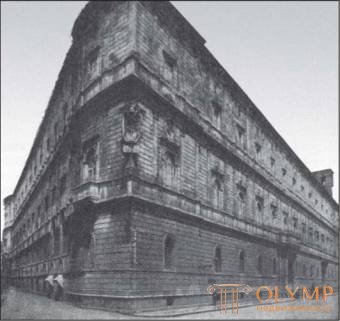

The Palazzo Venezia, designed, probably, by Giacomo da Pietrasanta, with its teeth over strongly protruding, laid out on the consoles cornice and rectilinear windows in both upper floors, gives the impression of Gothic construction; but its internal gallery, connected by arcades with poles reinforced in the lower floor by Tuscan-Doric, and in the upper floor by Corinthian half-columns, adjoins closer to the prototype of the Colosseum (see t. 1, fig. 501, a) than any other earlier construction The arcades of the Palazzo Venice should be made in the cleanest classical forms of the early Renaissance facade of the church of San Marco. Giacomo da Pietrasanta, by this creative force of the Roman early Renaissance, built the church of Sant'Agostino (1479–1483), whose curved, volute-filled, half-gables of which reproduce the same half-gables of Alberti. Giovannino de Dolchi built the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, famous for its paintings. Meo del Caprino, who built in the years 1492-1498. Turin Cathedral, was then, as you can think, the builder of the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, perhaps also the author of the facade of the church of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. Under Innocent VIII (1484–1492), a clean, free and strictly following Roman antiquity architectural style was established. The first and best creation of it in Rome was the Palazzo Cancelleria (1486–1496), formerly considered to be the debut of Bramante in the field of the High Renaissance. But since Bramante moved to Rome only after 1499, this elegant building, after the arguments cited especially by Njoli, Bernich and Fabritsi, is almost no longer recognized as a work by the great Urbinian. In any case, Palazzo Kancelleria with its thin profiles and still weak protrusions is closer to the early than to the High Renaissance. Its facade (fig. 466) has in its basis the facade of Palazzo Rucellai in Florence created by Alberti. The lower floor, which has not yet been divided by pilasters, has no other partitioning, except for the projecting parts of the common facade (the so-called risalite), portals and simple windows with semicircular arches. But in both upper floors, each pier between the charmingly framed windows is adorned with pairs of flat pilasters in the Corinthian style, above which the entablature stretches. Cornice cornice with teeth is issued, like all pilasters, is relatively small. In the magnificent courtyard, the first and second floors are turned into arcades, the lower columns of which belong to the Tuscan-Doric order, the upper ones - freely processed Ionic, only without volutes, while the third floor is decorated with Corinthian pilasters of the noblest form.

Fig. 466. Palazzo Cancelleria in Rome. From the photo of Anderson

All profiles are outlined with the greatest taste. The combination of large and clear main proportions with moderate and noble individual forms, both on the facade and in the courtyard, is surprisingly harmonious.

On the question of who, if not Bramante, was the creator of Clackhelleria, various answers were given. Assuming that this building was really begun as early as 1450–1455, it would not seem incredible to assume that the project belonged to none other than Alberti. If we add to this that Laurana, the builder of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, was influenced by Alberti, then the continuity of development from Alberti to Bramante is even clearer than before, and we do not need to deny that Bramante, as Vasari said, upon arrival at Rome was finishing the construction of the Cancelleria. The whole of the Roman early Renaissance, in this way, to which the palaces close in style adjoin, such as the noble Palazzo Giraud, now Torlonia, and Palaceto di Bramante, appear Tuscan in character. Nevertheless, thanks to these buildings, Rome became the cradle of the High Renaissance.

In the Kingdom of Neapolitan during the reign of the Angevin dynasty reigned gothic. The elegant Gothic portal of 1415 has the chapel of San Giovanni de Pappacoda. The attempt to plant a Renaissance in Naples, undertaken after 1427 by Donatello and Michelozzo with their monument to Cardinal Brancacci, remained single. Only in 1443, with the transition of the Neapolitan throne to King Aigonese Alphonse the Magnanimous, who, being an enthusiastic admirer of classical antiquity, surrounded himself with a whole headquarters of humanists, penetrated the spirit of the Renaissance in Naples. However, a certain time passed before it was revealed in Neapolitan architecture. Almost nothing has been preserved here from the buildings of Giuliano da Sanghello, but the Kapuan Gate, built by Giuliano da Mayano, and some of the new buildings of the Alfons Castel Nuovo residence remained. Pietro da Milano from Varese (died in 1473), the architect who owns some parts of the Renaissance Castel Nuovo, appears in Naples only in 1455, after he, a true representative of the Como school, tried his mostly decorative art in various cities of Italy. In 1455–1457, as Berto proved, he simultaneously directed Castel Nuovo to build a new hall for festivities and Alfons’s famous two-story marble triumphal arch, which, although inorganically wedged between two harsh towers, is Castel Nuovo, yet by the authenticity of its ancient Roman details was in Neapolitan architecture a new phenomenon. However, the assumption that Pietro da Milano composed the first sketch of this magnificent structure is just as little proven as the conjecture that he belongs to Leon Battista (Bernich) or Francesco Laurana (Rolfs). It was rebuilt, as Fabritsi proved, undoubtedly Pietro (1461–1470).

“The richest and most complete monument of decorative art in Naples and at the same time one of the most magnificent buildings in all of Italy” (Burkgardt), the crypt of the Neapolitan Cathedral, was made by Tomaso Malvito, also a native of Como. Most of the monastic courtyards, portals and chapels of the Neapolitan churches of the XV century are made in the Florentine style. Neapolitan palaces of this time, such as, for example, the Palazzo Cuomo (1464–1488; now the Museo Filandjeri), also adjoin the style of the Florentine buildings lined with rustics. Even the South Italian masters of transition from the 15th to the 16th centuries, such as Giovanni Donadio from Calabria (died in 1522), the builder of Santa Maria della Stella (1519), a simple early Renaissance church, were still under Florentine influence. .

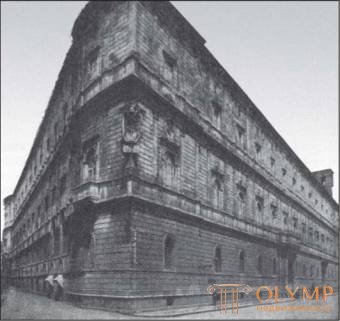

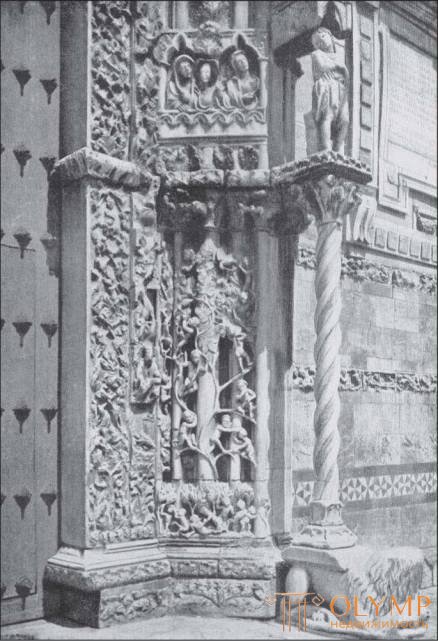

During the entire XV century. the architecture of Sicily remained true to the Gothic style. Renaissance motifs interspersed with Gothic for the first time appear in the charming portal of the Church of Santa Maria della Catena in Palermo (Fig. 467). Separate architectural parts were performed here since the middle of the 15th century in the Renaissance style, and especially their sculptural decoration, by the hands of Upper Italian and Tuscan craftsmen. We also know that Pietro da Milano, having interrupted work on the triumphal arch of Alphonse I in Naples, lived for some time in Palermo, and the sculptors Hajini from Bissone on Lugansk Lake, who were written by Beltrami and Carvetto, moved in 1465 from Genoa where in 1448 they decorated with excellent reliefs the chapel of St. John the Baptist in the cathedral of Palermo, so that here (for example, at the cathedral bowl for holy water) show his art in ornament in full splendor. The earliest works of the Tuscan and Upper Italian Renaissance also remind of the framing of the portal of the Messina Cathedral, with its frolicking vines, which were not entirely freely modeled by naked boys (Fig. 468), which appeared, perhaps even before 1400. At the end of the century, the new style conquered the entire peninsula.

Fig. 467. Portal of the Church of Santa Maria della Catena in Palermo. With photos Alinari

Plastics

On the banks of the Tiber in the XV century. there were not enough local workers to cultivate the fields of the visual arts, but not the customers, who wore mostly tiara or cardinal caps, who did not miss the chance to transfer foreign artists to the Roman soil and collect interesting works.

Fig. 468. Sculptural decoration of the portal of the cathedral in Messina. With photos Alinari

During the first five years of the 15th century, the heirs of the ancient family of Kosmati worked in Rome. The monument to Cardinal Stefaneschi in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, performed by master Pavel after 1417, is still so monumental in the old spirit, so noble in its simple architecture, the figure of the deceased is still so strict in its dignity that it can be counted among the most beautiful artistic the works of Rome. But this relic of the Roman antiquity in Rome has nothing to do with the Renaissance, which came from the north. The marble tabernacle of Donatello, the papal tombs of Pollaiolo in the cathedral of st. Peter were only purely Florentine works on Roman soil; the same can be said about the main sculpture of Antonio Filaret - the bronze doors of the cathedral of st. Peter in Rome (1439–1445). Anyway, it is here that we get to know Filarete as a sculptor. These doors do not even reach the artistic height of the eastern doors of the Florentine baptistery. Nevertheless, their relief images from the history of the papacy are captivating with their content, pagan mythological scenes reviving lush arabesque frames lively and boldly arranged. A small equestrian statuette of Philaret (1465), in Dresden Albertinum, is good, but she, like the remains of a monument to Portuguese cardinal Antonio Chiave (died 1447) in the church of San Giovanni in Lateran, shows that Philarete really has outgrown the old style but not yet fully mastered the new. Only Mino da Fiesole, who lived in Rome in 1471–85, entered into such close relations with the Roman sculptors that he began to be considered a member of their guild.

The Romans themselves were very poorly represented in this sculptors guild: Paolo Tacconi, nicknamed Romano (c. 1415–1470), Gian Cristoforo Romano (1465–1512) - one of the main craftsmen who worked on the plastic decoration of Chertozy in Pavia. About the other masters of this guild, we know that Isaiah da Pisa was a Tuscan, Giovanni Dalmatia was from Trau in Dalmatia, Andrea Breño (1421–1506) from Osteno (near Como) was a Lombard. Almost all of them worked together with Mino da Fiesole. Isaiah da Pisa and Paolo Romano performed together in 1463 for the Cathedral of Sts. Peter canopy of sv. Andrew, the remains of which are in the Vatican grottoes. Dalmata and Brenio performed in 1476 a kind of semicircular niche with a sarcophagus standing in it, Roverella's tomb in the church of San Clemente; her Madonna with Angels is one of the best works of the Dalmatian. Paolo Romano sculptured a statue of St. Andrew on Ponte Moli, which, in our opinion, is better executed than his statue of the Apostle Paul on the bridge of Sts. Angels or statues of the apostles Peter and Paul in the cathedral of st. Petra Isaiah da Pisa performed the tomb in the niche of Pope Eugene IV in the church of San Salvatore in Lauro in Rome. Giovanni Dalmata in the 80s. He worked in Hungary for King Matthew Corvin, and in 1509 he executed the beautiful monument to Gianelli in Ancona. Interesting works by Andrea Brenio: new in concept, framed by double pilasters, the Lebretto tomb in the church of Santa Maria Archeli standing in a niche and similar to it, but more strictly framed by the tomb of Alan in the Church of Santa Prassede in Rome belong to the finest Roman sculptural works of the XV century .

Southern Italy, and especially Naples, not wanting to lag behind in the field of visual arts from the new movement, even to a lesser extent than Rome, could do without the importation and borrowing of other artistic forces.

The Florentine sculpture of the early Renaissance was brought to Naples in the first third of the 15th century by Donatello and Michelozzo with their monument to Brancacci; in the last third of this century, Antonio Rossellino and Benedetto da Mayano decorated the Church of Monteoliveto with their exquisite works. Of the 15th century artworks in the Neapolitan plastics area, the triumphal arch near Castel Nuovo, begun under Alfons I and finished under Ferdinand I., is worth mentioning. The authors of the sculptures richly decorating it outside and inside (1455-1459; 1465-1470) are called Pietro da Milano. (until 1473), already known to us by Isaiah da Pisa and Paolo Romano and the students of Donatello - Andrea del Aquila and Antonio Kellino da Pisa, as well as Francesco Laurana. The clearly formed relief of the outer side with the image of the triumph of Alphonse I, as well as the figure-rich, without any particular details on the relief on the inner side of the gate, representing Ferdinand I's investiture in Barletta Cathedral, are sculptured by Pietro da Milano.

In Palermo, the conditions for the development of plastics did not differ significantly from the Neapolitan ones. The new direction was developed in the works of the Lombards Domenico and Antonio Gagini and the efforts of Francesco Laurana. Domenico Hajini (died after 1492), before his relocation to Palermo (1464), who worked in Genoa as a sculptor, performed a beautiful sarcophagus of St. Gandolfo in Polizzi with the noble figure of the saint. Antonello Hajini executed the charming statue of the Madonna (1503) in the cathedral of Palermo. Francesco Laurana, perhaps, was the brother (by Bode's suggestion, his nephew) to the famous architect Luciano Laurana, already known to us as the builder of the urban palace. Both were from Lo Vrana near Zara. Francesco appears in Naples for the first time in 1458 among the sculptors of the triumphal arch, and last mentioned in 1500. He worked twice in France, twice in Naples, from 1468 to 1471 in Palermo. His authentic Neapolitan work is the beautiful Madonna (1474) above the entrance to the small church of Sts. Barbarians. In the south of France, his sculptural decoration of one of the chapels of the church of La Major in Marseille (1476-1481) is the first major creation of the Renaissance on French soil. In Sicily, marble bas-reliefs with the Church Fathers and the Evangelicals in the Church of San Francesco (1468) reveal an even stronger style of the early period of his work, while his Madonns in the Palermo Cathedral and Museum (1469) already show a transition to the dreamy gentleness that he later preferred . Pietro da Milano and Francesco Laurana performed the medals very well. Pietro da Milano's Best Medal depicts the busts of King Rene and his second wife; Francesco Lauran's best work is a medal, on the obverse of which is a portrait of the French king Louis XI, and the flip side very closely resembles the antique coin “Concordia Augusta”.

Painting

In the field of miniatures, which was especially loved by both the popes and the Aragonese kings, the Eternal City can boast that the first Italian book with wood engravings, Cardinal Torquemada’s Meditationes (1467), appeared in it, but the engraver and printer were not Italian and German Ulrich Gan; 33 drawings decorating this book in half-pages and one in the whole page, clearly and sensibly composed, are absolutely German in their clumsy forms.

Более самобытным в этой области представляется нам Неаполь, где книгопечатание ввел, правда, немец Риссингер, но где его преемник Туппо выпустил в 1485 г. издание басен Эзопа с превосходными по технике гравюрами.

Из южноитальянских миниатюристов, находившихся на службе у арагонских королей, выделяются Кола Рабикано и его сын Нардо, украсивший роскошный молитвенник Парижской Национальной библиотеки. Богаты арагонскими рукописями Венская придворная библиотека и библиотека Джеролимини в Неаполе. Особый тип фигуры с большой головой и тяжелыми веками, своеобразное декоративное украшение с канделябрами и putti в обрамлениях и зданиями несколько перегруженной архитектуры на задних планах принадлежат к характерным признакам южноитальянского миниатюрного стиля. Особенно интересны иллюстрированные рукописи из библиотеки Андреа Маттео III, герцога Атри (в Абруццких горах). Миниатюры Реджинальдо Пирамо из Монополи в Апулии (шесть первых миниатюр «Этики» Аристотеля и выходной лист к венскому Сенеке) обнаруживают неоспоримую зависимость их от феррарской школы, учеником которой Реджинальдо, по всей вероятности, и был. Наоборот, другой мастер этих рукописей, Атри, исполнивший миниатюры аристотелевской «Риторики» и Ливия, в Венской библиотеке, примыкает к вышеназванным южноитальянцам, которые работали на арагонский двор.

In the field of wall and easel painting in Rome, thanks to the highly developed artistic sense of his popes, lively activity reigned. We have already seen that almost all the outstanding painters of Tuscany and Central Italy and some of the first-class masters of Northern Italy were invited one by one to Rome to perform large fresco paintings. But almost none of these painters stayed in Rome for a long time, and of the large frescoes created by them only very few reached us. Melozzo da Forli was the only master who lived in Rome long enough to create a semblance of a school here. But if we look for his students and their works, we will meet only one Antoniozzo Romano, who in 1460 adorned the frescoes (not preserved) of Castello in Bracciano; judging by his Madonna in 1488, in the Roman National Gallery, and the "Annunciation", in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minor, it was not a strong master.

And in Naples, in the 15th century, mainly visiting masters of Dutch, Tuscan, Umbrian, and Upper Italian origin worked. The Venetian was Antonio Solario, nicknamed lo-Zingaro (Gypsy), under whose leadership, probably, at the end of the 15th century, 20 large frescoes from the life of St. Benedict in one of the courtyards adjacent to the church of San Severino in Naples. Solario, in any case, knew Umbrian art. The style of these well-composed scenes is vaguely reminiscent of Vittorio Carpaccio. On some frescoes, landscape backgrounds so dominate the plot that they can be called the first absolutely landscape frescoes, and by their nature they can be described as little purely Venetian as the Umbro-Florentine ones.

Fig. 469. Saint Cecilia. Painting in the cathedral of Palermo. With photos of Brodgy

Their original monotony is given by their almost monochrome olive tone, with which the local tones of the clothes harmoniously harmonize.

Painting in Sicily developed somewhat more independently. Messina gave Italy in the person of Antonello one of the innovators of pictorial engineering, but all his talent was revealed in Venice. Another Antonello da Messina, who also called himself Saliba and Girolamo Aldibrandi, wrote The Meeting in the Temple on the main altar of the church of San Niccolò in Messina. In Palermo, from the chaos of the first half of this era, since the last third of the 15th century, original painting began to develop. The fresco “The Triumph of Death”, which is still quite impressive in composition, but nevertheless producing a strong impression, is in the lobby of the former hospital (now barracks) in Palermo, which is recognized as a work of the Dutch school. But undoubtedly, local, Sicilian artists also took part in its execution. On it, Death, in the form of a half-skeleton with a bow in its hand, jumps on a withered horse through a scattering crowd in horror, sending its arrows after it. Palermo painter Tommaso de Vigilia performed in the 80-90-ies. a series of altar images for churches and cathedrals of Palermo. Antonio, or Antonello Crescenzio, was born in 1467 and worked for a considerable part of the XVI century. In Palermo, he was credited with everything that was possible. Probably, it can be identified with that of Antonello from Palermo, who in 1497 wrote “Madonna crowned by two angels” with a wide landscape in the background (now in the Syracuse Museum), and in 1528 a picture with the typical Sicilian dominant rocky landscape in the church of Gancia in Palermo. He is also credited with “St. Cecilia "of the Cathedral of Palermo (Fig. 469), and before that this work was attributed to his pupil Riccardo Quartero. Emotions of faces with elongated noses and not free poses of figures distinguishing Palermo paintings of the 15th century show echoes of beautiful mosaics of the old Byzantine time.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)