Introduction Architecture

In the XV century. the art of the Renaissance, which was a turning point in the cultural development of Europe, was experiencing the greatest flourishing in Italy.

If the visual arts of the Apennine Peninsula at that time so resolutely resurrected the language of classical antiquity even in the field of centenary poetry and science that we can rightly call their creation the Renaissance, then they merged the ancient forms together with their own, which passed through all the Middle Ages. national traditions in a new, inseparable whole. The revival of ancient antiquity is manifested therefore in Italy primarily in architecture, as well as in the frames, ornaments and backgrounds of sculpture and painting. Therefore, in relation to architecture, we are also talking about the early Italian Renaissance of the 15th century. as opposed to the late Renaissance of the sixteenth century.

At this time, the great versatile artists became the head of the artistic movement primarily in Tuscany, which in the spiritual sense remained Italy Italy, and in Tuscany, especially in Florence, where large noble and merchant families from whom the Medici at the end of the XV century were preparing to exchange the stool merchant on the throne of the sovereign, already throughout the century, vied with each other in the patronage of the arts.

When Leon Battista Alberti, an outstanding Florentine scientist and architect, returned in 1435 from the last exile to his hometown, he was pleasantly amazed to see the successes of the “new direction” that great architects, sculptors and painters brought to life here . The masters, whom he pointed out on this subject in his essay on painting (Della pittura), are still recognized as pioneers of the early Florentine Renaissance. As an architect, he called Brunelleschi, whom he himself soon joined, as sculptors Donatello, Ghiberti and Luca della Robbia, as a painter, Masaccio alone, and we argue, as opposed to Janicek's objectionable objection, that Alberti had in mind painter with that name. We will do well if we capture these names in our memory from the very beginning.

A new spirit of the new century, even in Tuscan architecture, no longer erecting Gothic buildings, was useful primarily in the planning of space. The study of the constructive system of ancient architecture, the ancient Greek severity of which was almost completely lost in the remnants of the late Roman era, the less led Florentine masters again to a strict construction that they were not completely aware of the organic regularity of ancient forms after liberation from the Gothic foundations. In general, the plan and the walls covered with pilasters imitating antiques, similar to the decorations set forth, mattered, dimensions and proportions dominated. In particular, the Gothic forms were now replaced by antiquities. Pillars, regardless of pilasters, again began to move into columns for the most part with Attic bases (see Vol. 1, Fig. 330) and capitals, often incomprehensible, but with a taste of executed styles of Corinthian and Ionic, Tuscan-Doric or complex (composite ) style; the cross vaults again turned into flat coverings or domes, the pointed arches again turned into semicircular, which, as a general rule, they began to prefer to beams even for connecting columns. But earlier and most decisively, the imitation of ancient art was manifested in ornaments and ornamental motifs, which, in their light form, have now become inaccurately called arabesques in Italian artistic language. The Late Antique pilaster appears again, decorated inside the frames with leaves and curls going up, often growing from vases. The winged and wingless naked boys of the Hellenistic time, while they have not yet become Christian angels, reappear in the form of cupids, which have a purely decorative meaning. Trophies, candelabra, cornucopias, masks, wreaths, garlands, branches with fruits and flowers, bundles of fruits and ribbons are often depicted in the ancient style, but often also full of new life, noticed directly by nature. It goes without saying that on occasion both the meander and the wavy line come into their own again.

The great masters, whose names were on everyone’s lips, had predecessors in this decorative area who created, although somewhat helplessly, but already at the transition from the 14th to the 15th century, filling the frames in the ancient spirit. It is remarkable that the German Pietro di Giovanni, who served in the service (1386–1402) of the Directorate for the Construction of the Council of Florence, is called the initiator of this trend, who has taken root in the city on the banks of the Arno. In the frames of the eastern door on the south side of the cathedral, naturally executed foliage he decorated with animal figures in the northern humorous spirit and conceived in the ancient spirit, but still poorly processed figures of naked winged boys playing instruments; at the font in the cathedral in Orvieto (1402–1403), he, in collaboration with one comrade, attached already wingless dancing boys to them. On the framing of the eastern door of the northern facade of the Florence Cathedral of Niccolò d'Arezzo (died in 1456), who lived around 1400 in Rome, together with Antonio and Nanni di Banco performed between 1403 and 1409. figures of winged boys playing instruments, in divorces on the inner sides of the shoals, to which wingless cupids correspond to the acanphous leaves of the outer door escarpment. Here the real Renaissance clearly begins.

Fig. 409. The dome of the cathedral in Florence. With photos Alinari

The pioneer of early Italian Renaissance architecture is Filippo Brunelloski (1377–1446). He started a goldsmith, having tested his strength early in sculpture at a competition with Ghiberti and Donatello, and the discovery of the foundations of a picturesque perspective contributed to the success of painting, but his fame was due mainly to works in architecture. The old biographers of Brunelleschi said that at the beginning of the 15th century, he and his friend, the great sculptor Donatello, went to Rome to study and sketch the remains of ancient architecture there; although we will not refute this tradition, we must, together with Fontana, point out the fact that Brunelleschi, in his own buildings, is close to the works of the Tuscan-Romanesque post-antiquity, such as, for example, the baptistery of San Miniato and the church of St. Apostles in Florence (cf. pp. 188–194) than to Roman antiquity.

The first major work of Brunelleschi was the ending of the Gothic building itself - the erection of the dome (fig. 409) over the already-octagonal, with round windows, drum of the Florentine Cathedral. In 1417 he was asked to give his opinion on this dome, the project of which, as Nardini and Fabrizi showed, was finally worked out in 1367. The master, who was assisted by Ghiberty and others, overcame the difficulties of covering an unheard of span. Construction began in 1420, consecration followed in 1436. Eight double vaults to which correspond to eight strong external ribs, abruptly rising upward, tighten the dome under the upper extension topped with a slender pyramid, or a lantern. The artistic property of Brunelleschi is this lantern with its pilasters and semicircular arches, imitating the Ionic railing with balusters (balustrade) on the inner edge of the dome and niche-like extensions on four of the eight sides of the drum. Seen from afar, what the dome is designed for, individual new forms of these parts, fortunately, do not stand out, and according to the general impression, the Brunelleschi dome, without which Florence would not have been Florence, is organically derived from the Gothic cathedral.

The first piece of the early Italian Renaissance was the Brunelleschi shelter for the foundlings (Ospedale degli Innocenti), whose projects he completed as early as 1419. The lower part of the smooth facade develops into one of those galleries with semicircular arches supported by this sleek, smooth columns, which since this time , began to cover the sides of some Florentine squares and numerous courtyards. On the columns lie independently designed capitals in the spirit of the Corinthian, in which Brunelleschi presented preference everywhere. Round pavilions are used to decorate galleries with arches; a flat pediment again has to crown the directly covered windows of the facades; Pilasters, real fluted Corinthian pilasters, supporting a three-part halo of the cornice separating the lower floor from the upper, rise in the corners and next to the portals of the arched gallery. But surprisingly, this three-piece crowning cornice outside, next to the corner pilasters, is released at a right angle to the ground, so that it, like in buildings already mentioned Florentine post-antique era, surrounds the floor with a gallery exactly frame.

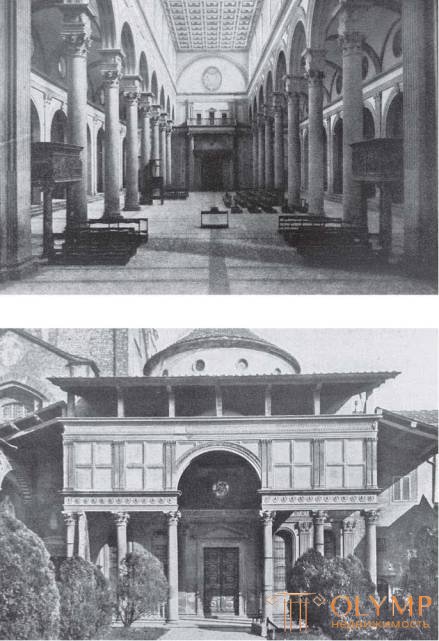

Ecclesiastical buildings of the master, opening the era, before which he did not live, began in 1421 with the construction of a new church of San Lorenzo. First of all, the “old sacristy” was finished, the building with a square base, of a strict nobility, over the four arched walls of which, with the help of the “sails,” rises a twelve-sided fan dome. The church is a three-nave basilica with ancient Christian type columns (Fig. 410, above). The choir and branches of the transept are cut off at right angles. Above the Corinthian columns are tetrahedral extensions that take the heels of the arches, in which the Late Roman samples are repeated (the terms of Diocletian; see Vol. 1, Fig. 507), but they are only half understood. The walls of the side aisles are dissected by Corinthian pilasters with flutes, between which chapels open in the form of low niches with arched tops. The main aisles are covered with a flat ceiling, and the lateral ones with flat domed vaults. The smooth dome over the crosshair, not perceived by the Renaissance, is the work of one of the followers. The clean, strict style of the individual decorations is distributed with a more thrifty hand. The second, richer, and in some respects, and improved repetition of the church of San Lorenzo is the church of Santo Spirito (S.-Spirito) in Florence. The side aisles, where the chapel niches open up to their full height, surround the same with the branches of the transept and the choir, which, of course, provides a richer and more picturesque impression. For the Italian plan, according to which the facade of an oblong church is independent of its core, it is curious that both main churches of Brunelleschi were left without facades.

On the contrary, the Pazzi Chapel (Cappella de'Pazzi; see fig. 410, below) near the S.-Croce church in Florence, a small but complete masterpiece of Brunelleschi, erected between 1430 and 1443, is in full splendor of its elegantly decorated façade. . The six Corinthian columns of the lower floor of the gallery are connected simply by straight beams, just above the gap between the middle columns, the magnificent arch cuts into the upper wall. The upper wall is dissected by double Corinthian pilasters. Between the upper wall and the roof opens a simple gallery with pillars. Inside, the building consists of a middle square, above which a dome rises on a low cylinder, and of low, covered with boxed side portions and a square, covered with a dome altar. Separate forms repeat the forms of the old sacristy of San Lorenzo with noble completeness and calm clarity.

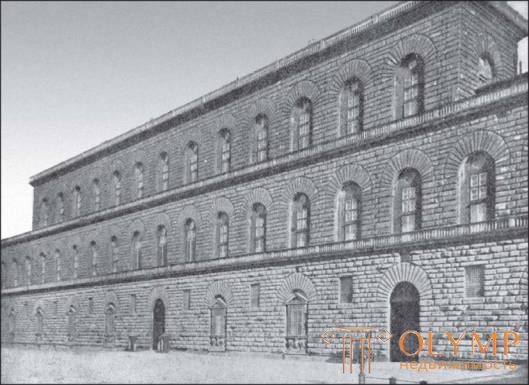

Brunelleschi pointed out new ways in the field of architecture of the Florentine palaces. Architecture in the "rustic" of the plates, strictly turning out their unfinished surfaces, has become a classic palace style of the early Florentine Renaissance. The columns moved primarily to the courtyards. In 1418, Brunelleschi shyly began to disperse with pilasters the powerful external walls of his earliest Palazzo dei Capitani di Parthe Guelph, the main hall of which inside was entirely designed to be decorated with pilasters. His example in this respect did not immediately find an imitator, because in his colossal palazzo Pitti Brunelleschi himself contrasted him with a highly impressive example of pure rusticism. Although conflicting evidence admits some dates due to doubts whether this palace is really the creation of Brunelleschi, for the time being we still adhere to an old tradition, already transmitted by Vasari, that it was designed around 1440 by the great founder of the early Renaissance. Of the widely stretched building, which it is now, Brunelleschi’s masterful work can be considered, of course, only the middle section with seven windows of equal width on all floors (fig. 411), the rest is added later. Only the relationship of the three huge gates of the lower floor, lined with a wedge of rustication, and the seven windows of the upper floors to the surface of the wall, determine the majestic effect of the original construction.

Fig. 410. Filippo Brunelleschi. Interior of the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence (above) and the Pazzi Chapel at the Church of Santa Croce (below)

Fig. 411. Palazzo Pitti in Florence. With photos Alinari

Among the followers of Brunelleschi, Michelozzo di Bartolommeo (1396–1472) stands out, regarding the place and significance of which in the history of art there was a lively exchange of views between Shmarsov, Hans Stegmann, Wolf, Sachs, on the one hand, and Bode, Fabrizi, Gamemuller, on the other. Some glorify Michelozzo to the detriment of Brunelleschi and Donatello, while others value it too low. Michelozzo began his career as a bronze specialist among the employees of Ghiberti and Donatello; as comrade Donatello, performing with him the framing of some tombstones, especially the monument of Cardinal Brancacci in San Angelo and Nilo in Naples (1427), he developed into an architect. As a court architect of the Medici, Michelozzo, from 1435, shifted the center of gravity of his activity to architecture. In certain forms of his buildings, he adhered to the ancient models as strictly and prosaically as Brunelleschi, he adhered to ancient samples, as far as he understood them, but sometimes he was more willing than Brunelleschi to remain in the Gothic tradition. In planning the space, he, on the contrary, was a completely talented master of the new time. Among its earliest buildings (after 1435) belongs the corridor to the sacristy and the Medici Chapel in Santa Croce in Florence. It is here that the Gothic forms are mixed with the imitation of the ancient. The door frames of the corridor doors equipped with gables became exemplary precisely in the sense of their strict antiquity. Between 1437 and 1443 he directed for Cosimo de Medici the construction of the new convent of San Marco. In his graceful cloisters in the Ionic spirit and in the three-nave, supported by 22 columns in the Ionic style of the library hall, we see a craftsman walking boldly on his way. In the facade of the church of San Agostino in Montepulciano, the lower parts of which Schmarsov rightly attributed to Michelozzo, in the lower floor one can see a number of finely made pilasters in the ancient spirit, the first floor gives more Gothic arches, and above the portal - the same raised keel-shaped arch, which the master used already in the eaves of the Brancacci tombstone in Naples. Of the rest of his church buildings, the Portinari chapel at San Evstorgio in Milan should be called, later the masterpiece, the central part of which adjoins Brunelleschi, while the Lombard workers who performed it gave it rich ornaments from garlands of fruits, candelabra, jamb windows and ornaments from terracotta. But all the skills of Michelozzo manifested all the same in the architecture of the palaces. In which year the Medici Palace was built in Florence (now Riccardi), a moot point in the history of art. Contrary to the news that it was started only in 1444, Frey showed that in fact it was already built in the 30s. He would then be the ancient Palazzo Pitti, the further development of which he is usually considered to be, but not the older Palazzo dei Capitani di Parte Guelph of Brunelleschi, behind which the primacy among the Florentine palaces of the early Renaissance will still remain. The beautiful courtyard of the Palazzo Riccardi, from which the composite capital then extended, became a model for the later Florentine palace courtyards. We see the real rusticism in the facade, however, only in the two lower floors. In the second upper floor, along which stretches from above, strongly coming forward, crowning the cornice with teeth and consoles, the already polished plates are turned outwards. The windows with semicircular arches, rising from the gzyms [13], dividing the floors, by their division into two parts and round frames in the arch of the arch remind us of the Middle Ages. By its general appearance, along with the Pitti Palace, this building belongs to the palaces of the early Renaissance, and now still giving the streets of Florence a special imprint. От микелоццовского дворца Медичи в Милане, который в главном этаже, подобно его дворцу Ректората (1464) в Рагузе, имел еще стрельчатые окна, сохранилось лишь немного в Каза Висмаре, не считая богатого портала в античном духе в Археологическом музее. Как бы то ни было, но Микелоццо, участвовавший также в построении Флорентийского собора, должен занять почетное место среди многосторонних мастеров Возрождения в Италии.

As a direct successor to Brunelleschi and Michelozzo, it is necessary to call Giuliano da Mayano (1432–1490), whom Fabriti considered even as a real student of Michelozzo in architecture. He started with carpentry skills, decorated the doors, the backs of the choir seats and the fence with wood inlays. His main works in church architecture are the graceful extensions of the cathedral in San Gimignano (1466), the decoration of the cathedral in Loreto (1479–1486) and the new building of the cathedral in Faenza (1474–1486), in which the square plan of Santo Spirito in Florence with a large the sequence is connected to the complete system of flat domes. Of the secular buildings of Giuliano, it should be noted first of all his share in the Palazzo Quartezi in Florence. The rustic is limited to it by the lower floor, the windows with semicircular arches are decorated with frames in the form of garlands of leaves,and the elegant capitals of the columns in the courtyard are candelabra and dolphins among the foliage. Giuliano was also the builder of the Palazzo Spannokki in Siena, which repeats the style of the Florentine palace of Riccardi, but in better calculated proportions, and in 1485 he erected the beautiful Kapuan gate in Naples, framed by pilasters, whose arch is between two magnificent towers.

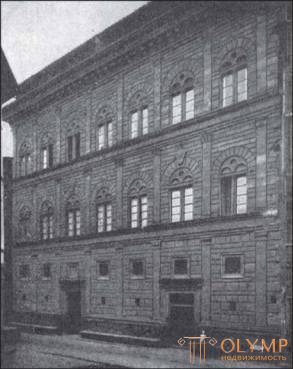

Fig. 412. Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. With photos Alinari

Of the many buildings in Italy, in which the style of Brunelleschi, Michelozzo and Giuliano da Maiano can be seen, but which cannot be attributed to certain masters, we can note here only the charming monastery and Villa Badia (abbey) near Fiesole and the church of Santa Felice perfectly adapted to the slope of the mountain Florence (1457), the longitudinal body of which is covered with a box arch.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) is one of the great creators to whom detailed monographs were dedicated to Julius Meyer, Mancini and Schumacher. Educated with the full brilliance of the humanistic sciences, he himself wrote essays on painting, sculpture and architecture. He belonged to the ancient models even more directly than his contemporaries, but more independently than his successors. In his writings and works, Alberti advocated free creative processing of all samples. He usually provided specialist architects with the execution of his brilliant projects. His first church building, the Church of San Francesco in Rimini, and his first secular building, the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence, were started in 1446. The Gothic chapels of the one-nave church of San Francesco in Rimini he covered with a magnificent architectonics of pilasters, and the unfinished facade in the lower the floor of which, for the first time, semicircular arches are thrown over three-quarter columns, he performed on the model of the arch of Augustus in Rimini. His palazzo Rucellai (Fig. 412) in Florence, the execution of which he handed to Bernardo Rossellino, became the starting point of a new development. Here he contrasted the clean facades with rustiness to the facade, the softened surface of the rustic, which was dissected in all three floors by means of a system of protruding pilasters. On the lower floor he made Doric-Tuscan pilasters according to ancient Roman patterns, on the middle floor - pilasters in a free Ionic style, and on the upper floor - in a completely free Corinthian style. A tasteful lightweight cornice with consoles finishes an elegant building at the top. In Mantua, Alberti erected after 1459, preserved, unfortunately, only in the form of ruins, the church of Sts. Sebastian, which returns to the Greek cross of the Byzantine churches with one middle dome over the crosshair and four identical, overlapped boxed vaults of the side branches. Later in Florence, he was entrusted with the execution of the facade of Santa Maria Novella, the inlay of the lower floor of which was started back in Gothic time, and the facade was completed in 1470. The upper floor, towering only above the middle part of the temple, as in three-basilica basilicas, was divided into pilasters. gives the impression of a fronted facade of an ancient temple with four columns, to which, of course, neither the decorations in the inlaid style nor the middle round window lowered to the border of the upper floor are suitable. The master filled the corners between the lower floor and the slightly narrowed upper one with raised, semi-frontones ending in volutes, which became the prototype of all baroque volutes. Finally, he created the new architectural model, which in the same way was able to evaluate and use only the time of the Baroque, at the end of his life in Sant Andrea in Mantua. The single-nave interior of the temple, in which chapels open, decorated with Corinthian pilasters, is covered with a box-shaped vault, decorated with cassettes. In the high vestibule of the facade with the gable, the scheme of the temple facade for the first time occupies the entire height and width of the building. Alberti’s plans for Nicholas V in Rome, unfortunately, remained unfulfilled. Ettore Bertih, however, also attributed to him the project of the famous Palazzo Cancelleria in Rome, which is a further development of the Palazzo Rucellai.

Among the henchmen Alberti was Bernardo Rossellino (1409–1464), who performed the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. When Nicholas V he was called to lead the construction of the Cathedral of St.. Peter in Rome. Coming from a family of sculptors and architects, he works in Florence mainly as a carver. As an architect, he performs the picturesque facade of the Church of Mercy (Misericordia) in Arezzo, and according to Fabrizi, he also participates in the construction of palaces with the rostics of Neruci and Piccolomini (government palace) in Siena, not yet dissected by pilasters, and is in the service of Pope Pius II ( 1458–1464), whose hometown, Corsignano, he turned by a number of luxurious buildings into the papal city of Pienza. The Cathedral in Pienza represents the three-nave church of the northern-type hall system, but with elevated semicircular arches above the pillars and separate forms in the style of antika. Between the palaces here stands Palazzo Piccolomini, whose facade is closely adjacent to the facade of Palazzo Rucellai in Florence.

The younger Florentine architects of the 15th century were also mostly versatile artists and technicians, whose advice was sought throughout Italy. The most frequently mentioned belongs to Giuliano da Sangallo (1445–1516), who was not only the cathedral architect in Florence, but even by the end of his life, he was for some time the main builder of the cathedral of St. Peter in Rome. The main work of his Giuliano also belongs Quattrocento. Its small Santa Maria delle Carchery in Prato (1484–1495) is charming - a round church with a medium dome, four canopy-covered branches of the cross and with great taste made with friezes, covered with blue and white icing; His octagonal sacristy in Santo Spirito (1488–1492) and the monastery courtyard of Santa Maria Maddalena de'Pazzi (1492–1505) in Florence, whose Ionic capitals freely imitate the late Romans, found at that time in Fiesole, are also highly attractive. Among its palaces, the Gondi Palace in Florence (1490–1498) should be noted above all; the courtyard with columns with Corinthian flower capitals and the picturesquely located staircase belong to the most enchanting creatures of the 15th century. Apparently, the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, which Vasari gave to the sculptor Benedetto da Mayano, should also be attributed to our master. At least, it was documented that Giuliano da Sangallo made a model of this huge building, laid in August 1489. This is the most noble and most spectacular of the private palaces with the rhythms of Italy. He owes his spectacular look to the fashionable main cornice, only in 1500 to the added Simone Pollaiolo, nicknamed Kronaka, who simply copied the ancient Roman cornice on an enlarged scale. So here, at the end of the century, the style of rustic that had independently grown on the soil of the Middle Ages merged with purely antique additions to a new, inseparable whole.

The fact that Simone Kronaka (1454–1508) gave an independent in the field of church architecture, shows the church of Santo Francesco al Monte near Florence, in which he returned to the open rafters. In general, he tastefully distributed smooth pilasters for decoration and introduced flat round gables over the windows, an innovation that found multiple imitations. As he understood the architecture of the palace, it shows a simpler Palazzo Guadagni, the third upper floor of which consists of an open gallery with columns under a far-projecting roof.

Finally, the Florentine should be called Baccio Pontelli (1450–1494), to whom Vasari mistakenly attributed most of the buildings of the early Renaissance in Rome. Its brick churches in the border areas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore in Orciano and Santa Maria della Grazie in Sinigalia, exhibit refined simplicity, turning poverty into dignity.

On the significance of Florentine architects of the 15th century paving the way eloquently testify numerous churches, monasteries and palaces on both sides of the Apennines. In Tuscany, even Siena, thanks to the Florentine palace builders, received the appearance of an almost Florentine city. Among the many-sided artists of Siena, Francesco di Giorgio (from 1439 to 1502), Antonio Federigi (died in 1490) and Giacomo Cozzarelli (1453-1515) stood out as architects. Cozzarella from the church of the monastery of Osservantsa near Siena made a pretty single-nave building with a flat dome, and from Palazzo del Manifico a simple palace, the main attraction of which is elegant forged flag stands. Siena architecture XV century. it was no longer as independent as in the 14th century.

Meanwhile, in the east of Central Italy, the master now appears, under the influence of Alberti, whose fame, thanks to his student Bramante, has spread throughout Italy. This master, about whom Reber, Fabrizi and Calcini wrote, was Luciano Laurana (Zadar, or Vrana, circa 1430–1502). His ancient language of forms exceeded the purity of the language of forms of all his Florentine contemporaries. In his Palazzo Prefetticio in Pesaro (circa 1465) above the ponderous gallery with pillars there is a high upper floor, the decoration of which is entirely concentrated on the huge windows framed here for the first time with ornate pilasters and their crossbars. But the main activity of Laurana launched in Urbino, where he was summoned by the Duke Federigo di Montefeltro. The new parts of the ducal palace, made here by Laurana around 1466, are treasures of the history of art, but, however, innovations, especially in the luxurious courtyard, are here only in the unattainable nobility of proportions and purity of individual forms. Corinthian columns of arched galleries of the lower floor are covered by purely Corinthian wall pilasters of the upper floor with capitals processed according to ancient Roman patterns. The crossbars forming the friezes are decorated with inscriptions, the letters of which, due to their shape and location, give the impression of a strict ornament. The Laurana Palace in Gubbio (1474-1480) also belongs to the finest works of architecture of this kind. It is not surprising that the great Bramante grew up in his eyes in Urbino, who for the first time transferred the style of his teacher to Northern Italy and then in Rome brought him to a high Renaissance.

Sculpture

The history of the Italian sculpture of the XV century. deserves to be written in gold letters. It belongs to the most attractive and most brilliant departments of world history of art.

Numerous threads link Italian sculpture and architecture to this century; Moreover, most of the sculptural works were still inseparable parts of the door frames and wall niches, altars and chairs, organ stands and altar barriers, fountains and, above all, gravestone monuments, which at that time from gravestones on wall consoles of the 14th century became to move to the tombstones of the Quatrocento era (XV century), being placed in our walls, while free-standing monuments, as they were preferred in the north, remained rare, at least in Central Italy. In constructions of this kind, the opportunity was given to develop the ornamentation of the early Renaissance with its clear idealism, quite in the ancient spirit, often presenting a striking contrast with the harsh realism, at that time strongly manifested in the main plastic statues. Many works of small art like statuettes and relief boards, if we trace their history, also turn out to be former components of household items. Works of free round plastic are still rare. As such, it should be noted mainly portrait busts, as independent relief works, this includes medals that were minted, of course, primarily in order to transfer to posterity the memory of famous personalities.

Along with the sculpture in marble, which came out of masonry craftsmanship, and with the sculpture in bronze, which stood in connection with the production of gold products, wooden sculpture in Italy did not enjoy such a spread as in the north, but at this time stucco came forward on the same rights clay sculpture, originating from ceramic production. A special feature of Tuscan ceramic sculpture was its painted tin irrigation. This technique, which came from the east, was often used by Spanish pottery of the middle ages (majolica, from the island of Mallorca). As the Manfred circle showed around 1400, at the Pinakothek in Faenza, it was known in the Faenza ceramic industry (hence the faience) already around the turn of the century, but only Luca della Robbia introduced it around 1435 to a large figure sculpture. Color painting in ceramic sculpture with and without watering and in wooden sculpture, as before, played a major role. Marble statues, however, were painted as a whole only as an exception, usually they were only slightly touched with paint and in some parts they were gilded or left in their light natural color.

According to its content, the Italian plastic of the XV century. It also represents mostly portrait art or takes scenes from the Bible and the lives of the saints. Allegorical and mythological figures, to which we are rather than “genre”, we classify naked boys - (putti), are used in plastics only decoratively or in secondary places, but in small art, namely on the flip side of the medals, they play a certain role . Genre images, however, come across only by chance or are of secondary importance.

The essence of Italian plastics at this time was not an object, but an image method. People are in it in front of us in all their physicality, not only as creatures of flesh and blood, but also with a strong backbone foundation and with all the characteristic features characteristic of them — either beautiful, ugly, old, or young, or calm, or excitement or movement. Naked body, found in plastic except for children's figures only in Adam, Eve, young David and St. Sebastian, still everywhere is felt through the clothes, and in some places it opens. Clothing is no longer depicted for its own sake and is not burdened by unnatural jagged folds, as in northern art (remember Feit Stoos), but only covers the body shapes that it allows to guess and see. In Italian plastic it should look at all this only to the smallest extent as a revival of the ancient heritage, but in the greatest part it should look like a new, own view of nature. Let us add to this the freedom and naturalness of the movements in the depicted actions, a new pictorial form designed for the depth of space, in the relief style used to date along with the old plastic relief style. Already Brunelleschi and Alberti created the foundations of a scientific perspective and taught her: with full awareness of the new acquisition, when finishing architectural and landscape backgrounds on reliefs, they smoothed the boundaries separating painting from sculpture. Again he resurrected the doctrine of proportions, which is shown by Alberti's reasoning, and fifty years later the statements of Pomponius Gavrik in their writings about sculpture.

For practice, these calculations still, of course, had no meaning. Italian sculptors of the early Renaissance stuck into nature with soul and eyes, and since each of them had their own soul and their own eyes, each of them was an artistic person in itself. Strength and grace, rigor and charm appear in the works of different masters, even often in different works of the same masters, now side by side, then in close inner combination.

However, in the sculpture of Tuscany, a new style did not appear immediately. We have already pointed out to the transitional masters Antonio di Banco and Niccolò d'Arezzo. Niccolo d'Arezzo (died in 1456) was so famous that he was attracted to decorate cathedrals not only in Florence, but also in Milan and Venice. His large sculptural works, such as the colossal sitting image of St. Mark in the cathedral and of sv. Luke from Orsanmichele, in the National Museum in Florence, on the schematic folds of their clothes, head numbness and immobility poses only half belong to the new time. Son Antonio Nanni di Banco (about 1373-1420) is already much closer to the new time. The immobility of his group of four saints on Orsanmichele is perhaps deliberate because of the misunderstood antika. The real sculpture of the Renaissance is the figure of St.. Eligiya on the same building; in their everyday life, the reliefs on the pedestals under the aforementioned group are important, and under this figure there are small corner images that introduce us to the stonecutters workshop and the forge.

The great Tuscan masters of transitional times are Jacopo della Querca from Siena and Lorenzo Ghiberti from Florence.

Fig. 413. The gravestone of Hilaria del Carretto, by Jacop della Querca. With photos Alinari

Jacopo della Kvercha (1374–1438) is a master with a strongly pronounced originality, who carried out his artistic intentions mainly through bold body postures and movements of figures, although, of course, he still does not have perfect knowledge of the forms of the body; the tense posture of his figures, reminiscent of the sometimes bold contrast of the two sides of the body, through which Michelangelo aggravates the psychic movements, with Kverch is in essence still the gothic bend of just past tense.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)