Architecture

In continuation of the Hundred Years War, which France waged with England (1339–1453), despite all that Charles V and his brothers did for French artistic life, the leading role of France in Europe in the field of architecture and visual arts gradually ceased. But even in these 100 years, together with Burgundy and the Netherlands, it achieved some success, and from the middle of the 15th century, without directly developing new paths, she again performed interesting artistic endeavors.

French architecture, in which our leaders, along with Gonz and Anlar, were Degio and Gurlitt, during this period remained in some respects more than its neighbors, faithful to the old Gothic style, to their brainchild. At least in the center of France, until that time, they did not dare to remove the supporting arches from the outer sides of the churches, and inside the simple cross vaults to replace those with star-shaped and reticular arches, in which, at last, the organic connection with the beam columns was lost. But the late 15th-century French Gothic follows a direction involving the burdening, complication and branching of beam columns, the elimination of capitals between service columns and the edges of the arch, the modification of geometric cross-cutting ornaments (bindings) into “flaming” notches and all those transformations of arches that led again to the Persian keeled form (see t. 1, fig. 640), they flattened them so much that it was even difficult to recognize them as arches. In this rich fantastical attire of portals and windows with through and jagged ornaments similar to stone lace, France is at some point even at the head of the movement, and it is precisely in French art that the full stylization of natural foliage of pure Gothic ornament in the convex and luxuriant leaves is clearly manifested. And the Gothic had "its baroque and rococo."

Numerous large Gothic churches of France were completed only in the XV century, and there is hardly at least one that would not have any extension in the "flaming" style. The luxurious façade of Saint-Germain-l'Oxperrois, built by Jean Gossel in Paris (1435-1439), is one of the purest creations of this late style. In Rouen, which at that time in some respects led the movement of all France, the transepts of the cathedral and the church of Saint-Ouen now receive their magnificent facades, and Saint-Ouen also receive its tower above the center of the cross. The rich 15th-century French Gothic is most clearly unfolded, as Gurlitt pointed out, in the western facade of the Tours Cathedral.

Of the French churches that arose entirely in the XV century, Saint-Macloo in Rouen, started in 1437 by Pierre Robin, from the base to the top of the tower, however, dating back to the XIX century, gives the impression of a casket for the richest coinage jewels. Entirely built in the "flaming" style of the XV century. the great church of Saint-Nicholas in Port, near Nancy. The church of Sv. Wulfram in Abbeville (after 1488), whose façade is distinguished by almost breathtaking magnificence, and Notre-Dame de d'Epines near Chalon, whose lavish apparel is more restrained. The favorite churches of French criticism are St. Maurice in Lille, which occupies a special place among the churches of the hall system with five naves of equal height, supported by slender columns.

In the Lettner and the barriers of the choir, the celebration of the magnificent French style of the XV century is also noticeable. In the first place is the luxurious Lettner of the cathedral in Albi, rightfully attributed to one of the North French artists and striking with its capricious intricacy. There are also wooden barriers of the choir of 1440 in the church at Le Fraue and granite barriers of a later time at Le Folgohe in Brittany. Through the Normandy, the Dutch influence is manifested here.

In the XV century. France had more luxurious secular buildings, and if there were fewer city halls in it than in the free cities of the Netherlands, then there were more palaces of sovereign and high persons. Although the storms of revolution and the chase of nobility for novelty and leveled here with the earth or changed many houses and palaces of the XV century to unrecognizable alterations and extensions, we still consider some of them.

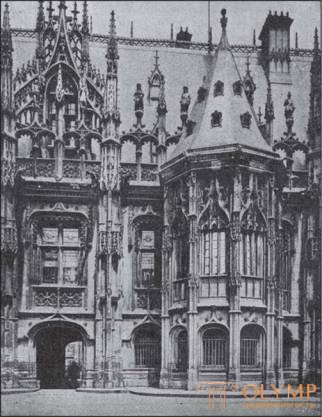

The town halls of Compiègne, Saint-Quentin and Arras, lying on the way from Flanders to Paris, can argue with their sister Flemish in terms of the wealth and pomp of the “flaming” style. To the most elegant secular buildings of the end of this epoch belong the ancient Normandy treasury, now the building of judicial institutions (palais de Justice) in Rouen. In the middle of the graceful eight-window facade, the octagonal tower rises from the ground itself, the pyramidal roof of which, however, is lower than the high main roof (fig. 344). The lower ground floor has completely flattened arches with keel-tops. The windows of the main floor are sealed. Stone slit pillars, gables, window rails and balustrades on the roof make this building a treasure trove of "flaming Gothic".

Fig. 344. Facade of the Chamber of Judicial Establishments in Rouen. According to Gurlitt

Particularly rich in luxurious late gothic French palaces, the Loire region. The castles of Dunois in Beauvancy (1440) and Chateaudenes (1441–1446) and the proud royal castles in Amboise and Blois, of course, make it possible only to feel the former splendor. Excellently preserved, however, the house of Jacques Koura in Bourges and the Hotel Cluny in Paris. Jacques Coeur was the treasurer of Charles XII during the last time of the Hundred Years War. The facade of his house, built by him in 1443 on the shaft of the city of Bourges, is dominated by the middle part, like a tower; in the main floor in this part there is a canopy supported by thin columns, and above it there is a window with a pointed arch and binding cut by flames. During the last decade of this century, Abbot Cluny Jacques d'Amboise built the "hotel" (mansion) of Cluny in Paris, now turned into a famous museum. The most elegant part of the museum is the irregularly shaped entrance courtyard with protruding towers for the stairs, its portals with keel-shaped arches, dormer windows and the lower gallery with pointed arches; the partition of the wall above it with quadrangular windows, however, is almost no longer Gothic. John the Fearless built the Burgonsky castle in Paris; in the decoration of his staircase, which dates back to the beginning of the 15th century, for the first time we see only the now flourishing “woody style” of the late Gothic. The ribs running upwards from the central columns are made in the form of natural woody branches, which spread their arch and leaves along the arch (Fig. 345).

From the late-gothic urban dwelling houses of France, the Norman buildings with a partition wall system in Rouen, Lisieux, Les'Andeli, Caena, Phalese and Quimper meet with a realistic movement of time with their love for the construction truth. These are houses with gable roofs, the upper floors of which, supported by carved corner consoles in the form of consoles, sometimes appear above the lower ones. Especially curious is the house of Jacques Callon in Reims. Hints of phials and keel-shaped arches in a tree are as light as decorations in the form of flowers from crosses (“crucifers”) are good, but for all that, the purpose of partitions is clearly indicated in the building relation!

Fig. 345. Decoration of the stairs of the Burgonian castle in Paris. According to Anlar

In France, in this era, secular architecture also seeks to take primacy from the church.

Convenience for housing and decorative fantasy are the main advantages of this art, which was the fruit of the needs of the time, as P. Vitry said, and showing not decay, but further development. The forms inherent in the Renaissance proper as constituent parts of a transitional, mixed style will keep waiting until the 16th century. Architects XV century. still adhered to the national French art style.

Sculpture

After Kurazho, an outstanding French art connoisseur in the nineteenth century, our knowledge of the history of the development of French sculpture of the fifteenth century. significantly expanded Paul Vitry. He made a clear distinction between the Burgundian-French, Dutch-French and simply French sculpture of this era and at the same time showed that the Renaissance of French art, which borrowed ancient forms from Italy, before 1495, even, actually, before 1515, did not exist yet, and there was a series of easily recognizable decorative works in the Renaissance style of Italian artists working in France.

The first Italian art colony appeared in the second half of the XV century. at the court of King Rene of Anjou. Pietro da Milano and Francesco Laurana, to whom we return, worked here primarily as medalists, and Laurana also as a sculptor in stone. In Marseille after 1475, he executed stone ornaments in the Lazarus Chapel in the main church, in Avignon after 1478 - the large stone altar of the church of Sts. Celestine, now in the church of Saint-Didier. Here, as there, as signs of the early Italian Renaissance, we immediately find imitating antique pilasters with flutes or decorated with arabesques. These pilasters, connected by a straight beam, appear instead of pillars connected by pointed arches. But one can not, however, argue that the style of Lauran independently spread further from southern France.

For the history of French art, a secondary influx of Italian artists and works of art was more important, accomplished only after the rapid conquest of Naples by Charles VIII in 1495, and therefore only during the transition to the XVI century. In the salary lists of content that the king paid to Italian artists, in 1497 the names of the famous architect Fra Giocondo and the equally famous sculptor Guido Madzoni appear; the first remained in France until 1505, and the second until 1516; both of them had an extremely large influence on the introduction of decorations in France through Italian pilasters; the castles on the Loire were the main places where this influence developed. The most ancient pilasters from among the French works that were preserved in cutting and made in Italian or imitatively antique style are the two side pilasters of the famous “Position in the tomb” in Solem (see Fig. 348). This magnificent work of 1496, both in architecture and in forms, is still Gothic, or, better, French. The Italians arrived just in time, Vitry said, in order to add this hors d'oeuvre to the national sculpture along with the date.

The more he avoided the 15th century French art of the temptations of the Italian style, the more readily it, as before, and later, opened its arms to the Burgundian and Flemish influences. French researchers, in complete contrast to the view that Müntz defended, confirmed that this Dutch influence had strengthened French national art, while Italian had weakened it. We have already said that we are not joining the French school of researchers who decided to declare Dutch art to be fundamentally French. The Burgundian-French style, distinguished by its strength, truthfulness, and liveliness with a few heavy forms, spread from its place of origin through Franche-Conte, Provence, Languedoc, even reached Normandy, where, for example, in the church of Sts. Peter in Lisieux has two large embossed images resembling the style of Klaus de Verve, but hardly touched the Ile de France and Champagne at all, and the Loire area with its artistic capital Tours touched only a few shoots, which include the standing Virgin of Beaumont in Archaeological Museum in Tours.

The extent to which the Dutch current, manifested in French sculpture of the 15th century, stood far from the artistic atmosphere of Burgundy, can be traced equally in two directions. One direction is represented by artists and works of art of the first half of the 15th century, leading from the South Dutch masters, such as Pepin de Guy and Andre Boneveu; to another, we rank those artists and those works of art that belong to the new Dutch art of the second half of the 15th century. The disciple of Pepin de Guy Robert Loiselet, the pupil of Andre Bonevo, Jean de Cambrai, was already mentioned before (see Book 4, I, 1). We also met the majestic monument to the duke Jean de Berry, the work of Jean de Cambre, in the cathedral in Bourges, since it was made in the XIV century. Jean de Cambre fulfilled only the recumbent figure of the duke himself. Adorable inspired figures of crying, of which eleven remain in the museum in Bourges, added only in the XV century. Paul Mosselman from South Germany. In the XV century. other works by Jean de Cambrai appear, of which we will here mention only the magnificent tombs of Louis II of Bourbon (died in 1410) and his wife Anna of Auverne (died in 1416) in Souvigny.

The direct Dutch influence, which manifests itself in a large part of France in the second half of the century, is primarily told by the names of numerous Dutch artists who became known from the archives of various French cities, from Rouen to Marseille, from Troyes to Montpellier and from Lyon to Tours. In France, however, there is no shortage of works of art of Dutch origin. The closest way here are carved altars of the purely Dutch type described above, with painted doors or without them, which are preserved, for example, in the churches in Ternan (mid-century) and Ambierlet (1446). But above all, there are some works in stone, with forms, in comparison with the Burgundian works described above, more slender, thin, but no less natural. The most characteristic works include the picturesquely high-relief over the door of the chapel in Amboise with a background filled with trees; on his left side is depicted of sv. Christopher, carrying on his shoulders across the river of the Infant Christ, on the right - St. Hubert, kneeling before a deer with a cross between the horns. Everything here is done extremely truthfully and vitally, with a distinct combination of Dutch and French views.

For the actual French direction of the 15th century, little or not at all affected by the Dutch current, as a continuation of the great 13th century French-Gothic art, the Loire school was mainly important, of which Tour was the focus. This school, without giving up on the naturalism of the new century, subordinated to itself the mannered movements of sculptural works of the 14th century, only in it this naturalism, thanks to French elegance, is relaxed and more balanced.

Some standing female figures best understand this special development for us. The marble statue of Our Lady in the church at Nellier-Pont-Pierre, dating back to 1400, is completely medieval, even with a gothic curvature. It appeared around 1400. Madonna’s painted stone statue on the portal of the Church du Martyre in Riom represents a new French style that is clear, free, calm and graceful. . The transitional link between these two statues is the wooden carving of the Grieving Mother of God in the archaeological museum in Tours, full of deep expression.

This new development can also be traced in the stone lying figures of gravestone monuments. The most remarkable work of the mid-century is the strikingly truthful, finished and, moreover, warmed by the spirit of the new beauty, the marble tombstone of Agnes Sorel (died in 1449) in the choir of the Kolegiat Church in Losch (Fig. 346). Courage and Gonz attributed it to Jacques Morel, but Vitry thoroughly pointed out his purely French character. No earlier than 1490, a splendid stone tombstone of Cyrus de Shaurs in Malicorn (departed Sart) appeared. A recumbent image of a beardless hero with folded raised palms, with all its vitality, distinguished by simplicity and beauty, is very stylishly connected with the Late Gothic sarcophagus.

Fig. 346. Marble tombstone of Agnes Sorel in Losch. By Vitry

Among the most significant works of not only the Loire school, but also the entire French sculpture of the 15th century are the interior decorations of the chapel in the Chateaudian made in 1464. On the fifteen fine columns, the capitals of which consist of half-figures of winged angels in long robes, the same number of painted stone figures towers: the Virgin Mary with the Child, two John, St. Francis, holy women. Performed by various masters, they all are in a certain contradiction with simultaneous Burgundian and Dutch sculptures. The best of them, the Mother of God and Magdalene, are marked by such subtly-felt simplicity and naturalness of posture and drapery, such calm confidence in the performance of heads and hands, such a quiet, brooding charm of facial expressions that almost wonder you ask yourself about the sources of this style. Surely, one cannot talk about Italian influences here, but one cannot also talk about the weakening of the Gothic style, but one must admit that in works of this kind he came from his own source and achieved a clear inner balance.

The metal works of the XV century remained relatively small. Все же мы можем противопоставить друг другу два лучших французских произведения — золотых дел мастерства начала века и бронзового литья конца века. Произведение золотых дел мастерства, подаренное королевой Изабеллой Баварской королю Карлу VI в день нового года (1404), по наследству возвратилось в Баварию и находится в церкви в Альт-Эттинге в Верхней Баварии, прославленное под названием «золотой конек» («das goldene Rossel»). Эта богато украшенная эмалью вещь, несомненно сработанная в Париже, имеет вид алтаря. Наверху на площадке, к которой ведут ступеньки, стоит на коленях король перед Мадонной в ограде из роз, а на земле оруженосец держит королевского коня, сделанного белой эмалью. Натурализм времени Клауса Слютера является здесь перед нами в сочетании с тонким французским вкусом.

Fig. 347. Ангел для флюгера. Медная статуя. По Витри

The brass angel in the castle of Le Loud (Fig. 347) in the Loire region was originally intended for a weather vane and therefore, due to its exaggerated length, it is designed for a view, now it is installed on one of the pillars of the stairs. It is important because it indicates the name of the artist who performed it in 1475, Zhegan Barbe from Lyon. “Dit de Lion,” reads the addition to the name of the artist; therefore, this work was not done in Lyon.

In the Loire region, between Angers and Le Mans, lies the Benedictine abbey of Sol, owning the famous work “The Tombstone” (fig. 348) 1496. In contrast to the tombstones, the most significant of which are in France and the Netherlands in open space, compositions of this kind are installed in niches, and individual figures are made round, as in plastic. A niche in Solem with warriors standing in a recess on each side of the clock is framed by a late-Gothic building, to which, as already mentioned, only at the very end, the pilasters imitating the ancient ones were attached by Italian masters to the bottom left and right. Brave and strong and at the same time very proportional and deliberate, the main striking full-size group is adjacent to the purely French works with which we have already met. Gonza's assumption that Michelle Colomb made it is implausible, but Vitry's assumption that her master is a certain Louis Mourier, we can only consider as a version. Related in style, but more sophisticated are: a charming children's statue of St.. Quirina (Saint-Cyr) in the church of Zharze, near Solem (Fig. 349), and a painted, strictly finished stone head of the Orleans Museum, in a helmet, but bezborodaya. It is wrong to see the head of Joan of Arc, but most likely it is the head of some saint, such as St. Mauritius. These works are irresistibly attracted to the Loire school.

The same school belongs to Michel Colomb - the real head of the XV century French sculpture. It is completely unclear how the master, whose name has been mentioned many times, appears to us as an artistic person only in the 70th year of his life. Colomb was born in 1430 or 1431 in Brittany. Reliable instructions about his stay in Tours, the main place of his activity, have been available only since 1491. He died here between 1512 and 1519. According to his works, it is clear that they belong to the Loire school, which, apparently, is indicated by his whereabouts.

Fig. 349. Infant Saint Cyr. Statue in the church Zharze. By Vitry

Fig. 348. The position in the coffin. Stone relief in the Benedictine abbey of Solem. By Vitry

To consider Colomba together with Vitry without further reflection as a “Gothic” artist seems too bold, as Bode pointed out, but closer than to the Italians, he stands with the Dutch, one can say that he grew out of the noblest traditions of the Middle Ages. With confidence, only three works can be attributed to Colombus, and the earliest of them could have been ordered in 1499. The first is a stylishly realistic and realistic medal (Paris medals office), presented to Louis XII in 1500 when he entered Tours. The second, the master’s main work, is a tombstone, erected by Anna of Breton to her parents, Duke Francis II and Duchess Margaret de Foix, in the cathedral in Nantes, which still adorns it. Jean Perréal, court painter of Charles VIII and Louis XII, made a general project of the monument, he commissioned Colombus to produce luxurious figure sculptures. Marble images of the radiant departed rest side by side on the sarcophagus. Their legs, according to the old custom, rest against the symbolic animals of heraldry - a lion and a greyhound dog. Winged angels in clothes suit headboard.

At the four corners of the sarcophagus are barely associated with it, the life-size figures of medieval virtues — justice, strength, moderation, and wisdom. In contrast to the northern character of this monument, executed between 1502 and 1507. and distinguished by a soft selection of coloring tones, there is its decorative decoration, entrusted by Perreal to the Italian masters of ornamentation that were in France at that time, namely Girolamo da Fiesole. Colomba undoubtedly possesses the main virtues and majestic lying images of the ducal couple, having more common features than one would expect at this time, probably only because satisfactory portraits of both of them were not preserved; but these noble traits are full of life and inner animation, and figures in general of amazing freshness and veracity. On the contrary, the four main virtues (Fig. 350) are individualized coarsely and sharply: they are not at all Italian, but French in dress, posture and facial expression, excellent examples of French national art.

Fig. 350. Michel Colomb. Justice. One of the virtuous figures on the tombstone of Francis II in the cathedral of Nantes. By Vitry

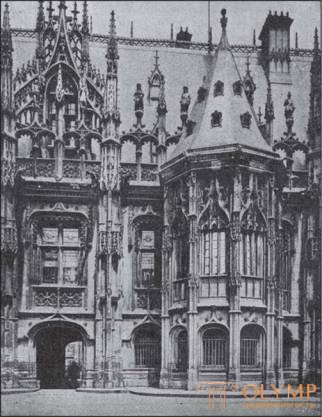

The third reliable work of Colomba is the precious relief of sv. George (fig. 351), executed in 1508–1509. for the castle of Galleon in Paris. He now belongs to the Louvre treasure. The holy knight spears the long neck of the monster. On the left in the mountains, a small figure of a freed princess is kneeling. The simple group is made naturally and animatedly.

To the credible works of Colomb, the surprisingly sophisticated marble image of the Virgin Mary standing in the Louvre, known as the “Virgin of Olives” (castle near Orleans) is closest.

The French sculpture of the 15th century, about which we got at least some idea, is obviously not valued outside France as it deserves it. The French have long had a special talent specifically for sculpture.

Painting

From the surviving data, we can name only four artists found in written sources: Engerrand Sharonton, Nicola Froman, Jean Fouquet and Jean Burdichon. From the north, the Dutch current was growing ever more inexorably; from the south, from Provence, as before, and now the opposite Italian current penetrated, intensified only after the march of Charles VIII to Italy, at the beginning of the 15th century. In the meantime, some French artists, who had themselves visited Italy, made sure that the Dutch shoots did not start on French soil. In the heart of France, in Touraine, the most French of French schools of painting flourished, whose masters retreated before the extreme consequences of Dutch realism. Their language of forms remained more general and gentle than their Flemish and Dutch contemporaries; their letter, which refused to be gilded, was simpler and more beautiful in colors, sometimes more tender, sometimes more smooth, similar to lacquered; The spiritual content of their paintings was usually conveyed vividly and convincingly.

Fig. 351. Michel Colomb. St. George, hitting the dragon. Relief. Marble. By gonzu

Deserving mention of works of true French painting, we could meet most often in frescoes, if they were not preserved so little. Most of all we must regret the loss of the dance of the dead written in 1424 in the tomb of the old monastery of the Minor (aux Innocents) in Paris. It was the oldest dated work, relating, as Seelman showed, to the number of themes known as far back as the fourteenth century. in poetry and in the performance of the memes that delivered to poor mankind, frightened by the devastations that war and plague produced, it was a consolation that before death all people were equal. Representatives of all states, from king to beggar, rush in a hellish round dance interspersed with as many half-rotten skeletons.

Some old French wood engravings from 1485, perhaps, give us one of the images of the Parisian dance of the dead. On the outer fence of the choir of the Chez-Dieu Abbey (Haute-Loire) abbey in the heart of France, another work preserved around 1450 is preserved - the frieze from the dance of the dead, belonging to the most precious treasures of Old French painting. The background is dark red, without a hint of space; the figures in the brown tones performing the dance are captured amazingly. The half-skeletons are inexhaustible in their all-time new grimaces and gestures with which they terrify the victims.

Somewhat older should be the fresco "The Last Judgment" in the cathedral in Albi - a picture remarkable for the portrait features of its figures; the newer is the famous painting of the arches in the chapel of Jacques Kør’s house in Bourges with images of angels in long robes on a blue background. These angels are depicted flying, with flowing long ribbons with inscriptions. Their individually, though sharply written faces, imbued with sweet spiritual bliss, belong to the best that French painting of this time has created.

In the monumental painting on glass, France even retained to some extent a leading role. Technical innovations, on the one hand, in the extensive use of silver yellow new paint (Silbergelb) for stained glass windows, and on the other hand in the application and polishing of not only red, but also blue, green and purple glasses as transitional for modeling, led to to the fact that all large surfaces were freed from the lead adhesions of individual colored pieces. These paints, which could be applied to the glass with a brush, were increased in quantity by means of black solder and silver yellow for the first time only at the end of the 15th century, apart from individual attempts. The old way of placing historical compositions in round frames set in windows was increasingly giving way to a system of luxurious late Gothic style structures with canopies painted silver yellow, in which individual figures stand out against a colored background; in stained glass windows where historical events are told, they usually fill the entire width of individual window fields. Very interesting are the four windows in the north transept of the cathedral in Angers with the image on one of them of its builder, Bishop Jean Michel (1438–1447), kneeling at the foot of the Savior's Cross. Luxurious stained glass windows XV. preserved in the church of Saint-Severen in Paris. Large figures of the holy upper arches testify to the progress that painting on glass of this time has achieved, as well as decorative tools used against the spatial perspective that violates the style of the invasion. In the cathedrals of Bourges, Le Mans and Chalon, one can also trace the development of stained glass windows up to the threshold of the 16th century. Outside it, for example, lead us to the beautiful windows of the church of Montmorency; in one of them we see the giver, Guillaume de Montmorency, kneeling in prayer.

In France, the XV century. carpet weaving also flourished, but, as already noted, it was surpassed at this time by Flemish carpet mats. On the contrary, enamel painting, having come out probably from Limoges, the ancient center of this technique, really went in a new direction. Instead of applying paint like mosaic next to each other, as before, leaving the metal partitions of the tray visible, paint was now applied to the enamel primer with a brush, which they completely covered to form a drawing or painting. Especially loved the paintings in gray tones, reinforced by golden hatching. The most ancient examples of this “painted enamel” (email peint) are paintings from the life of St.. Sebastian on the shrine for the relics in 1479 in the church of S. Sulpice-les-feuilles near Burganath, near Limoges. But this new technique of enamel painting does not mean progress. Subsequently, she led the Limoges workers to the fact that they abandoned their own art in order to imitate mainly engravings on copper of domestic or foreign origin.

History of French wood and copper engravings of the 15th century not yet completely clarified. Until now, individual French wood engravings of this era are almost unknown, and copper was not mentioned at all. The distribution of woodcuts influenced the quality of book illustrations. As Duplessis showed, France accepted independent participation in the manufacture and distribution of books decorated with engravings only from 1480. As scribes and enlumineurs against printers in every field did not vigorously struggle in France, yet the last and with them were engravers uncontrollably conquered one position after another. The oldest printed French books of artistic significance belong to the Dance of the Dead (1485), The World Chronicle (mer des Histoires; 1491) and The Chronicle of the French Kingdom (1497). The most fierce struggle of books with woodcuts against manuscripts with colored pictures was particularly evident in the illustration of the prayer books (Livres d'heures). Both in the painted and in the printed prayer books of France, to which V. von Seidlitz devoted a monograph, the early French book art proved to be very productive. Simon Vostre and Antoine Verard, the French publishers, whose prayer books appeared between 1487 and 1527, became world famous for themselves. Clearly, simply and vividly drawn pictures of these books are also mostly illuminated, that is, painted. Only after 1498 did Vostr begin to add colorful effects to his engravings by shading. Until then, miniaturists were involved in their final decoration, and sometimes the engraver's drawing completely disappeared under the thick colors of the window. It was the books of this kind, which delighted the eyes of the buyer, that accelerated the end of book painting, which finally came in the middle of the 16th century.

Major French artists, whose hands were aimed at new ways, especially easel and book painting in France, first appeared in the middle of the 15th century, and Jean Fouquet, the head of the tour school, was the first to be. He was born in 1415 in Tours; in 1443–1447 He lived in Italy, therefore, before Rogier van der Weyden, and on his return he settled in his hometown, where he died around 1480.

Should we see in miniatures "Bible moralisee", the Paris National Library, the youth work of Fuke, a controversial issue. After his trip to Italy, he appears as a mature artist in miniatures and oil paintings. In his architectural backgrounds, previously by French sculptors and Dutch artists, he preferred the antique and imitating antique columns and pilasters of the early Italian Renaissance, but in his short figures, in carefully written details and lively narrated compositions, no matter how clear they are and are finished according to the forms, Fouquet, as before, and then stands on the northern, Franco-Flemish soil. The naked body is not his specialty, but his landscapes are remarkable for their freshness and clarity.

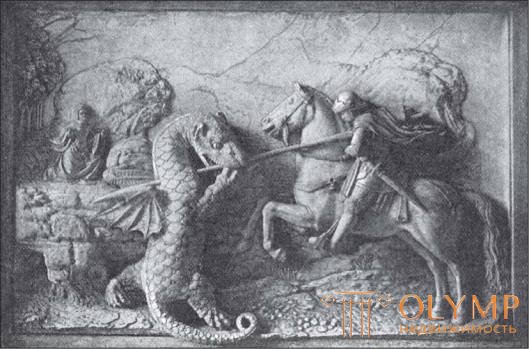

After 1452, Jean Fouquet painted for his patron Etienne Chevalier, the senior chamberlain of the king, an elegant prayer book known from Gruyere’s edition, of which 40 sheets are kept in Chantilly as a French national treasure. Already an adorable first drawing of Etienne Chevalier and his patron of St. Stefan, surrounded by playing angels and praying on her knees in the Renaissance style gallery, shows signs of a master's manner, which is also surprising, for example, in the Adoration of the Magi, The Last Supper, The Apostles and Coronation of the Virgin Mary miniatures , here a triune Divine participates in three identical images (Fig. 352).

In the depiction of the beheading of the head of the Apostle James, he gives something higher in combining the pathetic main act with the rough crowd of people and the radiant landscape. Heures d'Etienne Chevalier was followed by the Grandes Chroniques de France, the Paris National Library, from which at least some of them are rightfully attributed to Fuquet. Around 1469, he drew several miniatures for “The Life of Famous Men and Women” by Boccaccio, in the Munich City Library. The latest miniatures of Fuke also include his drawings to the “Jewish antiquities” of Josephus Flavius and the title page of the “Statutes of the Order of Sts. Michael, in the Paris National Library.

Fig. 352. Jean Fouquet. Coronation of the Virgin Mary. A miniature from the prayer book of Etienne Chevalier in Chantilly. By gruyere

Paintings in oils, Jean Fouquet also quite a lot. His main work, the diptych in Melene, however, is divided into parts. One side, representing the waist image of Our Lady in the crown with the features of Agnes Sorel, the mistress of Charles VIII, is in the Antwerp Museum. The flirtatiousness with which the left breast of the Virgin Mary is exposed is remarkable, which is close to reality, judging by the costumes of that time; the pallor of carnation, as opposed to the angels surrounding the Mother of God in fiery-red hues, is also amazing. The other side, with the image of the Etienne Chevalier from St. Stephen, belongs to the Berlin Museum (Fig. 353). Somewhat outdated

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)