Architecture

England during the XV century. increasingly removed from the continental movement in art. English architecture in the XIV century., During the period of domination of its decorated style, overtook the continent by the improvement of through ornaments in the form of a candle flame and rich net and star-shaped vaults. Now she has provided the continent with the further development of the “flaming” style and other whimsical forms of fantasy, while she herself gave herself to the further development of a clear style for herself, in fact not a Gothic one. If in the previous epoch the stone vault was so small in its construction value in England that even in large cathedrals it was replaced with reproduction in wood, now now horizontal wooden floors with rich carvings or open roofing rafters, delicately decorated with gold and paint, come into play again. Where stone vaults have been preserved, it was in the most important structures that they became flatter and heavier. Fully covered with ribs, like a fan, these vaults with their castle stones often hang down like funnels, so they resemble stalactite formations resembling works of Moorish art. Gothic lancet arches lost their official significance for these surfaces, therefore they sometimes turned into keel arches and sometimes into arches that were so weakly pointed (arches of the Tudors) that, in general, they approached a straight line. Often, they are also covered by straight frames; vertical stone pillars, filled windows and walls, were of predominant importance even in through stone window decorations, but were often connected at a right angle with horizontal cornices and shelves for stability. The fact that even the church towers are now specifically replaced by the spiers with horizontal tops, was only a natural consequence of the development of this style, in which the rich sculpture of the “decorated style” quickly disappeared and which the British themselves call perpendicular style or rectangular . Its geometric correctness deserves praise, but the lack of “rhythmic smoothness” (Degio) and organic life is immediately visible.

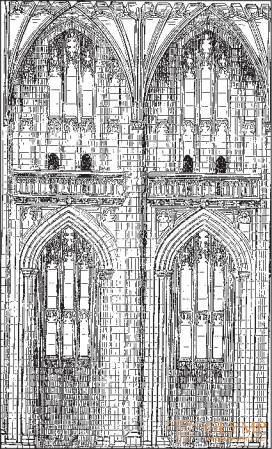

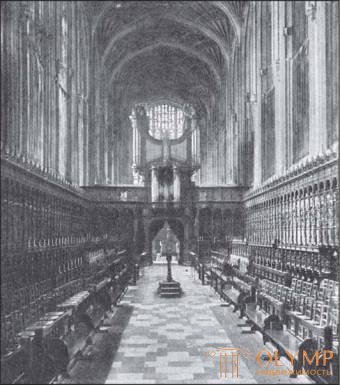

This style developed by the end of the XIV century in the restructuring of the longitudinal buildings of the ancient huge cathedrals in Canterbury (between 1378 and 1411) and Winchester (after 1394); here and there the vertical bars of the windows are already brought to the window arches; in the transformation of the arches and their rectangular framing the longitudinal body in Winchester (Fig. 362), the creation of Bishop William Vikgam, more progressive than Canterbury. The stone fan-shaped arch was formed, however, quite consistently for the first time only in the cloister of the Cathedral in Gloucester (about 1400); richer and most fully is this style in the decoration of the facing stone in the chapel of St.. George in Windsor Castle, in the famous Kings College Chapel in Cambridge (Fig. 363), and above all in the magnificent chapel of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey. Petrified carpentry of the vault with craters stands here in front of us in a magnificent development. We see real carpentry in slightly arched or horizontal wooden ceilings with rich carvings, for example, in the chapel of the college in Winchester, in the Church of the Virgin Mary in Beverly, in the Church of the Holy Trinity in Stratford near Avon, in the churches of the Virgin Mary in Oxford, Cambridge and Bristol In which the English spirit is perfectly reflected.

Fig. 362. Longitudinal hull system in Winchester. By Degio

The perpendicular style was as if created for the secular architecture of England. The construction of Windsor Castle was begun in this style at the end of the XIV century. In the XV century. there were numerous English palaces owned by private individuals and castles of this style. Of the urban buildings, only Guildhall in London (1411–1440) deserves mention, from the outside, of course, later renewed but retaining the wooden ceiling inside. In England, there are many buildings built for research and educational needs for private donations. The College of St. Mary at Winchester refers to buildings made on the orders of Bishop William Wygham. Eton College near Windsor was founded in 1440 by the “holy king” Henry VI. But above all, the buildings of this style are rich in Oxford and Cambridge.

Fig. 363. Interior of the Capella College of Cambridge. From the photo of Frit

The streets of these cities represent an incomparable charm. Bishop William Wikgam added to the building of his Latin school in Winchester the famous university institution - New College (Oxford), whose chapel belongs to the first stage of development of the vertical style, and King Henry VI added his school in Eton to the famous King’s College in Cambridge, where the vertical style is presented in all its glory.

No matter how much one assesses this style, the history of art has given it a place of honor as a style in the spirit of the era and the people.

In Scotland, the late Gothic style has undergone more free processing, typical of popular fantasy. In the huge eastern windows of the renowned church of Abbey Melrose of the first half of the 15th century, still charming in its ruins, we see timid echoes of the English perpendicular style, which was not popular here. The famous chapel in Rosslyn of the second half of the century provides indisputable proof of the artistic eclecticism and love for the artistic freedom of the Scots. In particular, the eastern half is somewhat heavy in its complex pomp of a small building, making fun of all correctness. Equipped with teeth and spikes of arches of various forms that one can think of, the castle stones hanging from the vaults with their funnel-shaped ribs, pillars entwined with spirally garlands of stone flowers, lush stone foliage and rich figure decorations that are everywhere, form a whole, which is striking but at the same time, the embarrassing wealth stands in complete contrast with the sober serenity of the usual English perpendicular style. The Gothic style in the creations of this genus has reached its baroque here too.

Sculpture

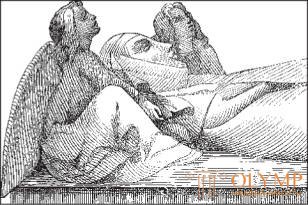

Fig. 364. Tombstone of a noble woman in the Cathedral in Chester. Lubka

Vertical style gradually deprives the English cathedrals of their sculpture decorations. The gravestone sculptures are almost the only English monuments by which we can trace further artistic development. As far as the uninteresting sculpture became already in the reign of Richard II, it shows a double gravestone monument to him and his wife in the Westminster Church. The gilded bronze statues of this monument were performed around 1400 by the London coppersmiths Niko Broker and Godfrey Prest. The beautiful reclining statue of a noble lady in the cathedral in Chester (fig. 364), made no earlier than 1400, bears the imprint of a strictly ideal style of the old time. Small figures crying on the sides and seated angels supporting the beautiful head of the departed point to Burgundian influence. On the contrary, the marble statue of Bishop William Wygham (died in 1404) in his chapel in the Winchester Cathedral was made in the spirit of a realistic century. We see similar progress in the magnificent monuments to Henry IV and his wife (died in 1437) in the Canterbury Cathedral. For the first time, the realism of the century is reflected in a bronze tombstone of the English state husband Boshan, who died in 1439 in Rouen, in the church in Warwick (fig. 365). As coppersmiths and foundry workers who performed between 1442 and 1464. gilded recumbent figure, and here called the London masters. By the end of the 15th century, real works of art in this area appear less and less in England.

Painting

Fig. 365. The interior of the church in Warwick with a copper gravestone statue of Beauchain (the one with the grate). From the photo of Frit

About the English painting of the XV century can be said almost the same as about the painting of the preceding era. Of course, some frescoes have been preserved, but there are no works by which we could trace their further development. Unfortunately, the images “The Dance of the Dead” of the first half of the century, as well as the fresco that adorned the old wall of the cemetery attached to the monastery of St. Paul's in London. Of the 15th century English easel paintings, there are at most several very mediocre royal portraits - for example, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V and Henry VI, in the National Portrait Gallery in London, which correspond to the same, but somewhat better portraits in the royal collection at Windsor Castle and few portraits in private collections.

Were the artists who wrote them, the British, has not yet been established. Pictures of religious content, of which there were probably many in England, destroyed the subsequent Puritan fanaticism. Apparently, in portraiture, as Horace Valpol said, only kings and bishops needed England at that time.

Stained-glass windows of this era are preserved in some churches of the country. In most cases, they depict individual figures of saints under canopies, which, however, being within the boundaries of the perpendicular style, never grow into huge fantastic buildings, like on the continent; there are also several luxurious stained glass windows with numerous individual fields containing biblical scenes or scenes from the lives of the saints. On parts of windows left untouched, colored glass is usually placed, greenish and bluish - in the south, slightly lighter - in the north of the country. The figures, as a rule, are placed under a yellow canopy on a red or blue background and are performed mostly by gray monochrome with only a few color highlights. The windows of the saints in New College, Oxford, with signs of vertical style, date back to the end of the 14th century. The windows of the saints in the school chapel and the cathedral in Winchester - to the XV century. This Winchester style is visible in the windows with a beautiful selection of colors at Merton, Trinity and All-Souls Colleges in Oxford.

Another character is the most famous of the English windows of the beginning of the century, filled with biblical compositions - the eastern window of the cathedral in York (over 20 meters in height), performed after 1405 by glazier John Thornton. Apart from the openwork fields of the arch, in which individual figures stand, this marvel of applied art consists of 117 fields filled with vividly narrated images of the history of human salvation from the creation of the world and the fall to the Last Judgment; the space is not depicted, which gives integrity to the style. By the middle of the XV century. include stained glass windows with which Boshan’s wife decorated his tomb in the church in Warwick (see fig. 365). Noteworthy is the article of the agreement, according to which continental glass should be used, not English, (“Glass of beyond the sea”). The angels singing and playing instruments are completely covered with feathers like birds - a wonderful, though not the only case of this kind of images. Interesting are numerous windows with images of saints and biblical events in the church in Fireford. Some of these images are so vital that in those times when critics did not exist, they considered it possible to attribute them to Dürer.

Manuscripts with miniatures take us to a limited in size, but rich in content world. We consider them, based on the studies of Wagen, Werner and his observations in the British Museum in London. According to the statement of Valpol, that the best English artists of this time were miniaturists, manuscripts with miniatures in types, in colorful harmony and in a strong, sometimes coarse manner of execution do reveal some English peculiarities preserved by them and later, when after 1430 the transition to improved perspective, and after 1450 - to greater similarity in faces, greater flexibility of draperies and better transfer of the landscape. Around 1400, a servant appeared, written by a Benedictine monk John Cyfeerous for Lord Lovely of Tichmersha (died in 1408). The output sheet depicts the artist himself, passing the book to his customer on his knees; The portrait resemblance, clearly visible in the outline of both, shows here also what role these initiating sheets of manuscripts with miniatures played in the development of portrait art. Biblical events are still almost everywhere depicted in the former ideal style, outside of space. The transition to the French-Dutch manner appears for the first time with more force and a more confident perspective in the prayer book of 1430. However, with the Dutch spirit the prayer book of the end of the century is penetrated with calendar pictures that are particularly simple and truthful.

The curious manuscript of The Life of Edmund the Holy by Lidgat, where the golden tree of knowledge is wonderfully depicted in The Fall, under which Adam, Eve and the serpent are made of silver on a bright red background; Also interesting is a prayer book (circa 1460), in which landscape backgrounds alternate with patterned ones. New forms performed by miniatures in books, distinguished by the special, English figures of saints and by the special stylization of floral frames, appear only after the death of Henry VII (1509).

About the state of English painting around 1500, Valpol said: “Although painting reached its heyday then, good taste did not penetrate into our country. And what was he to look for with us? The king was poor, the nobles were humiliated, and who was to encourage talents? ”

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)