Introduction Architecture

Art XV. on both sides of the Alps, it is possible to compare it with an orchard, whose trees are rooted in solid ground, and their knobby branches sway in a clear sky, strewn with ripe and fragrant fruits.

In the field of architecture, which in the north gave way to the leading role of painting and sculpture, Italy differs most sharply from the rest of Europe. Outside the Apennine Peninsula, throughout the XV century, the Gothic style prevailed, although its constructive sequence was gradually subordinated to the desire for free creativity, not only in terms of, but also in the decoration of buildings. In Italy, on the contrary, as early as the previous century, architecture, without giving preference to the Gothic construction, turned to the development of spatial relationships and now, regardless of medieval predecessors, resolutely returned to the language of forms of Ancient Greece and Rome. The revival of ancient antiquity (Renaissance), which was accomplished in literature a century earlier, came to the visual arts primarily in Italy, and it was in architecture (in sculpture and painting - only as ancillary decorations of buildings).

Above the exact definition of the concept of "Renaissance" worked such researchers of the second half of the XIX century, as Jacob Burkgardt, Springer, Münz, Courage, Janiczk, Venturi, Shmarsov, Tode, G. A. Schmidt and Karl Neumann. In contrast to the custom of the third quarter of the nineteenth century. to call all the North and South European art of the fifteenth century an early Renaissance and in opposition to the inclinations of the last decades of the nineteenth century. to move it back to another one and a half or two centuries, it seems to us most appropriate to limit the term "Renaissance" in the history of the visual arts of the fifteenth century. applying it mainly to the reborn Italian forms of Hellenistic-Roman architecture and its decorations. For the art of the XV century. outside of Italy we find it difficult to associate with the word "Renaissance" any definite concept; even in Italy itself, the visual arts, in spite of their casual connections with ancient art, developed in the fifteenth century on the basis of their own medieval past.

With the beginning of the new century, painters and sculptors on both sides of the Alps seemed to have lost their blindfold, making it difficult for them to clearly perceive and reproduce the world of phenomena. Initially, only images made from memory were common, and then those that were made and improved through more accurate observations. Soon, however, artists begin to work straight from nature. The Italian plastic, which won first place, lacked knowledge of anatomy, was compensated by careful observation of a fixed model. Painting in connection with the scientific development of the prospects and the universal use of improved oil paints has gained full possession of its auxiliary means. It is remarkable that advanced oil painting came from the north, which had a more developed sense of pictorial relationships between individual objects, while the development of perspective came from the south, which had a better understanding of space and well subordinated minor parts to the main thing.

On both sides of the Alps, church art still played a leading role. Gradual liberation from the influence of the church - one must keep this in mind - occurred in Italy primarily due to the increasingly free borrowing of fantastic plots from ancient mythology and poetry, while the north turned to portraying mainly folk and everyday life. Despite this, the landscape, no matter how significant his participation in the background of the paintings, was still not achieved complete artistic independence.

Consciousness of dignity among the rulers of the regions and ordinary citizens in connection with the love for real life indicated in this era, the appearance of a portrait image now claimed. XV century. - the beginning of the era of portrait art in Christian nations; one can even say that portrait art, which aims to reproduce the physical and spiritual traits of individuals, was a major part of the entire visual art of this time.

The greater degree of individuality of the artist corresponded to the greater individuality of the depicted person in the portrait: the master and his work became independent artistic phenomena independent of each other. With the increasing differences in the style of works of individual artists, the diversity of artistic outlook among various nations increased. Just as at the Council of Constance (1414–1418) they first voted by nationality, despite the fact that they were voting to one state or another, and along with four nations (German, French, English, and Italian), only the fifth (Spanish) was recognized and in art, various nations first became isolated, and then the cities began to separate. In the general course of art, the national imprint of his best works becomes more and more sharp. At the head of a new direction in art, cities and also individuals, who better understood their time and themselves, become.

The general development of European art in the 15th century will appear before us in its most organic form, if we start to review it from the Franco-German border area, which remained true to its Gothic architecture, then develop it further, and then, at the head of the realistic movement of the new time .

Northern architecture of the XV century. in contrast to the general artistic development, it looks like an old oak tree, growing not in height, but in width. Some of its branches die off, and all of it is magnificently twined with climbing plants.

As the most developed of the building styles in architecture, Gothic survived itself. The outer buttresses system has been lost; lancet arch has undergone numerous modifications, quite often giving way to keeled or even more flat forms; the cross vaults were more and more resolutely replaced with star-shaped and reticular; the beam columns with their service columns, which more often passed into the ribs of the vault, without interrupting the capitals, sometimes, however, again gave way to slender round or octahedral columns. Cut through stone ornaments in the form of a swinging flame of a candle or a fish bubble (see Fig. 240) are so characteristic of the late Gothic style of the continent that the French called this style “flaming” (flamboyant). A stone-bound binding, like a lace lace veil, covered with vimpergi, phials and walls. Sustained pedantry of the “learned” Gothic of the XIII century was eliminated by free creatures of fantasy.

The most magnificent church building in the Netherlands is the Antwerp Cathedral. In the XIV century, only its noble choir was completed. The gently excised service columns of the slender beam pillars of its seven-sectional longitudinal body pass into the ribs of the vault without any intermediation of at least light belts, such as capitals. The inner lateral aisles, however, are still covered by simple cross arches, and only the outer lateral aisles and transept that were started after 1425 have star-shaped or reticular arches. Of the two towers of the facade, the south remained unfinished, while the north during the fifteenth century was built to dizzying heights in very loose forms. The interior of the Antwerp Cathedral with a wide-spread forest of 125 pillars makes an impressive impression, even though you can find flaws in it. Many times they condemned his tower, but, visible at a distance of many miles above the rich city washed by the Scheldt, it is dear to the hearts of many thousands of people with its free forms.

Other previously established Belgian churches, such as the cathedrals of Saint-Michel-e-Güdül in Brussels, St. Bavona in Ghent and St. Rombold in Mechelen, continued to be built during the XV century in the spirit of free Gothic. Of the Belgian buildings belonging entirely to the 15th century, the attention is drawn to the richly decorated basilica with round columns in Diest (after 1416), the cathedral of St. Valtrudy in Mons and the Cathedral of Sts. Petra in Leuven is a three-nave basilica with beam pillars. Her trehariochny Lettner - the best and most luxurious product of Dutch-Gothic small architecture of the XV century.

Fig. 317. Town Hall in Leuven

In the Dutch Netherlands, there are two large churches, covered with stone arches in Utrecht, Dordrecht and Kampen cathedrals - Our Lady of Breda and St. John in 's-Hertogenbosch. The semi-columns of the beam pillars in these churches go directly into the ribs of the vaults. However, most of the churches that have arisen in the green lowlands of Holland, both earlier and later, were built of brick with laying of rows of stone and to this day retained round columns and wooden vaults.

Civil architecture of the Netherlands in the XV century. adjacent to the church.

The rich, although in character, and somewhat church facade of the town hall in Bruges, belonging to the end of the 14th century, already showed us (see Fig. 257) that Flanders did go ahead of other countries in the construction of town halls and that the construction of halls and chambers for the townspeople followed in the footsteps construction of princely palaces. The Town Hall in Brussels, started shortly after 1402 by Jacob van Tienen and completed in 1454 by Jan van Ryuisbruck, is larger and more massive, and its middle tower, under which there are gates, rises to dizzying heights, like a magnificent church tower. We see a more consistent transformation of the Brugge prototype in the beautiful town hall in Leuven (fig. 317), built in 1447–1463. "Urban master-bricklayer" Matthew de Layens, - a building in which a number of features of the 15th century Gothic style are particularly clear. The windows, the pointed arches of which are also framed by keel-shaped arches, do not stretch here, as in Bruges, across all floors, but are located within the boundaries of each of the three floors of the side facade with ten windows, completely dissected by pilasters and windows. Heaped grandeur of the facade is brightened up only by the sequence of its architecture.

In Burgundy, the late Gothic XV century. we meet in secular buildings. In Burgundy, there is the most beautiful of the remaining hospitals - the hospital in Beaune (Beaune), founded in 1443 by the famous Chancellor Nikolai Rolen. The carved canopy above its portal is delightful (Fig. 318), but its courtyard is especially beautiful with wooden galleries and graceful dormer windows covered with wooden gables jutting forward.

Sculpture

Sculptures by Claus Sluter and Klaus de Verve (see fig. 259) at the end of the XIV - beginning of the XV century. conquered not only Burgundy, but also a significant part of France. But since the younger generation of followers of Klaus Slutera consisted mostly of the French, and the Dutch of the XV century. found work within their homeland, now a rather noticeable difference was found between the Burgundian and Dutch schools of plastics.

Among the most successful of these tombstones are monuments to Jacques d'Avens and his wife in S. Jacques, Kolaru de Seklanu (died in 1401), Johann de Bois and Estrash Savary in the Cathedral of Tournai. Short figures with rounded heads, sharply marked folds and wrinkles are by no means beautiful, but important for a realistic direction, which around 1400 was manifested in all types of visual art. In the monumental sculpture of these areas, for example, in large painted stone figures of the Annunciation in the church of Sts. Magdalene in Tourna, you can see all the successes of art, flourished in the XV century, although Meterlink too hastily declared them the creations of the great master Rogier van der Weyden (see Fig. 332), which, however, is known only as a painter.

Written testimonies about sculptors and sculptural works of this time are extremely numerous, especially in Brabant and Flemish Belgium. Local researchers (Marshal, Destre) collected all this documentary information with amazing diligence.

In Bruges around 1400, they again began to finish the sculptural decorations of the town hall. Philip the Good ordered Giloux de Blacker to perform (1434) a monument to his wife Michelie de France, who died in Ghent (1422). This monument, erected in 1540 in the crypt of the Ghent Cathedral, was modeled on the Dijon monument to Karl Smely. However, de Blaker himself performed only an alabaster lying figure, while the small side figures weeping were performed by Tidemann Mas from Bruges. On the side walls of the sarcophagus of Isabella of Bourbon, the second wife of Charles the Bold, whose bronze figure was cast in 1465, historical figures in costumes of the time are placed instead of weeping figures. This sarcophagus is now in a choir tour of the Antwerp Cathedral.

In the years 1495-1501 The Brussels master Peter de Becker (or de Backer) made a monument for his emperor Maximilian I in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges to his wife Maria of Burgundy, who died in 1482. On the marble sarcophagus there rests a bronze gilded amazing statue of the beautiful daughter of Karl Smely. The sarcophagus is conceived in the Gothic style of the Gothic, but its side walls are no longer decorated with weeping figures, but with the coats of arms of the richest heiress. These emblems are luxuriously decorated with enamel, braided with ramifications, like on a family tree, and playing angels are located around them.

Curious carved wooden decorations of altars, painted and gilded. Research by Münzenberger, Basel, van Even, Destre and Rosval shed light on the history of their development. The Dutch works of this kind differ from the modern German ones in that they are divided into fields with niches and, instead of individual large figures of saints, represent biblical events or plots taken from the sacred tradition in groups of round plastics. The walls in each niche converge inside, like a scene, and all empty spaces are covered with extremely rich late Gothic columnar and openwork ornaments.

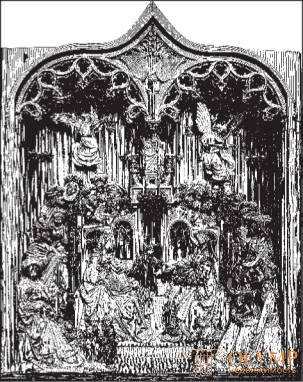

Fig. 319. Altar of Odergem. According to marshal

This style reached its full bloom only in the second half of the 15th century. One of the perfect works of this kind is the beautiful altar icon depicting St. Anne with the Mother of God, the Infant and the entire sacred race, transferred from the church of Odergem to the Brussels Museum of Applied Art (Fig. 319).Another altar image, cut to the order of Claude de Villa and kept in the same museum, with a group representing crying over the body of the Savior, taken from the cross, is no less remarkable. Here we are reminded again of the strict forms of Rogier van der Weyden, but we do not think, like Maeterlinck, that this work belongs to him. Further development of the style can be better traced outside the Netherlands, for example in Sweden, with which the Netherlands have been trading with their own works of this kind since 1480; until that time, preference was given to German works. Interesting are the Brussels carved altars of the Cathedral in Strangnese. One, made in 1480–1500, is a large altar icon of the Passion of the Lord “with the head of a youth”. Figures and clothes are designed in a strict style, "but from under sharply modeled draperies," says Rosval,- the artist gently emphasizes faces, with its characteristic completeness resembling the fine works of his great contemporary - the painter Dirk Bauts. "

Fig. 320. Jacob de Copperflager. Anna of Burgundy. Bronze figure.

Ян Борман — художник, родившийся, быть может, в Лёвене (впервые упоминается между 1470–1520 гг.) и стоявший, очевидно, во главе крупной брюссельской мастерской. Даже самые ранние его алтарные работы, особенно ценившиеся в Северной Германии и Швеции, отличаются большим количеством готических ажурных украшений. Его лучшее произведение — алтарь св. Георгия, перенесенный из Лёвена в Брюссельский музей прикладного искусства, — было закончено в 1495 г. Надпись на большом алтаре с изображением Страстей Господних в приходской церкви Гюстрова в Мекленбурге (опубликован Шли) удостоверяет, что Борману принадлежит его скульптурная часть. Алтарь был поставлен в1522 г. Паскье Борман заведовал мастерской отца до 1539 г. В главных работах Паскье, например резном в алтаре с изображением мученичества братьев Криспина и Криспиниана в церкви св. Вальтруды в Гэрентальсе, в Бельгии, и в огромном алтаре в церкви Богоматери в Ломбэке (слепок в Брюссельском музее), при исполнении фона широко применена живопись, чего фламандские скульпторы XV в. еще избегали, будучи движимы, очевидно, чувством пластичности.

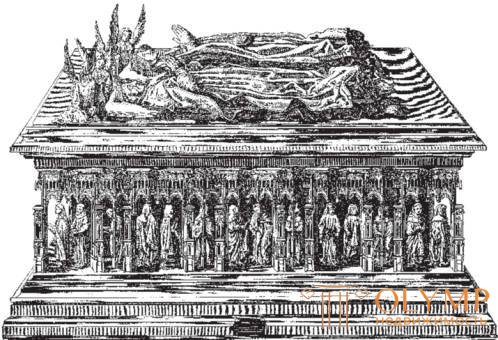

Fig. 321. Tombstone to John the Fearless and Margarita of Bavaria. The work of Klaus de Verve.

In Dijon worked Klaus de Verve (died in 1439) - the great nephew of the great uncle. Only in 1412, under his leadership, the tombstone of Philip the Bold was completed (see Fig. 260). Along with this monument, Klaus de Verve made another tombstone to Duke John the Fearless (died in 1419) and his wife Margaret of Bavaria, also in the Dijon Museum (fig. 321). The mere fact that on the plate of this monument, instead of one, two lying figures are presented, makes it extremely interesting. The master did not live to see the completion of this remarkable work; it was completed only in 1466–1470. Lemaurieu. Klaus de Verve participated in the decorative works for the churches of St.. Bennig in Dijon, the Virgin in Semur and St. Hippolyta in Poligny. The statues of saints in Poligny, distinguished by their magnificent execution, fully depict the art of this master.

Of the other works of Burgundy sculpture, mention should be made of several colored stone groups of the Position in the Coffin, full of strength and expressiveness. In the “Holy Tomb” in Semur we see heavily, with kinks, the falling folds of clothes are a feature that has penetrated into the Burgundian art of this era; however, in the Holy Sepulcher in Tonner, a work of 1453 belonging to brothers Jean Michel and Georges de la Sonnett, we find, in the traditional school, a heap of drapery figures with more even folds and a more spiritualized styling of the grief-filled heads.

Fig. 322. Monument to Philip Po. Probably the work of Lemoature. By gonzu

The Burgundian school usually includes the French masters Jacques Morel from Lyon, to whom Kurazho devoted a monograph, and his nephew and student of this master Antoine Lemoutier. Jacques Morel comprehended his art, obviously, in Lyon. His works are influenced by the works of Klaus Sluter. Morel's youthful work — the tomb of Cardinal Salus in Lyon — has not survived; his work did not reach us either - the tomb of King René of Anjou, former in the Cathedral of Anzher, but preserved, though in a damaged form, his tombstone to Charles I of Bourbon and his wife Agnes of Burgundy in the church of Souvigny near Moulin, the capital of the then independent duchy Bourbon. In this monument (1448–450) all freedom, all the freshness, which the art of the mid-15th century was capable of, affected. Morel died in 1459 in Angers.

Antoine Lemoaturier (died in 1497) was born in Avignon, but he also studied in Burgundy. In 1461 he performed the altar for the church of Sts. Petra in Avignon, and between 1466 and 1470. completed the aforementioned monument to John the Fearless in the Carthusian monastery in Dijon. The powerful gravestone monument to Philip Po, completed around 1493, is attributed to Lemoaturier (Fig. 322). This stone-painted monument, located in the Louvre, brilliantly ends the development of Burgundian sculpture in the XV century. The mourners are no longer placed on the walls of the sarcophagus, but are independent, full-sized figures of people full-sized, carrying a board with the deceased on their shoulders.

Painting

In the XV century, churches, castles, town halls and houses of the townspeople still lacked wall paintings, but the dampness of the coastal climate destroyed it, with the exception of a few remnants, and caused the inhabitants of the Netherlands to love decorating the walls, preferably with warm carpets, which, surpassing Paris, supplied the whole world first with Arras, and then with Brussels. Netherlands painting on glass, the study of which Lewi was engaged, began to develop independently only in the 16th century. Consideration of minor remains of stained glass windows of the XV century. would make our review of the general art movement more difficult.

At the head of this pleiad of masters are two brothers Hubert and Jan (Johann) van Eyck. The place of their birth, Maaseik in the province of Limburg, belongs to the region of pure South German. Jan van Eyck readily recognized his South German origin, for example, in the inscription “Als ich kan” (“As I can do it”), with which he supplied his paintings. It is assumed that Hubert was born about 1366, and Jan about 1390. Hubert died in 1426 while working on his Gents masterpiece. In 1425, in Bruges Yang entered the service of the Duke of Burgundy Philip the Good, in 1427-1429. visited Spain and Portugal and in 1430 settled in Bruges, where, according to the discovery made by Wil in 1904, he died at the end of June 1441.

Fig. 323. The return of the Duke William on the seashore of Holland. Thumbnail from the Turin prayer book. By Durieu

It is established that Hubert van Eyck was the teacher of his younger brother. But where Hubert himself drew his art, in which all the artistic skills of that time were concentrated, is unknown. Apparently, this was the art of the Limburg region, through which the Meuse flows. Without abandoning the Flemish French acquisitions, it reached a level here that could only be dreamed of. No wonder Maastricht was considered in the Middle Ages together with Cologne as the center of painting! The first Duchy of Burgundy Philip the Bold commissioned Jan van Gasselt of Limburg to perform the altarpiece in Gent, and master Paul from Limburg and his brothers sang the oldest and best part of the Duke of Berry prayer in 1410 — an illustrated manuscript that Delil called “ roi des livres d'Heures. " In the biblical scenes of this manuscript, which is stored in the castle of Chantilly, the Italian features of transitional time are visible. In the drawings of the calendar, on which castles of Paris rise in the radiant distance, we encounter hitherto unprecedented realism. It is impossible to deny that the life-giving air of Paris contributed to the development of book painting, but in contrast to Boucho and Dvořák we remain convinced that its origin is German-Dutch. The French connoisseur, Count Paul Durrier, considered executed for about 1417, also for the Duke of Berry, the prayer book "Livre d'Heures de Turin", most of which, unfortunately, burned down in the Turin National Library in 1904 (several sheets remained, for example, meeting of Trivulchi, in Milan), the work of Hubert van Eyck! And indeed the sheets of this prayer book are surprisingly close to the works of his school. Such drawings as “The Ascension of the Virgins to the Lamb on the Hill” or “The Return of the Duke William on the Shore of Holland” should belong, at least, to the workshop of the van Eyck brothers (Fig. 323).

Fig. 324. God the Father, Mary and John. Fragment of the altar folding work of the brothers van Eyck. With photos of Brookman

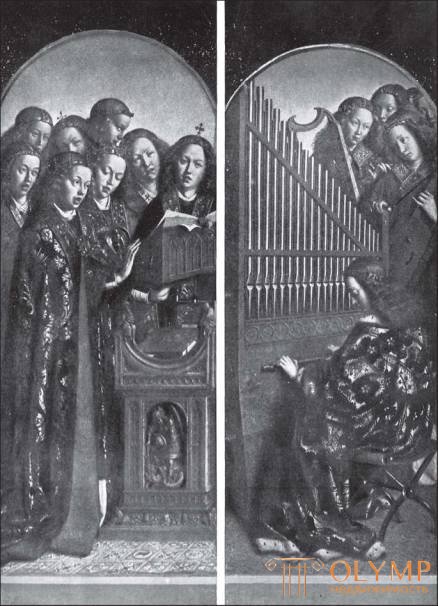

Fig. 325. Groups of angels. Fragment of the altar folding work of the brothers van Eyck. From the photo Ganfshtenglya

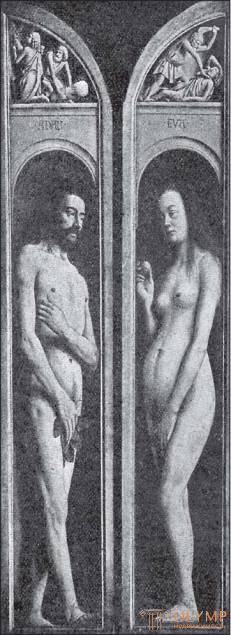

Fig. 326. Adam and Eve. Fragment of the altar folding work of the brothers van Eyck. With photos of Brookman

Finally, the bottom row of planks (in the Berlin Museum) is dedicated to the worship of the Lamb from the Apocalypse. Through all the five boards under the sky stretches a luxurious rocky landscape with lush greenery, southern vegetation, with rocks and hills covered with trees and flowers. On the distant horizon, as in the Brussels manuscript of St. Augustine described above (see Prince 4, 3), the towers and the roofs of distant cities rise in the clear air. In the middle, on the altar, surrounded by kneeling winged angels in long robes, stands the Lamb, the symbol of the Savior. Ahead, on the left, numerous heroes of the Old, and on the right, equally numerous representatives of the New Testament form the right groups. On the twin doors, closer to the foreground, through the wild rocky gorges and flowering valleys, new crowds are crowded. The arrangement of the figures was done at the request of the ancient texts: on the left — the horsemen, on the right — the travelers, on the left — the soldiers of Christ (fig. 327) and righteous judges, on the right — the holy pilgrims with the giant Christopher in front of them (fig. 328) and the holy hermits, in front of which go Paul and Anthony. What a mass of strong images in all these groups! If within all the lower ranks of the saints there is some inconsistency in the aerial and linear perspective, yet the artists have so successfully, with such a true feeling, compared them, that the whole work is an amazing work, in which they merge into one

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)