Middle Italian architecture of the 16th century

1. Creativity of the Renaissance

The grandeur of the buildings of the high Renaissance that flourished in Rome led by itself to the strengthening of the walls and pillars, to the preference of domes, barrel vaults and pillars, as well as to the strengthening and simplification of individual decorations. Hand in hand with this went the clearer use of the ancient language of forms, partly due to a better understanding of the Roman writer about the architecture of Vitruvius, in whose honor the Vitruvian Academy was founded in Rome in 1542, and partly with excavations and measurements of the ruins of Roman buildings. This was facilitated by a new, more sophisticated taste for proportionality and the rhythm of dismemberment, to the nobility of the proportions themselves, based on the laws of nature, such as on the “golden section” embodied in the human body, or on the geometric construction of repeating or alternating mathematically identical, but different sizes of the main forms, like those that Tirsch made public.

In the structure of the churches in the short period of flowering dominated the central, domed type, at the same time receiving a new life in Constantinople. In the palaces, the main parts still represented a courtyard with columns turned into pillars and semicolumns, and the facade, which at first was very vigorously dissected by sharply protruding, often paired semi-columns, but soon threw off this fake forest of columnar architecture, to give the impression only by the ratio of individual floors and the distribution of windows, niches and doors. The windows, doors and niches began to be framed with semi-columns or pilasters and covered with flat triangular or semicircular gables from above. Of the orders of the columns, Tuscan or Roman Doric (Greek Doric was not known) was at one time preferred to another, as a result of which the leafy parts, apart from the garlands in the decoration of friezes, almost completely disappeared from the architectural ornamentation. Everything came to a calm balance and beauty of the masses.

Of the transitional masters, Bramante was not only the greatest who made all the decisive steps, but also the oldest. Giuliano da Sangallo himself, familiar to us among the masters of the early Renaissance, was younger than him. But the later position of Giuliano in the construction of the Cathedral of St.. Peter and his close relationship with Michelangelo show that he himself went through a transitional stage to a high Renaissance, which is also confirmed by his numerous drawings studied by Fabrizi and located in Palazzo Barberini in Rome, in the city library in Steen and in the Uffizi in Florence. He sketched a number of ancient Roman buildings and composed a number of projects never carried out for luxurious buildings, such as the Medici Palace in Rome and the facade of San Lorenzo in Florence. Redtenbacher even says that Giuliano, having jumped from the early Renaissance over the high, went straight to the late Renaissance. There is no doubt, however, that only his brother Antonio da Sangallo the Elder (1455–1534) reached the high renaissance, since his church of San Biagio in Moptepulciano, of a cruciform dome type, sustained in the lower floor outside and inside in the Doric style, is a freer repetition such as the Madonna-Carchery Giuliano church in Prato, and the longitudinal body of the Church of the Annunciation in Arezzo, noble and seasoned in Corinthian style, signifies the transition from a columnar structure to a building with pillars. The third master of the transitional style should be the famous sculptor Andrea Sansovino (1460–1529), a pupil of Giuliano in architecture at the end of the 15th century, who transferred the Florentine early Renaissance to Portugal. At the beginning of the high Renaissance, he decorated his hometown of Monte Sansovino with Corinthian and Ionic galleries, after 1511 built in Rome for Cardinal Antonio del Monte a high Renaissance palace in front of Porta del Popolo and was finally called to Loreto to continue building the cathedral, whose dome was erected by Giuliano da Sangallo in the year 1500

Fig. 17. Portrait of Baldassare Peruzzi by Rafael

2. Antonio da Sangallo Junior

Giulio Pippi, nicknamed Giulio Romano (1492–1546), became a disciple of Raphael also in architecture. Of the Roman palaces of his palace Maccarani is dismembered on the model of the later palaces of Bramante and Raphael. He decided more sharply in Mantua, where he moved in 1525. His own house here is a simple rustic building, with flat arched gables on the windows; its decoration of the hall in the palace of the Dukes of Gonzaga is magnificent; the impression of something rude and strong is made by the Palazzo del Te, the far-flung Ducal castle of the country, whose rustic armor does not seem to soften by Doric pilasters. The most beautiful architectural creation of a high Renaissance is considered to be a large gallery, open to the garden side, with its wide semicircular spans, between which a motive that quickly became a favorite, each pair of columns connected by a short straight crowning cornice. The longitudinal case of the cathedral in Mantua, rich in columns, also looks classic, but the original longitudinal case of San Benedetto, the foundations of the middle nave of which repeat the already mentioned arched spans motif with double columns.

Fig. 18. Portrait of Giulio Romano (1492–1546)

Turning to central Italy, we see how in Pesaro, under the hands of the painter Girolamo Genga (1476–1551), as an architect who continued the direction of Lovran, but in the spirit of Bramante, not only does the church of John the Baptist appear, covered with barrel vaults, but also grow magnificent extensions of the Palazzo Prefetticio Lovran, but more importantly, on the mountainside is Villa Imperiale, a magnificent manor in the style of high Renaissance, which, thanks to the research of Tode, Gronau and Patzak, should be placed in the center of the Italian Pitchfork golden time. Especially typical are the internal pictorial decorations of this villa as a special kind of internal pictorial scenery, pushing forward the promising spaces, and at the same time as the ancestors of decorative Italian landscape painting, such as Peruzzi decorations in one of the upper halls of the Villa Farnesina in Rome.

In Florence, the buildings by Baccio d'Agnolo Baloni (1462–1548) especially convince of how long the local spirit of the early Renaissance lived in more perfect forms of the highest heyday. Such, for example, is his Bartolini Palace, dissected only by niches and windows with semicircular segments and triangular gables.

The Brahmint High Renaissance is expanding its wings in a number of buildings of the mid-Italian architecture, which we cannot list the builders. The type of central domed temples belongs to the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione in Todi (1508–1524). In terms of terms, it has four equally rounded branches of the cross, and the outside is more successfully dissected than inside. On the contrary, the church of the Madonna in Montjovino near Panikale (1524–1526) only inside reaches full completeness. Of the longitudinal churches of this style, the cathedral in Foligno is distinguished by the purity of the plan of the six-square Latin cross. Of the palaces of this kind, the Palazzo Uguchchoni in Florence, previously considered as Rafael, is spreading over the first floor, which has been divided by rusticism, two more floors, the lower one, decorated with Ionic, and the upper one - Corinthian double columns. The Palazzo Spada in Rome is important, since it undoubtedly adjoins the Palazzo Branconi of Raphael. The ground floor is rustic, but in the upper floors the architectonic dismemberment is replaced by plastic ornaments, bundles of fruits and niches with gables and caryatids. It was here that the transformation of taste was announced.

Fig. 19. Madonna’s Church in Orto

3. Italian architecture of the XVI century

The Italian architecture of the second half of the XVI century, or even before 1580, is considered by some (for example, Yak. Burkgardt and Durm) for the time of the great theorists, by others (for example, Korn. Gurlitt) for the late Renaissance, while Wölfflin sought to show that “Late Renaissance” could be suitable for upper Italy, but not for Rome, where this movement, under the influence of Michelangelo, immediately turned into baroque style. Rigl's work adjoins the same view, but Schmarsov found it necessary to establish that the Baroque style, commonly called “picturesque,” at the first time of its development, which we are interested in, should be called rather plastic because of its desire for a more unifying, organically closed division of surfaces and propensity to develop them in height (the well-known "aspiration up").

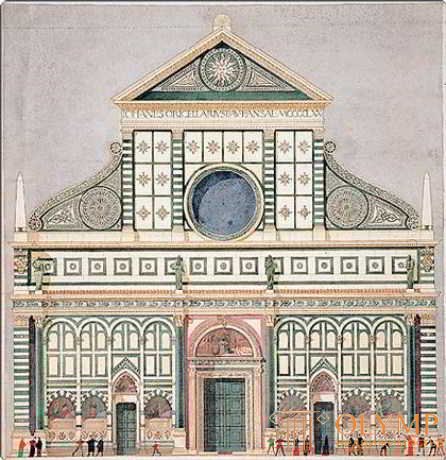

In the Roman church architecture, buildings of the central type again became longitudinal, with a high dome at the site of the medieval “medium cross”, mainly single-room buildings of the hall system, with chapels on the longitudinal sides framed by a system of pilasters and arches that open into a high hall covered with barrel arches, decorated cassettes. The plan of the lower base was simplified with the aim of combining it. Only the mass of the walls as such is animated by retreating back and protruding parts. Outside, except for the dome, only a two-tier facade with a pediment, dissected by pilasters, achieved artistic expression. The narrower upper floor, which soon grew independently above the middle nave, following the example of Santa Maria Novella according to Florence, began to connect with a wider first floor in various sideways.

Fig. 20. Santa Maria Novella of Florence

The uneasiness of the facades, the slogan of which is strength and movement, is tempered by the calm of the high dome. All the individual partitions closer than before, connected to the body of the walls, which seem to be exactly molded from a homogeneous mass. Inside the temples, columns and semi-columns completely give way to pillars with pilasters or beam pilasters, and outside, not to mention the columns of portals, powerful pilasters, which are connected to the walls by means of retreating half-pilasters. Doric warrant gradually gives way to Corinthian and composite. Akanf of capitals gradually decomposes and rounds out beyond recognition. The profiles of the plinths and cornices acquire curved and rounded parts; The edges of the stone panels and the cartouche frame (cartocci), which, together with the garlands and bundles of fruit, have become the main elements of the baroque ornament, begin to bend and curl so gently as if it were an easily flowing fluid. Side columns or pilasters of windows with gables and niches sometimes turn, like in the library of Laurentian Michelangelo, into pillars that thin down towards the bottom like germs or completely disappear to give room to consoles under gables. In this case, flat, arcuate gables are sometimes fancifully dispersed, flat triangular gables often not only in their main lines, but also open up in the upper part and get a break. “Striving upwards” is answered by striving towards the center, which is getting richer and richer and comes to the fore with the help of a powerfully dissected and outstanding forward portal.

The Roman palaces of this first Baroque time differ from the high Renaissance palaces in particular by their facades, which now, if you leave aside the main entrance, are almost never divided by pilasters or semi-columns, as they are often covered with whole lime, while doors, windows and niches experiencing the same changes as church facades. Free and picturesque turned country and on the nearby mountains of the villa. Already the need to adapt to the landscape of the area and to the breakdown of the gardens led to a more free planning, which was often the source of their special charm. It was the time when many of those famous villas in the Rome area were built, which now, after more than three hundred years of life in their gardens, seem even more beautiful than they could have seemed then.

4. The formation of a new style

The architects who took part in the emergence of a new style in Rome, for the most part were not Roman natives, and not even Middle Italian, but northern Italian, in Rome, however, who developed their abilities. Among these Roman architects, the “great theorists” belonged, by the way, to Giacomo Barozzi from Vignola of Modena (1507–1573; Willich's book), whose essay on the “five” orders of columns (1560) began to give tone in the sense of following Vitruvius, although Vignola himself, as a pupil of Michelangelo and as his successor in the construction of Peter’s Cathedral (1564–1573), belonged to the masters who took part in the birth of the free baroque style. Among his early Roman enterprises (starting from 1550) was his participation in the construction of the palace of Pope Julius III "Viña", strongly limited by Vasari, who attributed to himself a large share of participation.

Ученик Виньолы Джакомо делла Порта, по Бальоне римлянин (1564–1608), приобрел вечную славу как строитель собора св. Петра с 1573 г. тем, что закончил выполнение главного купола Микеланджело, наружных очертаний которого он вовсе не изменил, как это утверждали. Его фасад церкви Санта Катерина де Фунари (1564) может еще считаться почти чистым произведением высокого ренессанса, а фасад его церкви Иисуса, построенной (после 1573 г.) Виньолой, в деталях производит впечатление не более барочного, чем проект самого Виньолы. Характерны мощные соединительные волюты между этажами, характерно двойное обрамление главной двери, двойным пилястрам которой отвечает также двойной, снаружи закругленный, а внутри треугольный плоский фронтон; характерны, наконец, также более богатые извивы карниза. Его маленькая церковь Сан Мартино аи Монти (1579) в своей целомудренной крепости стоит еще почти на классической почве. Но его фасад Сан Луиджи де Франчези (1589) показывает выразительное «стремление ввысь» барокко. Верхний этаж, занимающий всю ширину нижнего, не только выше последнего, но поднимается в пышном великолепии даже над кровлей церкви.

5. The formation of Martino Lungi

The main pupil of Giacomo della Porta is Lombardo Martino Lungi, who erected the tower of the senators' palace on the Capitol in 1579 and only by the end of the century did the most masterful work of his work - the church of Santa Maria della Valicella, whose form language is based on the prescriptions and the example of Vignola. Its main secular building is the Palazzo Borghese (since 1590), whose courtyard with arched spans, again lying on double columns, below the Doric, above the Ionic, still unfolds all the charm of a high Renaissance. The imitator of Vignola is Roman Pietro-Paolo Olivieri (1551–1599). His beautiful church, Sant Andrea della Valle, is directly adjacent to the church of Jesus Vignola. Opponents of this school are such masters as the Neapolitan Pirro Ligorio (died in 1580), the creator of Villa Pia (1560), built in Raphael style in the Vatican Gardens, then Annibale Lippi, the builder crowned by the tower of Villa Medici on Monte Pincio (1590 ), the garden side of which has its rich gallery with double Ionic columns, a tall semi-circular arch divided in the middle, and a wealth of decorations distributed across all floors, stands in intentional contrast with another very simple side facing the street.

Fig. 21. Villa Pia (1560)

At the end of this row of architects stands Domenico Fontana from Lake Como (1543–1607), the assistant to Giacomo della Porta at the end of the dome of the cathedral of Sts. Peter, on top of which he added in 1598 the lantern of Michelangelo. He thus belonged to the Roman successors to Michelangelo, Vignola and della Porta, and in their direction with a few cold grandeur he performed a number of magnificent buildings. Known for its ascending domed quadrangular chapel (del Presepio) during Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, its two-story gallery (loggia) in the Lateran is famous, with arcades that lay down on the Tuscan pilasters, and on the top on the Corinthians, equipped with double pilasters in the corners, the architecture is attractive of the lower base for the Aqua Paola fountain, undoubtedly designed by his elder brother Giovanni Fontana (1540–1614), resembling a triumphal arch and, in contrast to the plastically conceived delta Porta fountains, opening a series of architectural fountains of Rome. Finally, Fontana was invited to participate in the buildings of all the big palaces in Rome, which were then erected or completed in the Vatican, the Lateran and the Quirinale, finally, even (1600) in the royal castle in Naples. However, no matter how powerful all these buildings are, in artistic terms they do not inspire us. Rigl correctly pointed out that the “family from Lake Como” - Lungi and Fontana, with their classical inclinations, made some stagnation in the baroque movement.

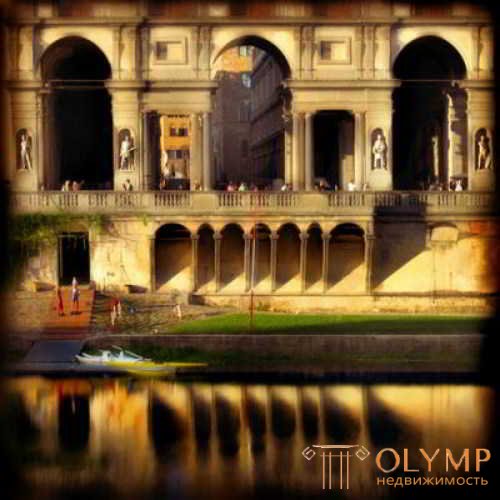

Outside Rome, in central Italy, Florence is especially important for further development. Here Bartolommeo Ammanati (1511–1592), who had joined Vignola in Rome since 1550, and from 1556 worked again in Florence, built the wonderful three-span bridge “della Trinita” and apart from many palaces that hit their windows freely and strictly together invented in the forms of early baroque, it was created, first of all, by the impressive garden facade of the Palazzo Pitti, which produces a somewhat heavy, but at the same time extremely strong impression with its rustic design, located above the semi-columns of both floors. Here, then, the true disciple of Michelangelo, Giorgio Vasari of Arezzo (1511–1574), compiler of famous artist biographies (from 1560), erected the classic Uffizi building with its magnificent gallery on Doric pillars and pillars, a high arch opening onto the river Arno. Artistically valuable is also the Abbadia de Kassinenzie church (1550), built and richly decorated with columns in the spirit characteristic of Vasari in his hometown Arezzo. In Florence, his direction continued by Bernardo Buontalenti (1536–1608). The value of Buontalenti for the Baroque style in Florence was outlined by Gurlitt. Everywhere he seeks to replace the old separate forms with refined forms of his own invention. Already in the Uffizi there are windows, the rounded flat gables of which are divided in half and connected in the opposite direction with the bases of the perpendiculars in the middle. In Palazzo Nonfinito (now the building of the telegraph) there are capitals made up of hanging cloths and belts that enclose masks; the most amazing quirks of Buontalenti never produce a strange impression, but on the contrary, act as something very subtle, imbued with individual force. The great influence they had on Florence clearly appears only in the seventeenth century.

Fig. 22. Palazzo Nonfinito

Middle Italian architecture of the 16th century

1. The development of Central Italian sculpture

The development of the sculpture of the XVI century from the forms of the XV century was carried out in the same direction as in other arts. The new direction of the sculptors, however, not to mention the only, superior to all, Michelangelo, was not as clear as that of architects and painters. The light shed by the creatures of Buonarroti left all other sculptors in the shadow or blinded them. High renaissance to the strengthening of forms in sculpture, dealing mainly with the image of a person as such, very easily led to the removal from the norms of nature; the desire to simplify forms, however, hardly put up with the desire to express sharper contrasts in the directions of movements; the desire to isolate the essential led precisely here to an empty generalization. Even closer rapprochement with ancient art was expressed more in coarsening than in the refinement of the language of forms, since at first only very few workshops of ancient plastics were known. In particular, the relief style of the Roman sarcophagi with their excessive complexity and heaviness became a new then relief style with foreground figures of almost rounded relief.

The important works of Wilhelm Bode and Marcel Raymond perfectly help us to get an idea of the Tuscan plastics of a high renaissance. We owe the work of Burger to a more correct view of the art of the tombstones of this time.

It seems that Giuliano da Sangallo hardly owned the chisel, but in any case he himself created projects for the figured part of his works in the field of applied architecture. Medallions and friezes of frames with arabesques in the taste of the Renaissance on the frames of the niches of the gravestones of Francesco and Nera Sassetti in Santa Trinita in Florence, on which instead of lying figures there are only sharp profiles of the departed, according to their pagan warehouse and language of forms are borrowed from the reliefs of Roman sarcophagi. On the same ground stands the sculptural decoration of his palazzo Gondi (1495) in Florence, while his main altar (1508) in Madonna della Carceri in Prato subordinates Christian traditions to a new understanding of forms.

Giuliano da Sangallo was first a woodcarver and architect, and his successor, Andrea Contucci, nicknamed Sansovino (1460–1529), recently studied by Schönfeld, Maucheri and Burger, was an experienced sculptor from the Pollayolo school. The works of his early Florentine time, in the style of his painted terracotta altar in Santa Ciara in Monte Sansovino, his hometown, are also the works of the last stages of the early Renaissance. What he did during his stay in Portugal (1491–1499) is quite difficult to determine. When, around 1500, he again took up his work in Florence, then immediately beside Michelangelo he represented the new direction. His marble group "The Baptism of the Lord" above the eastern door of Ghiberti in the baptistery in Florence is considered a sculpture of the purest Florentine, high renaissance. Started around 1502, it was completed only decades later by Vincenzo Danti, since the Angel was added in the 18th century. Christ and John the Baptist, whose outstretched right hand with a baptismal cup responds in the sense of contrast with his protruding left leg, belong to the truly classical works of the time. The almost nude figure of the Savior, standing with his hands folded on his chest and his eyes downcast, with such dignified forms, is especially notable for the immediacy of the artistic view. Since each of the two figures is on a special pedestal, this group, of course, is still out of the question. Related to them are the figures of John the Baptist and the Madonna (1503) in the Cathedral of Genoa, beautiful marble statues, still covered with light severity.

In Rome, his seat around 1504, he completed for Julius II both large wall tombstones in the choir of Santa Maria del Popolo, to the left the tomb of Cardinal Ascanio-Maria Sforza in 1505, to the right - the tomb of Girolamo Basso della Rovere in 1507 Both belong to the genus of those Florentine tombstones in the wall niches, which in Rome were framed by the architectonics of these triumphal arches. Their powerful architecture follows the style of the 16th century; in rich ornaments with arabesques, columns, socles and friezes covering them, echoes of quatrocento are heard even. The “virtues” standing in the side niches and sitting higher on the crowning eaves, as well as the statue of Almighty God among the angels, crowning the middle attic, reveal the free and pure language of the forms of the new direction, but are devoid of creative spirit. Marble statues of both princes of the church, dormant under the middle arches on their sarcophagi in semi-erect postures designed for contrasting positions, indicate a transition from the simplicity of the heyday to the intention of a time of decline. Ascanio Sforza, although he sleeps, but supports his head with his right, leaned on his elbow, hand.

Fig. 23. The Tomb of Cardinal Ascanio-Maria Sforza

Andrea's latest works belong to the cathedral in Loreto, where he moved in 1513 and where he continued to live until 1529, when he returned to his hometown on the eve of his death. The task of decorating the niches of the cathedral in Loreto with the figures of kings, prophets and sibyls, like the Casa Santa Bramante, and her large piers with relief images from the life of Mary, required the involvement of numerous employees, from whom Tuscans should be called Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, who was called the name of Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, named after, Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, named after, Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, called by the people of Tuscany, Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, nicknamed by Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, called the Tuscans, Francesco Sangallo, Raffaello da Montelupo and Niccolo Pericoli, called the Tuscan people. . Among the most beautiful, although somewhat overloaded, conceived in this picturesque relief style, belongs the Annunciation, in which the Virgin Mary almost involuntarily turns to the angel, and God the Father rushes over him among heavenly forces in a movement that quite clearly resembles the Almighty in the plafond Michelangelo. In addition to this relief, Andrea himself also performed the relief of the worship of the shepherds, and in the performance of others, apparently, only participated. The figures of the prophets and the Sibyls in the niches also reflect the strong influence of the paintings of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel already described, before which neither friends nor enemies could resist.

2. Works by Benedetto Rovezzano

Peer Rustichi Benedetto Rovezzano (about 1474–1554), despite the imperfection of his figure works, such as the monotonous reliefs of the gravestone of St.. Gualbert at the National Museum in Florence, is still a bold innovator in the field of ornament. He treats old motives with greater force and, at the same time, sharper chiaroscuro than his predecessors; Skulls and weapons serve as new motives for it, for example, on the sarcophagus of Oddo Altoviti in the Church of the Apostles in Florence. Finally, the Florentine Lorenzetto (died in 1541), who should be looked upon as a disciple of Raphael, gained more fame by performing pure shapes of Raphael to the marble Jonah, emerging from the belly of the whale, and to the bronze relief of the Conversations of Christ with a Samaritan Woman in a Chapel Chigi in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome than his own weaker works.

Fig. 24. Relief of the Conversation of Christ

Andrea Sansovino’s real student was Florentine Jacopo Tatti (1486–1570), named after the master Jacopo Sansovino. Settling in 1527 in Venice, he quickly

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)