1. Painting of France of the XVI century

The French painting of this time in essence was also decorative art. The overall impression was not given by individual easel paintings, but by extensive, with stucco works, ceiling lamps and murals of the Italians Fontainebleau drafted to France, local works of French painting on glass, more suited to the spirit of the times than to style, and finally a series of artistic woven carpets, more more luxuriant than before, although inferior to the Belgian, and art-rich small works of new Limoges enamel. The art of reproduction also flourished in France, but woodcut and copper engraving did not rise here, however, to such an independent meaning as in Germany and the Netherlands.

We have seen how the French easel painting of the transitional period from the 15th to the 16th century developed on a national basis, wider and fresher than it had been accepted until recently, in the hands of such masters as Jean Bourdichon and Jean Perreal, who created, in addition to numerous architectural and sculptural projects, maybe such significant paintings as the altar peninsula in Moulins. From this, however, it cannot be concluded that French easel painting at the height of the 16th century took a place equal to Italian, Dutch or German painting. As we shall see, the founders of the new French portraiture were again the Dutch, and the only master of church easel painting, Jean Belgamba from Douai (between 1470–1534), thoroughly studied by Degenes, can be as easily attributed to the Netherlands as it is to the French. In essence, the Belgambus adjoins, on the one hand, Memling and David, and on the other hand, it reminds both Bourdison and the master of Moulins. His slender figures, delicate faces, elegant individual forms, in any case, are more French than Dutch. Some of his altars, such as, for example, in Notre Dame in Douai and the altar of the Lille Museum with the mystical bathing of souls in the blood of the Savior, are distinguished by original theological tasks, others, such as the Last Judgment in the Berlin Museum and the two altar folds of the Cathedral of Arras, are independent the plan of ordinary plots.

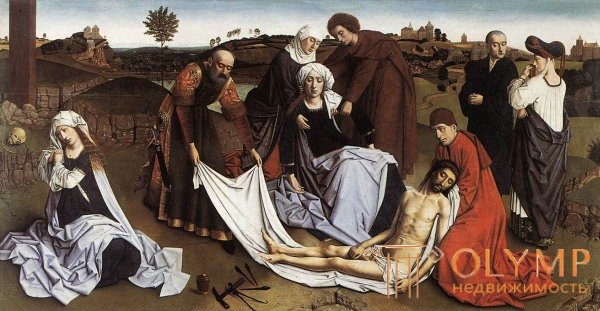

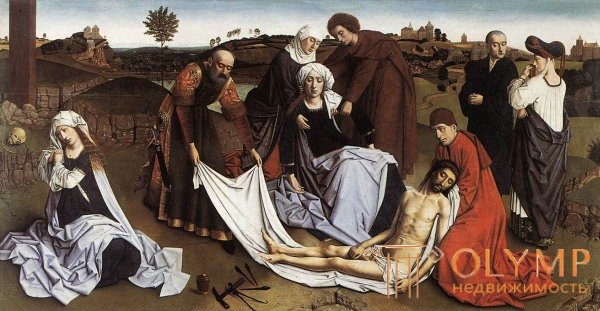

The first major Italian painters of the 16th century, who arrived in France, for example, Andrea Solario, who painted the Chapel in Galion in 1508, Leonardo da Vinci, who was drafted to France in 1516 by Francis I and died here in 1519, Andrea del Sarto, arrived in 1518 and the following year, who returned to Italy, did not have a special influence on the development of French painting. The masters who called up from Italy to Fontainebleau by Francis I immediately had a greater influence immediately after the death of Perrfal, where it was necessary to decorate a new palace. In 1530, the Florentine follower of Michelangelo, Giovanni Baptista Rossi (1494–1541), nicknamed Rosso Fiorentino or Maitre Roux, arrived; it was followed in 1531 by the Bolognese Francesco Primaticchio (1504–1574), who, under the leadership of Giulio Romano in Mantua, developed into a sculptor of knock ornaments and a decorative painter; Rosso and Primatichio (“Le Primatice”, to which Dimier devoted detailed work) are the two pillars of the school of Fontainebleau, which, based on the decorative principle, plunged French art into the style of Mannerism earlier and more decisively than it did in Italy, where this style took over painting only in the second half of the XVI century. Niccolo Abati, nicknamed Dell Abate, from Modems (1512–1571), the third member of this union, who developed alongside Correggio and Giulio Romano, came here only in 1552. Of the large stucco reliefs and paintings that these masters and their weaker students decorated the walls and ceilings of the hall and rooms, stairs and galleries in Fontainebleau, relatively few survived. But the lists of pictures already published by Dimie allow us to see that here it was a matter of subjects from ancient mythology and poetry. In the "Gallery of Francis I," preserved, albeit rewritten, twelve large paintings of Rosso with events from the king's life and mythological paintings. They differ in their more perfect and coarser language of forms from the works of Rosso's followers, whose distinctive, cold and hard manner is most clearly already in his highly pathetic "Crying over the Body of Christ" in the Louvre. Of the earliest works of Primatichio in Fontainebleau, for example, in The Room of the King (1533–1535), almost nothing is preserved: his famous Ulysses gallery with numerous paintings from the Odyssey reached us only in engravings by van Tulden. The best of his works and the most important one in Fontainebleau has long been considered to be the decoration of the walls and the ceiling of the Henry II Gallery, which served as a ballroom, in many respects by the hands of students. About this work many years ago I wrote this: “There we see Parnassus and Olympus; there we welcome Bacchus and his retinue; there we are present at the magnificent wedding of Peleus and Thetis; there we look into the dark forge of Vulcan and into the shining palace of the sun god. ” “A harsh mannerism, developed from Primitichio’s desire for a coquettish grace, his terrible manner of writing every figure belonging to groups of nude bodies. a special, arbitrarily taken bodily tone, flowing into red, then white, then purple, and no less unpleasant attachment to overly elongated forms with incredibly long hips and intentional angles "are too characteristic of the manner of this period, to whose fathers Primatichio. Finally, Niccolò del Abate is, in Fontainebleau, in essential terms, only one of the accomplices who perform the Primaticcio; at least Abate's hand can be found in the pictures from the life of Alexander of the present staircase.

Fig. 90. "Crying over the Body of Christ"

Fig. 91. "The Last Judgment" in the Louvre

French masters of this kind gave really the best works in compositions for painting on glass and for woven works. Painting on glass experienced in France in the first half of the XVI century its second, large, brilliant flourishing, explored in particular by Manim. It goes without saying that in France, as elsewhere, the former art of drawing pictures from colored glass, resembling a mosaic, has now gradually become the art of painting on glass. The perfect enamel painting on glass, which was despised by Angerran le Pence (d. In 1530), was, however, switched only in half a century; At the same time, old original compositions in some places, such as, for example, in the church in Konshe, began to give way to imitation of German and Italian engravings on copper, until the Fontainebleau school even came up with its own works here. The windows of the church in Montmorency (1524) are considered the most beautiful and interesting in terms of the first, still quite strict half of the 16th century, the master of which should be considered Robert Pinegrier, author of the great Court of Solomon (1536) in Saint-Gervais in Paris, now cut by a window jamb. Saint Godard in Rouen, Saint Etienne in Beauvais and Saint Madeleine in Troyes possess picturesque windows of the best time of the XVI century. To the transitional time belong the windows of the church in Montmorency and the windows (1544) in the rural church in Ecuane, with the Annunciation in a room decorated in the spirit of that time, on one of them. In these windows, the former yellow silver of large architectural paintings of the 15th century is replaced by cold, light colors, which were promoted by Guillaume de Marsill, a French glass painter, using them in his Italian series of windows, for example, in the windows of the cathedral in Arezzo, where he died in 1537 Mr. Jean Cousin is attributed to the windows of the life of St.. Eutropia (1530) in the richly painted windows of the Cathedral in Sens, without firm confidence some of the many painted windows in Saint-Etienne-du-Mont and Saint-Gervais in Paris, and with full right five windows with images from Revelation of St. John in the palace chapel in Vincennes. The Italian influence, not yet noticeable in Montmorency and classically rigorous in Ecuane, reached here its full manifestation in the spirit of the Fontainebleau school.

Woven carpets for the castle walls were the same as painting on glass for churches. This art moved from the 15th century from Paris to Arras, and from Arras to Brussels, and therefore the French kings of the 16th century tried to save it for France as much as possible. Francis I founded a carpet factory in Fontainebleau around 1535, and Henry II added the Trinite factory in Paris to it. The works of the factory in Fontainebleau are mainly considered to be wall carpets decorated with grotesques, and in the middle are enclosing cartouches with mythological scenes. Of these, two are in the Tapestry Museum in Paris, and the other two are in the weaving museum in Lyon. Dimieu attributes their compositions to Primatichio. The works of the Trinite factory are carpets with the history of the Mausoleum and Artemisia at the National Furniture Storehouse in Paris.

2. Enamel painting

In close contact with the transformation of painting on glass, the further development of Limoges enamel painting, which we described earlier, was accomplished. In its new form, namely in the form of painting with a grizzly (gray over gray) with reddish-purple bodily tones and golden hatching against a dark background, it prevailed in the XVI century and became widespread precisely because it began to serve to decorate ordinary vessels. The enamel of the oval shield (1555) in the Louvre can serve as a brilliant example of the rich color, sometimes encountered in gray tones next to the dominant painting. The images of most Limoges vessels kept in gray tones are still often borrowed either from German or Italian engravings on copper; however, there is no shortage of portraits, which usually occupy a place in the middle of the vessels. Small triptychs with venerated images join the vessels, and portrait works are independent works of this national-French technique. In a number of enamel artists, Léonard Limousin (1505–1577) stands out, starting with 18 bowls in one of the Passion of Dürer series (1532), then performing a series on the frescoes of Raphael in Farnesine (1535), but reaching its full strength in twelve large boards with images of the apostles in the church an. Peter in Chartres (1545), which are based on the colorful sketches of the painter Michel Rochelle. The most famous, however, are his portraits on blue backgrounds, in black, white, and gray with a slight increase in yellow and brown, and only slightly touched on his cheeks pink; thanks to their blue eyes, they give the impression of writing blue on blue. His best portraits of this style belong to the Cluny Museum and the Louvre in Paris.

3. Portraitists

After Clouet, the most beloved portrait painter of France in the middle of the century was the Dutchman Corneille de Lyon, Corneille de la Gaye proper. Its styling is even more subtle than that of Francois Clouet; his painting with a preference for light green backgrounds is light and light, and his faces are captured and transmitted lively, sometimes without afoot, naturally. Portraits of Francois - the Duke of Angouleme, and Marguerite de Valois in Chantilly, then the second portrait of this princess and the portrait of Jacqueline de Rogan in Versailles - the best of his work. Paris exhibition in 1904 added to the paintings of Francois Clouet and Corneille de Lyon a number of new ones.

Further names extracted from archives do not give anything new. We cannot dwell either on masters like Toussaint Dubreuil (died in 1602) and Jacob Byunel (died in 1614), as Ambroise Dubois (died in 1614) and the celebrated Marten Fremine (1567– 1619), these epigones of the school of Fontainebleau, judging by their paintings in the Louvre. Lyonian painters, examined by Rondo, and masters of Provence, studied by Gonico, have to be left for the history of local arts.

School of typography and wood engraving flourished in Lyon. Next to her engraver on copper Claude Corneille is less valuable, precisely because it resembles the German small masters. Significant was Jean Duvé of Langres (born in 1485), leaning now towards Dürer, now towards the Italians, but still showing a rich and independent imagination on his 24 sheets of the Apocalypse. The best French engraver of the XVI century was Etienne Delon (1519–1595), the author of about 400 sheets of engravings of the most diverse content, made half-dotted and strokes. Under the leadership of the school of Fontainebleau, the French engraving then proceeded to spread the works of other masters and to imitate the Italian mannerists, their calculated, fake style. Only the 17th century brought new and independent growth to French painting.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)