1. The formation of German sculpture

About the great German transition sculptors from the 15th century to the 16th century, Feit Stösse, Adam Kraft, Peter Fischer and Tilmane Rimenshneider, who gave eternal expression to their independent sense of nature and style in the wonderful works of wood, stone and bronze, we already mentioned in the second volume, in accordance with the time of their life and their late Gothic direction. After them in Germany there were neither major masters nor large orders for large sculptural works. The struggle of religions in this area acted in a destructive way. Life-size statues were put, speaking briefly, almost exclusively on tombstones, arising hundreds, but artisan. The same can be said about altars, decorative reliefs and carved panels. Prominent masters we find mainly in the field of small plastics. We owe the old information on the history of German plastics in the Renaissance style to Neiderfer and Hochstetten, and to Lyubka and Bode her best descriptions.

At its head are sculptural decorations (1510–1512) of the Fugger Chapel in the church of Sts. Anne in Augsburg. Robert Fisher showed that the cardboards for the two large reliefs, “The Beatings of the Philistines” and “The Resurrection of the Dead”, with figures of deceased Fugger resting on their pedestals, were painted by none other than Durer. Usually, their sculptor was considered the sculptor Adolf Dauher (or Dower), born in 1460 in Ulm and died in 1523 or 1524, while Otto Wigand did not speak out against this, and then Felix Mader, who apparently correctly attributed their performance to Loy Göring Religiously belong to Adolf Dauher and his son Hans-Adolf strongly, sharply and confidently cut in the tree half-figures of the Old Testament persons with features of Fugger, on the seats of the choir of their choir. Now fifteen of them belong to the Berlin Emperor Friedrich Museum, and one adorns the Figdoro meeting in Vienna. The authentic work of Adolf Dauher is also a stone, Renaissance altar (1518–1522) with the ancestors of Christ in the city church in Annaberg.

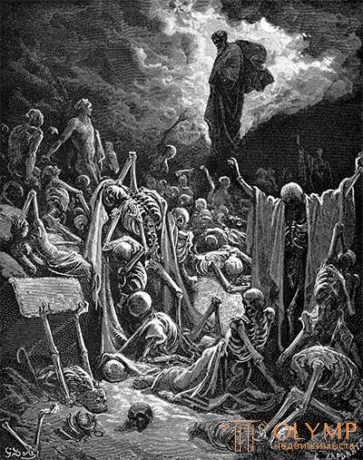

Fig. 60. "The Beatings of the Philistines."

Fig. 61. Resurrection of the Dead.

The main work of the German Renaissance sculpture after the tomb of St.. Sebald by Fischer - is a monument to Emperor Maximilian in the court church in Innsbruck, the story of which was detailed by Schöngerr. The original project belonged to Conrad Pevtinger, scientific secretary of the city of Augsburg. Around the sarcophagus, decorated with 24 reliefs from the life of Maximilian with a kneeling bronze figure of the emperor on his lid and seated, bronze, very lively statues of virtues, the corners stand on four sides 28 (instead of the planned 40) bronze statues of life-size ancestors of the emperor, of which Two of the most beautiful belong to the workshop of Peter Fisher. The rest, performed by painters, Gilgom Sesselshreiber, Christoph Amberger and Jörg Kolderer (died in 1540) and cast by casters like Stephen Godl (mind in 1534) and Peter and Gregor Löfflers, of unequal dignity. Figures Sesselshreiber rough and dry in shape, are distinguished by diligent transfer of parts of clothing and weapons. The most purely shaped figures of the Archduke Sigismund (1523) and Empress Maria Blanca (1525) are drawn by Coldrerom and cast by Godel. In 1561, three Abel brothers from Cologne were invited to make a marble sarcophagus. Florian Abel (died in 1565), court painter in Prague, made a sketch of dramatically conceived reliefs, and Bernhard Abel (died in 1563) and Arnold Abel (died in 1564) took upon themselves the execution in marble , but did not bring it to the end, but were transferred in 1562 to Alexander Colin from Mecheln, who completed it, technically superb, but in a simplified language of forms. Then Colin fashioned four virtues in the corners, cast in 1570 by Hans Lendenstreich from Munich, and a magnificent, extremely lively figure of the praying emperor, the casting of which was performed in 1582–1584. Italian Ludovico de Duca.

Of the rest of the Augsburg sculptors of the first half of this century, the sons of Adolf Dauher, mentioned already by Hans-Adolf and Hans, apparently had more inclinations of independent creativity than their father. Hans Daucher, whom Bode and Gabih wrote about, is an excellent master with a clear form language in his stone reliefs, for example, in the Paris Court of Ambrasov Assembly in Vienna, the comic contest between Durer and Spengler in the Berlin Museum, the epitaph of Knight Funk-Gerwart in the church of St. Magdalene in Augsburg and in the statue of Emperor Maximilian as St. George collection Lanna in Prague. Loy Goering (died about 1554), whose tombstone for the grave of Eltz in the parish church in Boppart borrows its relief from the Durer engraving depicting the Trinity, was a student of the deceased as early as 1508 or 1509 of Hans Beyrlin (Beyerlein). His monument to Zollern in the cathedral in Augsburg, as we have seen, shone with the light of a new time. The tombstones of Goering in the cathedrals of Bamberg, Würzburg, Eichstett and his altars in Eichstätt and other places are decorated with reliefs mostly from drawings by other artists, but the portraits on them are made by him alone, and the ornament is transmitted in a directly adopted Upper Italian Renaissance style.

When then at the end of the century it was necessary to decorate Augsburg with fountains, they invited, as is quite characteristic, the Dutch masters. Hubert Gergard of Herzogenbusch performed in 1589–1594. under the different influences the fountains of Augustus in the spirit of Giovanni da Bologna, Adrian de Vries from The Hague (about 1560–1627), whom we will meet again, finished the fountain of Mercury in 1599, and in 1602 the luxurious fountain of Hercules, with his simple forms of naiads. The bronze figures of these fountains were cast in Augsburg. Technique was kept here longer than art.

2. Dürer and sculptures

In Nuremberg artistic life, beginning in 1500, along with the aforementioned senior great sculptors, dominated the noble, stately personality of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Whether Dürer also engaged in sculpture, this controversial issue is now resolved in such a way that the famous Galim described last time, famous for the frequent repetitions of the relief of a standing nude female figure with his back to the viewer, whose original is in stone in South The Kensington Museum in London, followed by three medals with male portraits and a female head. In an excellent, beech-carved nude female figure, privately owned in Berlin, Friedländer even thinks of seeing Dürer's handwriting. We will, however, become more solid if we return to the workshop of Peter Fisher. Three large bronze tombstones, performed by his sons Peter Fisher, Jr. (1487–1528) and Hans Fisher (from 1488. and after 1549), we already know. One should add the already completely flat gravestone of Bishop Sigismund belonging to Hans Fischer in the cathedral in Merseburg (1540). The small bronze sculptures of both brothers belong to the best works of the German Renaissance. The four plates of Peter Fisher, Jr., depicting Orpheus and Eurydice, are full of inner life. Three of them belonging to the Berlin Museum, the Hamburg Art Gallery and the monastery of St.. Paul in Carinthia, depicts Eurydice when she prepares to follow her lagging spouse, and the fourth, in the Dreyfus collection in Paris, represents her already ready to return to Hades. In a round bronze casting, two well-known ink tanks with the image of a naked woman follow in symbolic contrast with the skull at her feet, one at Mr. Fortum in Stanmore, the other at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The hand of Peter Fisher Jr. then belongs to three medals, of which one is from 1507 with the image of Herman Fisher, his early deceased brother, the oldest of all German medals.

The symbolic drawing of his work in the Goethe Museum in Weimar is the earliest work of art of the Reformation. Finally, Seeger ascribes to Peter Fisher the youngest yet exquisite wooden statue of Madonna, standing with folded hands and looking thoughtfully up to the sky in the German Museum, representing in any case the finest work of Renaissance sculpture of the Nuremberg heyday. Hans Fischer is also a sophisticated master of small bronzes, such as the small Apollo Archer (1534) of the Town Hall courtyard (now in the German Museum), inspired by Barbury’s engraving, which is represented by the nude youth of the Munich National Museum.

Peter Flettner, who lived in Nuremberg around 1522, diversified and traveled a lot in 1546, was not a natural Nuremberg, but according to Gaupt’s suggestion, he was rather a Swiss from Lake Constance. A small statue of Adam of beech wood with his signature in the artistic and historical court museum in Vienna was designed to be sharply realistic. His numerous lead and bronze plates with mythological and symbolic images, remarkable for their landscapes, mostly as originals, were intended for jewelry works, and not less numerous medals with sharply vital profile portraits show in him a versatile renaissance sculptor. The names of Goltschuera in Augsburg belong to his silver-trimmed glass of coconut, the stem of which represents the grapevine with cheerful groups, the belly of the bacchus scenes, and the lid of the life of the miners. If, from the time of Neudeferfer, the most exquisite master of German jewelry was considered the exalted crown of Wenzel Jamnitser (1508–1588), then Lange believes that Benletuto Cellini should be considered the German Flettner. Yet the elegant Yamnitsera cutlery from 1549, owned by the Rothschilds in Frankfurt, is the best piece of Nuremberg jewelry. The luxurious vessels of the Lüneburg treasury at the Berlin Museum of Industrial Art give an idea of all the disadvantages and merits of German jewelry art, which worked mainly on engraved, painted or carved originals of painters and plate makers.

Over the silver altar of the Krakow Cathedral, richly decorated with reliefs, Nuremberg Pankratiy Labenwolf worked next to Flettner, who in his famous bronze Man with Geese on the Nuremberg Fountain (1557) directly designed the work of real folk art; while the “Fountain of the Virtues” by Benedict Wurzelbauer (1589), whose water flows from the breasts of the female figures of the “Virtues”, gives the impression of already deliberate disenchantment.

The best sculptor, who appeared in the first half of the XVI century in the Rhineland, was Conrad Mayt of Worms, whose activities outlined Baud, and more recently Feuge. The alabaster statuette of the naked Judith in the Munich National Museum with his signature represents the complete, very truthfully made figure of a woman with tied braids. Similar to her are boldly made of beech wood statues of Adam and Eve in the Gothic Museum and in the Imperial Museum in Vienna, as well as a number of excellent busts, of which the extremely lively bust of a young man in the Museum of the Emperor Frederick is worth noting. The best great works of Mate, which are abroad, are the gravestone sculptures of the Duke Philibert of Savoy and his wife Margaret of Austria in the church of Sts. Nicholas Tolentinsky in Brut in France (1526–1532), in two forms, in the form of the dead and living. This also includes the recumbent image of Margaret Bourbon, the mother of the duke, and the charming, full of life winged boys playing around the recumbent images in the form of living people. Mayt is not responsible for the general plan, nor for the Gothic architecture of these monuments, but the five lying images, executed in part in alabaster, part in marble, are made extremely fresh and subtle; The already mentioned charming “putts” are, according to Feug, its distinguishing feature. In general, German art has not created anything more tender, more fresh and more Italian than these winged boys.

3. Nizhnereinsky school

In the second half of the century, however, near the already mentioned brothers Abel of Cologne, who performed the tombstones of Otto-Heinrich and Philippe of Palatinate, unfortunately destroyed by the French, we find the work of the already mentioned Dutchman Alexander Colin, who performed most of the very 15 shallow by the idea of sculptural decoration of the Otto-Heinrich building and then moved to Austria, where after finishing work on the Maximilian monument in Innsbruck he performed excellent, though not particularly deep in impression, tombstones e monuments of the emperors in the Prague Cathedral (1564–1589) and statues adorning the monuments of the Philippines Welsers and her husband in the court church in Innsbruck (1580–1596).

The further development of the Nizhnereinsky school of sculptors in Kalkar in the person of Heinrich Douverman, first mentioned in 1510, his son John Doverman and their pupil Arnold Tricht, last mentioned in 1561, was introduced by Beissel. It was in 1510 and 1561. in the sculptural works of these masters in Kleve, Kalkar and Xanten the transition from the late Gothic to the Renaissance was accomplished.

In Saxony, the already mentioned Dauhera altar in 1522 in the town church in Annaberg stands at the beginning of the sculptural renaissance. The hundred reliefs of biblical and symbolic content on the railing of the same church, performed by Theophil Ehrenfried with their students, are still quite late Gothic in nature. Here we cannot trace further the Upper Saxon wooden carved altars, mostly belonging only to the 16th century, especially since the study of their development undertaken by Flexig is not yet completed. Only one Lower Saxon master, Hans Brüggemann of Walsrode, who probably grew up on Dutch carved altars with small figures, which then flooded northern Germany, stands out as a strong artistic person. Michelsen and Döbner closer acquainted us with him. His main work is a large carved altar (1515–1521) in the cathedral in Schleswig with unpainted images of the Passion of the Lord in curly late gothic frames, which is not so much the purity of the forms of individual figures and the completeness of the groups as the transmission of the life drama of the events depicted.

Fig. 62. Church of sv. Sebald in Nuremberg

Stone plastic in both upper and lower Saxony already in the second half of the 16th century fell under the influence of Italianized Dutch art. It shows the beautiful, rich in figures tombstone of the Elector Moritz in the cathedral in Freiburg (1588–1594), on which various Dutch artists worked; This is also evidenced by the tombstones of the Friesland duke Enno II in the main church in Emden, Archbishop Adolf von Schauenberg (after 1556) and his brother in Cologne Cathedral, king of the Danish Frederick I in the Cathedral in Schleswig (1555), the work of the famous Antwerp Cornelis Floris and a more superficial and mannered in appearance tombstone of the Friesland duke Edo Wimken (1561–1564) in the church in Iever. The intensely elongated look, taken by the departed, lying on beautiful sarcophagi, often carried by caryatids, is reminiscent of Dutch art everywhere. Gendke discovered that in Silesia a similar development of stone gravestone sculpture entered the Dutch current.

Truly German sculptural works throughout the XVI century remained mentioned works of small art, between which play the role of a medal, such as Hans Schwartz and Friedrich Gagenauer, investigated by Hermann. The more German taste at the end of the century, the more majestic, the more it demanded brilliant and pure forms, the wider the gates opened to meet foreigners and foreigners.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)