1. The birth of Baroque in Italy of the XVII century

In the 17th century, the Baroque style dominated the architecture of Italy, distinguished at an early stage of its development by severity and simplicity, but over time leaning toward pomp and elegance of forms. The first representatives of this style were the architects who worked at the very beginning of the century.

The contrast between the pompous vanity and natural simplicity, everywhere appearing in the art of the XVII century, mainly in local forms, reflects the struggle of the higher spiritual forces, which has engulfed the whole century. She raised her head more than ever, the church, passionate and loving the pomp, but also a new gospel confession, tempered by a bloody struggle, even deeper than before, rooted in those countries that turned to it. And if on the threshold of the century (1600) the great thinker Giordano Bruno was still burning, then in the second half of this period (1673) the creator of a pantheistic world view, Boruch Spinoza, was already honored by the invitation, but to no avail, to the University of Heidelberg. It is in the plastic arts that this opposite of directions is clearly seen everywhere. Along with the omnipotent movement of the Baroque, a barely less powerful naturalistic trend, often mixed with the first, appears in all areas of art. But, needless to say, the Baroque style, with its movement of the masses, its outward passion, its translation of the usual language of forms into forms of intoxicating luxury, flourished mainly in the countries of the old faith, which helped her to achieve an unheard of, often quite superficial brilliance, therefore , mainly in Italy itself, and the return to nature was most decisively realized in the countries that sought state and church freedom, that is, mainly in Holland.

It was in Italian architecture that the real Baroque style flourished during the 17th century, whose development from the 16th century Roman Renaissance, as well as the first major steps in the works of Michelangelo, Vignola, Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana, we already traced. External grandeur, passionate, contrasted movement and the desire to fascinating impressions of Italian architecture - the same in Italian painting and sculpture. Which of the three arts first entered upon this path is not easy to say. At first glance, it seems as if architecture was moving ahead, whose mobile, often fake massiveness in many individual cases caused the development of similar features in altar images, ceiling painting and plastic works intended for an impression from afar in these magnificent buildings. Continuing to honor in Michelangelo a true “father of baroque”, we recognize nevertheless that the Baroque style arose primarily from the inner desire of time to impart to the human body in the visual arts a greater and more impressive, more and more deliberate movement. In reality, the same passage of time, led by great masters, simultaneously guides all three arts in the same way.

In Rome, the real homeland of the Baroque, grandiose, noble, strict early Baroque, which follows the XVII century, in the further development gradually gives place to more joyful and easy forms. The Wolfflin considers it to be the border of 1630. Columns and pilasters around this time again begin to be replaced by columns that first appear on the facades, projecting only half or a quarter of the wall, but then quickly and freely seize the interior. The majestic unity of the building, giving it plasticity, gives way to picturesque divisions of space with promising gaps and cuts. Powerful, simple facades of palaces again acquire a richer decorative dismemberment. Even the church central building, which in the early Baroque gave way to a completely rectangular or oval oblong building, is being revived again. But only now, after shy earlier attempts, the vertical walls, bent inward and outward, also acquire the mobility of forms, and the love of pomp is already connected here in places with playful charm preparing the rococo style.

Creativity Carlo Madern, and his followers

Lombardian Carlo Maderna (1556–1629), nephew and pupil of Domenico Fontana, a follower of Giacomo della Porta, the first powerfully and vitally introduces the early Baroque of his predecessors to the environment of more fussy pomp of the XVII century. Comparison of its facade in 1603 of the Church of Sts. Susanna in Rome with the front of the Church of Jesus Port, whose daughter is the first, quite clearly reveals further development. In the church of sv. Susanna stronger stand out the outstanding parts. In the lower tier, the pilasters are already replaced by added round columns. At the top - the niches between the pilasters are crowned with torn gables. The slopes of the main pediment are sharply highlighted by means of a goalless balustrade. Maderna is especially famous for its completion of the longitudinal corps of the church of Sts. Peter, to whom he attached a magnificent courtyard with a wide-spread restless facial facade, designed primarily for the cubic corner towers, topped with domes on the lanterns. The main forms of Michelangelo, namely the grandeur of the Corinthian order inside and outside and the four-column middle gallery of the facade, topped with a pediment, Maderna retained. But he also placed these protruding columns into deep depressions, turned the open colonnade into a magnificent closed vestibule, and thus the restlessly expressed life of the whole front side, in comparison with which the movement of Michelangelo seems to be a state of peace, makes it possible to recognize the pulse of a new time.

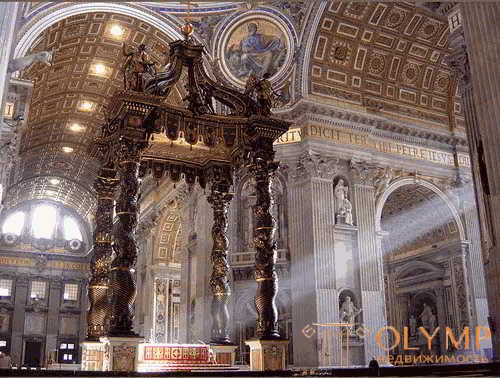

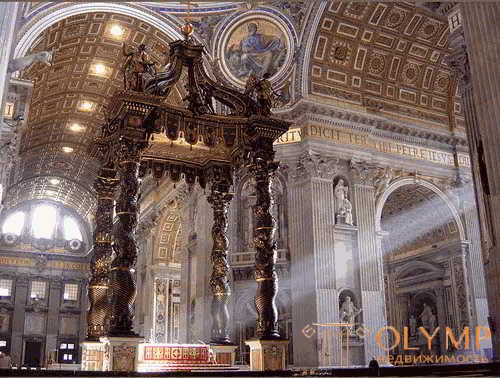

Fig. 98. Bernini. Colonnades of the Cathedral of Sts. Peter in Rome.

Fig. 99. Senj in the cathedral of st. Peter in Rome by Lorenzo Bernini

2. Baroque in Rome and Florence

In Rome and Florence, the main centers of classical Italian architecture, there is the greatest variety of Baroque styles and forms. The main examples of art of the era are the numerous palaces and churches of these cities.

If Bernini rarely falls into exaggeration or lewdness in separate architectonic forms, then his contemporary, the Lombardor Francesco Borromini (1599–1667), is mainly responsible for the victory of the curving lines inside and outside the facade and the picturesque play of light and shadows on the outside. buildings with strongly protruding and protruding parts. The curving inside of the Tsekka-vecchia Antonio da Sangallo was only an easy first beginning. Borromini's small church, San Carlo Alla Quattro Fontane in Rome (1640–1667) is the first church building, built entirely on the basis of pictorial irregularity and curved main lines. The amazing fullness of life grows here in the close construction of the building. If it is impossible to deny the ancient origins of individual forms, then the general impression has already been abandoned of any connection with classical antiquity. Borromini returned to the central building of Sant'Ivo, Alla Sapienza, whose main walls are curved to the outside, and the walls of the domed drums inward. Of the rest of his church buildings, the oratorio San Filippo Neri in Rome is remarkable for its slightly curved inward facade, its pediment, giving the impression of an almost late Gothic, and fancy extensions over windows and capitals of pilasters; "College di propaganda fide", begun by Bernini (1660), is replete with all sorts of protrusions that could fit on a narrow street facade. From the secular buildings of Borromini, the court side of his Palazzo Falconieri in Rome reveals the whole powerless arbitrariness of the master, and the second courtyard of the Palazzo Spada tends to create an illusion of depth, which does not possess, through a passage with perspectively made relief images.

The name Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669) is closely connected with the majestic baroque ceilings, composed of gilded, intersecting and intertwining stucco frames and luxurious, figured and ornamental painting, in large palace halls of the middle of the XVII century. The most famous are its ceilings in Palazzo Barberini in Rome and Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Domestic church decorations, as in Chiesa Nuova and San Carlo al Corso in Rome, abut here. Everything is solemn, luxurious and colorful. His own buildings are less baroque in detail than they are in general impression. How delightful inside the domed church of st. Luke and Martin in Rome, twelve pairs of Ionic double columns, four of which, with the corner pillars of the medium cross, support the dome arches, while the rest guard the altars in absties at the ends of the elongated branches of the cross. How interesting is the exterior of Santa Maria della Pace in Rome with its prominent and protruding parts of the walls, again giving the impression of being more extensive than in fact, thanks to the tricks of perspective! Carlo Rainaldi (1611–1691) went even further than his predecessors in using strongly protruding and extending facades to revive them with the play of light and shadow. The luxurious strong and clear impression makes Sant'Aniese on Piazza Navona (1652), a spacious church with towers, created with the participation of Borromini. Santa Maria ai Campitelli (1665) with its powerful belts of protrusions, with Corinthian columns free-standing at the walls, too far-out projections of cornices and whimsical cutouts of the pediment, seems unbridled and perky. How classically calm the face of the Church of Jesus, belonging to della Porta, seems to be compared to it! What a development fraught between this building and this has happened! However, the scattered facades of San Marcello and Santa Trinita Carlo Fontana (1634–1714) in Rome represent such bad taste, which could only be caused by the deliberate mixing of Bernini and Borromini styles. Having transferred both styles beyond the Alps at the beginning of the 18th century, Fontana contributed a lot to the further spread of the external design of the Baroque Italian style.

Florentine Baroque School and its merger with the Roman

Surviving the described organic development in Rome, the baroque architecture in Florence, without fussing, embarked on more serious paths in the Buontalenti school. The painter Ludoviko Cardi, nicknamed Cigoli (1559 to 1613), executed here a still calm palace facade, like his wing facade in the Ranuccini Palace, with a portal and windows framed in the lower floor, while its later Palazzo Madama in Rome though neglects the dismemberment of the facade through pilasters, but gives the impression of the full force of high baroque heavy ledges of consoles, ledges above the windows, a balcony crowning the portal with columns and a frieze randomly dissected by mezzanine windows under a powerful coronal eaves. On the contrary, in his luxurious princely chapel of San Lorenzo (1604), Mattei Nighetti (died in 1619) gave one of those solemn secular halls in which the poverty of the architect’s thoughts was completely obscured by the magnificence of the building material.

Fig. 100. Pietro Gvarini. Palazzo Carignani in Turin

The merger of the late Florentine and Roman schools took place, if Gurlitt is not mistaken, thanks to Carlo Fontana, to whom he attributes the Baroque style. Барочную фантазию Гварини превзошел лишь иезуитский патер Андреа даль Поццо из Триента (1642–1709), который, исходя из живописи с перспективной архитектоникой, расширяющей пространство, перешел к пластической архитектонике алтарных сооружений и кончил остроумными, правда, не осуществленными в Италии, проектами целых зданий. В специальной книге защищал он свои необузданные фантазии об античных колоннах. Прославилась его защита «сидячих колонн» на одном из его алтарных набросков. Всего лучше можно ознакомиться с ним в церкви Сант'Игнацио в Риме. Коробовый свод нефа превращен фресковой живописью Поццо в высокий открытый двор, на который смотрит небо с его святыми. Его фрески в куполе и алтарных нишах также сводят небесную бесконечность в земное пространство, которое с легкостью удваивается, утраивается, удесятеряется. Из его алтарей, однако, наиболее известен алтарь Луиджи Гонзага в Сант'Игнацио и иезуита Лойолы в церкви Иисуса.

3. Architecture of Upper Italian cities

The architecture of Venice, Genoa and other cities of Upper Italy has its own characteristics in this era. Baroque also dominates the construction of palaces and churches, but their styles are significantly different from the Roman ones.

Along with all this, now expanding, then waning splendor, the architecture of both Upper Italian rulers of the sea, Venice and Genoa, went in special ways.

Venice Architecture

Fig. 101. The Church of Santa Maria della Salute designed by Longen.

His younger rival Giuseppe Sardi or Salvi (about 1630–1699) joined Longon, supplying in 1689 the church of Santa Maria degli Scalzi, conceived by Palladio, with its luxurious two-storeyed front facade consisting of wall columns, Corinthian double columns and socles, decorated in the manner of carpentry work. But the highest point of exaggeration was achieved by this style in the front of the Moses Church (1648) Alessandro Treminian (Tremillione), where the columns of the lower floor, according to Delorm, flaunt their rustic furniture, and the pilasters of the upper floor are interrupted by a powerful semicircle, whose door trim is decorated with sarcophagi Lush rimmed moldings cover all architectural forms.

The secular buildings of the followers of Longen soon became more schematic and dry. However, the customs of Giuseppe Benoni (Dogana, 1678–1681), a triangular and rustic arcade with a baroque tower, deserves mention already by the courage with which it settled at the foot of the Salute church in front of the Canal Grande.

Genoa architecture

Fig. 102. The courtyard of the University of Genoa designed by Bartolommeo Bianco

That Genoa and in church architecture almost alone in all of Italy remained true to the columns, we have already seen. In the middle of the 17th century, it also returned to the central building, as shown by the churches of Sant'Antonio Abate and Santa Maria di Rimedio.

The more significant Upper Italian central churches of this century are Sant'Alessandro in Milan Lorenzo Binago (1602), whose later appearance in the style of high baroque does not harm the stately interior, and the new cathedral in Brescia Giovanni Lantana (from 1604) is one of the cleanest and the noblest buildings of this century. Palazzo di Brera in Milan, made in 1651 according to the plans of Francesco Maria Ricchini, belongs to the most luxurious Upper Italian palace buildings of this era. His courtyard, surrounded by arcades on double columns, represents a successful combination of Roman heavyness with Genoa ease.

The truth is that in the 17th century in Italy there was no shortage of independent creative architects who informed the buildings of each city, no matter where they were cast, their particular imprint. Therefore, it was Italian architecture that continued to influence the far distance.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)