1. An overview of the new styles in the 18th century France

The main style of French art in the XVIII century is the Rococo, which was widely spread under Louis XV. In parallel with him, the Greek style developed, arising from the desire to return to ancient motifs in art. An important element of both of these areas was the emphasis on closeness to nature.

Chewing and flirting, submitting to women and greedy to women, striving for charm, fun and convenience, the 18th century appeared on the world stage. In all areas of art and life, it was at the beginning a century of further development and fading of the Renaissance and Baroque, which, however, turned out to be still vital enough to spread as the new spirit of the time in the form of a new independent, light and elegant fashionable style; later, however, touched by the spirit of more courageous seriousness, it everywhere became a zealot of turning, plotting a return to either the Italian renaissance, now to the Roman, then finally to Greek antiquity, but at the same time to nature. If Italy remained in some respects the birthplace of this movement, then nevertheless, these transformations were carried out most clearly and fully on French soil. More resolutely than ever, France assumed the leadership of further artistic development.

New, grown from the Italian Baroque Borromini, Gvarini and Cortona, the architectural style of the era, known in German science under the usual name of Rococo, was French. The term "Rococo" was preceded by the name "Rocaille", denoting shell jewelry and artificial rocky grottoes, but, as a style mark, associated, as Geimüller showed, with shell jewelry. Without going as far as this researcher who wants to limit the meaning of the term “rococo” to the swollen “Rocaille” conch-like formations, we mean by rococo not so much the totality of all the styles of the Louis XV era (1715–1774), but the light, fantasy-filled, decorative the style of this era, which, rooted in the “Gali genius” (esprit gaulois), as a new creation, contrasts not only the baroque of Italy and Germany but also the palladianism of France and England. This style, which is used almost exclusively for interior decoration, is an ornamental style that is missing only on the semicircular protrusions of the walls in the form of lisens, which turns all supporting and bearing pilasters of wall divisions into ornamental frames, and all the frames are ornamented, elongated like the letter S from shells, stripes, ribbons, flowers, leaves and branches, eventually evading as much as possible even from the laws of symmetry. Although Schmarsov, in order to justify the common name for the style, it is true that this interior is often caused by a new, free, designed for a more comfortable lifestyle, the distribution of rooms, a more adapted form of living for the rooms and a lighter inside and outside. rounded edges, with an abundance of large windows and double doors, we still prefer to use the term "Rococo" in a very limited sense, already in view of the contradiction with the French. In addition to Shmarsov and Gamemüller, the concept and essence of Rococo was mainly analyzed in Germany by Tsang, Springer, Semper, Dom, Schumann, Gurlitt, and Jessen. The French, however, call the styles of the eighteenth century simply by the names of the rulers. The style of the late era of Louis XIV is followed by the Regency style (1715–1725), the style of Louis XV is the Pompadour style, followed by the style of Louis XVI, which, however, as the Chef points out, manifests itself in the last decades of Louis XV.

This light free style represents, however, even in France, its homeland, only one of the trends of the style of the XVIII century. In some countries, for example in England, Rococo is completely absent, while in others, especially in Germany, it turns out to be stronger and more durable than in France itself. Significantly stronger than the Rococo current throughout Europe, in all areas of life and art, the recognition of the need for a full turn, often seen in the first half of the century.

Art criticism also warned about the turn of art, speaking more clearly than ever. The turn to Greek antiquity, as opposed to Roman, was already prepared in the 17th century by Greek travels and explorations of Jacques Spon and was already prepared in 1706 in the works of Cordemois, although it is still unclear and with numerous concessions to the style of the era. The discovery of Herculaneum and Pompey (1748), which was first reported by Dartena, indicated the whole of Greco-Roman antiquity as a whole.

Next to the turn to Hellenism, a turn to nature manifests itself along the whole line, the inspired apostle of which was Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778). At the same time, this particular turn to nature more than once intertwined with other peculiar impulses. The Rococo style also considered itself a part of nature, in view of the natural freshness that some of his endeavors breathe, and the natural details that he wove into his fantastic frames, and the warming classicism especially willingly declared a claim to new finding of nature, considering the “artless simplicity” to be Greek and at the same time natural, and the Greek temple is directly inspired by nature. It is this peculiar and non-logical comparison of the imitation of the ancient Greeks with the transfer of a genuine nature that gave a special character to the second half of the 18th century. Only a few, such as, for example, the great French critic Diderot, and that only by chance, decided to contradict. “There is nothing mannered,” he says, “neither in drawing nor in colors, if they faithfully imitate nature.” The mannerism comes from the master, from the academy, from the school, even from antiques. ”

The academies, which were now modeled on the Parisian in all European countries and triumphed in the fight against the privileges of the old workshops, had a favorable effect in terms of improving the living conditions of the artists, but they everywhere encouraged the boring, learned correctness, which is called our “academic direction” in a close sense.

2. Leading French architects of the period

During the 18th century, several leading schools and trends in French architecture changed, leaving many distinguished names. Most of the masters in this period work in the Rococo style, by the end of the century classic, more rigorous motifs in architecture came into vogue

Regency Architects

The greatest architect in France in the epoch of “regency” is Robert de Cott (1651–1735), a student and brother-in-law of Jules d'Ardouin Mansart, who completed his palace chapel in Versailles and the Palace of Trianon. The outer sides of its buildings are cold, at the bottom of the Tuscan, at the top of the Corinthian front side of the Oratorio and completed only in 1738 by his son, the classic Renaissance facade of the church of Saint-Roch in Paris, belong to an older and more rigorous direction. His hall Hercules in the Palace of Versailles is the last magnificent marble work of Louis XIV style. In the structure of private hotels, it was Kott who strove for a freer and more consistent basic plan in the spirit of the epoch; it was he who introduced the easier and more lively mode of decoration that prepared the style of Louis XV. His exemplary work of this kind - the restructuring of the Hotel de la Brillard (now the French Bank) in Paris, whose magnificent “Golden Gallery” is one of the most brilliant rooms in France - still retains the complexity of wall pilasters, but in free-flowing and lively individual forms with realistic decorations of the shells and leaves that accompany the pretty figure plastic, should not hesitate to the suggestions of refined artistic fantasy. Outside of Paris, de Cott completed the magnificent episcopal palaces in Verdun and Strasbourg and was the author of the beautiful square of Louis XIV (now Bellecour) in Lyon.

Fig. 200. Robert de Cott. Saint roch church in paris

Of the masters who developed in the same direction as Cott, mention should be made of Calleto the Elder, nicknamed l'Assurans (died in 1724), the builder of a number of Parisian "hotels" with freer distribution of rooms and lighter forms of decorations. With the Italian Girardini, in 1722 he executed the widely spread one-story building of the Bourbon Palace, which, as a meeting place of the French Chamber of Deputies, was rebuilt many times.

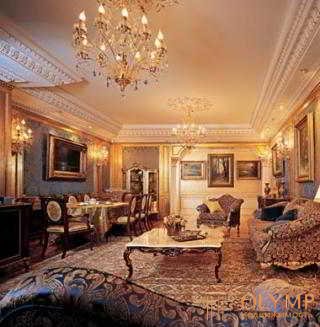

It is most convenient to study interior decorations indicating the further development of Rococo in the halls of the Palace of Versailles, Fontainebleau and the Grand Trianon, newly decorated in the XVIII century, also in some private palaces, of which Hotel Subiz is the most accessible, the current main state archive in Paris. Old French inlay wood paneling, exquisitely carved in rococo style and painted with light colors, replaces here the heavy marble pomp of Louis XIV style, borrowed from Italy. Gallic genius felt his strength here. Many of the best scenery of this kind are known only in the form of painted and engraved, published in voluminous collections, projects of the great masters of this art. The beginning of the movement is marked by a group of artists "Gillot-Watteau", whose decorative designs grew out of the "grotesque" of "Beren-Daniel-Marot", and often without going over to Rococo, turned into the style of Louis XVI. Of its representatives, Claude Gillot (1673–1722) and his great student Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), whose scenery in the form of “monkey cells” remained in Chantilly, became famous as painters and etchers.

Fig. 201. Hall at the Hotel de Subis in Paris, decorated by Germain Voffran

Fig. 202. Nicola Servandoni. Church of Saint Sulpice in Paris.

A more powerful impression, connected with the remnants of the baroque mood, since the latter was generally possible in France, is produced by some of the buildings whose interior has followed the rococo style. The mentioned Hotel Subiz, erected in 1716 by Delamere (died in 1744), with its deep front courtyard covered by Corinthian double colonnades and a powerful Corinthian middle ledge topped with a pediment, does not give an excuse to expect that its rooms are decorated with playful pomp boffran rococo. For all its classicism, erected back in 1734 by Jean d'Arduin Mansart de Jouy (b. 1700), the Doric-Ionic facade of the old church of Saint Eustache is also quite heavy. The Cathedral of Saint Louis at Versailles (1743–1758) by d'Arduin Mansart de Sagonne gives the impression of greater clarity of the whole, more animated details of its Ionic interior and a richly dissected obverse.

Fig. 203. Jean d'Arduen Mansar de Jouy. Facade of the church of Saint-Eustache in Paris

Finally, let us call Francois Cuvillier (1698–1768), who transferred, as we shall see, the rococo style to Germany.

The architects of the era of Louis XVI

The style of Louis XVI is most exquisite in the interior decoration of rooms and their furnishings. Straightness, replacing the twists of the Rococo, slimness and tenderness of the individual, maintained in the strictest taste of dismemberment, it is here that the most comely and light form, however, sometimes somewhat stingy. Lesser Trianon is also a model in this respect. To get a clear understanding of the transformations of style that took place in this area during the 18th century, one has only to compare the library of Louis XVI and the large room of Marie Antoinette in the Versailles Palace with the rococo rooms of Louis XV and the baroque rooms of Louis XIV.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)