During the baptism of Russia by Vladimir Svyatoslavich (988), its northern capital was Novgorod, its southern capital was Kiev.

The first Russian churches, like all old Russian buildings in general, were wooden. Even the Tithe Church in Kiev, built by Vladimir Svyatoslavich in 989–996. and intended to be his tomb, according to the studies of Russian archaeologists, in substantial parts of it was built of wood. Together with the Greek priests and monks, Greek and - as there is reason to assume - Armenian painters and architects came to Russia; the latter introduced stone architecture in the country from the second quarter of the 11th century. As a result, Russian art until the very Tatar-Mongolian conquest in the middle of the XIII century, in fact, remained a branch of the Byzantine, although it differed from it by many features; however, in recent times, scholars have tended to attribute to Armenian models an even greater role in the emergence of Russian architecture than Byzantine ones.

Our acquaintance with Russian art, very little expanded by the book about him by Viole-le-Duc, was greatly contributed by Novitsky's essay and the luxurious editions of Butovsky, Aynalov, Redin and Suslova. We follow them in our further presentation, partly based on our own memories of traveling to Russia.

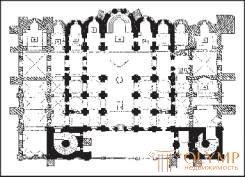

In ancient Russian art, architecture played a pivotal role. The Chernihiv cathedral is the oldest surviving Russian churches, although it only has the lower parts of the walls and pillars of the original masonry, namely the first third of the XI century. It was a four-column church, with a dome alone, resting on a high drum, with one narthex and three semi-circular inside and outside abds on the eastern side. Then among the most ancient Russian stone churches belong the Sofia cathedrals in Kiev (Fig. 123) and Novgorod, of which the first was rebuilt in 1037, and the second in 1052. Both of these original churches with their close pillars in a wide main parts of the building - in front of the domed space like a transept, resemble the church of Sts. Nicodemus in Athens and at the same time Western basilicas. Each of the five naves of Kiev and three naves of the Novgorod Cathedral ends in the east with a special apse. Both temples, however, are so modified by later extensions that only a small part of their interior, covered with just one flat dome and animated by mosaics and fresco paintings, still creates some idea of the former grandeur of these structures.

Fig. 123. Plan of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev. According to Novitsky

Russian churches of the 12th century have a slightly different character. The new capital, founded in 1116, Vladimir-on-Klyazma, reached its highest prosperity at that time. In it between 1138 and 1161. a large cathedral was built in the name of the Assumption of the Virgin. He was still similar in plan with the Novgorod Sophia Cathedral, but the canopy vaults of his naves, not even masked by the roof, form semicircles on the front side, connected by high thin semi-columns into blind arcades. This architecture was probably invented by Lombard architects, who at that time were often called to Russia. They were joined by the Russian architectural school, the monuments of which are the church of the Suzdal monastery built in 1176 and the famous Dmitrievsky Cathedral in Vladimir (1194–1195), restored in the 19th century in its former style. Its southern, northern and western facades are dissected by high deaf arcades. At the top, instead of the crowning eaves, the facades end with three semicircular gables. The lower tier of the building is separated from the upper arching frieze encircling the entire church, the semi-columns of which are supported by brackets from the bottom. The details of this cathedral are akin to the Western Roman rather than the Byzantine style.

To a greater extent, this can be seen in other buildings of approximately the same time, for example, in the chapel of the Bogolyubov monastery near Vladimir, which looks quite “Romanesque”, and located not far from there, on the Nerl, Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin, whose portal in the form of a semicircular arch above the Corinthian columns is decorated with rows of uniquely stylized acanthus leaves. Further to the west, in Pskov, the church of the Spaso-Mirozhsky Monastery, as well as a simple, four-column Chernihiv cathedral, equipped with three semicircular absides, has on each side a strongly protruding triangular pediment, recalling some Armenian churches (see fig. 69 and 70). The Tatar-Mongol sovereignty, established in the middle of the 13th century, subsequently introduced into the Russian architecture many foreign motives, on the basis of which the national Russian art was developed.

In the twelfth century, Russia also reflects a change in the Byzantine understanding of forms. In the mosaic of the church of the Mikhailovsky Monastery in Kiev, built in 1108, where Christ is depicted, communion with the apostles at the Last Supper, we meet the same long-stretched, halohol figures that are common in all oriental art of this era. But in the frescoes of the Kirillovsky monastery in Kiev, founded in 1140, in the movements of the figures and facial features more coarse Slavic features appear, from which the frescoes of St. George’s Church in Staraya Ladoga are not free.

Miniature painting was first cultivated in Russian monasteries by some Greek monks, but Russian calligraphers soon joined them. The Ostromir Gospel (1056–1057), which is stored in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, is considered the most ancient, truly Russian illustrated manuscript. His miniatures with figures, despite the fact that the faces of some of them have a pronounced Slavic type (for example, the image of the Evangelist Mark), are still Byzantine in character. Occasionally there are initials composed of leafy, floral, and animal motifs and made in a mixed North Byzantine style; they are often seated with animals or female heads in the form of masks. Ornamented initials and screensavers of Russian manuscripts, formed from woven floral and animal forms and brightly colored (red and blue colors predominate), until the middle of the XIII century, retain their whimsical character, which differs from the character of the Byzantine manuscripts.

Little can be said about Old Russian plastics. The famous Korsun Gate in the Novgorod Sofia Cathedral is a German work of the twelfth century; Western Russian style with an admixture of Slavic elements is also visible in the sculptural adornments (“prileps”) of the Dmitrievsky Cathedral in Vladimir and the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl. Extremely curious is one of the reliefs of St. Vladimir's Cathedral. Dmitry, depicting Alexander the Great Sky Climbing on a chariot drawn by a vulture; comparison of this relief with a similar image in the Venetian Cathedral of St. Mark, who served as a model for him, clearly shows how the exquisite Byzantine forms became coarse and heavy under the hands of Russian masters.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)