Belief in a single invisible God, whom it is even a sin to represent in human form, conviction in the inevitable predestination of fate awaiting every mortal, and hope for eternal life, in which the believer is rewarded for all earthly hardships with a thousand sensual pleasures - these were the guiding stars shining the hordes of the Arabs, when they in VII. n e. they conquered half the world to themselves and the teachings of their prophet. Mahomet died in 632. A quarter of a century after Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Persia and Rhodes were already at the mercy of the Arabs; then, as if by himself, he obeyed the entire north of Africa, and when in 750 the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad hereditary caliphs whose residence was Damascus, Abdarrahman, the last caliph of this kind, fled to Spain and founded an independent Cordoba caliphate there. The Abbasids, who owned the Arab state from 750 to 1258, moved their residence from Damascus to Baghdad, where under Harun al-Rashid (786-809), a powerful contemporary of Charlemagne, Arab identity reached its peak.

After the death of Harun al-Rashid, the disintegration of the Arab world monarchy into various Mohammedan branches began. Egypt gained independence in 868 with the Tulunid dynasty, Persia - in 870 with the Saffarid dynasty; Sicily became an independent emiracy under the Egyptian Fatimid dynasty (from 969), but already in 1090 this island, due to its conquest by the Normans, was finally lost to Islam. In 1070, the Turkish rule of the Seljuks began to spread in Syria and Asia Minor. The crusades were a vain attempt by the West to break the power of Islam and its followers. From the beginning of the XIII century, the Mongol-Tatar hordes of Genghis Khan and his successors began to flood the countries conquered by Islam. In 1258, the Mongols finished the conquest of the Arab caliphate with the capture of Baghdad. But by adopting Islam, they introduced new blood and life into Arab culture. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Ottoman Turks, being oppressed to the west, conquered the Balkan Peninsula; in 1517, Egypt also submitted to them, and although in Spain the rule of the Moors was forever put an end to the end of the 15th century, but to this day, as 600 years ago, the banner of the crescent still flies over the buildings of Constantinople.

In India and further in the East, Islam began to spread from the end of the XII century, first through the medium of the Tatars, and then the Mongols. The great Mongols who ruled India in the 16th century professed the teachings of the Arab prophet; therefore, in it, as in Persia, during the XVI and XVII centuries, the Mohammedan or, rather, the semi-Magemetcan arts and sciences flourished in a peculiar way.

To recall this course of the spread of Mohammedanism was necessary for us to form the concept of how many different elements formed the art of Islam in its different fields, most of which initially had their own art. Only the Arabs did not have their own art, something worthy of attention. Therefore, when they had the need to build churches, they everywhere used the services of architects from the peoples they conquered, and also where they found, as, for example, in Syria, Christian buildings that could be adapted to the needs of Arabic worship, did it without much reasoning.

The community of religion has caused a common basic spiritual views, reflected in art. The internal connection between the various successors of Hellenic-Roman art, with whom Arabic art touched everywhere, was strong enough to initiate developmental processes related to one another; for its part, the similarity of local and climatic conditions, among which arose the art of Islam, led, with the same construction needs, to similar ones everywhere, although not entirely identical artistic results.

Islamic art is mainly architecture, artistic and industrial production, and related ornamentation. Sculpting and painting did not develop, because the Mohammedan religion does not allow depicting anything alive. True, thanks to the research of Shaka, Karabasek and Gaye, we know that the direct prohibition of paintings and statues is found only in the oral sayings of the prophet, not recognized by all Mohammedans, and therefore this prohibition was not considered either in the first times of Islam, or later, in free-thinking provinces. However, there is no doubt that the national disgust of the Arabs from the images of any living beings really made a big gap in Islamic art with an almost perfect exception to it of paintings, and sculpture, especially round plastic, suffered from this prejudice even more than painting, which has a less "physical" character. Nevertheless, from countries that converted to Islam in Persia and India, painting achieved some prosperity, but only after they were conquered by the Mongols, who brought with them Chinese influences and formed a new art within Islam, which had very little in common with Arab traditions. Even Muslim miniature painting of books, which Ed. Bloche devoted a great article to the "Gazette des beaux-arts", flourishing mainly east of the Euphrates.

The basic principles and forms of Mohammedan architecture and ornamentation originated from the Byzantine art of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, from the Coptic art of Egypt and from the Sassanian art of Persia, which all, in turn, evolved from Hellenic-Roman art. We are already familiar with Sassanian art. Byzantine and Coptic art, as branches of art of the early Christianity, will be considered in the second volume. Nevertheless, it is necessary now to briefly note some of the main features of their architecture and ornamentation.

The Byzantine architecture developed mainly a dome, and since usually the main dome covered the average space of a building, it soon developed a type of centrally built buildings. The dome rested on four or eight pillars. The wedge-shaped segment of the sphere (sail, or pandante) served as a transition from the quadrangular or octagonal shape of the lower part of the structure to the roundness of the upper part. On the columns supporting the arch, instead of an entablature with a release, as we find it in the basilica of Maxentius and in the terms of Diocletian in Rome, sometimes a special "impost" or "pillow" appears, a piece of stone with four trapezoidal edges, placed between the capital and the fifth arch ; accordingly, the capital itself quite often takes the form of a cube with edges beveled downwards. However, this Byzantine cubic capital did not oust the ancient Corinthian capital decorated with acanthus leaves from the Byzantine architecture. Both forms found their use one next to the other. Acanthus leaves on the cup-shaped capitals became smaller and sharper and more and more geometrized. Lateral surfaces of cubical capitals began to be decorated with symbolic signs or flat stylized leaves.

Fig. 638. A capital with an extension. From the temple of sv. Sofia in Constantinople. According to wrigle

On the walls began to appear also more flat patterns, often filled with mosaics. In all this Byzantine flat ornamentation, the state of which is masterfully described by A. Wiegle during the transition from Roman art to Arabic, the main role is still played by an ancient wave-shaped plant tendril in a modified form, inorganic in the sense of plant form, but logical in a geometric sense. Whole leaves are now cut into three strips or into several strips with swollen contours, and "these three-lobed and four-lobed (or multi-lobed) leaves", as Wrigl put it, "fit into different configurations of the space that should be filled with them" (Fig. 638 ). But all these leaves, cut into pieces, can be arbitrarily ornamented by folded together and bent in all directions, until the neighboring stipules intertwine and intersect with them with their cusps. Patterns are formed, evenly distributed over the entire surface, and the antennae, of which these patterns are composed, are no longer combined into circular patterns, as in Greco-Roman art, but into pointed-oval, often diamond-shaped grids. A purely geometric pattern connects with the vegetative, and the ribbon plexuses, which often lead to it, are broken or bent. In all of this, Byzantine ornamentation turns out to be the immediate predecessor of Arabic, or, as others say, Saracenian ornamentation.

With the Coptic art , that is, the Egyptian early days of Christianity before the conquest of the Nile Valley by the Arabs, to some extent we were acquainted mainly with the writings of Al. Gaye, G. Ebers and A. Rigla. It is fully proved that Egypt is littered with ruins of Coptic churches and monasteries of the 6th-9th centuries; moreover, Gaye proved that Coptic architecture was opposed to Byzantine in two respects. She neglected the dome in favor of flat terraced roofs and a circular arch in favor of the raised and broken, often turning into a real pointed, but which usually had only the constructive meaning of a “brick beam”, that is, it was only a special kind of column connection with a column in which the resting on the arch, the wall ended at the top completely straightforward.

We find the Coptic ornamentation mainly on numerous fragments of walls belonging to the aforementioned centuries and taken from Egyptian sarcophagi. For these fragments, its ancient origin is as obvious as the ornaments in Byzantine art; it is reworked in the same direction as it is there: it consists of simplifying many classical patterns, returning to the geometrization of some individual motives and, finally, developing the polygonal system, which is again in Arabic and Moorish arts.

Of course, the question still remains as to how correct the opinion of Gaye, who asserted that Coptic art developed separately from Byzantine and had a predominant influence on early Arabic art. Rigl, who sharply diverged in his views with Ebers and Gaye, did not see in the development of Coptic and Byzantine art any significant difference regarding the formation of plant ornaments. Julius Franz-Pasha also considered the Byzantine and Sassanian influence on the development of the art of the Arabs stronger than the Coptic.

The most important works of Islamic architecture are mosques and madrasas, that is, religious schools, which have always been connected with mosques, and often with cameras above the graves; In addition, palaces, hotels (caravanserais) and tombs (mausoleums, turbs) play an important role in it. The main components of these buildings are courtyards surrounded by arcades, flat-coated halls and for the most part with a multitude of columns interconnected by arches over which they usually support the upper part of the wall, and finally the building under the dome that became the property of the Muslim architecture only over time and with various changes in its form.

Muslims consider their mosques not the dwellings of a deity, but prayer houses. Actually, the temple was always with them Kaaba in Mecca, and the thoughts of the faithful rush to it during prayer. Therefore, the main axis of the prayer hall (Mirhab) is always directed to Mecca. The prayer hall, being the main part of the sanctuary itself, either had a flat roof, or was crowned with a dome, adjoined from the side facing Mecca to a large courtyard surrounded by arcades and intended for ablutions, and towered above it in several steps. Often the sanctuary consisted of only enlarged rows of arcades on the prayer side of the courtyard. Minarets, slender, beautifully dissected towers, surrounded by balconies, appeared, as well as domes in mosques, already in an era of full development of Muslim art: there were no domes or minarets in the prayer houses of the first era of Arabic art. In any case, these elegant towers, rising high against the blue sky over the cities of the East, are among the most original creations of Islamic art that meet the immediate needs of a new religion.

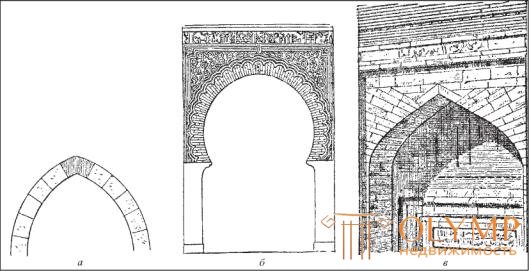

Fig. 640. Forms of arches: a - Egyptian lancet; b - Moorish horseshoe; in - Indian keel. According to Franz Pasha (a, b), Schnase (c)

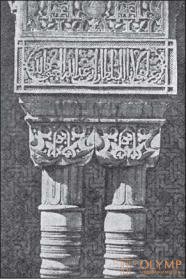

Fig. 639. The columns of the Courtyard of the Lions in the Alhambra. According to Franz Pasha

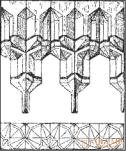

Architectural forms in this art do not differ constructive sequence; even traditional forms have for the most part only a decorative meaning. The outer walls of buildings are usually just plain. For the most part, they are standing right on the ground, without a cap; they do not even have eaves dividing longlines, and the stripe of frieze encircling them, over which the augmenting back teeth are raised, replaces the main eaves of the architecture of western countries that come forward. But the smooth surface of the wall is enlivened by alternating rows of multi-colored stones; its monotony is violated, moreover, by niches, balconies, doors and windows of luxurious and varied shape. Columns inside the building, bearing the weight of arches, mostly smooth-bore and relatively low. Where it was convenient, they were replaced with antique or Byzantine columns, which were intermixed with each other extremely randomly, which apparently indicates the absence of any thought at first about the organic development of the architecture of Islam. Only for centuries has something like a trunk been developed, from several rings of the foot, from many rings on the neck, from a cubical capitals, which is curved below and decorated with arabesques on the sides (fig. 639). In the arch, the semicircular shape is almost always avoided. In order to increase the columns and ease the gravity of the upper part of the wall, the arches were preferably given an upwardly extended shape. The elevated circular arch is often found, but more often it is replaced by a broken, pointed arch, which in Egypt had a two-pointed capstone common to both thighs of the arch (Fig. 640, a); There is also often a horseshoe arch (b), the thighs of which, since its outline is somewhat larger than a semicircle, are bent downwardly inward, in its span, and a wedge-shaped arch ( c ) formed by the connection of the horseshoe-shaped and lancetated arches, turned keel up. The real lancet arch is most often found in Egypt, horseshoe-shaped - in the Mauritanian north of Africa and in Spain, keel - in Persia and India, where we saw it in the ancient Buddhist era (cf. p. 647 and fig. 560). But come across and much more artistic forms of arches. The trefoil arch is a combination of three small arches into one main one. The serrated arch, which is found in various forms, consists of many small arches, the thighs of which, converging one with the other, form on the inner edge of the arc the teeth hanging downwards. Both columns and arches often connect in two and more than two, or intertwine with one another and take extremely diverse and fantastic forms. In parallel with the arch, the dome also developed. The simple, elongated, ovoid shape of the Sasanian dome is rare. Pointed in the section, the dome belongs mainly to Egypt, pulled downwards, horseshoe-shaped, from Spain, keeled, taking the form of an onion, pear, or other fruits — Persia and India. A feature of developed Islamic art is the dripstone (stalactites) or cell-covered vault-like honeycomb, which, while not constituting a constructive whole with the building, but being carved out of wood or molded from plaster, again expresses the decorative character of Arabic art. This is nothing more than a circular plastic metamorphosis of the dentate arch: the arch splits into a large number of small domes or vaulted cells, the side walls of which, meeting one another at an acute angle, hang downwards in the form of stalactites (Fig. 641). Stalactites were used to decorate not only niches, as well as half-domes of another type; even the capitals of the columns (fig. 642), the arches spans and the crowning cornices are sometimes ornamented with stalactites.

Fig. 641. Cairo stalactites. According to Gaia

Fig. 642. Cairo capital, decorated with stalactites. According to Franz Pasha

Wall decorations inside buildings are mostly flat and even in-depth, carved and through; despite the slight elevation of their pattern, they do not lose this character. The surface finish of the outer and inner walls is often made of tile, i.e., burned clay tiles, often of knock or plaster, often also of wood, and wooden carving on canopies, balconies, cornices usually keeps simple ornamental motifs peculiar to its technique, while the side the surfaces of chairs, cabinets and drawers are decorated with the most luxurious flat patterns.

From the 12th century, when decorating buildings, elegant glazed terracotta tiles, or tiles, which were known to Egyptians, Babylonians and Jews in ancient times, were forgotten, but then during the rule of Greek art were forgotten, and in the first centuries of Islam were not yet known, least as a material separate from building bricks. It appeared in Islamic art suddenly in the XI or XII century, where exactly for the first time it was not yet possible to establish, in Egypt or in Persia. The tile consists of sintered burned clay, which, thanks to the glaze, has received impermeability and strong gloss of its color. In this faience, the baked clay is covered with an opaque layer of tin glaze, and its mass is painted all in any color or it is painted on the finished surface with paints specially used for it before firing. The same way to apply paint on the annealed glaze, to then subject tile to a third fire, is called a muffle painting. Through muffle painting, metallic luster is produced on special-type earthenware earthenware, which is called lustrized earthenware or metal-tipped faience. Lustration was in use most of all in Persia and Spain. The golden luster of the glaze at the time of the decline of this technique turned more and more into copper. A completely different kind of clay products is obtained by coloring the burnt clay vessel under the glaze, right on the background of the clay, if it is light enough; otherwise, painting is done on a special layer of milky-white watering, after which the vessel is covered with a colorless, transparent glaze. From silica, which in this case should be contained in the mass of clay and in the glaze, such products received from the English (and French) name silicious glazed pottery, while Otto von Falke called them simply semi-faience. Islamic art used the faience of all these generations not only in architecture, but also in the manufacture of dishes. A special type of tile is mosaic plates, used mainly in Persia, but also in Asia Minor and Turkey: curvilinear figures are cut out of glazed monochrome plates, and then patterns are made of such multicolored pieces.

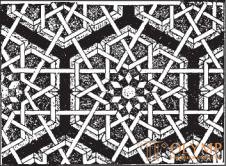

Fig. 643. Arabic ornament consisting of interlaced polygons. In the Sultan Hasan's madrasa mosque in Cairo. According to Gaia

All the eastern flat ornamentation in the form in which we find it on the walls of the Mohammedan buildings, despite its obvious origin from the Byzantine, Coptic, Sassanian, as well as Hellenistic-Roman models, belongs to the greatest and most original creations of Islamic art. The main components of Arabic ornamentation are, first of all, geometric figures of every kind and kind, not only straight, but also spiral, arcuate, curved inward and outward, triangular and polygonal, which are in various artistic combinations and interlacing (Fig. 643), then ribbon nodes and loops, which were used more often for dividing the surface into fields in the form of a grid than for filling individual fields, and finally, arabesques proper (Fig. 644), which received this name as the main component of the Arabic ornament muffles. Arabesques, as a kind of strictly stylized pattern of plant curls, have long been known. But only A. Rigl in his essay "Questions of Style" for the first time proved that they are nothing more than a pattern of the antennae of the Hellenistic-Roman acanth stylized to fill large, interconnected planes that need to be ornamented according to the main rules of continuous weaving to infinity. How this stylization occurs in individual cases, we have already seen in Byzantine ornamentation, the immediate predecessor of the Arabic (see Fig. 638). Arabic art used the newly acquired forms more strictly and more logically, gave them incomparably more luxury and fantasticalness than the art of the early Christianity in Byzantium and Egypt, which generally sought simplicity. Another random, especially loved only in some places, components of Mohammedan ornamentation are plants in their natural form (Fig. 645) - leaves, flowers and fruits in a new, easy styling and stylized figures, fantastic or really existing, even human figures and, finally , everywhere sayings from the Qur'an, inscribed or rectilinear kuficheskie (Fig. 646), or rounded Arabic characters.

Fig. 644. A piece of the board in the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo. According to Pris d'Avennu

Fig. 645. Arabesque with flowers. According to Gaia

All these forms of Arabic ornamentation are inserted into a grid of geometrical figures, consisting either of rhombus, now of quadrangles, now straight, then curved in various ways, and moreover, they are enlivened by luxurious coloring, which clarifies and separates the individual constituent parts of the pattern. The basic law in Arabic art is the filling of whole strips and whole planes to be ornamented with the same pattern and a uniform distribution of lines and colors on the surface. Constantly evolving, Arabic ornamentation has shifted from relatively simple to extremely complex and lush patterns of this kind, intertwining in the most amazing way. In the developed Arabic-Moorish-Saracenic ornamentation, which is in all its splendor not only in architecture, but also in ceramics, in illustrations of books written on parchment or on paper, in wood and ivory carving, in metal notches (" Damask ", especially in the manufacture of weapons) and in weaving, shows a strictly calculating mind, combined with a lively fantasy; wise sayings borrowed from the Qur'an or from poets and turned into motifs of ornament, for their part, breathe the living spirit of the Arab national genius, all of whose wisdom is expressed in verse: "There is no God but God, and Mohammed the Prophet!"

Fig. 646. Arabesque with kufic inscriptions. According to Gaia

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)