Apart from Mecca and Medina, in which the most ancient of the buildings do not represent anything artistic, the first and most ancient activities of the Arab artists were Palestine, Syria and Egypt.

The eight-sided "dome of the rock" (Kubbat al-Sakhra) in Jerusalem, a building topped with a wooden dome and containing the rock of Abraham, of course, cannot be the mosque Omar built here in 637, although the inscription in it reads , that this construction of the Umayyad, belonging to the first century of Islam. The building was renovated many times, but in its original form and in character it is a Byzantine central-dome structure; The columns placed between the pillars forming two concentric rows of props inside the building are taken from more ancient buildings. The Al-Aqsa Mosque ("the most remote sanctuary"), located near this "dome of the rock", was originally a seven-nave Christian temple, in its present form, after its repeated defeats, was erected from the ruins only in 1236. Above the middle of its transverse nave rises dome. Its architecture is not yet Arab.

A large mosque in Damascus, considered by Muslims to be a wonder of the world, was at first also a Christian church; the alteration of it into a mosque, performed during the Caliph from the Umayyad Walid house at the beginning of the 8th century, was made with the help of Byzantine artists, and the ancient columns with which it was decorated were written out from Syria. It was restored in 1893 after the fire that befell it. With three longitudinal naves and a dome over the middle of the transverse nave, supported by eight pillars, it still gives the impression of a Christian church; from the northern side, it opens with an arcade on a purely Arab courtyard, surrounded by arches slightly upward. The mosaic on the walls of the Byzantine work and is a mixture of landscape motifs with ornamental.

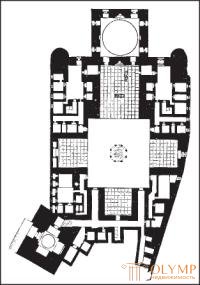

Fig. 647. Plan of the Amr Mosque in Old Cairo. According to Gaia

The type of real mosques was and remains the Medina Grand Mosque. It was also completed under Caliph Walid. Only in accordance with the needs of the faithful, this mosque consists of a quadrangular courtyard, surrounded on three sides by four, and on the south side, on which the faithful gather for prayer, in eight rows of arcades. The plan of a real mosque, with a large front yard, a monumental pillar hall, with a crypt-like main sanctuary, a prayer niche, somewhat resembles the plans of ancient Egyptian temples, although the continuity of the relationship between them and it cannot be proved.

It is possible to trace the development of Arabic art in Egypt better than anywhere else, thanks to Priss d'Avenna's great work "Arab Buildings in Cairo", which introduced Europe to this subject in the middle of the 19th century. The mosque of Amr, built by the Coptic architects on the orders of the commander of Omar, Amr Ibn al-As, soon after the conquest of Egypt (in 642) on the outskirts of Old Cairo, was rebuilt so often that its original design did not leave a stone on the stone. But its restructuring was always carried out according to previous plans, and therefore it still gives us an idea of the location of this ancient mosque without domes and minarets (Fig. 647). In it, as elsewhere, in the middle of the courtyard there is a pavilion with a well. Columns of its arcades are also taken from various antique buildings. The arches that support the upper part of the walls, on which the flat ceiling rests, have an arrow shape. In the oldest part of the preserved exterior walls there is a perfectly pointed window. Inside the building, from the entrance side facing west, there is only one row of arcades on the columns; on the north and south sides of the courtyard of such arcades are three rows each, and the prayer gallery, which extends into the hall with columns and occupies the eastern side, consists of six rows of arcades.

Fig. 648. Type of arabesque: a - arabesque from Ibn Tulun mosque in Cairo; b - alteration of this pattern back to the Greek. By al. Wrigl

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.3 people play!

Play gameThe Tulunid dynasty (868-905) was followed after the interregnum by the Fatimid dynasty (909-1171), who loved the pomp, who dominated the arts and decorated Egypt and Palestine with palaces, one description of which responds with a fairy tale, and mosques, whose architecture, keeping the old master plan, became more and more luxurious. Arches in them are more correct and slimmer, more expensive materials are used for wall cladding, arabesques on ornamented strips and planes are developed first only over the tombs of the founders of mosques built during these buildings. The tomb of Giyushi mosque on the Mokkatam Heights, near Cairo, is known as a dome building of this epoch. We can judge the development of ornamentation best of all by some of the fragments of jewelry collected in the Cairo Museum.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.3 people play!

Play game

Fig. 649. Plan of the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo. According to Gaia

Arabic-Egyptian architecture and ornamentation reached full brilliance during the rule of the Mamluks. The carved wooden doors of 1285 from the Muristan Hospital, described by Pris-d'Aven and now kept in the Arab Museum in Cairo, show that, at least, in civil buildings of this time they did not find it difficult to weave animal and human figures into arabesques. Of the sultans of the Bagrid dynasty, the Mamluks, in particular, Hasan (137–1361) were distinguished by their patronage of the arts and sciences. The mosque of Sultan Hassan, built in 1356-1363, contrasts the first, ancient main form of mosques with a flat surface, with a courtyard enclosed by arcades, and with a whole forest of columns, the second main form - the form of a mosque with a cruciform plan covered with a dome (Fig. 649 ), but in which, however, real domes rise only above the builder’s mausoleum, connected to the mosque, and sometimes also over the side premises, as, for example, in the case under consideration above a small entrance vestibule. The main courtyard, in the midst of which the ablution pavilion rises, is surrounded here not by arcades, but by four huge halls, which are covered with pointed basins and open up to their full height and width with huge pointed arches on each of the four sides of the courtyard. Thus, the main form of the plan is an enormous cross, with its simplicity and size producing a striking impression. The southeast hall, the sanctuary itself, deeper than the other three halls, contains a prayer niche; the two aisles near it, which are closed by magnificent doors, lead to the Sultan's tomb, covered with a stalactite-lapel dome. The prayer niche, framed by columns of elegant sculptural work, is magnificently tiled with variegated marble. The walls of the entire southeast hall are decorated with brilliant color mosaic that forms geometric polygonal patterns, and at the top a frieze, which, painted with quotations from the Koran, with its openwork arabesque gives the impression of luxurious work. The Hassan Mosque, although it represents a certain dismemberment in the vertical direction, its massiveness, simplicity and grandeur resembles monumental ancient Egyptian temples. The niche of the pointed portal, covered with a stalactite arch, is one of a kind; The crowning cornice of the building, also seated with all stalactites, can be considered extraordinary.

According to the plan of the Hassan mosque, a mosque of the Sultan from the Mamluk dynasty of Borguk borghides (1382-1399) was also built, whose daughters were buried under its domes. But here the sacred southeast hall is divided by columns again into three naves. Even more beautiful than this "Barkukiye" is the nadmogilny mosque of the same Sultan, located in front of Cairo. According to its plan, this is again a mosque with a courtyard surrounded by arcades; but the arcades of its main courtyard are completely covered with small domes, while the two main domes are crowned by two tombs. The minarets are decorated with stalactite cornices. The whole building is distinguished by a strict, clear symmetry of the plan and the nobleness of the forms.

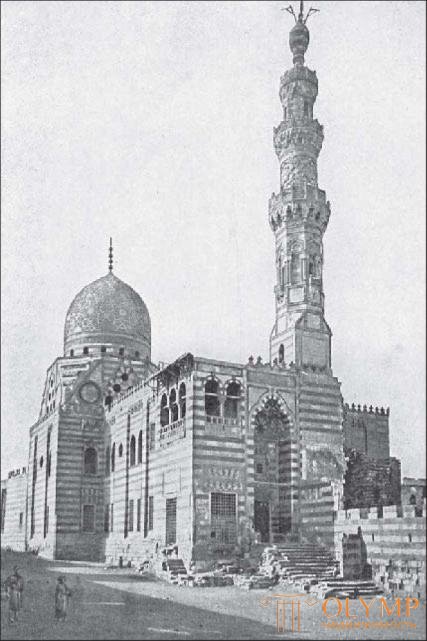

In the XV century, Egyptian buildings become more elegant, especially the minarets. The most beautiful of them is the minaret of the Al-Ashraf Berisbey Mosque in the amber market in Cairo, built in the 1430s. Then you should indicate Kait Bey facilities (1468-1496). His Small Mosque in Cairo competes with his suburban tomb mosque both with the grace of proportions and the wealth and elegance of individual decorations (Fig. 650). The dismemberment of the building is now becoming more pronounced, even in its appearance. The alternating layers of red and white stone, from which such mosques are built, for their part, contribute to the revitalization of the surface of the walls. Inside these buildings, an open courtyard still dominates, with four rooms of a cruciform disposition, each of which opens into it with a pointed arch, and the colored glass in the windows increase the charm of the gloomy lighting of enclosed spaces.

After Egypt became Turkish Pashalik in 1517, the Arabic style gave way to Ottoman-Byzantine architecture. The central building of the temple of St. Sophia in Constantinople became a model for Cairo. The open courtyard has disappeared or was arranged separately in front of the building. The main dome began to lie above the sacred hall. A number of such Cairo mosques begin with a small mosque of Suleiman Pasha, built in 1526 on the northeast side of the citadel, and ends with the Alabaster Mosque of Muhammad Ali (fig. 651), built in 1830-1848, in the citadel.

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.3 people play!

Play game

Game: Perform tasks and rest cool.3 people play!

Play game

Fig. 651. Syrian-Egyptian faience vase with a metallic sheen. By O. Von Falke

Fig. 652. Kait Bey Tomb Mosque in Cairo. From the photo of P. Shah

In the glass industry, primacy, undoubtedly, belonged to Egypt. And in this case the ancient Egyptians paved the way for their medieval descendants. From the time of the Mamluk dominion, mosques began to be decorated with colored window glass, on which, apart from famous geometric figures and arabesques, tulips, carnations and other flowers are often found on long stems and in vases or dark green cypress trees. In the news that has come down to us of this time glass vessels are often mentioned; Quite a lot of Egyptian colored enamelled vessels belonging to the 14th century have survived, mainly lampads from mosques called Kalaun, richly decorated on a gold background with multi-colored sayings and arabesques. For example, in the extensive collection of E. André in Paris was an elegantly decorated glass flask, which Gaia attributed to the XIII century; The lamp of the XVI century was in the collection of Schnitzer.

What the Arab writers tell about the schools of painting and wall paintings that existed in Damascus and Cairo, we can not check. Real paintings in Arabic manuscripts are very rare. However, it is possible to indicate, for example, the illustrated manuscripts of the Macam al-Hariri, the volume of which, written around 1375, is kept in the Vienna Court Library. In it in front of each poppy (story in rhymed prose) placed a portrait of the poet. These images, filled with beautiful colors, without shadows, resemble Chinese and, perhaps, Persian painting of that time. Even in the features of the depicted faces, there is something Chinese, thanks to the outer corners of their eyes raised upwards. The ornaments of some Korans, usually consisting of the finest arabesques, filled with gold, red and blue colors, seem to be purely Islamic. Several sumptuous manuscripts of this 14th century genus are located in the Khedive library in Cairo. But the most beautiful of all is the Koran, belonging to the National Library in Paris. The Arsenal Library in Paris owns the Quran in 1422 with luxurious ornaments on the margins. In this ornamentation of the Korans, images of living beings are not allowed, and often it simply repeats the patterned friezes of mosques; but since the technique of painting is easier than the technique of carved, laid on or composing works that Mohammedan ornamentation uses so magnificently, it is clear that here it achieves amazing luxury, amazes with its soft, beautiful colors and tones, most of all with its fantastic lines.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)