In India, Islam, which first entered the country through the Indus in the 11th century. together with the sovereigns of the neighboring semi-Persian Hasna, at the beginning of the XII century. he began to build his mosques and mausoleums near the Brahmin pagodas, his royal palaces on the site of the ancient Indian royal residences. India became the prey of the Tatars who attacked it from the north, together or separately, the Turkmen and the Mongols, closely related to each other, the Upper Asian tribes who had adopted Mohammedanism, then entered into alliances with each other, then were in mutual enmity. In the first Indian-Mohammedan state, which existed more or less closed, from 1206 to 1526 reigned one after another in a different dynasty. The Turkmen Mamluk dynasty, whose sovereigns were notable for their love for the Qutb-ad-Din-Aibak and Altimsh constructions, replaced the Patanov dynasty in 1290, which the terrible end of the Tatar-Mongol invasion led by Timur in 1398. Timur himself, after taking Patan the capital of Delhi, went back from India, but his descendant in the sixth knee, the Great Mogul Babur, returned to her with a huge army, took in 1526 Delhi and Agra and founded the powerful dynasty of the Great Moguls, who fell only in 1707 during the uprising indigenous hindu ancient brahman skoy creed.

In the history of the arts, all the art of the first Mohammedan-Indian state, from 1206 to 1526, is called the art of the Patans and is considered to precede and opposite to the art of the Mughal people of the 16th and 17th centuries. The main, but not the only, centers were Delhi and Agra-na-Jamne, one of the southern tributaries of the Ganges. In the west, from Cindy and Gujarat to East Bengal, and in the north, from Punjab and Aud, to the southern outskirts of Deccan, domes of mosques and in general many Indian mosques belonging to the most majestic creations of Mohammedan art rise above all Indian cities.

Wherever Islamic architecture penetrated, it would always adjust to local structures, while remaining true to itself. So it was in India. Sometimes it borrowed a plan from Indian pagodas, in which several walled courtyards lay one in the other, and the sanctuary was located in the middle courtyard; the entrances to the fences were often turned into massive gates, and the appearance of the mosques was given a clear and rich dismemberment, like in large Indian buildings; with particular love it imitated the Old Indian wooden pillars in their quadrangular stone columns, the capitals of which from all four sides consist of protruding brackets, and for a long time drove the domes out of horizontal layers of stone, especially where used by Indian workers. The keel-shaped arch and the dome in the form of an onion were transferred to Indian-Mohammedan art from Persia, although the first was already known to the Hindus more than a thousand years before. But the aversion to the introduction of figures of living beings into the ornamentation of buildings brought from Arabia by him, this art sought to strictly observe in defiance of the excessively abundant animal ornamentation of Buddhism and Brahminism. Therefore, when comparing them with the Brahman pagodas, Indian mosques often give the impression of degree, peace, even coldness; as compared with the mosques of the western region of Islam, they are already due to the luxury of hewn stones, of which they are composed, which seem, at least in appearance, more monumental, rich and artistic. Then it should be noted that in India, as in Egypt, the tomb buildings of the Mohammedans sovereigns differ in size and pomp that make them the wonders of architecture. Usually, the sovereigns began to construct tombs for themselves even during their lifetime and planted around them landscaped gardens. Being widely available, these buildings and gardens were in some way gifts of the dead kings to the people. And here a simple sarcophagus is placed under the middle dome, but the halls surrounding the central peace from all sides and opening up free access to it have the most diverse and rich plans.

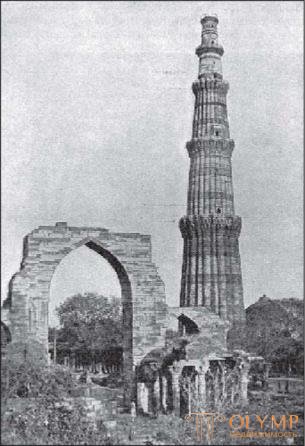

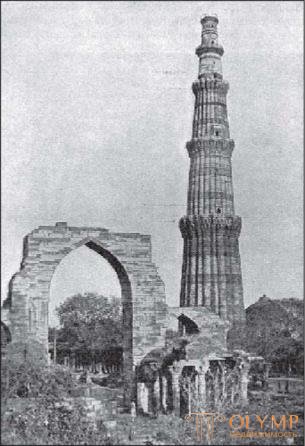

Fig. 662. Qutb Minar in Old Delhi. With photos of Burnet

The palaces built for the residence of the sovereigns of health are less numerous and have not been preserved as well as these palaces of the departed; however, they also eloquently testify to the richness and artistic taste of the Mahometan rulers of India.

Of course, some Indian-Mohammedan structures differ from each other radically, depending on the place and time.

Ferguson counted over 13 different types of Indian architecture, corresponding to the same number of geographical centers. But since both Mohammedan and Indian architecture have already experienced their century-long evolution at the time when they collided with each other, it is difficult to trace the organic course of development using these features.

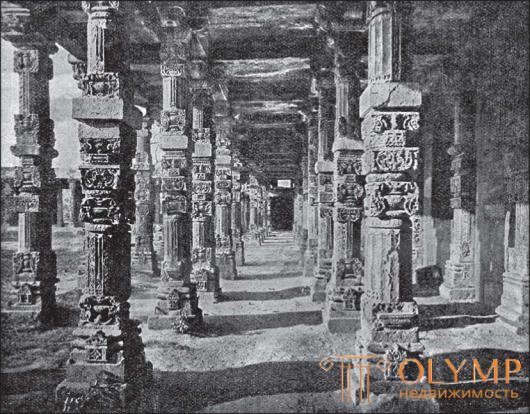

Fig. 663. Gallery with columns in a mosque next to Qutb Minar. With photos of Burnet

Close to this mosque are the tombs of Altimsh (1235) and Patan Ala-ad-Din II (1310), which, due to the rich ornamentation with arabesques of its walls and the construction of keeled arches, despite its small size, belongs to the best constructions of the Patanov style .

In Jaipur, a provincial city on one of the northern tributaries of the Ganges, the mixture of the Mohammedan and Old Indian forms continued throughout the 15th century: the Friday Mosque is remarkable for its enormous gateway, semicircular domes and at the same time, keeled arches, as well as high-rise galleries on four-sided columns flat-coated capitals of these pillars, whose luxurious brackets stand out strongly and still have an Indian character with the pillars.

The Friday Mosque in Ahmedabad also belongs to the 15th century, in which the Indian features of the Gujarat province style are shown with particular purity. Horizontal lines prevail in it. Minarets are not available. The sanctuary occupying the western short side of a large rectangular courtyard consists of five domed halls in one connection, all of which open to the courtyard, and the middle one is higher than the others. Keel arches and domes have only a decorative meaning. Flat ceilings throughout this mosque are supported by quadrangular pillars with plastic-trimmed plinths and clearly marked brackets on the capitals. The architecture of this building has not yet gotten away from the style of wooden buildings.

Luxury buildings in Mandu, in the Malva area, also date back to the 15th century. The main mosque consists of a courtyard, which, as in ancient Egyptian mosques, is bordered on the entrance side by two, on each of both sides adjacent to it by three, and on the prayer side by five arcades. The arcades consist of monolithic pillars of red sandstone and of the actual pointed arches they support. The sanctuary on the prayer side is decorated with three large domes; smaller domes cover the square spaces that make up arcade galleries. Only a few other mosques surpass this in terms of grandeur and at the same time simplicity.

In Gore, the Mohammedan capital of Bengal, is a mosque of the mid-XIV century, built mainly of brick; short and thick stone pillars support brick arched arches and arches in it. The mosque in the neighboring town of Maldah, belonging to the second half of the same century, was built entirely of brick and is a building covered with no less than 385 low domes and distinguished by characteristic, but also with some uniformity of Mohammedan forms.

In South India, on the Deccan peninsula, in Kalburg, there is a mosque built in 1400, the only one of its kind, as it is completely covered and opens from three sides to the outside with a huge gallery with keel-shaped arches stretching to the full height of the building. Then, in the 16th century, Bijapur, a city in Deccan, was a place where magnificent buildings were erected in a special, bold style, with pointed arches and arches, which no longer contained anything indian, but which, like the then owners of Bijapur, had no claim to European origin. The sanctuary consists of five rows of arcades, going from east to west, and from nine - from south to north. Transition wedges from the quadrangular central part of the building to its large dome are equipped with ribs. Even more enormous is the dome of the magnificent tomb of Mahmud in Bijapur: it is wider and higher than the dome of the Roman Pantheon, and the transitional wedges from its quadrangular bottom to the roundness of the dome are very artistic. Finally, mention should be made of the auditorium in Bijapur, which, in its keel-shaped entrance arch with a height and width of 27 meters, is one of the most daring, though perhaps not the most beautiful structures of its kind.

From the buildings of Bijapur, we can go directly to the buildings of the Great Mughal of the XVI and XVII centuries. They are located mainly in New Delhi and Agra. Their magnificent correct plans, the developed system of stone pillars and keel-shaped arches, the colored onion domes, the jewel of the materials used on them and the luxury of mosaic decorations make up something new, something that could be, if you like, called the Mohammedan Renaissance. However, in this style of the Great Moguls it is possible to trace the significant development consisting in the transition from a conscious fake under ancient Indian originality to a more general correctness. The buildings of the great emperor Akbar (1556-1605) represent in this respect a certain contrast to the buildings of his grandson, the emperor Shah Jahan (1627-1658).

The main mosque of Akbar stands on a high terrace in Fatih-pur-Sikri, the beloved residence of this sovereign, not far from Agra. To the huge courtyard, surrounded by arcades, on the west side adjoins the sanctuary, crowned with three domes. The gates are especially huge - located in the middle of the courtyard; the largest of them are southern; The keeled arch of their opening forms a niche topped with a half-dome, occupying almost their entire facade: the door leading to the mosque is located in the depths of this niche. Such buildings have already met us many times in Islamic architecture; in them the need to endow the building from the outside with a monumental entrance corresponding to its height is satisfied in an extremely artistic way, and at the same time to arrange an ordinary, convenient passage for people from the inside.

The main tombstone built by Akbar is his own, located in Sikandra (Sikundra). It shows the imitation is not so much the ancient Cambodian, as the ancient Indian tombs. This is a massive, rectangular terrace-shaped building, each of the upper tiers of which, opening outwards with lancetted arcades, is smaller than the lower one. On the four sides of the lower tier stands at the monumental gate; in the corners of each terrace are pavilions, topped with small domes; but the central dome, which would dominate the whole building, does not exist.

Typical of the palace buildings of Shah Jahan is his Grand Palace in Delhi, the back side of which is reflected in the yellow waves of Jamna. The portal of this palace, 120 meters deep, resembling the middle nave of a huge Gothic cathedral, is considered the most majestic palace entrance. Behind this portal lies a vast square, enclosed courtyard, on the sides of which, to the right and left, are long galleries adjacent to it; in this courtyard is another, rectangular courtyard, around which halls and rooms are located. Some halls, such as the audience, are separate small buildings. The inscription in this room, the most elegant room in the whole palace, reads: "If there is heaven on earth, it is not in any other place, but only here."

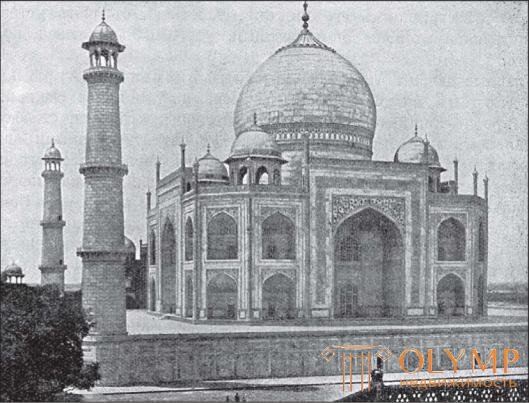

As a type of Shah Jahan tombstone, you can point to the Taj Mahal in Agra (that is, the wonder of the world; fig. 664). The tomb itself occupies the middle of a huge rectangular terrace with four towers at the corners and luxurious annexes. The mausoleum itself is square in plan with cut corners; on this square there is a series of round and cruciform halls in plan, connected by passages between themselves and with entrance niches opening outward in the form of keel-shaped arches around the central room. The central room, the largest of all, has an octagon-shaped plan and is surmounted by a dome. This last one is double: the inner one has the shape of a hemisphere, the outer one, designed only for the external effect and dominating the whole building, lies on the vestibule and its shape resembles a bulb. All parts of the building are decorated with inlaid and carved marble. Even the window frames of the central octagonal room are made of marble slabs, cut through with a luxurious pattern. However, it is known that these marble works, if not all, then at least in part, are made by Italian and French masters, drawn by Shah-Jahan to Agra.

Fig. 664. The Taj Mahal in Agra. With photos of Burnet

Thus, this building brings us back to the border of pure oriental art. In fact, soon after the construction of the Taj Mahal, the influence of Europe began to uncontrollably pave its way to Indian architecture. It was reflected in the tomb buildings of Golkonda, Maisur and especially Luckow, the main city of the northern Indian province of Oude. The bastard style of luxurious buildings in Lucknow belongs, however, already the XIX century, testifies to the complete decline of Indian architecture: European styles, imposed on India by the British and its winners, did not contribute to the country any new ideas, healthy development of art.

Если не принимать в соображение скудных пластических украшений некоторых мечетей, то придется сказать, что магометанской скульптуры в Индии не существовало; но эта страна, подобно Персии, имела свою магометанскую живопись . Как и в Персии, кроме позднейших нехудожественных изображений на стенах она производила главным образом книжные иллюстрации и портреты, исполненные на бумаге.

Наряду с такими работами большой любовью пользовались в Индии писанные на кости миниатюры, отличающиеся тщательной выделкой всех аксессуаров. Общепризнано, что эти книжные иллюстрации и миниатюры до такой степени проникнуты персидским влиянием, что нередко бывает трудно или совершенно невозможно отличить их от произведений современной им персидской живописи. Л.-Г. Фишер, написавший в 90-х гг. XIX century. статью об индийской живописи, указывал как на особенность индийской миниатюры на сильную примесь к акварельным краскам связывающих веществ, благодаря которым работа выходит похожей на живопись а tempera – прием, усвоенный художниками, быть может, ввиду знойности и влажности тропического воздуха Индии.

Изучить, какова была индийская миниатюра до Великого Могола Акбара, невозможно. Фишер даже предположил, что едва ли существуют миниатюры, которым было бы больше 200 лет. Относительно Акбара, отличавшегося веротерпимостью и покровительствовавшего всем искусствам и наукам, нам известно, что он заботился также и о живописи. При его дворе проживало более сотни знаменитых живописцев, и между ними, как указывают положительным образом письменные источники, было много персов, у которых учились молодые индийские живописцы. Самого знаменитого из этих художников, Дасванта, называют учеником ширазца Ширинкалама. Базаван как портретист был еще искуснее Дасванта.

Произведения индийской живописи сохранились тысячами не только в музеях Индии, но и во многих из европейских коллекций.

Mohammedan art in India, as well as everywhere on its borders, used borrowings from the art of neighboring areas. Originating from the ancient art of the Mediterranean coast, which, in turn, absorbed the ancient Mesopotamian influences, Islamic art everywhere on its way to the East met with ancient local traditions and brought its own into a mixture of Western and Eastern artistic elements.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)