The second main area of distribution of Mohammedan art covers the west of North Africa (Maghreb), Spain and some islands of the Mediterranean Sea. This is an area of Moorish art.

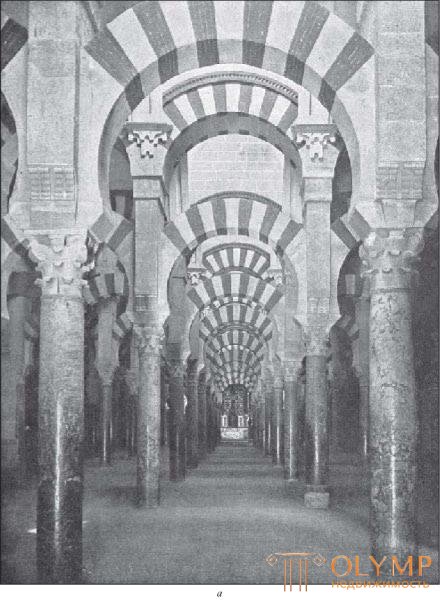

It is impossible to trace the development of Mohammedan architecture from its dependent embryos to the most magnificent and unique flowering anywhere else than in Spain. A large mosque, which began to build in Cordoba on the site of the old church of St.. Vikentiya Abdarrahman I in 786, initially had a plan for a real ancient mosque. On the side facing Mecca, in this case, in the south-east, to the front courtyard, surrounded by a series of arcades, there was a room with many columns arranged in 10 rows in the longitudinal direction (towards the prayer niche) and 12 rows in the transverse direction . This part of the mosque received extraordinary depth only in the 9th century, when all its naves, facing southeast, were lengthened through the addition of eight transverse aisles, and now it has become even more like a Christian 11-nave basilica, because the average longitudinal nave, contrary to custom, observed in Islamic architecture, was much wider than the others. The large front yard, the powerful columned hall, the dark, low main sanctuary, as Junggendel and Cornelius Gurlitt rightly pointed out, still resemble the structure of ancient Egyptian temples. But here as examples of what satisfies the needs of Islam, we must recognize only the oldest mosques of Medina and Egypt. In the X century. and this building, in which there were two hundred columns, could no longer accommodate all the faithful of a greatly expanded city. The mosque had to be increased again, and again from the southeast side, another 14 transverse aisles; then seven rows of columns and eight naves were added to it in the north-east side, so that now it consists, in addition to various extensions, of 19 longitudinal and 35 transversal naves. Monolithic columns of all kinds of rocks, numbering more than a thousand, placed inside the building, partly also in additional rooms and upper parts, almost all of Roman or Byzantine origin. They were discharged from Spain, France, and partly even from Constantinople. However, their capitals are mostly distorted imitations of antique specimens. Towards a prayer niche, the columns are connected to each other by horseshoe-shaped arches; in order to achieve greater height, the columns standing on the capitals of the columns and interconnected also by arches form the second tier of the backwaters; in the main points of the mosque, the upper pillars are decorated with semi-columns, and the arches are divided into smaller arches. Above this system, the head and arches ceiling in separate naves was originally flat, with beams not hidden from sight. Currently, most of the naves are covered with flat duct vaults. Due to its extreme stretch in width, a huge building seems very low, as if crushed, and its individual parts, with the exception of the richly decorated sanctuary, suffer from some nudity; but the whole forest of its columns with two rows of arches above them gives the impression of pomp and something fabulous, and the half-light reigning in the building leads to a visitor mystical thrill (Fig. 653, a ).

The finest of architectural works on the northern coast of Africa was the Marble Mosque in Kairouan, near Tunisia, a luxurious building erected during the restructuring of the Cordoba mosque to expand it (in 837). The roof of the Kairuan mosque is supported by four hundred ancient columns, forming 17 naves; in her prayer niche, ornaments of expensive burnt clay slabs alternate with openwork marble trim. The outer walls consist of layers of polished marble, alternately white and black. Details on Islamic art on the north coast of Africa are published by Ari Renan.

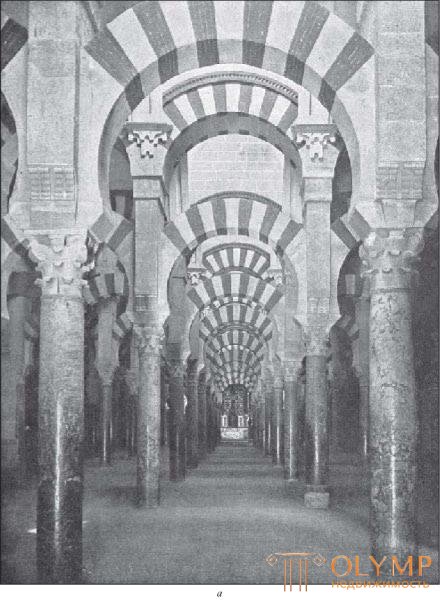

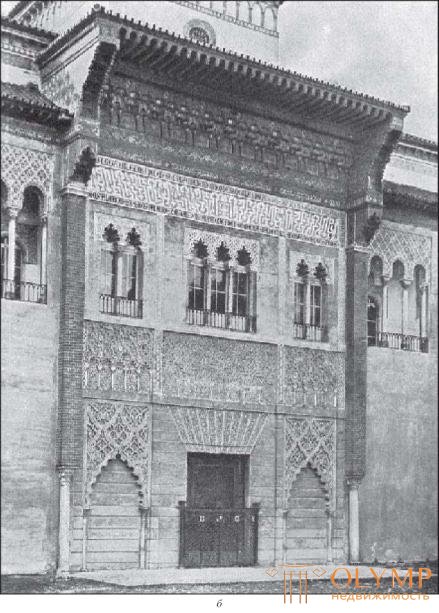

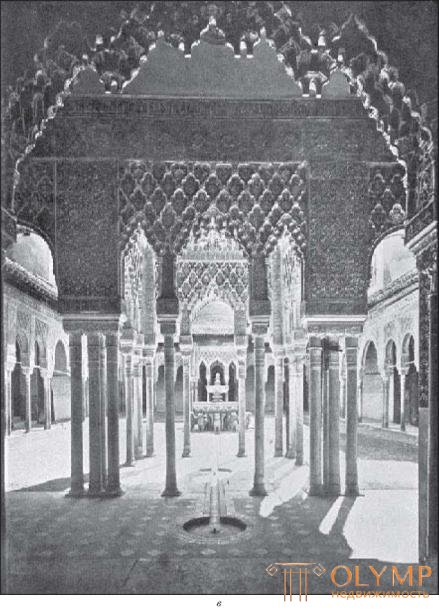

Fig. 653. Moorish architecture. a - interior of the Cordoba Grand Mosque; b - the main facade of the Seville Alcazar; c - Courtyard of the lions in the Alhambra; City Hall of the Court in the Alhambra. From photos of J. Laurent

Above the columns of the Alhambra, there are slender circular arches, very tall, as if standing on stilts, sometimes having a slightly horseshoe-shaped shape, sometimes stretched wide and flattened, less often pointed, but often dissected into smaller arches, the edges of which are filled with stalactites or sharp teeth. Slender marble monolith columns are equally often placed in pairs or singly; sometimes they are grouped even into three and four; they are always supported by arches. Despite the difference, albeit insignificant, of their forms, the original features of the Arabic-Moorish style vividly appear in them: there is a pasture ring above a simple base, several neck rings below the capitals, one below the other; the capitol serves as a flat calyx of leaves under a mowed-down cube covered with a rich sculpture, above which there is a kind of cornice that makes up the passage to the arch foot (see Fig. 639). The walls are clearly dissected on the base, the main surface and the frieze. The basement is almost everywhere faced with colored tiles (which here are called azulejos); the patterns are simple and majestic, the colors are gorgeous, but calm. The main field of the wall above the basement is covered with a patterned ornament, like a carpet, mostly cut from plaster and luxuriously painted; intricate linear pattern stretches like endless weaving, cut only by frames. On the friezes, as well as on the vertical stripes of the ornament between the arches or between the individual fields of the walls, fanciful letters of serious, humorous quotations from poets interlace with arabesques; in arabesques and here one can observe, along with strictly stylized floral curls, also taken from the real world, natural, although still slightly stylized plant forms. Ceilings shine with very bright, light colors; they generally consist of wooden stalactite arches, extremely varied and more or less complex, and in some places, such as in pavilions with a protruding roof, they are replaced by a wooden structure richly decorated and decorated.

The two main courtyards, around which are located the most luxurious halls and galleries, are called one Myrtle Courtyard, the other - the Lion Courtyard. Both belong to the second half of the fourteenth century. The courtyard of the myrtle is a rectangle 37 meters long and 23 meters wide. The middle of it is occupied by a long pool surrounded by myrtle. From each of the narrow sides of this courtyard, there are seven magnificent arches with beautiful upper galleries supported by six slender marble columns. The alcoves in the corners of these galleries are decorated with stalactite arches. From the gallery, which is located on the short north-eastern side of the courtyard, you enter primarily into a wide but shallow avant hall (Antisala de la barca), whose crown-shaped arch burned down in 1890, and from there, through a huge arch-shaped arch in the extremely thick wall of the tower Komares - in the Hall of Ambassadors, which occupies the entire quadrangular interior of this fortified tower, built in the first half of the XIV century. The walls of the tower are so thick that the embrasures of the windows made in them resemble small rooms. The hall covers an area of 11 square meters. meters It is two-tier in height, as can be seen from the two rows of its windows. It is covered with a magnificent stalactite arch. Among the patterns that have been repressed in the plaster facing of its walls, there are more than 150 individual motifs.

The courtyard of the lions (c), the construction of which was begun in 1377, is 28 meters long and 16 wide. It received its name from 12 black-marble lions supporting a wide lower bowl of the fountain, located in the middle of it, - figures that are plastic in their relation to coarse, but in architectural terms they are quite appropriate for their purpose. The courtyard is surrounded on all sides by an arcade gallery. The arches of its various widths either rely on single columns, now on pairs of columns, and in the corners even on groups of three columns. The walls above the arches and between them are covered with Moorish arabesques and quotation ornaments, which are here in all its splendor and splendor.

From each of the four sides of the Courtyard of the Lions, we enter one of the main halls of this part of the Alhambra; from the northwest short side is the entrance to the hall de los Mocarabes, a genus of the front, whose walls were originally covered with blue, red and gold ornaments and were crowned with a charming dome; the northeastern long side adjoins a hall with several floors above the courtyard with a floor consisting of two large marble slabs; the basement of this luxurious hall, known as the “Hall of the Two Sisters,” is lined with marvelous faience tiles, and the ceiling is a stalactite arch, remarkable in its size and taste of decoration; The doors of the cedar wood in this room, once gilded, are covered with luxurious carvings, and the plaster walls are delightful, intricately interwoven arabesques. "If you look at these amazing patterns," said Shaq, "in which the most unbridled fantasy is combined with deliberate calculation, then every minute it seems that all the combinations that you can think of are exhausted, and yet you see with amazement combinations grow newer and newer. " On the other long, south-western side of the Lions' Courtyard is the Abbensrarachov Hall, divided into three parts by two magnificent, wide toothed arches. The three-tiered middle part of the hall has a high stalactite ceiling, which represents transitions from a quad to an octagon, from an octagon to a hexagon, and, finally, from a hexagon to a circle. From the south-east short side of the courtyard is the entrance to the courtroom ( g ); with its stalactite arches and toothed arches, it gives the impression of a drop-type cave, crystallized rhythmically and symmetrically by a mania of magical forces.

Anyone who has ever been to the Alhambra will never forget the artistic impression received from her. It will seem to him that he is dreaming from “A Thousand and One Nights”, and yet everything is so clear, so clear, so comfortable that you feel a pleasant reality around you.

The artist's hands decorated the wall with tricky embroidery,

So think like flowers in front of your eyes;

The hall, all in elegant attire, youthful as a bride,

In the wondrous beauty of the marching procession going.

The magnificence of the Saracenic structures in Sicily is known to us only from the stories of ancient writers. The Norman Christians, having again taken possession of this whole island in 1090, first destroyed most of the palaces and mosques of the Moorish overlords, but soon after that they began to accept Saracen artists for their service. To the number of buildings erected here in the XII century. the Normans in the Arabic style with the help of the Saracens, owned two small entertainment castle - La Zisa and La Cuba, near Palermo. From the interior of their stalactites, faience tiles and marble mosaic preserved only a little. Their external walls are divided horizontally into tiers, and in the vertical direction they are enlivened with false arches and blind windows. The pavilion of Cuba located somewhat aside (fig. 654) is a special, fully completed whole.

Fig. 654. Pavilion of Cuba, near Palermo. With photos Talalyaritsy

The shape of the pointed arch in this Sicilian architecture indicates its connection with the Egyptian-Arabic.

В Испании после изгнания из нее мавров христианские государи продолжали пользоваться услугами мавританских мастеров при сооружении зданий в арабском вкусе; стиль этих христианско-мавританских построек принято называть мудехарским. Как на образцы этого стиля XIII и XIV столетий можно указать на две синагоги в Толедо, обращенные в христианские церкви Санта-Мариа ла Бланка и Эль Трансито. Санта-Мария ла Бланка, старейшее из этих двух зданий, – пятинефное сооружение с плоским покрытием и 28 подковообразными арками, опирающимися на восьмигранные столбы, увенчанные замечательными капителями в виде сосновых веток и шишек (рис. 655). Эль Трансито- single-nave building, it is distinguished by the history of the woods, it is decorated with ivory inlay. The so-called House of Seville is a building of the XVI century. The colors of the walls of the palace are lined up.

Of course, the art of craft and the industries of the world of Spain and Sicily .

Fig. 655. Hall of Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo. From the photo of J. Laurent

The main place of manufacture of silk fabrics in the IX-XII centuries. was considered the city of Palermo. After the conquest of Sicily, the Norman kings retained looms and Saracen weavers; Arabic inscriptions on Palermo silk fabrics of the XII century. indicate that the Saracen production of such materials was famous in the Christian world of this time. In Palermo, silk fabrics were often made even for the robes of the German emperors. The coronation cloak of 1132, located in the Vienna Museum, is decorated with images of symmetrical groups of lions, their backs to one another and separated from each other by palm trees; lions tear a camel apart; the pattern design is beautiful and lively in general, but in its details some refinement is noticed. The silk fabric of the imperial mantle of Henry VI, stored in Regensburg, is marked with the name of the Sicilian Arab Abdul Aziz. However, as Rigl noted, the Saracen works of this kind in the 12th century differed from the Byzantine ones only in their inscriptions and in part symbolic images weaved on them; otherwise, we see interrupted plexuses of lines on them, patterns of curls and leaves, and animal figures arranged in pairs, which, in any case, were not invented by Arabs for Mohammedan art.

Moorish faience production flourished mainly in Spain. Earthenware vessels, formerly considered Arabic-Sicilian (see Fig. 652), are now recognized as Syrian-Egyptian products of the XIII and XIV centuries. The importance that was previously attached to the island of Mallorca, on whose behalf the Italians called faience majolica, now comes down to the fact that Mallorca is recognized only as a place of sending Spanish goods to Italy. Whether pottery houses existed on Majorca itself remains unproved.

The art of the Ottoman Turks also began in Asia Minor. Their main cities, Bursa, Nikaia and others, under the sultans of the XIV century, especially when Murad I (1360-1380), who loved to work in buildings, were filled with palaces and mosques. The influence of Byzantine art was reflected in these buildings even more than in the Seljuk. A portal with columns of Corinthian character, but carrying stalactite capitals, leads through a narrow cross-hall to the main, domed building of the Green Mosque in Nicaea, named after its minaret, decorated with green plates. The Murad Grand Mosque in Bursa consists of a quadrangular room with pillars, a pool of water in the middle under the open sky and a small dome over each of the square spaces between the pillars. The small mosque of Murad in Bursa, in its four square domed portions of the naves, is very close to Byzantine Christian buildings. Prayer niches and some other parts of the Green Mosque and the Green Turba in Bursa, built at the beginning of the 13th century, are decorated with a tile with a tin green glaze.

Turkish architecture finally adopted the Byzantine character after the Turks took Constantinople in 1453 and made it the capital of their empire. Temple of sv. Sofia - a miracle of Byzantine art, turned into a mosque, became the only and unmatched model for all mosques, the construction of which was undertaken in Constantinople. Now Greek masters worked in the service of the Mohammedan architects. But, having adopted the Byzantine form of the central dome structures, the mosques did not abandon the front courtyards necessary for them; lancet arch, dominated in the XIV century. both in Cairo and in Bursa, it sometimes appeared in Constantinople; slender minarets, thin and elegant, began to rise high near the flat domes; Inside the mosques, the Christian mosaic was replaced by Islamic ornaments, playful in particular, and producing a strong impression in their entirety. In the mosque at the tomb of Ayub, built in Constantinople by Magomet II in 1458, the vast dome rests on four pillars. But there was no mention of any step forward in art. The Turks took columns and other architectural parts without long reasoning from Christian buildings, destroying them for this purpose. The mosque of Sultan Bayazet, built in 1498, is decorated with foreign columns of Egyptian granite, jasper and verde-antico. However, the famous mosque Suleiman II (1520-1566), the product of the architect Sinan, even after the temple of St.. Sofia gives the impression of novelty and beauty with the clarity of her proportions and a high dome, through the windows of which a mass of light pours inside the building; on the contrary, the huge marble mosque of Ahmed , which was completed in 1614 and was supposed to surpass the temple of Sts. Sophia, not only in size, but also in luxury, with her heavy crown of round columns, gives the impression of nothing more than imitation, and, moreover, unsuccessful.

The true autonomy is distinguished by the architecture of Turkish mosques only where it is used as a main decoration by a semi-faience tile, which, although it was invented in Persia, was widely used, as Otto von Falke proved, only in Turkey. In addition to the arabesques already known to us and the Persian antennae, which we still have to talk about, the main role in the ornamentation of Turkish faience is played, like national additions, by flat stylized stems with flowers of plants, especially carnations, tulips and wild hyacinth. One of the distinguishing features of these ornaments is the abundance of colors. Their background is usually white; the space enclosed in dark-gray contours is filled with cobalt blue, turquoise paint, green pendants and a bright red bolus, which is already a Turkish innovation. Occasionally the background itself is colored; in this case, the pattern is sometimes painted in white. The rectangular fields of the walls are often decorated with images of vases with bouquets of flowers mixed up with antennae.

Fig. 656. Turkish faience plate. By O. Von Falke

Turkish painted earthenware , round dishes and plates (fig. 656), flowerpots and jars with long necks were once considered Persian, then Rhodes was called their place of origin; it is now known that although Rhodes existed pottery production of this kind, however, precious semi-earthenware vessels with beautiful floral patterns, recognized by Otto von Falke as the most spectacular and exemplary ceramics of all countries and of all times, in fact stood out throughout the Turkish empire, and in Damascus bright red paint replaced delicate lilac. Plates with the same patterns, the same color and the same technology indicate the origin of the same tableware, the examples of which are particularly rich in the large London and Paris collections, but which are also found in Germany, for example, in Nuremberg, Dusseldorf and Dresden art-industrial museums .

If we recognize tiles and vessels, which we have just talked about, Turkish products, then fabrics with similar Turkish floral patterns, especially the brocade and velvet of the 16th century, as well as antique carpets for such worshipers, which are covered with such patterns, should be considered Turkish products; In particular, the patterns with flowers of carnations, tulips and hyacinths, wherever we meet them, are for us a sign of the Turkish origin of the subject.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)