1. Overview of the development of Spanish painting

A special feature of Spanish painting of the period was the combination of Christian motifs with careful detailing of everyday scenes, including from the life of the common people. In the transition from the Italian tradition to the national art, El Greco (Domenico Teotokopuli) was one of the most prominent artists of Spain.

Transition time

In the 17th century, the Iberian Peninsula moved into the first row of European countries with its painting, which represented mainly ecclesiastical or court art. And indeed, Velázquez, the greatest of the Spanish masters, is now generally considered the greatest painter in the true sense of the word.

The church still demanded mostly religious images, faithfully executed in accordance with the well-known rules set forth in the Pacheco book, the observance of which was monitored by censorship; the spiritual deepening was not put, however, no obstacles. The court demanded mainly portraits, in the case of historical paintings from the recent past of Spain, to which the connection with portrait groups gave strength and vitality; to decorate the castles, in addition, mythological allegories for decorative paintings, which were performed in the 16th century by visiting Italian craftsmen, were also required. In the hands of the great Spaniards of the new national direction, such works, preserved in small numbers, received a new, peculiar imprint. It was the great Spanish masters themselves who willingly wrote life-size genre paintings from the life of the people, in which they developed a characteristic sense of reality, but only as sketches for religious paintings and portrait works, and on occasion even landscapes that represented the guiding signs of a new understanding of nature, despite the entire decorative appearance of such medium-sized landscapes. Direct contact with earthly reality and with heavenly majesty gives the high technically Spanish painting of the 17th century a special charm.

Old information about Spanish paintings by such authors as Pacheco, Palomino, Vincencio Carducho, Giusepe Martinez and Ponz, are collected and replenished in the lexicon of the artists of Leon Bermudets in 1800. Among the newest Spanish researchers, Kruzada Villaamil, Tsarco del Valle and Jose M. Asentio are more important than others. In England, Sir William Sterling, in France, Blanc, Viardot and Lefort rendered services for the study of the history of Spanish painting. In German science, the works of Passavan, Vahagen, Luke still deserve attention, and Carl Justy investigated and assessed almost the whole area on his own.

The transition movement in Toledo, where the above-mentioned Cretan Greek Domenico Theotokopuli, El Greco (circa 1548–1614), a pupil of the aging Titian in Venice, settled in 1575 significantly manifested itself. This “Greek”, to which Kossio devoted two volumes in his Venetian works in 1908, stands next to Tintoretto, which is shown by his paintings “Healing the Blind” in Parma and Dresden and the portraits of Clovio in Naples. In Toledo, he gradually developed his fast, wily brush in connection with the widespread writing of aging Titian and the mature Tintoretto style and independently came to contemplative creativity, preferring elongated, thin, undoubtedly mannered forms and cool gray tone of colors, making him a bold innovator in in some cases, the predecessor of Velázquez, and in the eyes of the newest researchers and the father of modern impressionism. We are not at all surprised, therefore, that Meyer-Grafe puts him above Velázquez, but we cannot share his exaggerated assessment of this gifted master. His famous "Removal from the Savior of clothes on Calvary", "el Espolio" in 1579, in the Toledo cathedral is still at the stage of transition to the ghostly style of his late years. With a plea looking to heaven, the Savior stands in a red cloak between the executioners. The composition sees traces of the Byzantine-Greek receptions. More contemplative is already the mood in the "Trinity" in the Prado Museum. Part of the earliest, part of the more recent time are his numerous portraits in Madrid and Toledo, whose peculiarly inspired heads with long noses represent common types rather than portraits, sometimes even give the impression of majestic shadows of the other world. The best pictures of his new direction, marked by a triple gray-blue-yellow colorful chord, are wrapped in exaggeratedly long, often covered with a jerky movement, figures “The Burials of Count Orgatsi” (circa 1584) in Santo Tome in Toledo, “St. Mauritius ”(circa 1584) and“ Vision of Philip II ”(circa 1597) in the Escorial. The three main works of El Greco, completed in 1599 for the chapel of St. Joseph in Toledo, sv. Joseph, sv. Martin and Madonna with the saints represent the already fully developed language of his exaggeratedly elongated forms and a monumental composition. Of the paintings in the Prado Museum, the convulsive images of the Baptism of Christ, Crucifixion and Resurrection date back to the end of the 16th century, but the inspired images of The Descent of the Holy Spirit and St. Francis "show what he came to in the new century. It was his peculiar excessive excitement that made him the darling of the fashion of the 20th century.

Fig. 134. Crucifixion in Prado of Madrid by Theotokopuli el Greco. From the photo of F. Ganfshtengl in Munich

Of El Greco's disciples, no one followed in the footsteps of his super-artifice. Pedro Orrente, “Spanish Bassano”, who died in Toledo in 1644, who worked and created a school in Valencia, joined his early paintings in the Cathedral of Toledo (“Adoration of the Magi”, “Adoration of the Shepherds”, “St. Ildefonso”) , to the Venetian youthful style of his teacher, and later, as a zealous observer of the animal world, he moved on to an independent kind of portrayal of animal groups and landscape distances in the spirit of “bassans”. Numerous paintings of him are in Madrid. Characterized by his "Meeting of Jacob with Rachel" in Dresden. Of the eight paintings in the Prado Museum, some are completely devoid of biblical episodes for the sake of clean landscapes with shepherds and herds. Fresh on observation, juicy and colorfully written, they enrich the field of themes and understanding of nature in Spanish painting. On the contrary, the disciple of Theotokopouli, Juan Bautista Mino (1569–1649), developed a transitional style, peppy in shape and color, which, as the Adoration of the Magi in Madrid shows, sometimes resembles the pale yellow tone of Caravaggio’s early years; and Louis Tristan (1586–1640), the most often mentioned student of Greco, whose best works are the great altars of the parish church in Iepes and Santa Clara in Toledo, sometimes even approaches the art of Ribera with its confident shapes and depth of colors, dark shadows and bright light spots .

2. Leading schools of Spanish painting

The leading role in the development of Spanish painting was played by the Valencian, Madrid and Seville schools. Since the first two maintained stronger ties with Italian and Flemish art, it was in the Seville school that national styles were formed before.

Valencia

In Valencia, to which artists Alkagali dedicated a not entirely successful critical lexicon, followed by Juanes, was followed by Francisco Ribalta (circa 1555–1628), a strong leader in transition art of the 17th century. Ribalta made good use of his school years in Italy. It is possible that he studied Correggio in Parma. Returning to Valencia, he nevertheless appeared in his numerous paintings as a master who, as I wrote several years ago in Valencia, “represents Spanish art at the point of its transition to independence, is already quite a colorist in the sense of unity of tone and magical light and shade and besides, he can combine very confident forms and angles with personal originality ”. Flaming faith he animates his life Spanish types. On their knees, the apostles are crowded around the table at his illustrious "Last Supper" in the Collegium del Patriarque in Valencia (1605). A stunning impression is made by the “Position in the coffin” of his magnificent sacred altar of the same church. Inner spirituality and freedom of execution is different “St. Bruno ”in the Valencia Museum, where there are a number of other works by Ribalt, revealing the almost mature power of the new Spanish painting.

The oldest of the truly great, completely free Spanish masters of the new century remains a student of Ribalta, Giuseppe de Ribera, who we enrolled at the Neapolitan school, although he was Spaniard from head to toe. We cannot dwell on the other students of Francisco de Ribalt, not even on his son Juan (1597–1628), but mention that under the leadership of Pedro Orrente, the battleist Esteban March (about 1598–1660) formed in Valencia. “Crossing the sea” reveals his light, fresh, but not yet unconventional manner to depict mass movements.

Madrid

The glorious school of Madrid, described in the general works of Beruete and Moreta, was essentially influenced by the invited courtyard of Italian artists and 16th century Italian paintings bought for palaces of the 16th century, when Velazquez was its guiding star in 1623. Later, the influence of the Netherlands, Rubens, who visited the Spanish court in 1604 and 1628, and Van Dyck, who sent his paintings to Spain, affected. The Madrid pupils of visiting Italians, without revealing clearly expressed autonomy, following the passage of time, proceeded, however, gradually to a freer pattern, to a wider letter and to a more coherent and expressive tone, but often to a weaker color, Vicencio (Vincenzo) Carducho (1585 –1638), a disciple of his brother Bartolome, who also visited Ribalt’s workshop in Valencia, stood at the head of these masters. The largest of his works were 55 paintings from the life of the Cartesians in the Cartesian monastery of Paular. The most important of them hang in the premises of the former Trinidad Museum in Madrid. The Prado Museum has twelve paintings of his brush. “Vision of sv. Gonzago ”(1630) in Dresden is characteristic of his more advanced late manners, essentially realistic, but with a gentle tone, contrary to his own dialogues (“ discursos ”).

Italians, like Carducho, were born by Eugenio Cacses (1577–1642) and Felix Castello (1602–1652), a student of Carducho, who also gradually made steps towards the new national art. A gifted, truth-seeking student of Carducho, José Leonardo (1616–1651), ending the transitional period, was, however, a Spaniard.

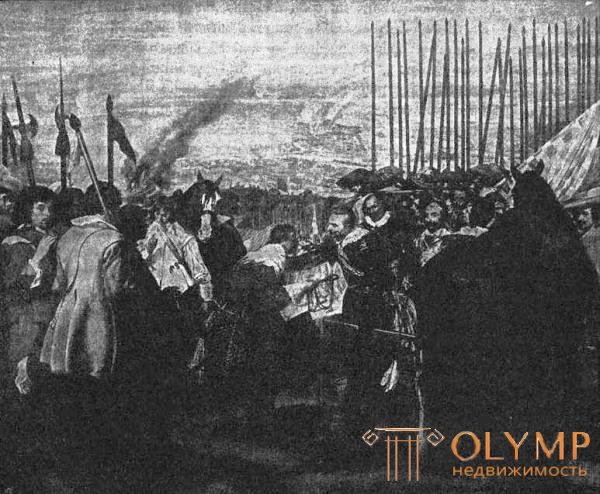

All these masters participated in the original art enterprise of the Madrid court yard, the implementation of which, except for Juan Bautista Maino, was headed by the great Velázquez. Mino chose scenes, artists Velasquez. It was about decorating the royal hall of the Buen Retiro castle with twelve paintings of modern life, representing the Spanish wars, i.e., a completely modern task, solved with more realism than similar tasks in the French court. Eight paintings are preserved in the Madrid Museum. Of these, Minot belongs to "Allegory of the Conquest of Flanders", Vicencio Carducho - "Battle of Fleurus", "Liberation of the City of Constanza" and "Siege of Reinfels"; Eygenio Kakses - “Liberation of Cadix”; Felix Castello - "The victories of the Spaniards over the Dutch" and "The landing of General Fadrikva in San Salvador", Leonardo - the magnificent "Surrender of Breda" and "The capture of Akvi." In these pictures, the main role is played by the victorious commanders - everything is in the foreground, the battle is mostly seething in the background. General reception tends to produce a picturesque effect. But if you compare all these paintings with similar works of Velázquez, not yet mentioned, it becomes obvious that they are still on the eve of the sanctuary of Spanish national art.

Seville

Since the great master of Valencia Ribera moved to Naples, it is an honor to be the birthplace of the new Spanish national style behind Seville, the painting of which was described by Centenach. Of the rough, cold, still Italianizing masters of transitional time, Juan del Castillo (1584–1640) deserves mention — and only as a teacher of Kano and Murillo — and Francisco Pacheco (1571–1654), as well as the teacher and father-in-law of Velasquez, with one hand, and the author of the "Book of Painting" - on the other. Inside the new movement they followed the “old direction”. A strong artistic revolution was accomplished in the works of Juan de las Roelas (circa 1558–1625), a native of the Netherlands, but probably having completed school in Italy. Although Flemish and Italian memories are found in his style, he nevertheless reworked them into a peculiar Spanish style of sharp characteristics, flowery colors and radiant lighting effects. His early paintings belong to the great "Crucifixion of St.. Andrew "in the Seville Museum, with sharply defined types, fiery, still variegated, but rich in play of colors and a bluish-green landscape. "Conception" in Dresden, with the Virgin Mary in blue on top of a red dress, is still not free enough. His best works are already quite on the other side of the transitional movement. This is the magnificent “Battle of Klovigo” with a radiant Jacob on a white horse (1609) in the cathedral of Sangra, a bright “Trinity Day” in the Sangre hospital and flooded with light, realistically conveyed “Death of St. Isidro "in the church of this saint in Seville.

At the head of the ripening Seville school of the 17th century, the first teacher of Velasquez, Herrer el Vieyo (1576–1656), who studied with Pacheco under a certain Luis Fernandez, was put. Herrera is considered the first independent naturalist and painter of a wide scope of the Spanish school. Without a doubt, with his bold, juicy brush he sought new power and greatness; but his strength has not yet leveled, his language of form is often harsh, and the lighting effects are exquisite. “The Last Judgment” in San Bernardo in Seville, whose “sinful souls” made an impression in Spain simply because their nakedness is really naked, yet still reminds of Roelas, whose influence is undoubtedly. His “Trinity Day” in 1617, seen by us in the Lopez Sepero Gallery in Seville, with colossal figures in the foreground depicting “Acute Words”, is indeed a revelation in comparison with the picture of the same Roelas content; "The triumph of sv. Hermengilda ”(1624), the Visigothic saint in a blue steel armor, ascending to heaven in a round dance of sparkling gold angels, is already unfolding all the means of his turbulent art. Of his genre paintings of the tavern life of the people (bodegones, bodegoncellos), which had, perhaps, the strongest influence on Velasquez, not a single reliable one remained. In general, he certainly stands on the basis of the new century.

His son Francisco Herrera El Mozo (1622 to 1685), who visited Italy, and then, like his father, who moved to Madrid, was more gentle, flexible and pleasant. His "St. Hermengild "in Prado bends and bends according to all the rules of baroque painting.

For the first time, the naturalistic Spanish style of the era reaches the fiery, courageously strong, but conscious stability of Roelas disciple Francisco Zurbaran (1598–1662), who knew how to faithfully convey the nature that served as a model for every image, every head, every dress, with the highest power of religious animation. Appointment of art Zurbaran saw mainly in the image of the monastic to the legends of visions. At the same time, he was not only a good draftsman who managed spatial relationships, but also a born painter, who, with some dryness of writing, combined in one tone few, but strong local colors with black, white and gray and filled them with a stream of bright light. In short, Zurbaran after Ribera, who had no influence on him, is the oldest mature Spanish painter of the new era. Already in the altarpiece of Seville Cathedral (1625), he stands on the path to independence. In "Celebration of sv. Thomas Aquinas ”, located in the Seville Museum, is already quite distinctive, with its fascinating characteristics of faces and a clear brilliance of lighting. Two series of his paintings from the monastic life, written in 1629 for the Seville monasteries, the most sustained and mature works of this master in drawing and color. Pictures from the life of St. Pedro Nolasco got part in the Madrid Museum, from the life of St.. Bonaventures are divided between the Louvre, Berlin and Dresden galleries.

Fig. 135. “St. Bonaventure ”, painting by Francisco Zurbaran in the Royal Dresden Gallery. By photography ed. F. Brookman in Munich

The rest of the famous masters of the Seville school came from the workshops of Pacheco and Castillo. Alonso Cano (1601–1667), already known to us as an architect and sculptor, became a painter and traded Pacheco’s workshop to Castillo’s workshop. He worked one time in Madrid, but in the end Granada returned. He owes his main success to painting. Although the shadow of the old school is felt behind his calm, rounded pattern and carefully selected colors, thanks to the animation and power of his imagination and the gentle smoothness of his brush, he achieved the freedom of the new national Spanish art. В мадридском музее Прадо, где находятся его произведения «Тело Христа, поддерживаемое ангелами», «Христос у колонны» и прекрасная, сидящая среди ландшафта Мадонна со звездами в ореоле, он лучше представлен, чем в музеях Севильи и Гранады. Его сильнейшую сторону подчеркивает чисто андалузская черноглазая св. Агнеса в Берлине, а более слабым образцом его искусства является св. Павел в Дрездене. Высшую ступень его искусства показывают «Распятие» мадридской академии и Мадонна Севильского собора, а шедевром его, особенно счастливо соединяющим теплую задушевную жизнь, чувство красоты и искренность, нам представляется «Мадонна дель Розарио» в соборе города Малаги. В общем, Кано намереннее, чувствительнее и слабее, чем Рибера, Сурбанат и Веласкес. Благодаря ему испанская живопись не стала бы мировым искусством.

Fig. 136. «Мадонна со звездами» кисти Алонсо Кано, в мадридском Прадо. From the photo of F. Ganfshtengl in Munich

Земляк и младший товарищ Кано по мастерской Кастильо, Педро де Мойа из Гранады (1610–1666), представляет особенное явление в испанской художественной жизни этого века, в том смысле, что вместо Италии он побывал в Нидерландах. В Лондоне он, вероятно, был до 1641 г. учеником ван Дейка, а позднее, в Севилье, повлиял на Мурильо в духе этого мастера. К сожалению, нет достоверных произведений, которые подтверждали бы наглядно эти отношения. Главным произведением Мойа считается интересный запрестольный образ в гражданском соборе, представляющий Марию с мальчиком Иисусом в облаках над коленопреклоненным епископом.

3. Реализм Веласкеса

He was the one of the most prominent of the seventeenth century. In his works, he developed his own method of transmission.

In the works of the great seviltsa Diego Rodriguez de Silva and Velázquez (1599–1660) with greater clarity than in the works of any other painter, not excluding the Dutch, it was found that in the fine arts of the XVII century, along with the electro-baroque trend flourished realistic natural, foreshadowing the nineteenth century. From realism in the sense of Caravaggio or Ribera, independently reworked in connection with the direction of his first teacher, Herrera, Velázquez quickly rose to an independent style of painting, immediately convincing and old and small with the direct experience of nature, passing through the free painting of an aging Titian, whose work is an equestrian portrait Charles V - he met in Madrid, through the powerful Tintoretto's total painting, “Crucifixion” and “The Last Supper” which he copied in Venice, through a peculiar, cold, abundant sulfur Risto-gray tones of the main colorful language of El Greco in Toledo nearby, its antipode in almost all other respects. Having taken as a model a careful painting technique that is hard on paints, having gone through all the phases of broad, smooth writing, he finally achieved that bold, free application of paints, which in the landscape and in clothes earlier than in the heads and hands merges only in the viewer's eye individual brush strokes in a naturally glowing surface. From the warm color with dark shadows and one-sidedly incident light, he gradually moved to that calm, clear, pure distribution of daylight, gently appealing to his figure, which was joined by modern painting "full air". From a simple transfer of nature, he gradually moved, always remaining a keen observer-realist, to the nobility of artistic experience, which gave him the opportunity even for repulsive nature to lift over the bare reality into the sanctuary of artistic truth and beauty.

There is no artist, to such a degree free from mannerism, as Velázquez. It seems that nature itself would have to write like it, if it had taken it into its head to throw its manifestations on the plane in the form of images. Already Raphael Mengs said in the XVIII century about one of his paintings, that it was written “by will alone”. V. Bourget celebrated it in the middle of the XIX century as “the painter of painters” (“Le peintre le plus peintre”).

Solid separate essays on Velasquez began in 1855 with Stirling's book; Lefort followed in 1800, Curtis in 1883. The self-developed work of Karl Yusti about this artist appeared in 1888, the second edition in 1904. Meanwhile, the works of Michael, Armstrong, Romanos, Stevenson and in particular Beruete made many new views and points of view.

Changes in the style of Velázquez cannot be timed to specific years. Yet the course of his artistic development is most clearly divided by his travels. After the first artistic trip from Seville to Madrid, in 1622, Philip IV in 1623 invited him once and for all to his capital and residence, and in the service of this monarch, an art lover, having reached the influential and responsible position of the palace marshal, he remained for the rest of your life. This service was interrupted only by his two trips to Italy, 1629–1631 and 1649–1651. The names of Philip IV and Velasquez are inseparable.

The work performed by Velasquez in Seville before 1623, “The Adoration of the Magi” in 1619 in the Prado Museum, is a tall picture, light in composition and expressive, with dark shadows and sharply falling light streams from the left, only with a superficial glance reminiscent of Ribera, and Each stroke of the brush is Spanish. Then especially characteristic for the first period of his work "Tavern and kitchen scenes", in which he fastened folk figures, life-size, in their daily lives. The sharp, one-sided overhead illumination of these paintings is explained by the high-spaced windows of the basement floors, in which these unsophisticated scenes are played out. But the great life truth and the spontaneous movements of the depicted figures are explained by direct observation of nature by the master.

Like Pacheco, he took to his residence a young guy who served him in kind. The everyday situation of these paintings is strikingly natural, but it is predominant in the sense of a general impression. The main pictures of this genus are “The Old Cook” in the Cook collection in Richmond, “The Boys Lunch at the Kitchen Table” and “The Drinking Boys at the Water Seller” in London. The transition to religious paintings is a picture of the kitchen of the London National Gallery with Christ, Martha and Maria in the back room. A confidently modeled male bust portrait (No. 1103) in the Prado Museum in Madrid has survived from this early Seville era.

The Prado Museum also owns the first Madrid portraits of Velasquez, a breast portrait of a blond 18-year-old king and a portrait of him full-length in a new black full dress, beside the table covered with a red tablecloth. The "similarity" of this portrait and the calm dignity of posture delighted the courtyard. The gray background has not yet been developed prospectively. The shadow of the king falls into the void. This is also followed by the full-length figures of the omnipotent minister, Count Olivares, now at Dorchester House in London, and the third early portrait of Infante Carlos in stature, standing in a free, artlessly cleverly grasped pose, holding the left one, wearing a glove, hand hat, and the right glove removed. These pictures are adjoined by a more successful in composition expressive half-length portrait of a young man in Munich.

The middle between the portrait and the genre picture is taken by the remarkable, peculiar figure of the “geographer” in the yellow mantle in the Rouen Museum. From folk scenes resembling life-size group portraits to mythology, the final for this period of creativity is the picture of his "Drunkard" or "Bacchus crowning Drunkards" in Prado. The naked god, wearing a wreath, sits on a barrel, behind him lies his satyr. Seven dressed cheerful drinkers from the common people are all around him, sitting on their knees and squatting. Rubens, the painter of the Bacchus rampage, was at that time in Madrid. Velázquez probably wanted to riot him in his area. One cannot look without a smile at this precious, enthusiastic picture, standing in the same relation to specially mythological paintings as Ganymede Rembrandt. Separate figures still belong strictly to themselves and are distinguished by rounded plastic modeling. But the warm golden tone already binds them together. All light and colorful means for individualization and general artistic unity are skillfully put into play. Not only in Spanish, but also in world art this picture stands alone.

One cannot agree that the “historical paintings” written by Velasquez in Rome in 1630 suffer from Italian Baroque, as they asserted recently. Greater fame than the "Clothing of Joseph" in the Escorial, is enjoyed by the "Volcano Forge" in the Prado Museum, as is the "Bacchus" belonging to mythological subjects. A mythological forge with five slender, wiry, surprisingly modeled workers, only in one aprons, among which God himself does not stand out with his conditional beauty, could pass for the usual Spanish forge. On the left stands the god of light, crowned with laurels and surrounded by a bright halo, is also not a traditional, but a genuine human image. He eagerly tells something. The dumbfoundedness with which everyone, interrupting work, listens to him is transmitted amazingly. The subtlety of the image of the transitions of light from different sources - from the blacksmith's forge and the luminous god - Velázquez has surpassed all previous attempts of this kind.

New revelations were also two landscape etudes of the Roman villa Medici. Never before has nobody seized the landscape like in these fresh, bold and widely located, filled and imbued with light and air, garden landscapes. It was these sketches that prepared the later paintings by Velasquez with figures against the background of the landscape, illuminated by real light. The first attempts of such a transmission are discovered by the bust portrait of the young Hungarian queen, already written in 1630 in Naples, in the Madrid Museum (No. 1072).

In the next eighteen years after his return to Madrid, Velasquez devoted himself mainly to portrait painting. Two expressive religious paintings nevertheless belong to this period (1631–649), namely, the touching “Christ at the column”, with the plaintively prayed child, led by an angel, in the London gallery, a picture with a warm tone, plastic modeling, is extremely peculiar masterpiece, and then “Christ on the Cross” in the Prado Museum, in the medieval spirit, with separate feet nailed by Pacheco’s order, dark strands of hair falling from the crown of thorns to the right side of the face, with an expression of deep calm after ourselves to fight: a grand, calm, holy picture.

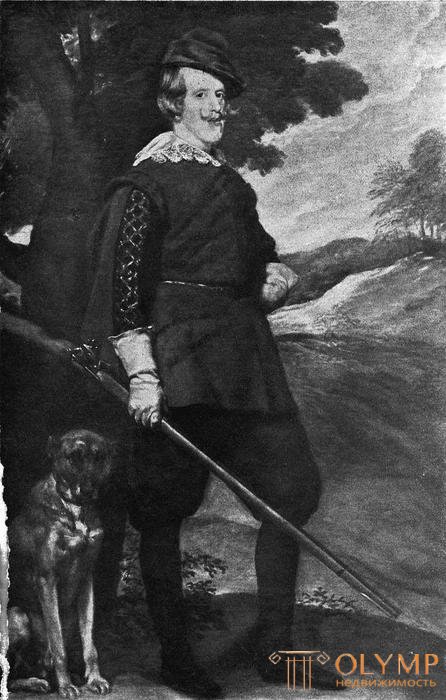

At the head of the court portraits of Velasquez belonging to this era, there are three excellent hunting figures in the Prado Museum: King Philip, Cardinal Infant Ferdinand and little Infant Don Balthasar, depicted outdoors, with guns in their hands and with dogs, as well as three magnificent equestrian portraits: King, Duke of Olivares and Infante Balthazar, on horseback, in front of the vast landscape of Guadarrama. These six famous paintings breathe all the charms of mature perception and painting of the master, but still retain the conventionality of landscape light. The great painter of people and monarchs is one of the greatest painters of horses and dogs in the history of art.

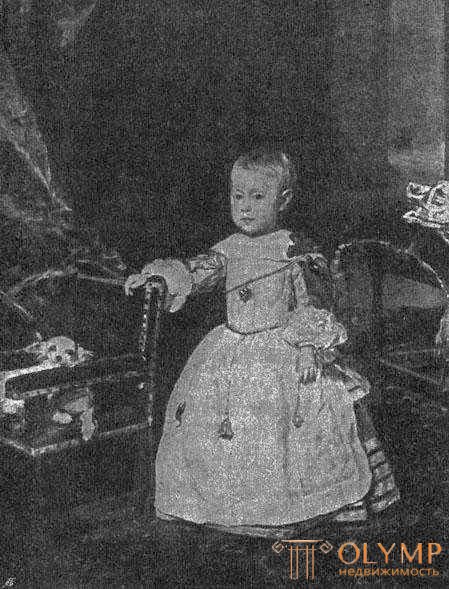

Fig. 137. "Infant Philip Prospero." Velasquez's painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. From the photo of F. Ganfshtengl in Munich

The London gallery is also full-length portrait of King Philip; the infante Don Carlos has a full-length portrait of Vienna; Adjacent to them is an amazing, colorful painting in the Museum of Art in Boston, with a striking sense of space and simplicity depicting the little Prince Balthazar with a court dwarf. The portraits of the royal family are followed by portraits of their antipodes and companions of court dwarfs and jesters, the inner being and the external, often ugly, images of which Velasquez could reproduce with an incorruptible love of truth, surrounding them, however, with a touch of humor. Around 1635, a portrait of a jester Pablillo appeared in Prado, standing with his legs apart, on a flat background. Ten years later, the portrait of the dwarf El Primo (ibid.), Sitting in front of an open mountain landscape, brightly lit, with a big black hat on his head appeared. The whole ten-year development of the master is reflected in the different performance of these two paintings.

Fig. 138. "Surrender Breda." Painting by Velázquez in the Prado, in Madrid. From the photo of F. Ganfshtengl in Munich

Of the lap and chest portraits of this period, we can note here only the magnificent, with fiery eyes, his self-portrait in the Roman Capitol meeting, an excellent portrait of Jagermeister Mateo in Dresden, portraits of Philip and Isabella in Vienna, Olivares in St. Petersburg. As Velázquez developed now curved etudes in the air, shows him “The Hunt for a Boar” (1638) in London. Everything is wonderfully subtly matched with a slightly cloudy blue sky; Numerous small figures are strikingly picturesquely distributed, filling the vast picture one by one, in groups and in crowds. Velasquez’s truly masterful work of this kind is the magnificent picture of Prado (1639–1641), depicting the surrender of the Dutch fortress Breda (1625) to the Spaniards. An older picture on the same topic by José Leonardo faded into the background. Here in the hands of such a master as Velázquez, the group portrait imperceptibly turns into a historical picture. No episode has ever been reproduced so easily as the transfer of the keys of a fortress by the Dutch commandant, the Spanish commander Spinole, depicted in the center of this picture. An amazing life is bursting with the Dutch soldiers standing to the left and the Spanish soldiers standing to the right, between which a wide, light-filled distance opens. 28 Spanish lances, which decried Mengs, fill the space and do not allow to run away. The picture with its deeply truthful, free, broad development foreshadows the last step in the development of the only Sevilian.

4. The Late Period of Velázquez

The late period in the work of Velázquez begins with a second visit to Rome, which continued to remain the leading cultural center of the region and a popular place for all European artists. His further work acquires ever greater expressiveness, refinement and mastery in the transmission of lighting. According to the last of these qualities, the works of Velázquez are on a par with the creations of the 19th century impressionists.

During Velasquez’s second time in Rome (1650), he painted only two excellent portraits: the expressive half-figure of his slave and the mulat's student Juan de Pareius, in Longford Castle, and the world-famous generational portrait of Pope Innocent X, leaning in the back of his chair, in the gallery of Doria. From the point of view of painting, this magnificent portrait convinces with the confidence of a fast, wide brush, from the point of view of color, it delights as a symphony of red, white and gray, and as a portrait it is a true miracle of a convincing transfer of a person’s body and soul.

The last nine years of this master's life (1651–1660) were also extremely fruitful, despite the troubles associated with the court office. the themes on which he wrote at that time are more varied than ever.

Both of his later religious paintings in the Prado Museum are cited as evidence of El Greco’s influence on the latter stage of his development. Agree, “Marriage of Mary”, convinces that Velasquez should have known the Greco painting of the same content in Toledo (San Jose Chapel), but he transformed it into his own work, making the more refined language of forms and hotter the cold consonance of three colors: red , blue and gray. Less obvious is the dependence of the landscape of his “Visit of the Hermit Paul by the Abbot Anthony” to the landscape of the painting by Theotokopouli “Francis y Zuloaga” in Paris. The landscape of Velázquez gives the impression of being more plastic and picturesque, more classical and at the same time more modern. Actually, this picture is a historical landscape, the charm of which lies in its free, light and nevertheless balanced composition in forms and in the abundance of clear light that illuminates the landscape with a dark blue, green and gray colorful consonance.

In the last period of his work Velasquez also was not spared from writing mythological decorative paintings for the royal castles. One of them, the stately “Resting Mars”, for which some mustached Spanish fellow did in kind, flaunted in Toppe de la Parade between famous, realistically painted from ancient images, ideal portraits of the ancient Greek philosopher poets Aesop and Menippe. All three belong to the Prado Museum. Four other mythological paintings filled the narrow rectangular fields of the mirrored hall of the Madrid Palace. Of these, only two survived: “Mercury and Argus” in Madrid, “Venus looking in the mirror” in the London gallery. The format required a recumbent position of the main persons. Wonderful Venus lies on its right side, with its back to the viewer; her head is reflected in the mirror that Cupid is holding in front of her. With a special art, her beautiful body is written in light tones. Doubts about the authenticity of this picture, we consider unfounded.

Fig. 139. "Philip IV in a hunting suit." Painting by Velasquez in the Prado in Madrid. From the photo of F. Ganfshtengl in Munich

Since then, portraits of monarchs and jesters have become more and more spiritual and noble expression, and according to the painting techniques they become easier, freer and more tender. Let's call it worthy

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)