1. General overview of the development of art

The beginning of the XVII century becomes for Spain the era of the birth of the first notable forms of national art. Thus, in architecture, baroque comes to replace the formerly strict classicism, which, although developing under the influence of Italy, still contains many purely Spanish features.

With the three kings who ruled Spain during the seventeenth century, Philip III (1598–1621), Philip IV (1621–1665), and Charles II (1665–1700), the world monarchy, in which the sun never set, gradually began to split. Not only the Dutch, but also Portuguese fellow tribesmen throw off the shackles of Spanish rule! The French assign, part by part, the Spanish possessions both in the north and in the south! But the Spanish land, after the expulsion of the Moors under Philip III and the suppression of the Catholic and Aragon uprising under Philip IV, became all the more spiritually closed up into a single whole, linked by the unity of faith enshrined in the Inquisition. In 1600, Calderon was born, the greatest Spanish playwright and the most ecclesiastical of the great playwrights. But already in 1605, Don Quixote of Cervantes, a masterpiece of Spanish folk writing, appeared, and the educational arts of Spain, which had previously been in contact, alternately or simultaneously, with the Gallic and Germanic north, with the Italian east and with the Moorish south, were already shown in early XVII centuries that they have learned to look with their own eyes and stand on their own feet. A century later, the autumn of Spanish world power became the spring of Spanish national art, which managed to merge closely the fiery churchliness with naive humanity.

Already in the 16th century and earlier, Spanish construction art, first in the “jewelry (plateresco) style” abundant in decorations, speaking about the wealth of Spanish fantasy, then in Herrera’s classical style, reflecting Spanish dignity and grandeur (grandezza), created works despite the processing of alien items worn national imprint. Therefore, in contrast to the visual arts, it is the Spanish architecture of the 17th century that does not detect at first an increase in national content. On the contrary, the classicism of the style of Guerrera, moving to more picturesque, fun and beautiful forms, gradually approached the Italian Baroque, and only at the transition to the XVIII century (even more among the followers of Hurrigvere than he himself) returned to the complexity and overload of the national jewelry style and even outdid it with a new mixture of forms. The purely Spanish features of the 17th century are the quadrangular corner towers on both sides of the church and secular facades, the Tuscan-Doric capitals of the columns with a wreath of leaves around the neck, and instead of or next to the motifs of the old "orders" - a new decorative motif consisting of "superimposed and hanging plates ”, in this case originating from the Mauritanian designs, rather than from the architecture of Wendel Ditterlin.

If until now the Spanish construction art of this era was the stepchild of our manuals, now it is vividly highlighted by the thorough work of Otto Schubert.

The best student and collaborator of Juan de Guerrera, Francisco de Mora, who died in Madrid in 1610, supplemented the work of his teacher with paintings of two chambers and the parish church in Escorial de Abayo, moreover, he did not go further than his closed severity due to his easy tasks.

New churches for sermons and processions, built by the Jesuits, are almost always the usual and, in Italian Jesuit churches, the shape of a Latin cross, located inside a rectangle with side chapels, over which empores stretch. Rarely there is no dome above the center of the cross, under which the main altar is sometimes placed, while the choir, surrounded by walls, has been placed in a longitudinal body in Spain since the ancient times, now, like in the rest of Europe, is transferred to the short eastern end of the cross to enhance the overall impression, and the altar also moves behind it.

A particularly strict building of this kind is the church of St.. Nicholas in Bari, in Alicante, granite building without decorations, in which the choir is still in the longitudinal nave, and the main altar is directly behind the transept. The considerable height, excessively long and thin Doric pilasters in height of both floors inside, the pointed upper floor and the fourteen-square-shaped chorus (1616–1637) also speak of Gothic memories. But the dome (about 1658) is decorated only with strict square "tapes".

It is instructive to compare the earlier facade of the small church in Nuestra Señora de las Angustias in Valladolid (1597–1606), performed by Juan de Nates, with the lush facade of Gaspard-Ordóñez, the Jesuit church in Alcala de Henares (1602–1625). Both facades are two-storey, Corinthian, with gables. But the first one almost does not detect baroque elements, its entablments are not even protruding above the columns, projecting three-quarters of the walls, the second one has already protruding entablaments, a forked arched flat pediment of the portal, window frames beveled inward, and mature-looking cartouches.

Colegio de donna Maria da Aragón in Madrid (1590–1599), the famous Greek-Venetian artist Domenico Teotokopuli (circa 1548–1614), who worked in Toledo, gave the first oval in Spanish soil in terms of plan, located across. The two-story facade is dissected by a composite order, the inside is eight semi-columns of free Ionic style. Further development of this plan is the Bernardine Church in Alcala de Henares (1618), usually attributed to the sculptor Juan Bautista Monegro. Four rectangular axes adjoin the main oval with gilded, baroque in their dome lines along rectangular axes and four oval chapels diagonally.

The cathedral extensions of Nicholas Vergara the Younger (1595–1616) in Toledo, namely rectangular sacrestia, square, with a flat dome of Capilla de la Virgen del Sagrario and octagonal, conical with arches the sacristy (“Ochavo”) with strict profiles are already distinguished by a large conglomeration of forms and their freer combination, reminiscent of Schubert's style of Galeazzo Alessi.

Yorge Manuel Theotokopouli, the son of El Greco, covered the Moorish southeastern chapel of the cathedral (1626–1631) with an elegant octagonal dome with thin ribs, slightly constricted at the bottom, reminiscent of the Moorish style.

The town halls of the Spanish cities, which arose mostly in the 17th century, also reflect the gradual transition from Herrere's rigor to greater freedom. The three-storey, with side towers, facade of the town hall in Segovia, with its Tuscan columns, located in front of the circular arcades of the lower floor, still remains essentially on the soil of Francisco de Mora. On the facade of the town hall in Reus, Juan Mas and Antonio Puyades built in 1601 (as it seems, for the first time in Spain) a gable with volutes with through cartouches of coats of arms. The magnificent two-story Town Hall in Toledo, built by the aforementioned Junior Theotokopuli in 1612–1618, with its domed side towers, a flat triangular middle pediment, a classic decoration of the lower floor by Tuscan, upper Ionian columns, still gives the impression of a purely high Renaissance, although some particular forms, such as window frames, are already touched by the baroque.

The last representative of classicism in the sense of Francisco de Mora was a native of Madrid, Fray Lorenzo de San Nicolas (1597 to 1679), who built in 1623–1624. Doric Church of San Plasido in Madrid, and in 1633, wrote an essay on the art of building.

2. Stages of development of Spanish Baroque

The process of improving the Baroque style and giving it national character is traced in the works of a number of prominent Spanish masters who worked in the 17th and early 18th centuries. A significant part of the characteristic examples of this style are the cathedrals and churches of major Spanish cultural centers.

Juan Gomez de Mora, Francisco's nephew, in whose hands the framing of the dismembered parts of the building really became sharper, complicated, became intertwined with each other, the forms mixed more freely, more tender and luxurious, the overall impression of the building became more luxurious and luxuriant. .

If its first building, the convent church La Encarnacion in Madrid (started in 1611), still fully preserves the style of his uncle, his best work, the Jesuit College in Salamanca (started in 1617), with its three-nave magnificent church, the free Doric interior of which, however, is baroque only in certain forms, stands already on the soil of the new time. Its façade also abounds in baroque forms. A semicircular niche with a statue of Loyola already has a real baroque refined frame and pediment with volutes. The triglyphs of the Doric entablature take the form of consoles. Cartouches with coats of arms are decorated with in-depth fields of lateral timpanas. According to Schubert, Juan Gometsu de Mora, in all probability, belongs to the above-mentioned Bernardine oval church in Alcala de Henares.

Fry Francisco Bautista, creator of the Jesuit Church of San Isidro el Real (1620-1651), took a step further in the development of independence of forms. According to the plan, it does not deviate from the rest of the single-nave Jesuit dome churches, which are transformed into three-nave ones only by empors above the rows of chapels. Its front side with two low towers on the sides seems to be single-storied thanks to the integral Doric system of columns and pilasters and at the same time three-storied thanks to three rows of windows connected in one piece by slightly baroque intertwining frames. A new, independently developed order of columns with a wreath of leaves under the Doric Ehina, dominant outside and inside this church, but already known in the lower parts of the facade of the aforementioned Jesuit church in Salamanca, is why Shubert thinks that Fry Francisco Bautista took part in its construction. The auditory holes at the corners of the frames are arbitrary; All these features are repeated then in the elegant church of San Juan, in Toledo, built by Bautista.

Fig. 128. Fry Francisco Bautista. Facade of the church of San Isidro el Real in Madrid. From photos of Laurent in Madrid

In the hands of Felipe Berreios, in 1666 the renowned famous architect of his country, the “thickening” of all ornaments, especially vegetal, which, as we know, was also a sign of Italian baroque, grew stronger and stronger. The luxurious front side of its single-nave, narrow, hall la Pasion church in Valladolid (1666–1672) with a dome over the choir not only reveals this “thickening” of all plant ornaments in cartouches, rosettes and garlands of fruits, but also transforms all planes, even the rods of columns and pilasters in the game of speakers and protruding geometric shapes in the spirit of the later “Hurririverism”. A similar abundance of jewelry flaunts the lower floor of the noble, despite all this pomp, double-tower facade of San Cayetano in Saragossa, in the upper part of which the baroque outrage is combined with stately simplicity. At the top and bottom of the Doric style, pilasters protrude from two adjacent pilasters, which is not often found in Spain.

In contrast, the painter Francisco de Guerrera Junior (El Motzo; 1622–1685), in his famous architectural structure, the second cathedral in Zaragossa, Nuestra Señora del Pilar (1677), tried to shine not so much with new forms of decorations as with its original layout of rooms. Since the four slender corner towers of the widely stretched building are only partly finished, and its outer walls are left without cutting, from the outside it gives the impression of only its eleven domes lined with bright red, green, yellow and blue tiles. The main dome rises above the main altar. Paired pilasters of powerful, in the middle of internal pillars jutting out like a niche, were redone anew in the style of later classicism. The graceful interior Baroque ornaments of Herrera have been preserved only in small numbers.

From the 17th to the 18th centuries, San Salvador, the large Jesuit parish and preaching church in Seville, built in 1660–1710, translates us. according to Jose Granado's plans. Against custom, this is a three-nave hall church, supported by fourteen pillars jutting out from the circumferential walls and decorated on three sides with Corinthian half-columns, and six free-standing pillars with the same ornaments on all four sides. Above the middle rises the dome. The half-columns are partly chilled, partly entwined with exquisite baroque ornaments. Above the ordinary niches stretches the specified protruding wall pilasters passage. The church belongs to the noblest buildings of Spain in the spirit of baroque.

Around the same time, the Jesuit Church Nuestra Señora de Belén, the last of the large Spanish longitudinal churches of the 17th century, was erected in Barcelona (1681–1729), a sample of the Northern Spanish halls with a semicircular choir and side rows of chapels. A peculiar impression is made by the passage between these chapels and the main pillars, over which the galleries of empors stretch. This is the motive of the two-story palace churches such as the Catholic palace church in Dresden, with the middle part, intended for preaching, and the side for the processions. If the interior of the temple is made in the Doric style, strictly stylish, but relatively simple, then the exterior is even more decorated with twisted columns, faceted pilasters and thickened frames.

Next to these rectangular buildings, octagonal, round and elliptical, funerary and collegiate churches developed in the middle of the 17th century. The main builder of the Pantheon, the octagonal dome burial chapel of the Spanish kings in the Escorial (1617) was Juan Bautista Crescetius (1585–1660), originally from Italy. Juan Gomez de Mora and others also participated in the construction. Internal wall architectonics consists of jasper with gilded bronze ornaments. High Corinthian capitals cap a pair of grooved pilasters. The vault and the eaves are filled with abundant plant ornaments. Statues of flying angels are placed in front of the wall pilasters. The language of forms reveals a timid transition to baroque.

Further development of the oval baroque churches is represented by the “de Nuestra Señora de los Dezemárados” chapel in Valencia (1652–1667) of the Martinez Ponce de Urranas. Attached to the rectangle, it is dissected outside Dorically, inside Ionic. The language of its forms is under Italian influence, which, naturally, was stronger in the coastal cities of the east than inside the peninsula. This “document of the Italian Baroque on Spanish soil” (Schubert) is the Jesuit College’s round church in Loyola (1689–1738), the birthplace of the founder of the Jesuit Order. The original project was executed by the great Italian architect Carlo Fontana. The performance was led by Ignazio de Ibero (born in 1648). The middle circle, over which the dome rises, is swept by a course like a side chapel, distant from it by eight pillars with Corinthian pilasters. The exterior, animated by paired semi-columns and pilasters, lined with slabs, with an arched portal above which a torn pediment rises, is decorated in the Hurrigwehr style downstairs quite simply, and on the frieze with prominent Corinthian capitals it is very luxurious.

The Segovia, Reus and Toledo Town Halls, which have already been mentioned above, were followed in 1644 by the alteration of an old palace into the Madrid City Hall, the work of the sculptor and architect Alonzo Carbonell, the successor of Juan Gomez de Mohr in the position of the main palace architect. Simple, with beautiful corner towers, the building is still strictly dissected. Its main portal in the style of high Baroque refers to the last time. The overlapping plates under the main eaves of the towers that appear here are hanging down in the manner of toothed leaves.

A little earlier, already in 1643, the “palace dungeon” of Juan Bautista Crescencio, now the Ministry of the Interior in Madrid, was completed: the brick building was sheathed with granite slabs framing the windows also straight, with four-sided, under light domes, side towers and a three-window front door on the pillars, which one discovers, as opposed to the calm importance of the whole, an invasion of baroque fantasy.

Crescencio and Carbonell were the main participants in the construction of the Buenretiro castle, which was completed in 1631. There were few survivors of it. This building also seemed to be distinguished by the dignity of the language of forms.

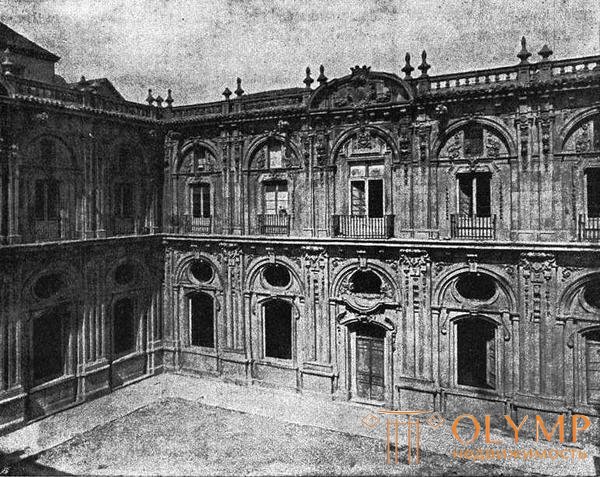

At the height of a peculiar pictorial Baroque style I stand once ridiculed, but attractive, by the painter José Jimenez Donozo (1628–1690) in 1652, the courtyard of the Santo Tomas College in Madrid, noble in its basic proportions and free in the elegance of pilasters’s ornaments, already resembling Baroque, but in any case independent of any kind of "orders of columns."

Fig. 129. Двор коллегии Санто Томас в Мадриде. По фотографии Лорана в Мадриде

Частные дворцы, имеющие художественное значение, в XVII столетии были редки в Испании. Не оскудевшая часть дворянства боялась зависти испанского двора. Только в захолустьях, например в Овиедо, в приморских городах, как Валенсия и Барселона, развилось нечто вроде художественною стиля жилищ, однако, в сильнейшей зависимости от Италии. В Овиедо дворец графа Нова постройки Мануэля Регверы, с его спокойно чередующимися плоско закругленными, плоскими и треугольными фронтонами над окнами, построен также в XVII столетии. Большинство замечательных дворцов Овиедо и все выдающиеся барочного стиля жилища Валенсии и Барселоны принадлежат уже XVIII столетию.

3. Стиль висячих пластинок

Особым самобытным течением в испанском барокко является стиль висячих пластинок — особенный способ украшения колонн, родственный мавританскому стилю. Данный стиль особенно сильно был развит в городах северо-западной Испании.

Здесь мы должны остановиться еще на особенном направлении испанского строительного искусства, о происхождении которого уже упоминалось выше, — направлении, превратившем стиль пластин с зубчиками листа в главный элемент декоративного стиля. Вместо пилястр встречаются часто только лизены, вместо капителей — вырезанные в форме языков, наложенные одна на другую пластины, предшественницы которых в Испании, кроме подобных же мавританских украшений, являются уже в некоторых орнаментах собора Хуана де Герреры в Вальядолиде. Полного развития они достигают уже на башнях ратуши в Мадриде. Известный живописец и скульптор Алонсо Кано из Гранады (1601–1667), как зодчий, взявший свой собственный путь, особенно любил этот род украшений. Кано связал с барочной свободой стиль висячих форм. Триумфальная арка, воздвигнутая им в 1641 г. на Прадо в Мадриде для въезда молодой королевы Марианны, привлекла к нему общее внимание как к декоратору-зодчему. Переселившись в 1651 г. в Гранаду, он нашел случай проявить себя в качестве такового.

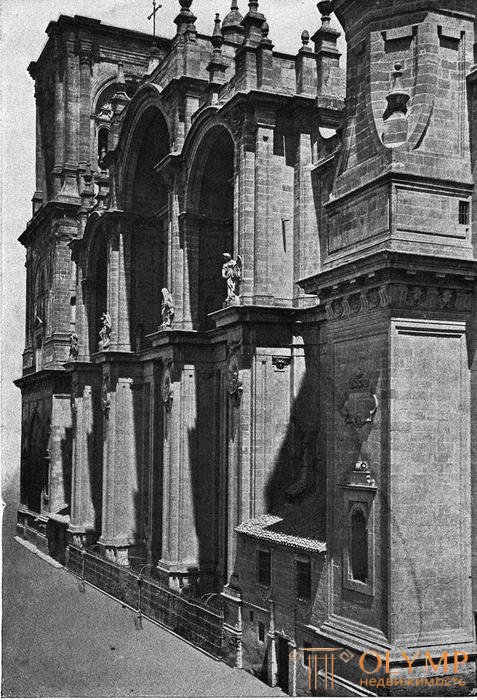

The facade of the Granada Cathedral, performed by Kano, is in fact a work of a new kind. It consists of three two-story arched niches, one next to the other, interlocking like a triumphal arch. The average niche is slightly higher than the side. Pilasters on the protruding pillars and on the rear walls are decorated with embossed extensions and medallions, foreshadowing the style of hanging plates. This style is fully developed in the church of Magdalen Kano in Granada, a noble hall and domed church with side chapels. Hanging plates of capitals, one on top of the other, “are used here with such a sequence as in no earlier building, namely as the main decorative motif that completely replaces the order of columns” (Schubert), and are decorated with light floral ornaments and cartouches. Outside, brick walls and tiled roofs are decorated with variegated glazed accents. Only the facade is made of hewn stones.

Fig. 130. Alonso Cano. The facade of the cathedral in Granada. From photos of Laurent in Madrid

How motifs of this art could be combined with motifs of old orders, with wreaths and new inventions of rich alabaster marble and stucco decorations, especially shows the interior of the burial chapel of San Isidoro in San Andres in Madrid, executed between 1657–1669. the student of Kano Sebastian de Gerrera Barnuevo (1619–1671).

The style of the hanging plates was especially consistently developed, perhaps without the help of Kano, flowing from the same sources in the far north-west of Spain, in Santiago de Compostela and in neighboring cities. Architect Domenigo Antonio de Andrade (died in 1712), creator of the grandiose baroque bell tower of the majestic cathedral in Santiago, filled in its upper parts with abundant Hurriger ornaments, from 1693 refused all plant ornaments in his Jesuit church of San Martin, now San Iorga, a proud three-nave basilica on poles in Coruna, turned to the style of the plates, which he connected to the strong ledges of the cornices and the deep, straight-cut ornamental fields of the walls and enriched them with curved outlines. It remains, however, in doubt whether this particular form of ornaments does not belong to the executive architect Domingo Maceira (1695). Further development, which led to the finished special style of the San Francisco Church in Santyago, was accomplished only in the 18th century.

Hurrigwerism, to which Schubert already attaches Kano's style, with its overloading of the building with semi-baroque, semi-exotic motifs of ornaments, as we see it on some of the above buildings, stands, strictly speaking, on different grounds. The creator of it, named after him, was José Hurrigvera from Salamanca (1650–1723), whose descendants and followers, who were partly the same with him, only developed this style to the “ultra-level” with fantastically complex decoration of planes only in the 18th century. The first works of Jose Hurrigvere, the tower and the sacristy of the cathedral in Salamanca, have already, especially in the phials, a new kind of mixture of Gothic and Baroque forms, heavy but not yet giving the impression of congestion. His hearse for Queen Marie-Louise de Bourbon (1689) turned out to be a major work for the new style developed by the master later, mainly in large carved and gilded altars: their twisted, richly decorated with plant ornaments the columns represent a heavy mix of many decorative features. . Samples can serve as his altars in San Esteban in Salamanca. The stone facades and portals, marked by the style of Hurrigvere himself, almost all died, and recently the luxurious facade of Santo Tomas in Madrid was also killed. Most clearly, he is as an architect in Salamanca’s town hall, the domed towers of which have never been completed. The heavily lush in general, the playful, arbitrary in some particular language, its forms are here essentially baroque in the sense of processing newer and more ancient forms. However, the town hall itself, however, already belongs entirely to the XVIII century, and the fact that the disciples and followers of Hurrigvere made of his still clearly distinguishable style can be traced only below.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)