1. General overview of the development of Spanish art

Spanish art in the 18th century developed under the strong influence of France and Italy. Nevertheless, it retained strong national features, especially in architecture.

Under the scepter of the Bourbons, who ruled Spain during the 18th century, the proud country of Sid increasingly lost its world political power, but she still continued to feel in the field of spiritual culture a great power and managed to keep herself also in art at a decent height. True, Spanish art could no longer boast of influence on other European countries, with the sole exception of Goya, a huge and now influential work of life, already on the threshold of the 19th century; within its own sphere of action, it skillfully flexibly adapts itself to the international currents of time, and sometimes even revives its old artistic original beginning again.

Spanish architecture completely preserved this national imprint. Hurrigiverism, this peculiar direction of the national Spanish baroque, already outlined by us, with an elaborate overload of ornamental forms, only now blossomed in its most bizarre manifestations; likewise, the “plate style”, which enriched or even supplanted the forms of ancient column orders, with sawn hanging forms, developed quite consistently only in the 18th century.

The prolific pupil of Hurrigvere Pedro Ribera gave in 1718 in his elegant church Nuestra Señora del Puerto in Madrid a sample of a free, picturesque style, but soon after 1722 he cluttered the main portal of the facade of the Provisio Provincial (Provincial House of Charity) in Madrid with a whole mass of fantastic intertwined particulars in the spirit of Hurrigvere.

Another pupil of Hurrigveri, Narciso Tome, executed the Baroque style in 1715, together with his brother Diego, the facade of the University in Valladolid, in an overly lush middle section, which seems to be a pretense, and then, as the architect of the Toledo Cathedral, is known for its huge, picturesque plastic construction "Trasparente", completed in 1732, behind the walls of the main altar turning into a light lantern erected above it, this "giant mosaic of selected marble varieties of bright colors” (Schubert), with columns, niches and stone curtains, with saints, angels and clouds. In the spirit of Hurrigvere, in the extraordinary abundance of capricious, but skillfully interconnected motifs, was also conceived in 1725 by Leonardo de Figveroa the middle ledge of the San Telmo palace in Seville, rebuilt only after 1775 by his grandson Antonio Matias de Figveroa. The most characteristic specimen of this anti-classical overload is the choral bypass of the Cathedral of Granada, designed by José de Bad in 1741 and made in 1793. Extreme limits were reached in this direction by architect Francisco Manuel Vazquez and sculptor Luis de Arevalo in the Carthusian monastery in Granada, built between 1727 and 1764 All the planes and surfaces of closely placed pilasters are covered here with broken and curved linear ornaments in sharp relief, apparently inspired by similar ancient Mexican or ancient Peruvian, and form here the rest of the soul-breaking combinations of Spanish hurriverism here in restless, disturbing spiritual world.

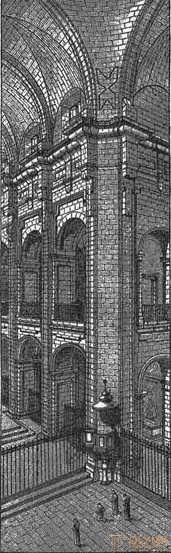

Fig. 221. Francisco Manuel Vazquez and Luis de Arevalo. Sacristy of the Cartesians in Granada

In Sant Jago de Compostela, the highly esteemed center of Catholic pilgrimage in the extreme north-west of the peninsula, where rich construction activity flourished again in the 18th century, hurriverism developed alongside the “slab” style with which it sometimes entered into union. The follower of Andrade Fernando Casas-i-Novoa (died in 1751) was the builder of the magnificent, begun in 1738 facade of the cathedral of this city, its richly decorative, topped with a high pediment, the middle part is furnished with two sharply dissected towers. The general character of this facade is Gothic, while the details are partly maintained in the spirit of strict Renaissance, and in part they represent the transition to the most intricate Hurrigrigism.

Fig. 222. The pillars of the church of San Francisco at Sant Jago de Compostela

Fig. 223. Casa del Cabildo in Sant Yago, built by Sarela

The most luxurious Spanish private building of the XVIII century - the house of the Marquis de Dos Aguas in Valencia. Gamemüller considers this house one of the few examples of exterior wall decorations in the style of French Rococo. The cuboid corner towers abound in its winding contours, and the portal and windows of the facade are richly framed in the Baroque style Hurrigvere. However, the French influence here can hardly be proved. This is Italian high baroque in the Spanish spirit.

Fig. 224. House of the Marquis de Dos Aguas in Valencia

We have already traced the constructions of the Italian Baroque in Spain to the beginning of the 18th century, having finished our consideration by the church of the Jesuit College in Loyola, designed by Carlo Fontana. The Bourbon kings of the 18th century gave a decisive preference to Italian architects, whose influence completely overcame national Spanish Hurrikverizm. His place was at the beginning of the Baroque style, painted with Vitruvian classicism, mainly in the new buildings of the royal castles in La Grana (near Segovia), in Madrid and Arangues. The most famous of the foreign architects who led these palace buildings was Filippo Yuvara who, in addition to his Italian buildings, built Ayuda Palace and Church of the Patriarchal in Lisbon when in 1734 he was called to Madrid. He was followed by Giacomo Bonavia (died in 1760) and Giovanni Battista Sacchetti (died in 1764), his own pupil of Yuvara.

The Palace of Ildefonso in La Granier, designed in its main parts by Teodoro Ardemans (1664–1726), is a picturesque two-story building, with a high roof and a facade decorated at the bottom with pilasters in the Doric, at the top in the Ionic spirit, and in the main parts with double pilasters — it seems more French than Spanish. The most false classical, in the sense of Palladio and Vitruvius, is the design of Yuvara, designed by Sacchetti, the middle building from the side of the garden, both floors of which are covered by one Corinthian order.

The Royal Castle dominating over the city, for which the project was completed in 1734 by Yuvara, built after Sacchetti’s somewhat modified plan after his death, is already more false classical and cold. A quadrangular, with four strong projections in the corners of the building contains a square courtyard surrounded by arcades on the pillars. Representing a single whole, dignified, the Corinthian on risalits, in other parts of the Doric order, covers the main floor and two mezzanines, above the high socle with socle plates.

Giacomo Bonavia, whose assistant, Alexandro González Velazquez (1719–1777), was famous as a decorative painter, took part in the construction of the new castle in Aranjuez. This widely spread building begun by building in 1728 looks quite dry.

The Spanish-Hispanic building, reflecting the transition from the Baroque Hurrigues to the Baroque of Vitruvius and from it to the classicism of Herrera, is the Cathedral of Cadix (1722–1838), the project of which belongs to Vicente Acero, the builder of the facade of the Cathedral in Malaga. The façade is very picturesquely decorated with two round towers, medium-sized, topped with a low pediment, the risalit of which is again deepened by a high, richly dissected entrance niche. The classical interior of this cathedral is the most harmonious and powerful creation of architecture that Spain has seen since the Middle Ages.

Fig. 225. Vicente Acero. Kadiks Cathedral

This prepared the way for the “Roman-Herrean classicism”. It is clear in itself that in Spain, not so much Palladio as Herrera enjoyed the reputation of a strict exemplary classic. The leader of Spanish architecture on this road was Ventura Rodriguez (1717–1785), the first professor of architecture at the Madrid Academy, founded in 1772.

The best work of baroque interior architecture is its church of sv. Mark (1753) in Madrid. The plan of its lower base consists of five intersecting ovals. The classical purity and strictness of the forms differ in the parts of the cathedral of Nuestra Señora del Pilar in Zaragoza, which were built with pilasters of Corinthian style, built in the same year. Ventura becomes a full classist in her ionizing, chastely strict Church of the Incarnation (Encarnacion; 1755–1767) in Madrid.

Of the students of Ventura, Francisco Sankhes (1737–1800) and his nephew Manuel Martin Rodriguez (1746–1823), who performed a number of significant buildings in Madrid, follow him most closely, while Agustín Sanz (1124–1801) shows in his cruciform, subtle designed, already reminiscent of the Louis XVI style parish church of Santa Cruz in Zaragoza, a new independent artistic taste.

This was followed by Juan de Villanueva (1739 to 1811), who in 1785 adorned the Prado Museum with an open Ionic portico. Its best structure, representing the transition to the "Greek Renaissance" of the beginning of the 19th century, was the Madrid Observatory with its six-column Corinthian portico and a round Ionic temple erected on the roof.

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)