Introduction Architecture

The German art of the mature Middle Ages is drawn against the rich paint background of a strong political and religious struggle. Epoch 1050–1250 It began under Henry III, who at his discretion appointed and succeeded the popes, the highest rise of the power of the German Empire, which, however, soon had to go to Canossa: the era of this era is all glorious, rich in large historical figures, shrouded in legend the reign of the House of Hohenstaufen - at home, which slowly but uncontrollably bled to death in the uninterrupted campaigns of the emperors belonging to it to the Far East, to the beautiful South and within the empire. This epoch, still surrounded by a brilliant halo, ended with the death of the great, passionately loving art of Emperor Frederick II, to soon be replaced by “sometimes without beginning, sometimes horror” (Schiller).

Against this background, painted in the colors of blood and iron, but animated by silver flowers and golden threads, the German art of the mature Middle Ages appears in calm grandeur. The production of this art was influenced by many conditions; Nevertheless, the international imprint on this art leaves no doubt as to the national creative power invested in it.

At Ottoman time, German education, although in Latin dress, still stood firmly on its own legs; but from the second half of the eleventh century, in many of its areas, it fell under the influence of its neighbors, French culture. The marriage of Henry III with Agnes Poitou contributed a lot to the penetration of French civilization into Germany. Then the Clunyans and later the Cistercians subjugated the religious life of Germany; even splendid German poetry developed under the influence of contemporary French poetry. “In the valleys of Provence, the songs of the Minnesingers were born,” said Uland. However, in German poetry of that time, upon its close study, the original German artistic power was visible. Such German creations as “The Song of the Nibelungs” and “Gudrun”, or such purely German songs as the songs of Walter von der Vogelweide, not to mention others, indicate that German medieval art, no matter how eager it went to school to the romances, it was very far from hiding the features of their national identity. The Romanesque art of Germany with all the fibers of its heart is German art.

With sufficient clarity, this is shown not only in poetry, but also in German architecture. The great traditions of Ottoman time, in which, as we have seen, the Romanesque art of Germany was taking shape, continued to operate for almost a century. The Romanesque churches that have survived in this country, having emerged in their present form in the era under consideration, have all those features in their highest and most consistent development that we used to call romance. Despite the fact that some of their main features were developed much earlier, in the remotest Christian East, and some architectural details were borrowed from the tribal Lombard south, these buildings, by their very special character, are German from basement to tower spire. Only during the XII century, when in France (see fig. 167) did the Gothic style gradually develop organically, did the Romanesque architecture of Germany begin to perceive those new forms, which are what the cross vault with ribs, the pointed arch and the system of buttresses are quickly in France merged into one new whole. Gothic entered into use in Germany only at the beginning of the subsequent period, that is, around the middle of the XIII century. Thus, between the Romanesque and Gothic styles in Germany there was really a transitional style. The fact that this style, as Dégio rightly observed, was more original and active in France, and imitative and passive in Germany, is explained by the very essence of its evolution in these two countries. But the German transitional style applied alien architectural forms so skillfully and with such taste that it created works full of charming artistic charms.

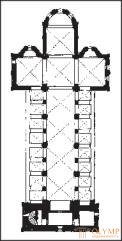

Fig. 183. Plan Brunswick Cathedral. According to Goes

Fig. 184. Romanesque arc frieze. From drawing

Fig. 185. German-Romanesque column With a picture

Most of the ornamental forms of the German-Romanesque style we have already met in Lombard art, many of these forms in equals, and some even in ancient Syrian art. The outer walls were partitioned in the vertical direction by means of paddles protruding from the wall surface, occasionally turning into buttresses, and fake arches covering groups of windows and then continuing on the walls, in the horizontal direction by means of arcature friezes (fig. 184) and small ones stretching under the eaves circular-arched galleries resting on columns. Frames and protrusions of entrance doors even during the whole XI century are distinguished by simplicity. Only in the twelfth century did gradually spread in Germany, penetrating from Burgundy, more luxurious forms of portals, with oblique and forming rectangular ledges with side walls, decorated with columns, semicircular rollers and, finally, figures, and with archolts decorated with the inner surfaces of arches.

Fig. 186. German-Romanesque base of the column, equipped with corner sheets. Lubka

In the interior, predominantly shaped columns and highly elongated, attached to the pillars and walls of the semi-columns serving as supports for the arches are noteworthy. Rods of German-Roman columns, mostly carved from one stone, usually taper upward, like ancient columns, but only in the transitional period are decorated with rings in the middle. Their base is an ancient Attic base, consisting of two shafts and a fillet between them (Fig. 185). This base, initially too high and steep, in the heyday of the Romanesque style, gets again almost classical proportions and then, having become elastic and flexible, varies in a very whimsical way. The space between the rectangular ground and the lower shaft of the base is filled with a sculptural decoration, sometimes taking the form of an animal or the animal's head, and later mostly the shape of a beautifully curved sheet - the so-called neck or corner leaf (Fig. 186). As for capitals, the Carolingian imitating Corinthian captain with the motif of the acanthus, is becoming more and more rare.

Around 1050, that is, precisely at the time from which we begin our review of German-Romanesque art, “in Germany,” as Degio put it, “ancient memories are fading everywhere”. Separate exceptions only confirm this truth. The medieval deciduous cupped caps, of the varieties of which the ornamented motifs of deciduous buds used in particular love, belongs in Germany to a number of borrowed forms taken in transitional style from France. At the height of the Romanesque era, cuboid capital dominates German architecture. Although it is possible that this capital appeared in Lombardy earlier than in Germany, where, however, we met her already in the church built by Bernward. Michael in Hildesheim (see. Fig. 94), but in no other country, it is not so widespread as in Germany. Cube-shaped at the top and hemispherical at the bottom in its own half, it is perfectly adapted to serve as an intermediary link between the quadrangular abacus and the round stem of the column (fig. 187). Being available for various changes in details, a cuboid capital represents surfaces suitable for plastic and pictorial ornamentation; these surfaces are decorated with elements of ancient geometric ornamentation, now with human and animal figures, or with stylized vegetative motifs, still drawn from the treasury of ancient forms.

Fig. 187. German-romance cubic skewed capital. From drawing

Finally, in Germany it is easy to trace the role that polychromy played in the Romanesque architecture. The fact that the ceilings and interior wall surfaces were usually assumed to be painted from the very beginning is quite convincingly proved by the Romanesque wall paintings and ceilings preserved in Germany. The columns with their bases and capitals, the sculptures that adorned the interiors of the churches, the arches and their supports also shone with colors, as clearly shown by the surviving traces of the latter; but in places where colored rocks were used, as, for example, in the Hildesheim church of Sv. Michael (Michaelskirche), reminiscent in this respect of the Florentine church of San Miniato and the Cathedral of Pisa, one must see exceptions to the general rule; such exceptions, it may be thought, were more than they thought. Outside, only portals and sculptures were painted. In the Romanesque period, the transition from polychrome architecture (and plastic) to monochrome had not yet taken place, but it could already be prepared in some places.

We begin our review of the works of Romanesque architecture in Germany directly adjacent to the Ottoman architecture, from the Old Saxon countries, including Westphalia on the one hand, and Thuringia and Saxony on the other.

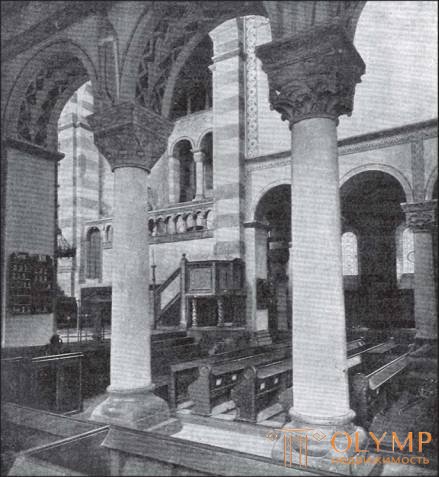

The flat-covered basilicas with two choirs in these localities are preserved in exemplary structures. As an example, we note the church of St.. Michael in Hildesheim. The building of Bernward burned down in 1034, and the present church was consecrated in 1186. The plan of this church with transepts remained the same; Probably, its architecture has not undergone significant changes either. The supports of the longitudinal hull alternate in such a way (Fig. 188), that each pillar is followed by two columns with attic bases, which are provided with corner sheets, and with ornate cubical capitals. The transepts are spacious, very picturesque empores. The strongly elongated western choir has outside a circle that does not belong to the church itself, resembling the plan of the church of St. Gallen abbey (see fig. 89). The Eastern choir, solemnly gloomy and also very long, started with construction in the 12th century; on the continuation of the small naves it is equipped with lateral absides. The whole building, topped with six towers, is distinguished by the luxury of its interior decoration and the nobility of proportions. The lining of many wall surfaces, both inside and outside in rows of red and white stone, gives this church a spectacular coloring, which is not always achieved through painting.

Fig. 188. The interior of the church of sv. Michael in Hildesheim. From a photo of Nöring

The correct alternation of pillars and columns is assimilated in Saxony by many, mostly small churches. The first example of this kind of church was the church in Gernrode (see figs 93 and 95); it was followed by the church in Gocklingen (about 1117–1170). Here the bases of the columns are already equipped with vultures, the building is decorated with arcature friezes and shoulder blades and there are three eastern apses: one apse of the choir and one apse on the wings of the transept. Basilicas with only one pillar are rare in Saxony. If they meet somewhere in it, this indicates the connection of their builders with Swabia, in which such churches prevailed. Of the buildings of this type, it is necessary to point out the magnificent Hammerslebensky Cathedral with its eastern towers, three absids at the ends of three naves of the same length and columns richly decorated with sculpture. Among the most magnificent Romanesque church buildings in Germany, probably belonged to the ruined, but still charming Benedictine church in Paulinzell (1105–1119) - the flat-covered column basilica, of the five eastern apses of which two are on the branches of the transept, while its western end was subsequently added (1163–1195) luxury porch, lined with pillars. In the old Saxony there are also basilicas exclusively with pillars. These churches provide an opportunity to trace how the shape of the pillar changed in the Romanesque style. We find simple tetrahedral pillars, for example, in the Bremen Cathedral (circa 1050), in the Church of Our Lady in Halberstadt (1135–1146) and in the beautiful (pledged also in 1135) Church of Königslutter, whose choir and transept, with their circular -arcoded, devoid of ribs, cross vaults, already represent the transition to the device of vaulted basil. A more developed and elegant form of pillars with beveled corners (as in Gernrode; fig. 189, b) or with corner columns (as in Häcklingen; see fig. 189, a) we find in the church of Vekselburgsky castle famous for its sculptures (1174–1184 ), which had originally a flat wooden ceiling, and in the Cistercian church in Burgelin, near Jena (1133– 1199), the remains of which are one of the most picturesque ruins in Germany.

Fig. 189. Capitals of the pillars: a - in the church of Goecklingen; b - in the church of Gernrode. From drawing

Basilica with pillars prevailed in Westphalia, where only in some small churches a pair of slender columns alternate with pillars. This passion of Westphalian church architecture for the pillar basil is associated with vaulted experiences made in Westphalia earlier than in the eastern parts of old Saxony. A typical feature of the internal architecture of the Westphalian Romanesque churches is their hall form (three naves of the same height), which has become common in them since the construction of the aforementioned small chapel of St. Bartholomew in Paderborn. These churches are characterized by severe, topped with one tower, western facades. Падерборнский собор представляет собой крестообразную церковь зальной системы, с прямо срезанным хором и массивной четырехгранной башней; Минденский собор — такая же крестообразная церковь зальной системы, с готическим хором и романской западной башней. Cathedral of sv. Патрокла в Зёсте первоначально был базиликой со столбами; его западный фасад с красивой башней и сводчатой галереей вровень с землей напоминает скорее ратушу, чем церковь.

Наконец, из сводчатых базилик связного плана со столбами самая замечательная в Саксонии — Брауншвейгский собор (1173–1194), который, несмотря на некоторые позднейшие готические добавления, в том виде, как он был освящен в 1227 г., представляет романский стиль во всей его чистоте. Все части этого собора строго соразмерны и составляют одно гармоничное целое. Над нерасчлененным западным фасадом поднимаются две восьмигранные башни. Собор интересен своей богатой, хорошо сохранившейся росписью.

Led to the transitional style in Saxony. Saxon constructions of this style are romance in terms of just because they are But there is a pointed arch, and The semi-columns of the pillars, often encircled in the middle of the ring, give the cubic capital a way to a cup-shaped, decorated with leaves.

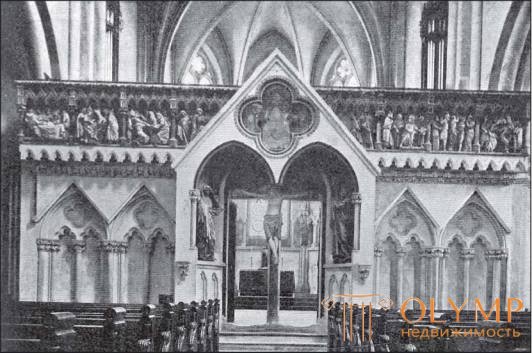

Fig. 190. The interior of Naumburg Cathedral. From the photo of Konig

In the development of the transitional style also in Germany, especially in the Saxon lands, an important part was taken by the Cistercians. They introduced a direct ending of the choir, a simple vaulted covering, in which the lancet arch became early to be used, and wall brackets as supports for service columns; they abolished the towers, completely removed from the Cistercian church architecture from 1157. The oldest Cistercian building in Germany was the church in Altenkamp, near Cologne, erected in 12112 and equipped with eastern towers, which at that time had not yet been banned. But soon after that rather characteristic Cistercian churches appear in Old Saxon places. Examples of buildings of this kind can serve as monastic churches in Marienthal, near Helmstadt, in Marienfeld and Lokkum, in Westphalia. But the most interesting Cistercian church of ancient Saxony is located in Riddagsgausen, near Brunswick. It is especially original straight cut choir, surrounded by a lower, compared with him, bypassing with the crown of even lower quadrangle chapels. It is impossible, however, to say that this transition of the old French roundabout, with its chapels located along radii, into a quadrangular form, produced a particularly pleasant impression on the viewer.

In Saxony, as well as in other German countries, there is no shortage of monuments of civil architecture belonging to the time in question, especially in residential buildings. Essenwein, Alvin Schultz, Piper and Simon wrote about them. The forms developed by church architecture were transferred by princes, knights and townspeople to the architecture of their palaces, castles, town halls and private houses, and this development of civil architecture often went along with the church and led to original tumors. The remains of the civilian buildings of the Romanesque era in Saxony, where residential houses were still made of wood at that time, are rare. You can, however, point to the town pharmacy in Saalfeld as a charming Romanesque stone building of this time. But ancient Saxony is rich in ruins of knightly and princely castles. Consideration of knightly fortified castles, we provide researchers, specialists, but we can not ignore the imperial palaces and princely castles. The most ancient and majestic of them is the imperial palace in Goslar, begun by building under Henry II and expanded by Henry III around 1046; however, the preserved building, renewed and decorated anew in the XIX century, appeared, perhaps, only in the middle of the XII century. The lower floor is occupied by low rooms with a boxed vaults. The upper floor consists of spacious rooms with flat ceilings. On its front side there are seven triple circular-arched windows. The middle is occupied by a huge main window, divided into parts in a horizontal direction; on both sides of it there are three closely adjacent one to another triple circular-arched windows. At the height of the second floor, on the side, a terrace was attached, on which are wide open stairs. The palace of Heinrich Leo in Braunschweig is richer decorated. This massive and at the same time elegant building of a hall system, belonging approximately 1166–1172, erected on the site of the old Guelph castle Dankvarderode, suffered much from the enemy invasions and was restored in the XIX century, and restored not only the main hall, but also living rooms and connecting galleries between the castle and the cathedral south of it; The tower lying in the ruins probably belonged to the two-story chapel of the castle. The square of the Braunschweig Castle, in the middle of which there is a bronze lion, still carries us right into the flourishing period of the German-Roman style. Of particular note is the Wartburg castle, near Eisenach, which is picturesquely situated at a considerable height and surrounded by forest, is the residence of the Thuringian landgraves. It was founded in 1067 by Ludwig Skakun and expanded in a century by Ludwig III. In the present luxuriously restored castle the old is mixed with the new. The main hall is on the third floor. The wealth of fantasy and purity of work characteristic of Saxon bricklayers is manifested completely not only in the general architectonics of this building, but also in many of its individual forms, such as, for example, capitals in the form of fantastic animals of some of the hall and window columns arranged in beautiful groups, singly or in pairs. Of the two-story castle chapels of the Romanesque era, the most luxurious and beautiful is in Freiburg an der Unstrut. Its lower floor is still Romanesque, and the upper one is built in a very graceful transitional style; Four slender, free-standing columns surrounding the central pillar are connected by spring arches with four semi-columns set at the corners. These arches are lined with battlements, which we are entitled to include among the motives borrowed from Arabic architecture in the era of the Crusades. "The ribs of the cross-vaults," said Lotz, "with their combination form a hanging flower, as it were."

In the Romanesque residential buildings of old Saxony, we find almost all the individual motifs found in German church and civil architecture. In some places a three-blade arch in the form of a clover leaf joins the semicircular arch; simple columns in galleries and on the sides of windows are sometimes doubled, and they are placed either side by side or (as in Wartburg) one behind the other. The usual cubical capital in some cases gives way to a deciduous capital, developing as a new Romanesque form, based on the ancient Corinthian capital. In the ornamentation, along with the ancient braided pattern, the Mycenaean vegetative curl stylized in the Romanesque style (see v. 1, fig. 209), alternated with half-palmettes and leaves, continues to be found. Rarely in the Saxon-Romanesque style there is a zigzag, belonging, however, to the number of those motifs that the people and each epoch invent by themselves.

The sculptures performed in Ottoman time in Hildesheim under Bishop Bernward are presented in the light of world history of art by late autumn, semi-barbaric followers of Greco-Roman art. The appearance of these sculptures on German soil makes a great honor to the artistic sense of the German hierarchs of that time, but it did not entail further organic development. Following the late autumn of antiquity in the history of German plastics, winter inevitably began, which lasted until they began to break new, spring sprouts on local soil and at the same time did not breathe spring air from France.

The German plastic art of the 12th century, which cannot be compared with its French sister, is still poor in outstanding monumental works: its successes begin only in the 13th century. But in Germany in greater numbers than in France, stone and bronze church doors, tall wooden crucifixes and, finally, small metal products survived from the entire Romanesque era.

Fig. 191. Christ. Relief on the balustrade of the western empor monastery church in Gröningen, near Halberstadt. According to goldschmidt

The history of medieval German plastics, the study of which thanks to the works of Shnaz, Lyubka, Bode, Shmarsov, Goldschmidt, Vogt, Gazak, Clemen, and B. Riel has made significant progress, presents many interesting facts and interesting stages of development.

The second half of the 11th century in both Upper and Lower Saxony is far from the best period for sculptors. The last echo of the Ottonian century is in front of us a bas-relief portrait of King Rudolf Schwabsky (died in 1080) on a bronze tombstone in the Merseburg cathedral, executed purely but tough. A later work in style is the bronze chandelier of Bishop Gezilo (died in 1079) in Hildesheim Cathedral, the oldest and largest of the chandeliers, the general shape of which is heavenly Jerusalem: its rim is a jagged wall; the teeth are shaped like turrets like canopies, on which figures of saints stand.

The development of Saxon sculpture (1100–1220) Goldschmidt traced through three stylistic phases. The first phase, which lasts until about 1190, is characterized by a very obvious decline. Figures and groups of figures seem constrained, heads sculpted rigidly, lifeless; plastic modeling of folds of clothing and individual forms of the face and hands is replaced only by scratched contours; the movements are angular, schematic, there is no hint of expression. Some works of monumental plastics inside the Old Saxon churches belong to this stage of development, such as, for example, in the narthex (which is the only one preserved) of the Goslar Cathedral sculpted from knocking figures of the emperor and empress, the Mother of God and the three saints; in the south side nave of the church of sv. Michael in Hildesheim in the triangular spaces between the arches - sculpted images of nine highly elongated female figures, personifying themselves, as is evident from the inscriptions on the "wrappers", the commandments of bliss; on the balustrade of the western empor of the monastery church in Gröningen, near Halberstadt, Christ on the rainbow (fig. 191) and the twelve apostles, whose figures are already conceived more plastic, but are still very dryly executed. From the gravestone sculptures here are the three oldest monuments to the abbess in the Quedlinburg church; These monuments are similar in execution to the somewhat more mature bronze gravestone of Archbishop Friedrich of Witten (died 1115) in the Magdeburg Cathedral, which was previously considered a monument to the bishop of Gizelsky who lived a century later with the same name. Of the other Saxon cast bronze products, those cast between 1152 and 1156 belong to the same stage of development. in the Magdeburg foundry bronze boards that lined the so-called Korsun gates of St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod. More successful than their figure-rich images of biblical and mythological scenes, the individual figures of saints, of which one, the figure of a bishop, very closely resembles the above-mentioned figure of the Bishop of Witten Frederick on his monument in Magdeburg. Somewhat calmer and clearer is the composition of eighteen bronze reliefs with scenes from the life of St.. Adalbert on the doors of the Gneza Cathedral. The best of the Saxon cast bronze round sculptures is a bronze lion with an open mouth, set up by Henry the Lion in 1166 on the square of the Braunschweig Castle as a sign of the sovereign domination. The forms of this lion are heavy and tough; the mane consists of scaly strands, resembling the rudiments of art in the far East; nevertheless, against the background of the old buildings that surround this statue, it makes an impressive impression.

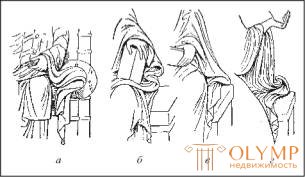

Fig. 192. Motives draperies: a - one of the Byzantine bone reliefs; bg - figures on the fences of the choir in the Church of Our Lady in Halberstadt. According to goldschmidt

From about 1190, new trends appear in German sculpture. It becomes noticeable desire for truth and freedom, to greater vitality and plastic roundness. Individuals become more characteristic and expressive, figures more rounded, noble and mobile; deeper embedded folds of clothes are more boldly made wavy and lively. That these individual features of greater freedom are observed in small works of Byzantine plastics, ascending, in turn, to ancient models, Goldschmidt proved by comparing drapery motifs in Byzantine bone reliefs with similar motifs on the choir fences in the Church of Our Lady of Halberstadt (Fig. 192). But this comparison also proves that the Saxon plastic in the second Romanesque phase of its development (1190–1210) sought, through greater relief and greater mobility, to express its own artistic feeling, and borrowing Byzantine motifs - subjected them to independent processing.

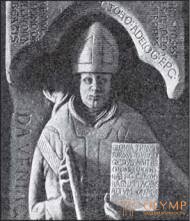

Fig. 193. A gravestone on the grave of Bishop Adelog in the crypt of Hildesheim Cathedral. According to goldschmidt

Что бы оставить комментарий войдите

Комментарии (0)